JAMES KYNGE

Back in 2014, US political scientist Francis Fukuyama described an ideal of “getting to Denmark”. Denmark denoted not so much a place, he said, but a symbol that all countries may aspire to. Liberal, democratic, peaceful, prosperous and uncorrupt.

Since then the world has hurtled in the opposite direction.

Americans have become profoundly sceptical about their democracy. Europe, rocked by Brexit, faces an assertive Russia. A “democratic decline”, as measured by US advocacy group Freedom House, was evident last year in countries where nearly 75 per cent of the world’s population lives.

China, with its confluence of authoritarianism and effectiveness, embodies an alternative reality. While the west was losing its way on the road to Denmark, China was getting to Dongguan, a city in the Pearl River delta that stands as a symbol of world-leading high-tech manufacturing.

In Beijing last month, the Chinese Communist party passed a resolution that paves the way for Xi Jinping, the leader, to stay in office until at least 2028, perhaps longer. Xi’s leadership was described as “the key to the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation”, a mission he has pledged will be realised by 2049.

This move sets up a vision utterly at odds with the post-cold war triumphalism of the west. Viewed from 2021, George W Bush could not have been more misguided when in 2002 he declared, “the great struggles of the 20th century between liberty and totalitarianism ended with a decisive victory for the forces of freedom and a single model for national success”

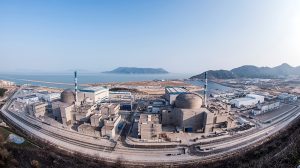

. An opposite scenario is now unfolding. China under Xi is centralising authority, limiting freedoms in the mainland and Hong Kong, running concentration camps in Xinjiang, bolstering the country’s nuclear arsenal, threatening Taiwan and reducing free market ties with the US.

And yet, according to the IMF, China will dominate the global economy by contributing more than one-fifth of the total increase in the world’s gross domestic product each year until the end of 2026. In addition, China has over the past four decades lifted some 770m people out of poverty.

Responding to such success, some in the west predicted China’s collapse. Others saw fatal flaws in its anti-democratic design. Many have questioned the sustainability of its debt-fuelled and resource-heavy economic model. Criticism of Beijing’s human rights record has been unrelenting.

But Beijing’s enduring effectiveness demands an understanding of the country on its own terms. Examining the patterns of the Chinese past helps to explain both the resilience of the regime and why there are questions about the direction in which Xi is taking the CCP.

Wang Yuhua, associate professor of government at Harvard, has parsed the characteristics of 49 dynasties that ruled China over some 2,000 years. He shows that the greatest threat facing emperors down the ages was not internal strife or foreign wars but the elite families populating the imperial court.

Some 76 emperors — more than a quarter of the total 282 since 211 BCE — were toppled, murdered or forced to commit suicide by these elites.

So it was crucial for Chinese rulers down the ages to find a way to control and placate the elites. But therein lay a “sovereign’s dilemma”, Wang says. The capacity of the dynasty to get things done depended on enlisting the their support. But when such families grew strong, they could — and often did — turn against the emperor.

“In order to maintain their grip on power, Chinese emperors broke the social ties among the elites, which rendered them an incoherent group,” he says. Such a course of action could extend an emperor’s rule and prolong a dynasty — but it also gradually weakened the capacity of the state to get things done. Wang sees parallels with Xi’s China today.

Xi’s anti-corruption campaign, which has targeted hundreds of senior officials since its launch in 2012, has helped limit the influence of the powerful “red families” that surround the CCP court.

As Xi waits to be anointed as latter-day emperor at the 20th National Congress of the Chinese Communist party next year, he must strike an age-old balance. It will not be Sino-US relations, climate change or even domestic economic growth that weighs heaviest on his mind.

His main priority will be to keep Chinese political elites sweet enough to maintain their support but disunited enough to enfeeble their resistance. It is all a long way from Denmark.

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/mco/4HRDOK4MF5DTNI55KREYIRNAKU.jpg)