Sean Fleming

Source Link

The pace of change in the technology sector has always been brisk. As much as

10 years worth of growth in e-commerce may have been compressed into just three months in late 2019, according to McKinsey & Company, which predicts that we’ll experience more technological progress in the coming decade than we did in the preceding 100 years put together.

Any change can be unsettling and keeping pace with developments even more so. Part of the challenge is knowing which are the most significant changes and which are the ones that are less likely to bear fruit.

According to McKinsey,

these are the 10 top technologies attracting the attention and funds of investors and technologists. They are also the ones most likely to feature prominently in the changing face of the modern workplace. Understanding the impact they will have on organizations and on the people whose jobs will be affected, could be key to avoiding any of the worst downsides of the disruption that may follow.

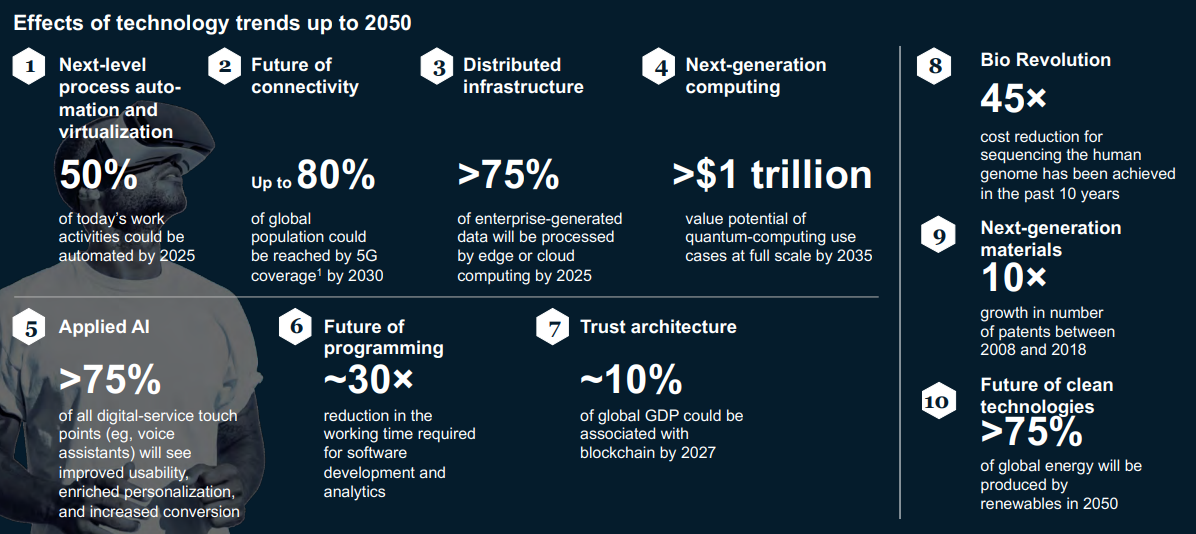

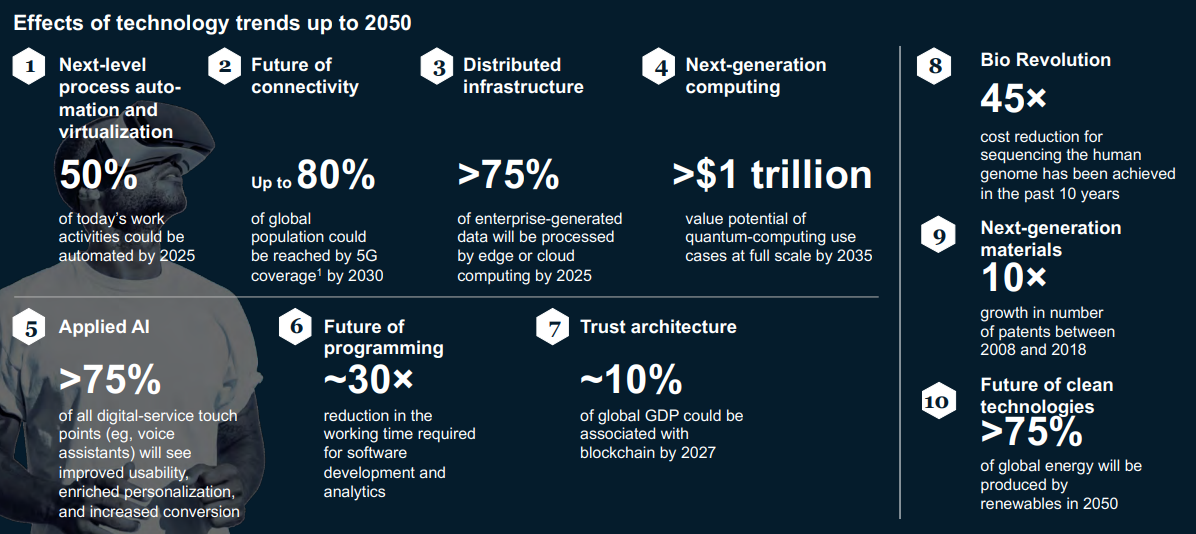

Technology trends and underlying technologies. Image: McKinsey & Co

1. Process automation and virtualization

Around half of all existing work activities could be automated in the next few decades, as next-level process automation and virtualization become more commonplace.

“By 2025, more than 50 billion devices will be connected to the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT),” McKinsey predicts. Robots, automation, 3D-printing, and more will generate around 79.4 zettabytes of data per year.

2. The future of connectivity

Faster digital connections, powered by 5G and the IoT, have the potential to unlock economic activity. So much so that McKinsey says implementing faster connections in “mobility, healthcare, manufacturing and retail could increase global GDP by $1.2 trillion to $2 trillion by 2030.”

