Josephine Wolff

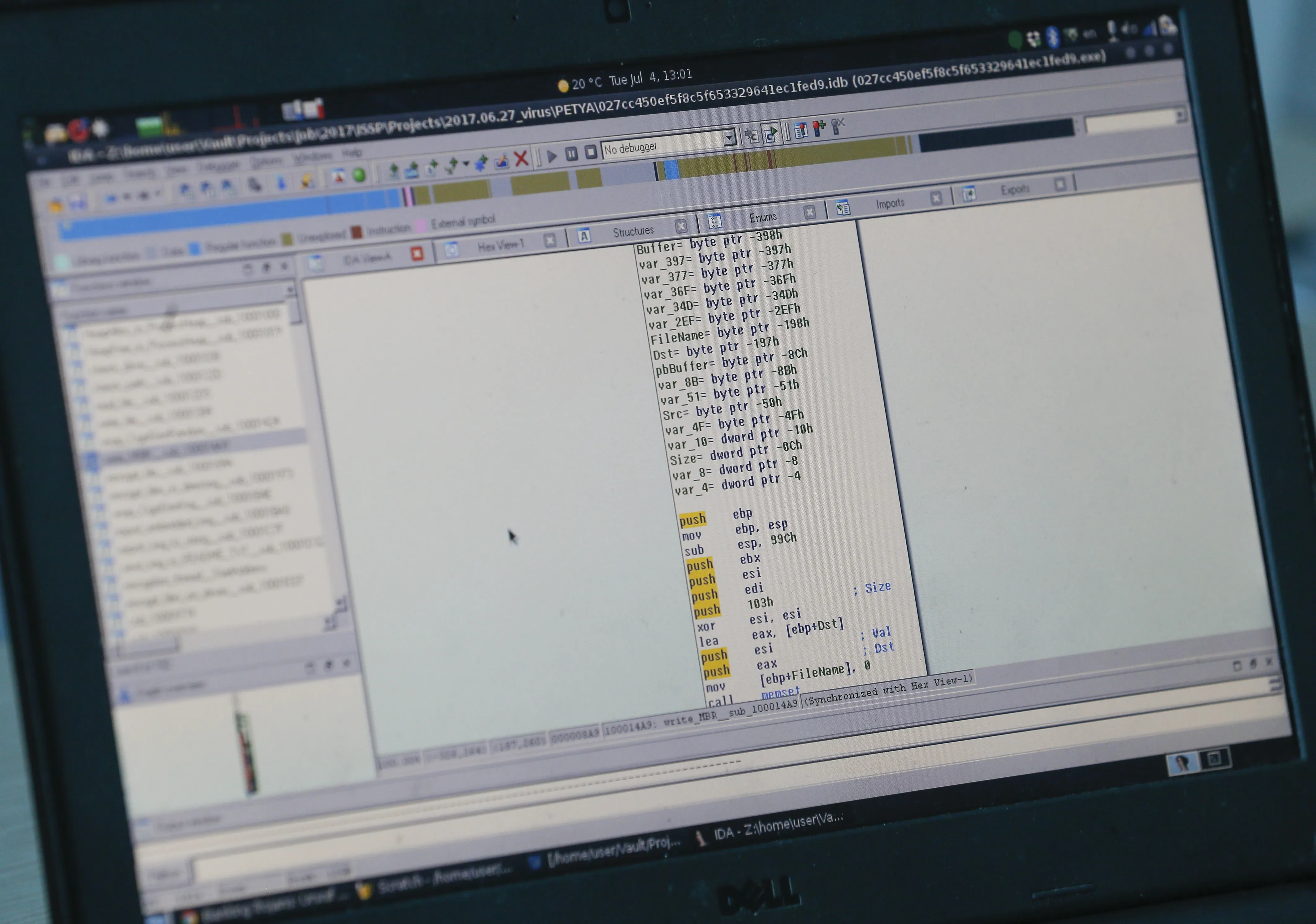

In June 2017, when the NotPetya malware first popped up on computers across the world, it didn’t take long for authorities in Ukraine, where the infections began, to blame Russia for the devastating cyberattack that would go on to do $10 billion of damage globally. NotPetya was a component of the ongoing conflict between Russia and Ukraine, but even though it was designed to infiltrate computer systems via a popular piece of Ukrainian accounting software, the virus spread far beyond the borders of Ukraine, causing an incredible amount and variety of damage.

One of the most consequential and as-yet-unresolved legacies of NotPetya centers on Mondelez International, the multinational food company headquartered in Chicago that makes Oreos and Triscuits, among other beloved snack foods. NotPetya infected the computer systems of Mondelez, disrupting the company’s email systems, file access, and logistics for weeks. After the dust settled on the attack, Mondelez filed an insurance claim for damages, which was promptly denied on the basis that the insurer doesn’t cover damages caused by war. The ensuing dispute threatens to not only remake the insurance landscape, but also has major implications for what companies increasingly at risk of being hacked can expect from their insurer.

Cookies under attack

Mondelez couldn’t have less to do with the tensions between Russia and Ukraine, but the company’s computer systems were still affected by NotPetya as it spread around the world. For Mondelez, the total damages were estimated at more than $100 million. So Mondelez filed a claim for the costs with its insurer, Zurich—only to then have that claim denied on the grounds that NotPetya was a warlike action and therefore excluded from Mondelez’s property and casualty insurance coverage. The ensuing lawsuit between Mondelez and Zurich over whether NotPetya was actually sufficiently “warlike” to trigger the exception in Mondelez’s policy will have far-reaching consequences for both buyers and sellers of cyber insurance policies. While the case remains undecided, insurance carriers and policyholders alike remain in a state of some uncertainty about what types of cyberattacks their coverage does and does not apply to, and policymakers have been slow to provide help to either side by, for instance, defining what types of assistance they might be willing to provide or what they expect from insurers by way of clarification.

