NIKOLA MIKOVIC

Russian President Vladimir Putin does not seem ready to burn his bridges with the West just yet, judging by his highly anticipated end-of-year speech delivered on December 23.

Despite threats and harsh rhetoric amid a threatened war on Ukraine, the Russian leader at the same time says that the United States’ response to the Kremlin’s demands for legally binding security guarantees to defuse the stand-off has been “positive”, even though Washington still has not formally responded to Moscow’s proposals.

Does that mean Russia is actually not poised to invade the neighboring country that was part of the former Soviet Union?

Not necessarily. If Ukraine launches a full-scale military offensive in the Donbass, Moscow will likely have to intervene to protect the self-proclaimed Donetsk People’s Republic and Lugansk People’s Republic.

Otherwise, the West would interpret Russia’s lack of a firm response as another sign of weakness, and eventually Ukraine, strongly supported by the United States, could seek to restore its sovereignty over Crimea.

“The future of the Donbass has to be decided by the people living in the Donbass,” said Putin during his highly anticipated end-of-year press conference.

The people of the Donbass, of course, already decided their future in May 2014 when they held a referendum and declared “self-rule”, or de facto independence from Kiev. To this day, however, the Kremlin refuses to recognize the referendum.

But in case of a potential Ukrainian offensive, Russia may implement the same strategy it used in 2008 after Georgia attacked its breakaway region of South Ossetia. Moscow intervened, expelled Georgian forces from the region and recognized the independence not only of South Ossetia but also of Abkhazia.

Given that west Ukraine has a far greater strategic and economic importance than Georgia, such a Russian action would result in severe sanctions that would negatively impact on Russia’s economy. In order to prevent such a scenario, the Kremlin is now demanding “security guarantees” that NATO will not expand eastward into Ukraine.

A Russian soldier takes aim along the Ukrainian border. Photo: Facebook

A Russian soldier takes aim along the Ukrainian border. Photo: Facebook“You must give us guarantees, and immediately – now”, Putin said.

It remains unclear, though, why the Kremlin is in such a hurry. In early October former Russian president Dmitry Medvedev penned an article in which he pointed out that “Russia knows how to wait”, and that Moscow should wait until “sane figures” come to power in Kiev and replace the current Ukrainian leadership.

Two months later, however, Putin is pressuring the United States to promise that Ukraine will not join NATO. The alliance has already ruled out any compromise over NATO’s “key principles”, which means that the West will almost certainly not provide the “security guarantees” Putin seeks.

What will Moscow do in that case?

“The United States needs to understand that we simply have nowhere else to go. Do they think we’re going to stand by and watch,” Putin said a couple of days before his annual year-end media conference, claiming that the US could push Kiev to attack Crimea.

To be sure, such rhetoric from Putin is nothing new. In August 2016, Putin accused the Ukrainian Defense Ministry of killing a Russian soldier and a Federal Security Service (FSB) officer in Crimea, at the border with Ukraine.

Apparently, Ukraine sent a sabotage-reconnaissance group to Crimea, which resulted in a brief border clash. Putin said Russia would “not let such things slide by,” but Moscow never responded to the alleged killing of its military and intelligence personnel.

Thus, if Ukraine eventually really stages massive provocations in Crimea, Russia’s response may not be as fierce as some might expect.

Although the Kremlin claims that Ukraine and the United States are preparing to “commit provocations” that could include a chemical attack, such a scenario does not seem very realistic. Russia has a history of ringing such “false alarms” in Syria.

For instance, in 2017, Moscow accused Washington of concocting a “provocation” in Syria, while a year later the Kremlin claimed that rebels were planning a chemical weapons attack with the intent of blaming it on Syria’s President Bashar al-Assad.

In November this year, Russia’s Defense Ministry warned that Turkey-backed militants plan to stage a provocation and use chemical weapons against civilians in the Middle Eastern country.

Given that no chemical provocation ever took place, it seems unlikely that Kiev and Washington will launch such an adventure in Crimea either.

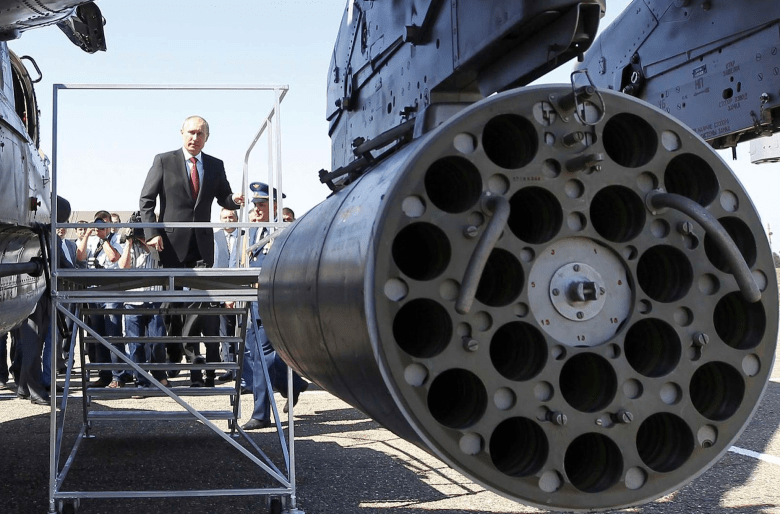

Russian President Vladimir Putin inspects a ground-attack helicopter at a base in Korenovsk, in western Russia. Putin has supplied advanced defensive missile systems to Syria. Photo: AFP / Mikhail Klimentyev / Pool

Russian President Vladimir Putin inspects a ground-attack helicopter at a base in Korenovsk, in western Russia. Putin has supplied advanced defensive missile systems to Syria. Photo: AFP / Mikhail Klimentyev / PoolWhat is almost certain, however, is that the United States will not fulfill Russia’s demands and provide guarantees that NATO will not expand eastward.

Russian officials, for their part, claim to have a plan B in case the US and NATO do not respond to Moscow’s proposals, although they refuse to say what actions the Kremlin would take.

Such a narrative was advanced in 2014, when the myth of Putin’s so-called “cunning plans” was born. In reality, Russia’s actions have always been rather limited, calculated and carefully coordinated with its Western partners.

Even now, amid fears of a large-scale conflict between Russia and Western-backed Ukraine, Russian military officials often hold talks with their Western counterparts. Even so, a potential Ukrainian offensive in the Donbass is not out of the question.

“One gets the impression that a third military operation is being prepared in Ukraine and they are warning us – do not interfere. We must somehow react to this”, Putin stressed in his speech.

Indeed, the Kremlin will react. But Moscow is more likely to yet again implement half measures, aiming to preserve its de facto control over the Donbass while at the same time not blowing up its relations with the West.

No comments:

Post a Comment