Tod Strickland

The commissions given to new officers, almost regardless of nation or service, are similar. They make it abundantly clear that officership is about duty and responsibility. Accepting that the office and rank may change, officers are charged with meeting the demands of their station regardless of whether that station is well defined. This implies a need for continual education and personal development matching one’s progress through ever greater responsibilities. Acknowledging that how officers think affects the nation’s success or failure, it is imperative that their formal training and education, as well as self-development be shaped to meet a nation’s needs.

The commissions given to new officers, almost regardless of nation or service, are similar. They make it abundantly clear that officership is about duty and responsibility. Accepting that the office and rank may change, officers are charged with meeting the demands of their station regardless of whether that station is well defined. This implies a need for continual education and personal development matching one’s progress through ever greater responsibilities. Acknowledging that how officers think affects the nation’s success or failure, it is imperative that their formal training and education, as well as self-development be shaped to meet a nation’s needs.

But, what should officers study to shape how prepared they will be for what may come? Perspectives on this topic vary. The reading lists from the various services demonstrate there is a definite canon of professional military thought that potential students can work through.[2] Examining the issue more broadly though, other questions quickly emerge—why do officers think like they do, do their patterns of thought meet contemporary needs, and how can we improve how officers think? Reed Bonadonna gives these questions book-length consideration in How to Think Like an Officer: Lessons in Learning and Leadership for Soldiers and Other Citizens.[3]

Bonadonna is eminently qualified to give the subject fair treatment. A former infantry officer and field historian with the United States Marine Corps, he possesses operational experiences that positively influence his perspective. A Ph.D. in English literature, he has devoted significant portions of his life to studying and teaching about leading within the profession of arms at the United States Marine Corps Command and Staff College and at the United States Merchant Marine Academy. Currently the senior fellow at the Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs, his perspectives are well-informed and enlightening.

Bonadonna’s main position is that “thinking like an officer is the most defining aspect of military professionalism, more than values, character, or knowledge, and that it has been neglected in officer education.”[4] Secondarily, he asserts that the level of contemporary thinking in the officer corps is inadequate for current needs.[5] These ideas, largely treated as facts, are not strongly argued within the volume, but instead allow the author to expound on the topics that he believes should be foundational to educating officers in how to think and how to meet the demands of the profession of arms.

The author has essentially produced a syllabus for self-development, which can also be used as an effective tool for anyone concerned with formal professional military education. Structured in two distinct parts—Thinking and Learning is the first, and Thought and Action is the second—the book provides a ready reference for anyone seeking to target their own development based on their time within the profession or the specific roles they occupy. Moving beyond the military, the author concludes with a chapter aimed at civilian readers who may seek to emulate some or all of the qualities that make a military officer effective. This chapter should be read by all, as Bonadonna makes some good points about understanding how the military thinks and operates. It is useful for addressing current gaps in understanding the military and its place in the wider society.

The need for officers to be life-long learners, invested in their own self-development, is not new. Authors Richard Swain and Albert Pierce have asserted, in the most current version of The Armed Forces Officer, “Armed Forces officers have the…responsibility of…engaging in continuous personal learning by study and reflection so they themselves are fit to command when that day arrives….”[6] Similarly, Chairman of the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff General Mark Milley, in recent testimony to Congress, made specific mention of the need for all those in uniform to be “open minded and widely read.”[7] While headlines may have been more focused on the appropriateness of leaders within the U.S. military learning about Critical Race Theory, the concept of military leaders being lifelong learners was evident within the Chairman’s words:

I do think it’s important for those of us in uniform to be open-minded and be widely read…Our soldiers, sailors, airmen, Marines, and guardians—they come from the American people. It’s important that the leaders, now and in the future, understand it…It matters to the discipline and cohesion of this military.[8]

Most Western armies include the idea of self-development as part of either their expectations of officers or as part of their relevant training and educational frameworks. The Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) includes self-development as one of the four pillars—along with education, training, and experience—of its professional development framework.[9] The Australian military, in their recently published Defence Enterprise Learning Strategy 2035, has made the development of an “intellectual edge” a key strategic goal, which is in turn reliant on creating learners who “embrace a commitment to continuous learning and develop an inquisitiveness and curiosity that sees them pull content and learning to them.”[10] This fact gives Bonadonna’s work wider applicability than might first be anticipated.

