By Steven Erlanger

NATO foreign and defense ministers agreed on Wednesday to begin withdrawing forces from Afghanistan on May 1 following the announcement from President Biden that U.S. forces will leave by Sept. 11.

“Currently, we have around 10,000 troops in Afghanistan, the majority from non-U.S. allies and partner countries. We have been closely consulting on our presence in Afghanistan for the last weeks and months. In the light of the U.S. decision to withdraw, foreign and defense ministers of NATO discussed the way forward today, and decided that we will start the withdrawal of NATO support mission forces by May 1.” “Twenty years ago after the United States was attacked on 9/11, this alliance invoked Article 5 for the first time in its history. An attack on one is an attack on all. Together, we went to Afghanistan to root out al Qaeda, and prevent future terrorist attacks from Afghanistan directed at our homeland. Now, we will leave Afghanistan together and bring our troops home.” “Our troops have accomplished the mission that they were sent to Afghanistan to accomplish. And they have much for which to be proud. Their services and their sacrifices, alongside those of our resolute support of Afghan partners, made possible a greatly diminished threat to all of our homelands and homelands of al Qaeda and other terrorist groups.”

BRUSSELS — Following the news that the United States was pulling all its troops from Afghanistan by Sept. 11, NATO’s foreign and defense ministers agreed on Wednesday to begin withdrawing NATO forces on May 1 and finish “within a few months,” the alliance said in a statement.

The withdrawal will be “orderly, coordinated and deliberate,’’ the statement said, adding: “Any Taliban attacks on allied troops during this withdrawal will be met with a forceful response.”

The allies support efforts for “an Afghan-owned and Afghan-led peace process,” the statement said, and called the withdrawal “the start of a new chapter.’’

At the moment, of the 9,600 NATO troops officially in Afghanistan, about 2,500 of them are American, though that number can be as many as 1,000 higher. The second-largest contingent is from Germany, with some 1,300 troops.

In a news conference after the meeting with Secretary of Defense Lloyd J. Austin III, Secretary of State Antony J. Blinken said that the NATO troop withdrawal by Sept. 11 did not mean an end to the American commitment to Afghanistan, which would include aid and advice to the military and to the government. Today, he said, NATO “began to hammer out what ‘out together’ looks like.”

The Earth did not change its shape. Southwestern Asia did not change its borders. No additional terrorists laid down their arms. But suddenly we’ve resolved one of the most important reasons for keeping U.S military forces in Afghanistan?

The Earth did not change its shape. Southwestern Asia did not change its borders. No additional terrorists laid down their arms. But suddenly we’ve resolved one of the most important reasons for keeping U.S military forces in Afghanistan?

On 19 March, the leaders of four important democracies of the Indo-Pacific region – the United States, Japan, Australia and India – held (virtually) their first-ever “Quad Summit.” This meeting at the leaders’ level of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue was significant on two counts.

On 19 March, the leaders of four important democracies of the Indo-Pacific region – the United States, Japan, Australia and India – held (virtually) their first-ever “Quad Summit.” This meeting at the leaders’ level of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue was significant on two counts.

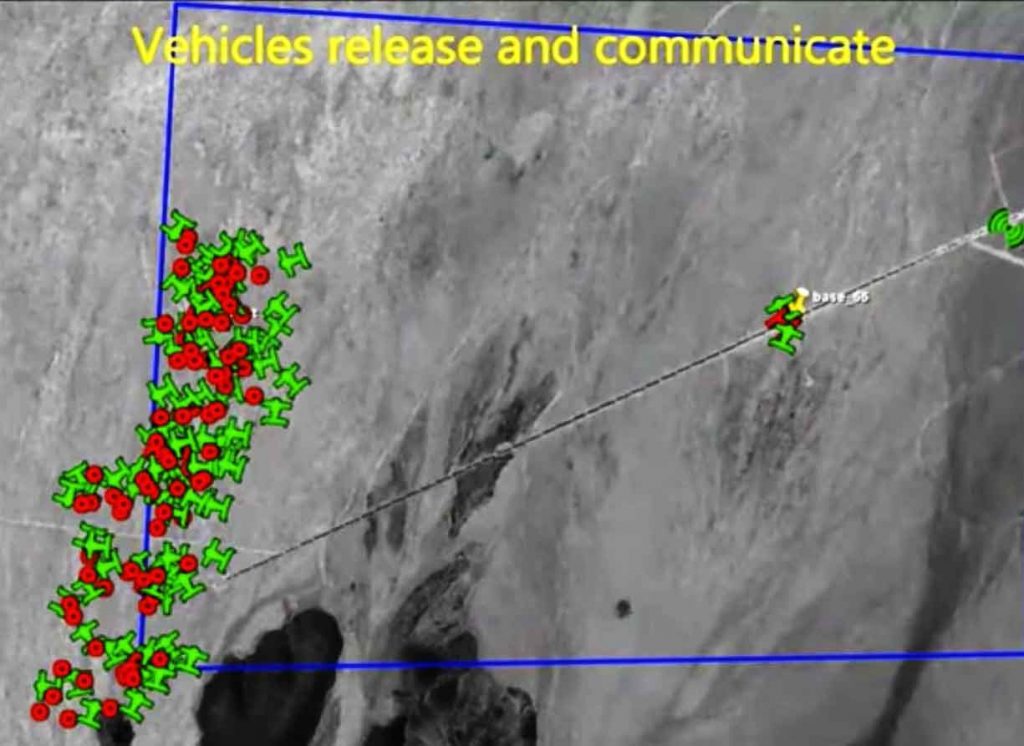

Here's What You Need to Remember: AI-capable drone defenses can already gather, pool, organize and analyze an otherwise disconnected array of threat variables, compare them against one another in relation to what kinds of defense responses might be optimal and make analytical determinations in a matter of milliseconds.

Here's What You Need to Remember: AI-capable drone defenses can already gather, pool, organize and analyze an otherwise disconnected array of threat variables, compare them against one another in relation to what kinds of defense responses might be optimal and make analytical determinations in a matter of milliseconds.