“Far-greater network availability and capability will drive broad shifts in the business landscape, from the digitization of manufacturing (through wireless control of mobile tools, machines and robots) to decentralized energy delivery and remote patient monitoring.”

3. Distributed infrastructure

By 2022, 70% of companies will be using hybrid-cloud or multi-cloud platforms as part of a distributed IT infrastructure. It will mean data and processing can be handled in the cloud but made accessible to devices faster.

“This trend will help companies boost their speed and agility, reduce complexity, save costs and strengthen their cybersecurity defenses,” McKinsey says.

Tech trends affect all sectors, but their impact varies by industry.

4. Next-generation computing

Next-generation computing will, McKinsey believes, “help find answers to problems that have bedevilled science and society for years, unlocking unprecedented capabilities for businesses”.

It includes a host of far-reaching developments, from quantum AI to fully autonomous vehicles, and as such won’t be an immediate concern for all organizations. “Preparing for next-generation computing requires identifying whether you’re in a first-wave industry (such as finance, travel, logistics, global energy and materials, and advanced industries),” McKinsey says, or “whether your business depends on trade secrets and other data that must be safeguarded during the shift from current to quantum cryptography.”

5. Applied Artificial Intelligence (AI)

We are still only in the early days of the development of AI. As the technology becomes more sophisticated, it will be applied to further develop tech-based tools, such as training machines to recognize patterns, then act upon what it has detected.

By 2024, McKinsey estimates AI-generated speech will be behind more than 50% of people’s interactions with computers. Companies are still searching for ways to use AI effectively though, the consultancy says: “While any company can get good value from AI if it’s applied effectively and in a repeatable way, less than one-quarter of respondents report significant bottom-line impact.”

Effects of technology trends in 2050.

6. Future of programming

Get ready for Software 2.0, where neural networks and machine learning write code and create new software. “This trend makes possible the rapid scaling and diffusion of new data-rich, AI-driven applications,” according to McKinsey.

In part, it could see the creation of software applications far more powerful and capable than anything available today. But it will also make it possible for existing software and coding processes to be standardized and automated.

7. Trust architecture

In 2019, more than 8.5 billion data records were compromised. Despite advances in cybersecurity, criminals continue to redouble their efforts. Trust architectures will help in the fight against cybercrime, McKinsey says.

One approach to building a trust architecture is the use of distributed ledgers, such as blockchain. “In addition to lowering the risk of breaches, trust architectures reduce the cost of complying with security regulations, lower the operating and capital expenditures associated with cybersecurity, and enable more cost-efficient transactions, for instance, between buyers and sellers,” McKinsey notes.

8. Bio Revolution

There is, McKinsey says, a “confluence of advances in biological science” that “promises a significant impact on economies and our lives and will affect industries from health and agriculture to consumer goods, energy and materials.”

Propelled by AI, automation and DNA sequencing, the bio revolution promises the development of gene-therapies, hyper-personalized medicines and genetics-based guidance on food and exercise. These developments will create new markets but will also raise some important ethical questions. “Organizations need to assess their bQ or biological quotient – the extent to which they understand biological science and its implications. They should then sort out the resources they need to allocate to biological technologies and capabilities and whether to integrate those into their existing R&D or partner with science-based start-ups,” McKinsey says.

9. Next-generation materials

Developments in materials science have the potential to transform multiple market sectors, including pharma, energy, transportation, health, semiconductors and manufacturing. Such materials include graphene – a single layer of carbon atoms arranged in a honeycomb lattice configuration, which is around 200 times stronger than steel, despite its incredible thinness. It is also a very efficient conductor and promises to revolutionize semiconductor performance. Another is molybdenum disulfide – nanoparticles of which are already being used in flexible electronics.

“By changing the economics of a wide range of products and services, next-generation materials with significantly higher efficiency in many as-yet-untouched application areas may well change industry economics and reconfigure companies within them,” McKinsey says.

10. Future of clean technologies

Renewable energy, cleaner/greener transport, energy-efficient buildings and sustainable water consumption are at the heart of the clean-tech trend. As the costs associated with clean-tech fall, their use becomes more widespread and their disruption is felt across a growing number of industries, McKinsey says.

“Companies must keep pace with emerging business-building opportunities by designing operational-improvement programmes relating to technology development, procurement, manufacturing and cost reduction,” McKinsey believes. “Advancing clean technologies also promises an abundant supply of green energy to sustain exponential technology growth, for instance, in high-power computing.”

The Deterrence Theory was developed in the 1950s, mainly to address new strategic challenges posed by nuclear weapons from the Cold War nuclear scenario. During the Cold War, the U.S. and the Soviet Union adopted a survivable nuclear force to present a ‘credible’ deterrent that maintained the ‘uncertainty’ inherent in a strategic balance as understood through the accepted theories of major theorists like Bernard Brodie, Herman Kahn, and Thomas Schelling.1 Nuclear deterrence was the art of convincing the enemy not to take a specific action by threatening it with an extreme punishment or an unacceptable failure.

The Deterrence Theory was developed in the 1950s, mainly to address new strategic challenges posed by nuclear weapons from the Cold War nuclear scenario. During the Cold War, the U.S. and the Soviet Union adopted a survivable nuclear force to present a ‘credible’ deterrent that maintained the ‘uncertainty’ inherent in a strategic balance as understood through the accepted theories of major theorists like Bernard Brodie, Herman Kahn, and Thomas Schelling.1 Nuclear deterrence was the art of convincing the enemy not to take a specific action by threatening it with an extreme punishment or an unacceptable failure.