This is a unique book, particularly in how it anticipates that its readers will want more information; it treats the reader as an active participant in the exercise of self-development. Each chapter is extensively sourced and researched, making use of a dizzying variety of sources and associated ideas. The text is permeated with recommendations for further reading, both fiction and non-fiction, that illustrate both the scope of the author’s grasp of the subject matter, and the reality that being widely read needs to encompass more than just the standard reading lists promulgated by the military institutions. The book's bibliography is a gold-mine for any reader interested in obtaining a more detailed understanding of the ideas that Bonadonna presents—if only it were the case that every non-fiction book offered its readership the same resource.

The person of General George C. Marshall is present throughout the book. Understanding the central role Marshall played in both the U.S. Army and later public service, Bonadonna’s references to him are in some ways unsurprising. Marshall remains a seminal figure as the quintessential American military professional—apolitical, dignified, intelligent, courageous, and duty bound. His influence on the author is clear, and it manifests as a consistent touchpoint to the past and an aimpoint for the future.

A salute to George Mashall (Encyclopedia Virginia)

The assumptions that underpin the volume do raise questions that could, and likely should, have been more fully addressed. In the first instance, arguing that how officers think is more important than either their character or their sense of ethics is debatable. One who has worked for an incredibly intelligent leader lacking in their moral framework might argue that character matters more than thought patterns or even intelligence. The point here is not to decide which takes precedence, however. It is simply that the topic warranted a broader discussion than it received. It is also a question that all officers need to consider and address.

Similarly, asserting contemporary methods of thinking are not sufficient for our current needs without fully arguing the case may leave readers wanting. There are simply too many possible causal alternatives that warrant discussion. While the author points towards military culture and the education process, these are but two possibilities. The social context in which officers must operate, legislative frameworks, and operating environments could all be seen as possible causes for perceived deficiencies in the state of officer thought as a whole. As an example, has any other generation of officers had to fight a multi-decade war, while pursuing Masters degrees, in a polarized political environment? Arguing it is the methods by which officers think without a more detailed examination of the context is problematic. In fairness to the author, however, he does highlight the specific ways that failure is manifesting itself within the American officer corps while being clear that he blames their education and contemporary military culture.

The linkage between military culture and how an officer might think is worth reflection. Military culture and how members of the profession, admittedly not necessarily solely the officer corps, think have a symbiotic relationship—feeding one another, informing the ideas and perspectives of the military community, and in turn shaping the mental models that get propagated.

It is reasonable to question whether how officers think has shaped the current problem set. If one accepts that the manner of thinking is a root cause of extant cultural issues, one needs to consider whether the self-development and the formal education we give our officers is sufficient. Reinforcing the linkage between wider society and the profession of arms, certain elements warrant a renewed emphasis—civic mindedness and politics, history, character, and ethics—as Bonadonna alludes to.

We may need to re-emphasize certain elements within an officer’s education—civic mindedness, politics, history, character, and ethics, to name but a few.

How to Think Like an Officer is an excellent resource and a thought-provoking read. The ideas that Bonadonna espouses for improving officer education and for widening the lenses that get used to examine problems have much to commend them. His arguments that there are elements of military culture that need to be re-examined and changed will certainly raise questions, but this is a good thing. As Albert Einstein once said, “We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them.”[11] Investing in the time to examine how officers think, and considering how we can improve upon the status quo, is an investment worth making. Arguably, doing so is a requirement of anyone belonging to the military profession.

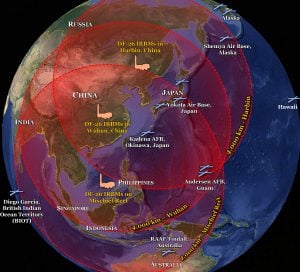

The Deterrence Theory was developed in the 1950s, mainly to address new strategic challenges posed by nuclear weapons from the Cold War nuclear scenario. During the Cold War, the U.S. and the Soviet Union adopted a survivable nuclear force to present a ‘credible’ deterrent that maintained the ‘uncertainty’ inherent in a strategic balance as understood through the accepted theories of major theorists like Bernard Brodie, Herman Kahn, and Thomas Schelling.1 Nuclear deterrence was the art of convincing the enemy not to take a specific action by threatening it with an extreme punishment or an unacceptable failure.

The Deterrence Theory was developed in the 1950s, mainly to address new strategic challenges posed by nuclear weapons from the Cold War nuclear scenario. During the Cold War, the U.S. and the Soviet Union adopted a survivable nuclear force to present a ‘credible’ deterrent that maintained the ‘uncertainty’ inherent in a strategic balance as understood through the accepted theories of major theorists like Bernard Brodie, Herman Kahn, and Thomas Schelling.1 Nuclear deterrence was the art of convincing the enemy not to take a specific action by threatening it with an extreme punishment or an unacceptable failure.

T

T