George Friedman

Two weeks ago, I wrote an analysis of Russian strategy titled “Russia’s Move.” Here’s a brief recap: When the Soviet Union collapsed, it lost control of the western borderlands that had been the bedrock of its security for hundreds of years. Those borderlands created a strategic depth that forced invaders into an extended and exhausting campaign that Russia could resist. Russia had been attacked in the 18th century by the Swedes, in the 19th century by France, and twice in the 20th century by Germany. There had also been wars with Turkey in the 18th and 19th centuries. In 1991, these borderland regions became independent, and from the Russian point of view, the West generally and the United States specifically sought to control the newly formed states. This constituted nothing less than an existential threat to Russia.

A few days after “Russia’s Move,” I wrote a piece called “Intelligence and Love,” in which I argued that to defeat an enemy you must objectively understand how they see themselves. And for its part, Russia sees itself as vulnerable, particularly from the west, where the most dangerous threats have historically originated. Belarus and Ukraine are the heart of Russian fears. The Ukrainian border is only a few hundred miles from Moscow and is therefore a major threat when in the hands of enemies. Distance will not wear down an enemy attacking from there. From the Russian point of view, the unwillingness of the United States to recognize these deep-seated fears suggests the United States has aggressive and dangerous designs. The only imaginable value Belarus and Ukraine hold for the Americans is to put Russia in a position where it must capitulate to the United States on all critical matters – or risk an outright invasion. Where the United States has no overriding interests, Russia has existential ones.

Russia must therefore act. In Belarus, it already has. Last year, President Alexander Lukashenko won a dubious and heavily criticized election. The Russians intervened to save Lukashenko and are now in effective control of Belarus, thereby securing the North European Plain, the primary invasion route from Europe to Moscow. This leaves Ukraine, a much larger and more important state, in Russia’s crosshairs.