Because it caused so much damage and was driven by broader political motivations, NotPetya is one of the most closely studied cyberattacks in history. Andy Greenberg at Wired, for example, has explored the malware in terrific detail, so when he declared in August of 2018 that “the release of NotPetya was an act of cyberwar by almost any definition,” it encapsulated the thinking of insurers like Zurich. Just two months earlier it had denied Mondelez’s claim for $100 million in NotPetya-related damages under its Zurich all-risk property insurance policy, pointing to the warlike nature of NotPetya. The June 1, 2018, letter to Mondelez denying their claim pointed to Exclusion B.2(a) in the company’s policy that specifically excluded coverage for any losses or damages resulting from “hostile or warlike action in time of peace or war, including action in hindering, combating or defending against an actual, impending or expected attack by any … government or sovereign power.” Cyberwar, the company argued, didn’t fall under the purview of its property insurance policies.

But was NotPetya really warlike? It was certainly perpetrated by a government, but that alone may not be enough to qualify it as an act of war. By the time Zurich issued its claim denial, several governments, including the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia, had issued coordinated statements in February 2018 attributing NotPetya to the Russian government. It was perhaps the most extensively and authoritatively attributed cyberattack ever, especially in the context of breaches which often give rise to disagreements about attribution and how definitively it can be performed. But many cyber intrusions and breaches are perpetrated by governments, and if all of those are viewed as being beyond the purview of cyber insurance coverage then cyber insurance could become largely useless for many policyholders dealing with a wide range of incidents from espionage to ransomware.

That’s why the decision in the Mondelez case is so crucially important—for both insurers and their customers. If Mondelez wins that means insurers will either have to cover a much broader range of cyberattacks or rewrite their coverage to exclude new categories of damages that go beyond warlike actions. On the other hand, if Zurich wins the case then policyholders may decide that there’s little point in purchasing cyber insurance, forcing insurers to craft new language for their policies to reassure customers that at least some government-sponsored cyberattacks will still be covered.

The future of cyberinsurance

Major insurers are already reshaping the language in their policies to prepare for the consequences of victory for either side of the dispute between Mondelez and Zurich . For instance, research by Daniel Woods and Jessica Weinkle has shown that insurers are increasingly building into their policies coverage for “cyber terrorism,” while still excluding hostile or warlike actions. The cyber terrorism coverage inclusion is presumably intended to reassure policyholders that they will be able to file claims for government-sponsored massive cyberattacks, despite the war exclusions in their policies. But the definitions of war and cyberterrorism are so ambiguous—and in many cases so overlapping—that it’s hard to see how this development does anything other than pave the way for more long legal battles like the one between Mondelez and Zurich.

Policymakers in several states and countries have taken an active interest in cyber insurance in the years since Mondelez’s suit against Zurich was filed, but they have done little to resolve the persistent uncertainty over what types of cyberattacks fall under insurance policy war exclusions. Nor have they helped clarify the extent to which existing government insurance backstops for terrorism, as laid out in the Terrorism Risk Insurance Act (TRIA) passed after the attacks of Sept. 11, might apply to cyberattacks like NotPetya, though the Treasury Department has begun soliciting feedback on how to do that. These clarifications might not resolve all of the ambiguity in existing cyber insurance policy language, but they could serve as an important first step in framing how the government defines cyber terrorism and cyber war. Those definitions would give insurers a clearer template to work from in writing their own policies and also provide policyholders with some language to compare their coverage against. Ideally, assuming the government is able to carve out a subset of cyberattacks covered under TRIA, that would also provide a clear boundary where private insurance coverage should apply: namely in all the circumstances where government coverage does not.

Regulators can do more than provide clearer definitions of cyber war and cyber terrorism; they can also help by being more careful in the way they talk about cyberattacks more generally to help avoid fueling similar legal disputes. When Senator Dick Durbin referred last year to the SolarWinds cyber espionage campaign as “virtually a declaration of war,” this is precisely the kind of quote that insurers and their lawyers seize on in lawsuits over whether or not incidents like Pearl Harbor or airplane hijackings that occur outside the timeframe of formal, legal war declarations can be considered warlike actions for insurance purposes. The results of those older legal disputes over insurance war exclusions can still be seen in the language built into policies like Mondelez’s today. The explicit designation in the Zurich policy of excluding any “hostile or warlike action in time of peace or war,” for instance, reflects changes made to insurance policies following Pearl Harbor, when some insurers denied life insurance claims on the basis that those who died at Pearl Harbor died due to an act of war. The families of those soldiers then challenged those claim denials on the grounds that the United States did not officially declare war on Japan until the day after Pearl Harbor. Accordingly, insurers began to expand their war exclusions to cover events that happened “in time of peace or war” so that they would not be restricted to only excluding events within the confines of official, legal declarations of war.

NotPetya, like Pearl Harbor before it, is already changing the ways that insurance exclusions are being written. But this time insurers are faced with the conflicting goals of trying to get themselves off the hook for coverage of catastrophic cyberattacks while still persuading their customers that most intrusions and breaches will still be covered. These conflicting pressures have led to even more confusing—and at times contradictory—language being inserted into cyber insurance policies in ways that do little to resolve any of the important and pressing issues raised by the Mondelez case. If policymakers are still hopeful that insurance will play a crucial role in helping organizations manage cyber risk, they should be actively engaging with carriers over how to establish clearer, better founded definitions of which types of cyberattacks should be covered by insurers, which types by government backstop programs, and which ones by the victims themselves.

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/mco/T6VRYEMYGVEPPKXF2PXHIMWJAM.jpg)