Brahma Chellaney

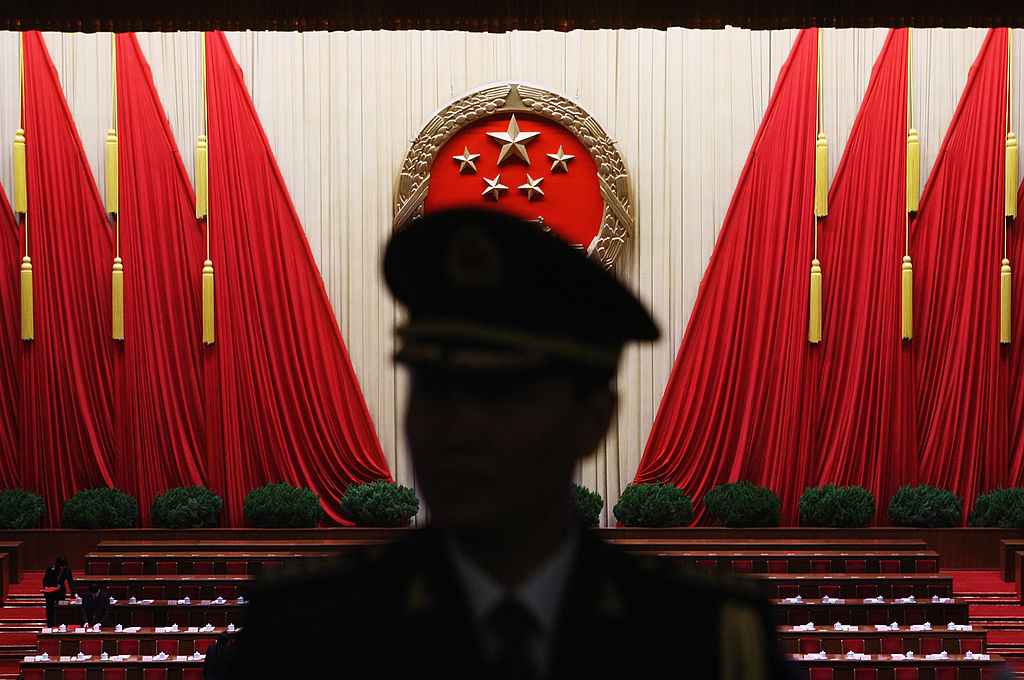

As the world’s largest, strongest and longest-surviving dictatorship, contemporary China lacks the rule of law. Yet it is increasingly using its rubber-stamp parliament to enact domestic legislation asserting territorial claims and rights in international law. In fact, China has become quite adept at waging ‘lawfare’—the misuse and abuse of law for political and strategic ends.

Under ‘commander-in-chief’ Xi Jinping’s bullying leadership, lawfare has developed into a critical component of China’s broader approach to asymmetrical or hybrid warfare. The blurring of the line between war and peace is enshrined in the regime’s official strategy as the ‘three warfares’ (san zhong zhanfa) doctrine. Just as the pen can be mightier than the sword, so too can lawfare, psychological warfare and public-opinion warfare.

Through these methods, Xi is advancing expansionism without firing a shot. Already, China’s bulletless aggression is proving to be a game-changer in Asia. Waging the three warfares in conjunction with military operations has yielded China significant territorial gains.

Within this larger strategy, lawfare is aimed at rewriting rules to animate historical fantasies and legitimise unlawful actions retroactively. For example, China recently enacted a land border law to support its territorial revisionism in the Himalayas. And to advance its expansionism in the South and East China seas, it enacted a coastguard law and new maritime safety regulations earlier this year.

The new laws, authorising the use of force in disputed areas, were established amid rising tensions with neighbouring countries. The border law comes amid a military stalemate in the Himalayas, where more than 100,000 Chinese and Indian troops have been locked in standoffs for nearly 20 months following repeated Chinese incursions into Indian territory.

The coastguard law, by treating disputed waters as China’s, not only violates the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea; it also could trigger armed conflict with Japan or the United States. The land borders law likewise threatens to spark war with India by signalling China’s intent to determine borders unilaterally. It even extends to the Tibet-originating transboundary rivers, where China proclaims a right to divert as much of the shared waters as it wishes.

These recent laws follow the success of the three warfares strategy in redrawing the map of the South China Sea—despite an international arbitral tribunal’s ruling rejecting Chinese territorial claims there—and then swallowing Hong Kong, which had long flourished under democratic institutions as a major global financial centre.

In the South China Sea, through which around a third of global maritime trade passes, Xi’s regime has stepped up lawfare to consolidate Chinese control, turning its contrived historical claims into reality. Last year, while other claimant countries were battling the Covid-19 pandemic, Xi’s government created two new administrative districts to strengthen its claims over the Spratly and Paracel islands and other land features. And in further defiance of international law, China gave Mandarin-language names to 80 islands, reefs, seamounts, shoals and ridges, 55 of which are fully submerged.

The Hong Kong National Security Law, enacted in mid-2020, is a similarly aggressive act of lawfare. Xi has used the law to crush Hong Kong’s pro-democracy movement and rescind the guarantees enshrined in China’s UN-registered treaty with the United Kingdom. The treaty committed China to preserving Hong Kong citizens’ basic rights, freedoms and political self-determination for at least 50 years after regaining sovereignty over the territory.

The strategy’s success in unravelling Hong Kong’s autonomy raises the question of whether China will now enact similar legislation aimed at Taiwan or even invoke its 2005 Anti-Secession Law, which underscored its resolve to bring the island democracy under mainland rule. With China escalating its psychological and information warfare, there’s a real danger that it could move against Taiwan after the Beijing Winter Olympics in February.

Xi’s expansionism hasn’t spared even tiny Bhutan, with a population of just 784,000. Riding roughshod over a 1998 bilateral treaty that obligated China ‘not to resort to unilateral action to alter the status quo of the border,’ the regime has built militarised villages in Bhutan’s northern and western borderlands.

As these examples show, domestic legislation is increasingly providing China with a pretext to flout binding international law, including bilateral and multilateral treaties to which it is a party. With more than one million detainees, Xi’s Muslim gulag in Xinjiang has made a mockery of the 1948 Genocide Convention, to which China acceded in 1983 (with the rider that it doesn’t consider itself bound by Article IX, the clause allowing any party in a dispute to lodge a complaint with the International Court of Justice). And because effective control is the shibboleth of a strong territorial claim in international law, Xi is using new legislation to undergird China’s administration of disputed areas, including with newly implanted residents.

Establishing such facts on the ground is integral to Xi’s territorial aggrandisement. That is why China has taken pains to create artificial islands and administrative districts in the South China Sea, and to pursue a militarised village-building spree in Himalayan borderlands that India, Bhutan and Nepal consider to be within their own national boundaries.

Despite these encroachments, very little international attention has been given to Xi’s lawfare or broader hybrid warfare. The focus on China’s military build-up obscures the fact that the country is quietly expanding its maritime and land boundaries without firing a shot. Given Xi’s overarching goal—to achieve global primacy for China under his leadership—the world’s democracies need to devise a concerted strategy to counter his three warfares.

No comments:

Post a Comment