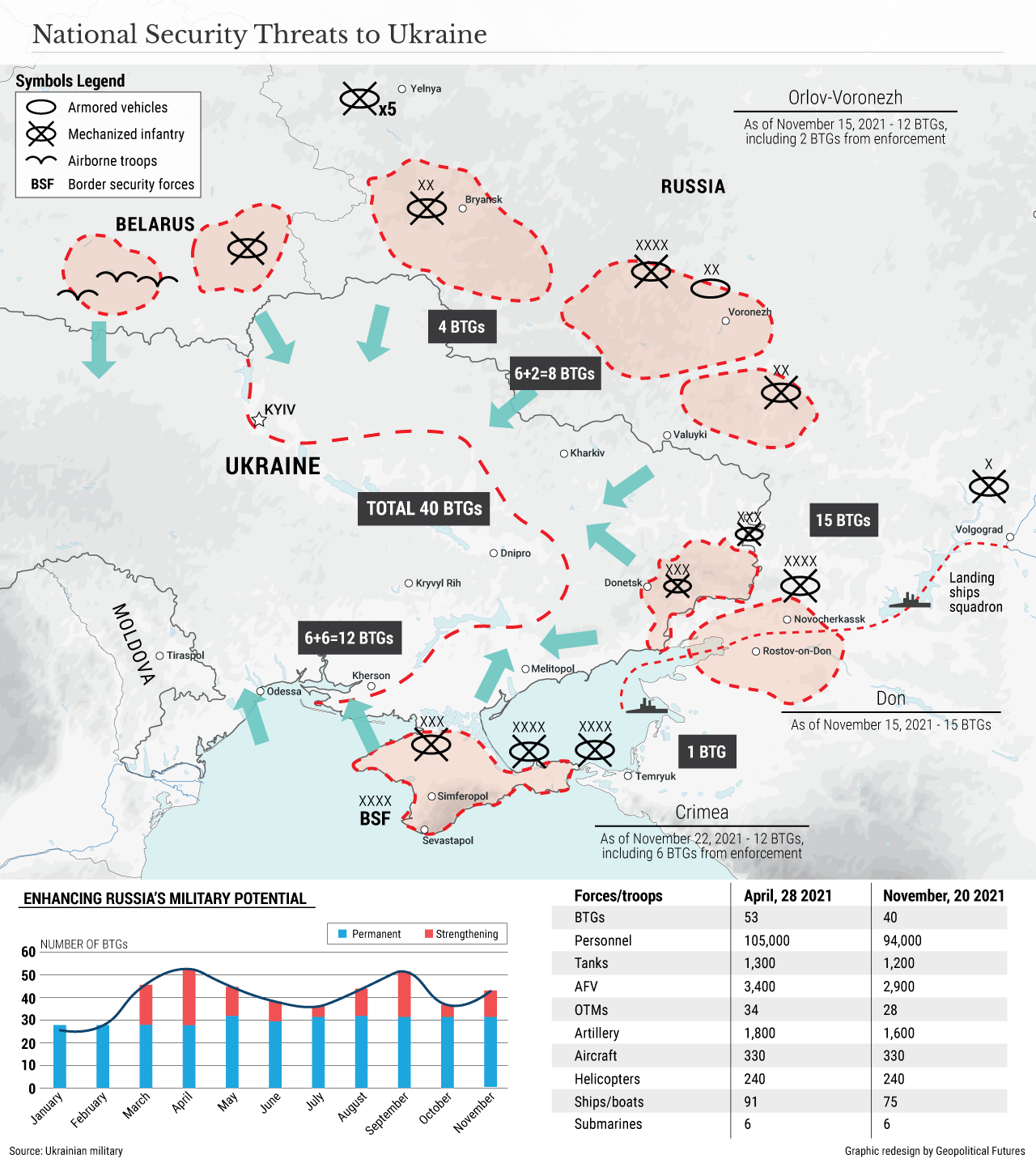

Russia appears to have amassed forces along the Ukrainian border. It is believed to be a substantial contingent. If the purpose is to occupy Ukraine, it is not enough to defeat the Ukrainian army, but it could physically occupy key areas of the country. In invading a country, the need to continually detach forces to occupy and pacify various areas can rapidly overstretch your forces. So if the reports are true, this is a risky play.

Russia’s war plan is obviously secret, but the government of Ukraine has released its view of how a Russian invasion would be executed. It consists of three thrusts intended to isolate and occupy Kyiv: northward from the Crimean Peninsula, southward from Belarus and westward from Volgograd. Together, they would surround Kyiv and pass through a substantial part of Ukraine, giving them maximum opportunity for low-cost pacification.

There are three problems with the strategy. The first problem is logistical. These multi-division forces would be engaged in high-intensity maneuver and combat. All three would have to be supplied, and as they approached Kyiv they would take on a circular formation. Since it must be assumed that combat increases as movement declines, one phase would require massive amounts of “POL” – petroleum, oil and lubricants. The second phase would demand large amounts of munitions of all varieties. The possibility is high of uncoordinated pauses in advancing, leaving Russian flanks open.

The second issue is that it would create a complicated, multi-front war waged by untested troops. The Russians have not fought a multi-divisional battle like this since World War II. Their military is competent, but none of their commanders have commanded this type of battle. War games and maneuvers are valuable, but an untested force under fire for the first time needs a very sophisticated command structure. The Russians won’t know if they have one until they try it.

The third issue is the Americans, who will probably not attempt to block the advance with their own troops. Time is of the essence, but imposing friction on an enemy is valuable in itself. The U.S. is in a position to transport Polish forces, for example, to create that friction. (Assuming the Poles are willing.) But if it chose to send its own troops, it would force Russia into full-scale combat on a schedule it was not prepared for. The most important threat from the Americans, however, would be air and missile power. Their targets would be logistic nodes. In armored warfare, which seems to be the plan, the destruction of POL and munitions is the same as destroying tanks. The Russians would need to preempt this by taking out U.S. air and missile installations, very likely on a global scale. Doing this would escalate the war to world war status, and in that situation, the risk for Russia would skyrocket.

The United States recognizes the Russian threat, or at least wants Russia to believe it has recognized it. President Joe Biden’s statements on the matter imply a level of concern that suggests there would be a U.S. intervention if Russia struck. At the very least, the Russians have to factor this possibility into their war planning. The military and political implications of American intervention reduce the urgency of claiming Ukraine as a buffer zone.

Of course, the threat of invasion isn’t exclusive to this strategy. If Russia intends to occupy Ukraine, some variation will be necessary. But an invasion might simply entail taking a piece of Ukraine in the east or the north. The U.S., eager to avoid a war in the middle of Eurasia when the threat is trivial, will likely respond only with sanctions. Russia can stomach that as it threatens further penetration without taking it. This changes the political dynamic if Europe, incapable of mounting a defense, chooses to accommodate Russia.

To be sure, the entire threat might simply be an attempt to test Biden. During the Cold War, testing a new president was a Soviet routine. Doing so now could be seen as a low-risk, high-reward proposition. In fact, there are many counterarguments to my view that a full invasion of Ukraine is too complex and risky to undertake. The Russians cannot afford a defeat in their bid to secure Ukraine in the present geopolitical reality. They have time to move – that is, unless Putin, who hungers to restore the former Soviet border, sees the hand of time moving and is prepared to take a risk for the sake of glory. Perhaps so, but KGB men are trained to be careful. My bet is this is a bluff. But I wouldn’t bet the house on it.

George Friedman is an internationally recognized geopolitical forecaster and strategist on international affairs and the founder and chairman of Geopolitical Futures.

Dr. Friedman is also a New York Times bestselling author. His most recent book, THE STORM BEFORE THE CALM: America’s Discord, the Coming Crisis of the 2020s, and the Triumph Beyond, published February 25, 2020 describes how “the United States periodically reaches a point of crisis in which it appears to be at war with itself, yet after an extended period it reinvents itself, in a form both faithful to its founding and radically different from what it had been.” The decade 2020-2030 is such a period which will bring dramatic upheaval and reshaping of American government, foreign policy, economics, and culture.

No comments:

Post a Comment