ANDREW SHENG, XIAO GENG

HONG KONG – Two global struggles – Cold War II and the fight against climate change – are colliding. By agreeing to hold a virtual summit before the end of this year, US President Joe Biden and Chinese President Xi Jinping have signaled that they want to prevent relations from deteriorating to the point that miscalculation could lead to armed conflict – a risk that recent tensions in the Taiwan Strait have highlighted. But Biden and Xi must also ensure that their great-power competition does not hamper cooperation on the existential threat of climate change.

The upcoming United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26) in Glasgow represents a major opportunity for the United States and China to show their commitment to confronting that threat. There is reason for hope. Since 2015, when COP21 delivered the Paris climate agreement, the dangers of global warming have become impossible to ignore, owing to five of the hottest years on record.

Moreover, both the US and China have set ambitious climate goals. Even the corporate sector seems to have woken up to the risks of inaction – and to the opportunities the green transition represents. China alone may have to spend up to $47 trillion to reach its goal of becoming carbon-neutral by 2060. That is a lot of investment that could be directed toward companies that deliver innovative solutions.

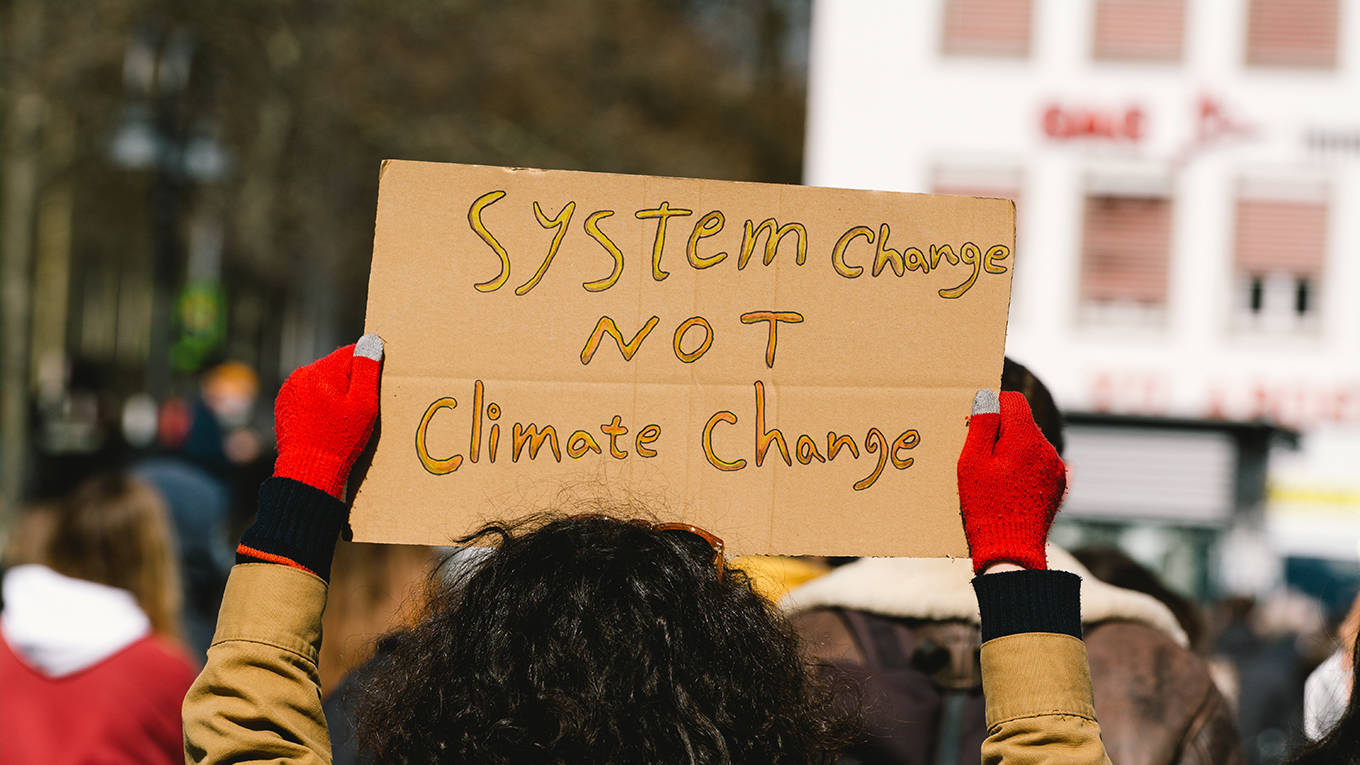

But, as the environmentalist Paul Gilding argued a decade ago, addressing climate change will require not only a large-scale mobilization, on par with that seen during World War II, but also a dramatic shift in mindset. We must replace our “addiction to growth” with an “ethic of sustainability.” Gilding quoted the economist Kenneth Boulding: “Anyone who believes exponential growth can go on forever in a finite world is either a madman or an economist.”

So, average growth will probably need to slow down. At the same time, however, the ratio of consumption to investment must change, because massive resources will be needed to address climate change, as well as meet other social and development goals, such as reducing inequality.

The good news is that global actors, including the International Monetary Fund, increasingly recognize the need for systemic change. And China has quietly stopped targeting GDP growth – a sign that sustainability is now being prioritized over the blind pursuit of higher output.

But, as Gilding recognized, such a systems change will be exceptionally difficult, not least because growth is currently hard-wired into profit plans, debt contracts, consumption decisions, and public policies. The shift from a unipolar to a multipolar world complicates the situation further, because no single power can take responsibility for making tough decisions about global action.

Add to that the zero-sum logic of a new cold war, and systemic change becomes all but impossible. And intensifying tribalism is making that outcome increasingly likely. For example, China views US concerns about its actions in Xinjiang, Tibet, Hong Kong, and Taiwan as nothing more than a bid to undermine its sovereignty. Diverting resources from addressing domestic inequities to pursuing an arms race is a tribalist response.

Beyond fueling great-power competition, tribalism has made rational negotiations harder at the national and local levels. As Amy Chua, Reuben E. Brigety II, and others have observed, tribalism has fractured US politics, fueling social polarization and leading to gridlock on many urgent issues. The gutting of the Biden administration’s $5.4 trillion spending plan is a case in point. When it comes to climate action, gridlock at both the national and global levels is a nightmare scenario.

To understand how to counter tribalism, we must first consider why it has been gaining ground. The post-WWII decolonization push and the post-1989 collapse of the Soviet bloc doubled the number of sovereign states from just over 100 in 1945 to nearly 200 by 2020. Between 1950 and 2018, the world population tripled. And while per capita income more than quadrupled, the gains were not distributed equitably – far from it.

In 2018, the world’s top 2,000 public companies held $189 trillion in assets – 2.2 times world GDP. They had a market value of $56.8 trillion – two-thirds of world GDP. Today, the world’s 26 richest people own as much wealth as the poorest half of the global population. As the wealthiest have gained an increasing share of income, wealth, power, and privilege, middle- and working-class households’ income has stagnated in many places.

Rising inequality and economic insecurity have fueled popular frustration, contributing to the rise of tribalist political movements around the world. Much of the world is now stuck in a vicious cycle of social polarization, environmental degradation, and civil conflict.

Given this, as UN Secretary-General António Guterres put it last year, inequality is the defining issue of our time, and any effort to address climate change must be built on principles of justice. In fact, to overcome tribalist resistance to policy action, countries will have to go further, negotiating – and delivering – a new social contract.

No comments:

Post a Comment