Shelly Kittleson

Iraq’s Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) were once heroes to some of the country’s Shiites. That was in 2017, when the PMF—with Iranian backing—helped end the Islamic State’s reign of terror through large parts of the country. Those victories on the battlefield, however, didn’t translate into success at the ballot box this month. The initial results of Iraq’s fifth parliamentary election since 2003 show Iran-backed groups, loosely represented by the Fatah Alliance, losing 28 of the 48 seats they previously held.

A political party backed by a designated terrorist organization in the northern Kurdish region of Iraq also fared poorly. The Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) had the firm support of the mainly Turkish Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), which the United States, the European Union, and Turkey have designated a terrorist group. The PUK’s rival, the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), emerged the clear victor in the voting: It won 32 seats, twice the PUK’s 16 seats. In the 2018 elections, the KDP won 25 seats and the PUK won 18 seats.

Somewhat predictably, the election’s losing parties have alleged voter fraud. “We do not accept these fabricated results, whatever the cost,” said a statement released by the office of Hadi al-Amiri, leader of the Fatah Alliance. “And we will defend the votes of our candidates and voters with full force.” Sometimes, such allegations were coupled with more specific threats of violence, such as one muqawama (“resistance”) linked commentator remarking during a televised interview that he had “accurate information” that “drones, precision missiles, and ballistic missiles will be launched from the Iraqi soil” at the United Arab Emirates. (Allegations have been made against the UAE for allegedly being part of a conspiracy against Iran-linked groups.)

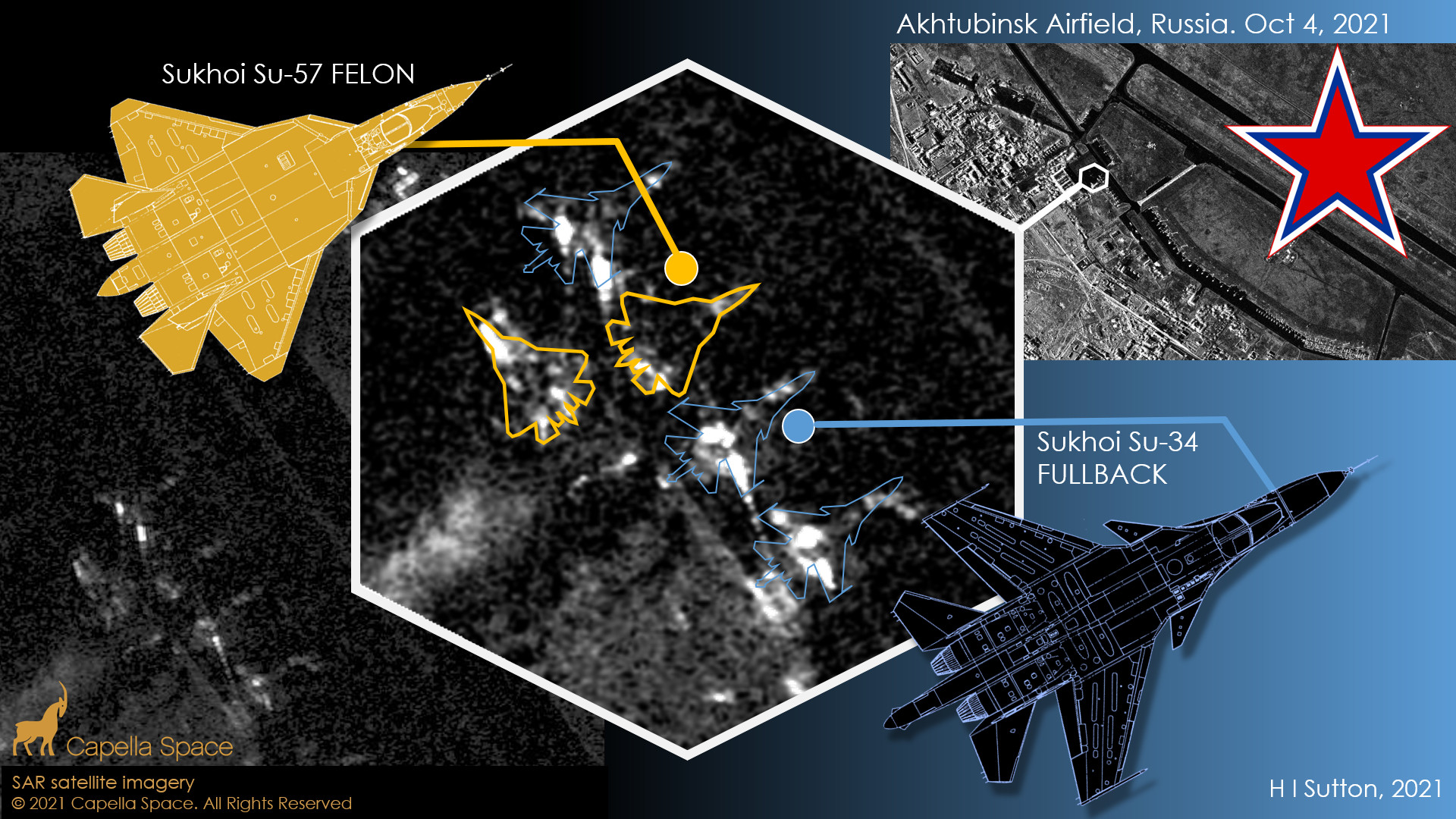

India is now a major spacefaring nation. Initially, the Indian space programme was focused primarily on societal and developmental utilities. Today, like many other countries, India is compelled to use space for several military requirements like intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance. Hence, India is looking to space to gain operational and informational advantages.

India is now a major spacefaring nation. Initially, the Indian space programme was focused primarily on societal and developmental utilities. Today, like many other countries, India is compelled to use space for several military requirements like intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance. Hence, India is looking to space to gain operational and informational advantages.