DEAN CHENG

Source Link

How will the ripples from the Afghanistan debacle affect American policy on China? One potential metric will be the number of states that choose to welcome China’s Huawei into their 5G environments. With Washington demonstrating little competency or reliability, Beijing is likely to press countries to include Huawei and other Chinese telecommunications corporations in their 5G networks, lest they alienate Beijing. Should European and other states quietly reverse their previous positions, and choose to allow Beijing in, the ultimate price for the Afghan failure may reverberate for years to come.

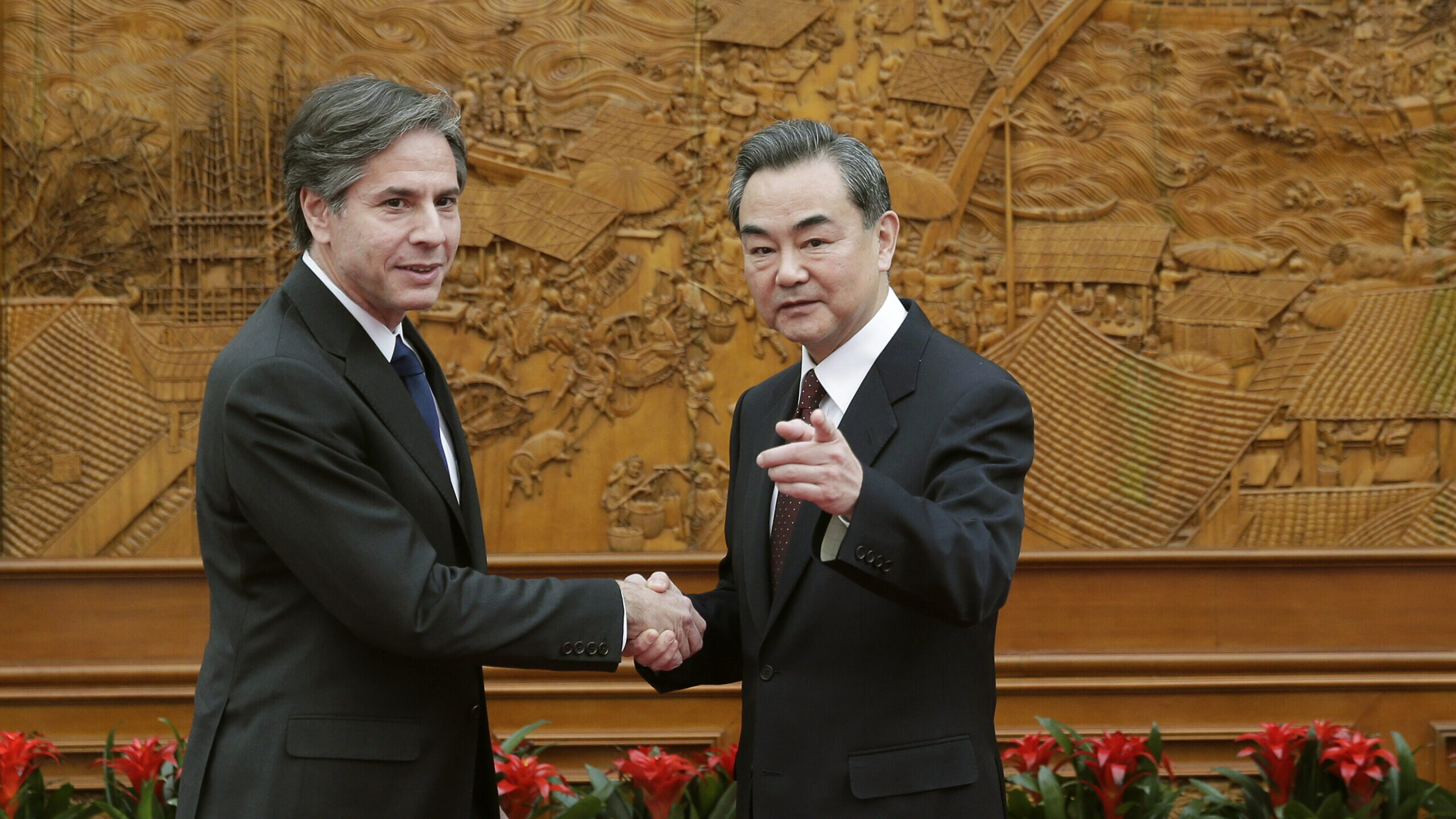

Amidst the terrible news coming out of Afghanistan over the past weeks was a little noticed announcement that came out after Secretary of State Antony Blinken approached his Chinese counterpart Wang Yi in late August. Even the bland American statement makes it clear that the United States was approaching the People’s Republic of China (PRC) to seek its assistance:

The Chinese version is far more caustic. According to the Chinese foreign ministry, Wang Yi castigated the US for its hostility to China, and made clear that any cooperation would be predicated on the United States changing its approach to China. Indeed, Wang took the opportunity to insist, again, that the United States implement the policy changes it presented to Deputy Secretary of State Wendy Sherman on her visit to Tianjin earlier this year.

Blinken’s imploring of the Chinese for assistance and support in Afghanistan, in combination with the diplomatic fiascos in Anchorage and Tianjin, are emblematic of how the United States is ceding ground to the People’s Republic of China. The debacle in Afghanistan only further opens doors for Beijing. Defeat has consequences.

