BY MICHAEL HIRSH

Clinton, then the U.S. secretary of state, was in Yangon, Myanmar, to sit down with the woman she called her “inspiration” as part of a broader, if undeclared, U.S. strategy to drive a wedge between nations on China’s perimeter and Beijing, including long-isolated Myanmar, under the aegis of the Obama administration’s “pivot” to Asia. And during a tenure at the State Department in which Clinton hadn’t accomplished much beyond hard-toned speeches and “soft” diplomacy, her opening to Myanmar was a rare diplomatic victory. A year later, Barack Obama became the first sitting U.S. president to visit the country, ostensibly to promote democracy, but also to nudge Myanmar closer to Washington’s sphere of influence.

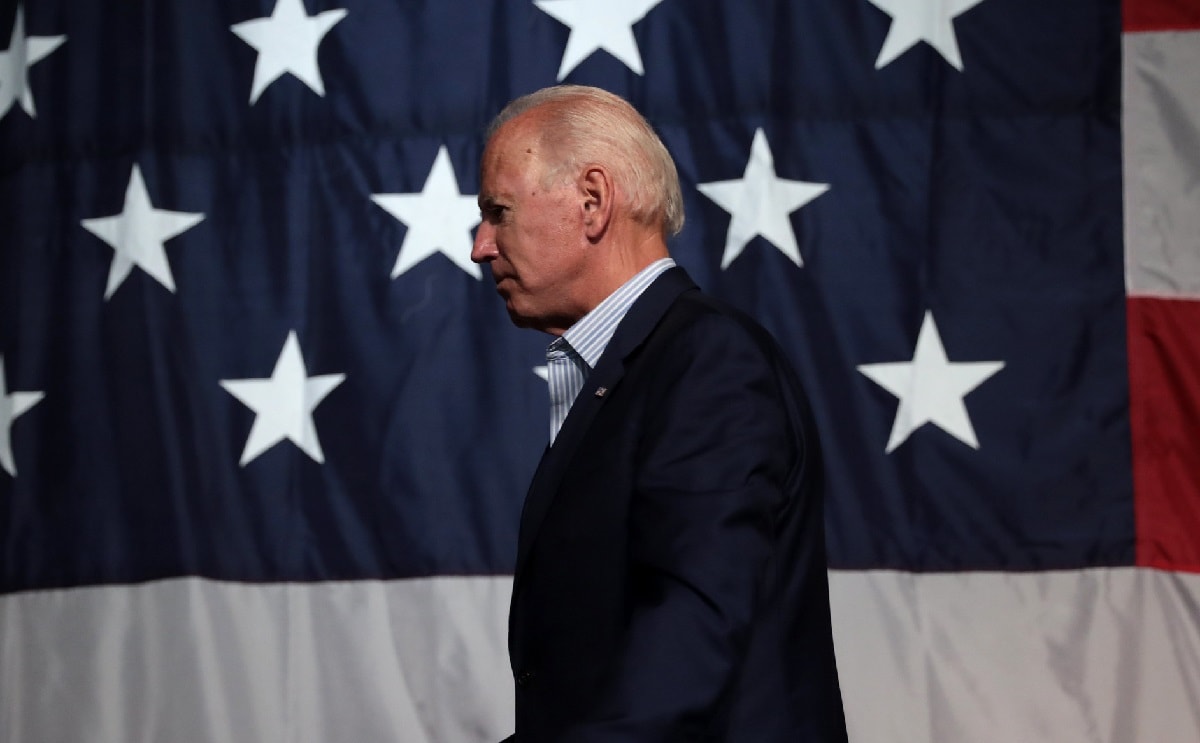

A decade later, that strategy lies in ruins. Aung San Suu Kyi, the Nobel Prize-winning democracy activist who hosted Clinton and later ran the country, is back in detention after the military launched yet another coup on Monday. Nor is there much diplomacy afoot: Such is her estrangement from Washington today that in the week before Aung San Suu Kyi’s arrest, the Biden administration, fearing just this outcome, had tried and failed to get in contact with her.

But if the U.S. strategy is in ruins, so is Aung San Suu Kyi’s reputation. While many in the West have in recent days called for her release, she is no longer the heroine and human-rights icon she once was. Her cold-blooded assent to the army’s slaughter of the Muslim Rohingya minority has soured her image around the world, to the point where some democracy activists have petitioned Oslo to revoke her Nobel. Once a magnet for human rights pressure on Myanmar from abroad, today she remains largely isolated internationally.

The coup that seems to have hurled Myanmar back three decades is another grim 21st-century lesson in the difficulties of democracy and the staying power of authoritarianism—and the limitations of diplomacy in building a bridge between the two.