Fortunately, China is unlikely to take advantage of this turmoil and invade Taiwan. While Taipei authorities have expressed concern about the consequences of the Afghanistan debacle, the pressure from the PRC is far more likely to be political than military. The collapse of the government and military in Afghanistan came so quickly that even the PRC is likely to have been caught off-guard. Given the difficulties of launching an amphibious invasion under the best of circumstances, it is unlikely that the PRC leadership would decide to throw together an invasion of Taiwan. Unlike the American decision to withdraw forces in the middle of “campaign season” in Afghanistan, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) would have to think very hard about whether it would want to risk an amphibious assault in the midst of typhoon season. Instead, Beijing has redoubled its political warfare efforts, messaging Taiwan that Afghanistan demonstrates that the United States is unreliable.

Nor does it mean that Beijing is about to step into the Afghan quagmire. Wang Yi’s comments make very clear that the Chinese see no need to intervene themselves in the Afghan situation. Moreover, it is vital to recognize that Beijing has a trump card that the United States has never possessed: enormous influence over Pakistan, the prime sponsor and supporter of the Taliban. Indeed, the Pakistani security services had played a key role in the creation and sustainment of the Taliban, even before 9/11.

China-Pakistan ties have long been close, ever since Pakistan was the third country to recognize the fledgling People’s Republic of China in 1950. Pakistan has described China as its “all weather friend,” in sharp contrast to the United States, its “fair weather friend.” Pakistan is far more likely to press the Taliban to not make trouble for the Chinese (e.g., by training Uyghurs), if only to maintain good ties to the PRC. Such pressure is likely to be taken quite seriously by the Taliban leadership.

What Beijing gains from the American debacle is, first and foremost, a massive gain in its public opinion warfare efforts. One of the “three warfares,” “public opinion warfare” (sometimes also translated as “media warfare”) is the use of mass information channels, including the internet, social media, television, radio, newspapers and movies, to transmit selected news and messages to the intended audience. It occurs in accordance with an overall plan and defined objectives, and seeks to shift both mass and leadership views and opinions.

The goal is not simply to expose a particular point of view, but to actively generate support at home and abroad, alter the perceptions of both the adversary and third parties and eventually shift situational assessments (and consequently strategic decisions) by friends, enemies, and third parties. It is closely tied to “psychological warfare” and “legal warfare,” the other parts of the “three warfares” triad.

Beijing wasted no time signaling the implications of the chaotic American withdrawal to Taiwan. Various Chinese media outlets promptly began warning the Taiwan population that any expectation of American succor in event of a conflict was misplaced. After all, if the United States would not support Afghanistan, where it had spent trillions of dollars and thousands of lives, and fought for 20 years, why should Taipei believe that Washington would be more committed to its security?

Coincidentally, other Chinese security developments are reinforcing Beijing’s message. The discovery, for example, of three fields of nuclear silos in western China underscores that China is an expanding nuclear power. Over the past two decades, Chinese military officers have noted that China’s nuclear capabilities complicate American decisions over Taiwan, and have warned that China’s nuclear no-first-use policy may not be absolute. Undertaking a massive expansion of its nuclear weapons capabilities in a visible way underscores that any American support for Taiwan occurs in the shadow of China’s growing nuclear umbrella.

The chaotic American withdrawal unintentionally reinforces Beijing’s point. There is no reason to think that there is any deliberate relationship between these two events, but the impact is nonetheless reinforcing China’s message, helping intensify Chinese “public opinion warfare.”

This broader public opinion warfare message, aimed at the wider, global audience, is also in full swing. Xinhua declared that the defeat in Afghanistan, coming on the heels of the COVID-19 pandemic and the earlier financial crises, signaled the end of American hegemonism. Similarly, Chinese foreign minister Wang Yi’s comments that American-induced tensions in the US-China relationship were jeopardizing efforts to combat global climate change are clearly intended to resonate globally.

What is even more problematic is that these same questions are undoubtedly being asked, unbidden, in capitals around the world even where Beijing isn’t pressing the issue. The PRC doesn’t have to try and create an image of American unreliability and potential incompetence. It merely has to point to the chaos at Kabul airport and the inexplicable decision to pull American military forces out while there were still tens of thousands of civilians inside Afghanistan. The longer Americans remain trapped in Afghanistan (and American diplomats insist that there are no stranded Americans), the more Beijing’s points appear to be borne out.

The Deterrence Theory was developed in the 1950s, mainly to address new strategic challenges posed by nuclear weapons from the Cold War nuclear scenario. During the Cold War, the U.S. and the Soviet Union adopted a survivable nuclear force to present a ‘credible’ deterrent that maintained the ‘uncertainty’ inherent in a strategic balance as understood through the accepted theories of major theorists like Bernard Brodie, Herman Kahn, and Thomas Schelling.1 Nuclear deterrence was the art of convincing the enemy not to take a specific action by threatening it with an extreme punishment or an unacceptable failure.

The Deterrence Theory was developed in the 1950s, mainly to address new strategic challenges posed by nuclear weapons from the Cold War nuclear scenario. During the Cold War, the U.S. and the Soviet Union adopted a survivable nuclear force to present a ‘credible’ deterrent that maintained the ‘uncertainty’ inherent in a strategic balance as understood through the accepted theories of major theorists like Bernard Brodie, Herman Kahn, and Thomas Schelling.1 Nuclear deterrence was the art of convincing the enemy not to take a specific action by threatening it with an extreme punishment or an unacceptable failure.

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/mco/SGNFQSHULRFZ7NAWQDRHXXP4FY.jpg)