Hilal Khashan

Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman has fundamentally changed the Saudi system of governance established by his grandfather decades ago. In his drive to succeed his ailing father, King Salman, MBS, as he’s commonly known, eliminated the Wahhabi clerical establishment’s position as an influential force in Saudi politics and society. He also canceled the system of checks and balances among the Saudi royals and evicted them from the centers of Saudi power. Through these and other changes, he has imposed a fundamentally different political system that’s indistinguishable from other Arab absolute monarchies and radical republics.

Foundations of Saudi Arabia

Modern Saudi Arabia, also referred to as the Third Saudi State, was established in 1932 by ibn Saud, the father of current King Salman. Ibn Saud built the kingdom based on a balance between the Saudi royals and the custodians of Wahhabism, a sect of Islam that came to dominate Saudi Arabia. He brought peace and stability even to remote parts of the country, delegated different responsibilities to his children and treated the business class with respect and appreciation. After his death in 1953, his children committed to preserving the system of governance established by their late father, even during a turbulent period in the late 1950s and early 1960s. They maintained a system of checks and balances where none of the top princes surrounding the king could dictate Saudi policies. Saudi kings ensured that Cabinet decisions were made by consensus, protecting the unity of the royal family.

As Saudi Arabia’s de facto leader, MBS has no interest in continuing this tradition. He’s proved unwilling to share power with other Saudi royals and has little tolerance for criticism. He gained notoriety for imprisoning intellectuals, activists and female human rights advocates.

MBS was appointed crown prince in 2017 by his father, who removed MBS’ cousin, Muhammad bin Nayef, from the post. Many in the United States viewed MBS as the man who would lead his country into modernity. He met with influential media figures and U.S. policymakers, including President Donald Trump during a visit to the White House in March 2018 that was closely watched by the U.S. media. But his erratic actions have sparked concerns in Washington. In 2017, MBS ordered Lebanese Prime Minister Saad Hariri detained during his visit to Saudi Arabia. Four months before MBS’ trip to the White House, he purged and extorted billions of dollars from leading members of the royal family and the business elite. A year later, Saudi dissident Jamal Khashoggi, who was critical of MBS’ Vision 2030 project and leadership style, was brutally killed in the Saudi Consulate in Istanbul.

MBS knew that prominent members of the Saudi royal family opposed his ascendancy to the throne and viewed him as impulsive and unempathetic. He did not want to face the same fate as his uncle, King Saud, who was dethroned in 1964 by a coalition of senior princes and clergy. Thus, MBS established a personal, extralegal and extrajudicial security apparatus to hunt down Saudi dissidents abroad. Obsessed with the thought that the Saudi royals would deem him unfit to rule, he’s determined to prevent the emergence of another free princes movement, similar to the one established by Prince Talal bin Abdulaziz in 1958. Emerging amid a power struggle between King Saud and Crown Prince Faisal, the movement demanded that Saudi Arabia be transformed into a constitutional parliamentary monarchy. It lost appeal after Faisal became king in 1964 and won the loyalty of the royals and the religious establishment.

A New Saudi State

To guarantee that his own rule isn’t challenged in a similar fashion, MBS has imposed several changes with the support of his father. He shattered the three pillars upon which the kingdom had rested since 1932: adherence to the Wahhabi doctrine, tribal consensus and unity of the Saudi royals. MBS broke the backbone of the Wahhabi establishment by terminating its ability to enforce piety, controlling the content of religious sermons and jailing outspoken clerics. Five months after appointing MBS crown prince, King Salman appointed him as head of the National Anti-Corruption Commission. Immediately afterward, he staged a shakedown in the Ritz-Carlton hotel in Riyadh, where he purged 11 princes, including the minister of the powerful National Guard, and some 400 senior government officials and prominent businesspeople, whom he accused of financial corruption and money laundering.

The move had two objectives: to punish the princes who voted against designating him crown prince and to gain control over a sizable amount of the national wealth. It sent a forceful message to the Saudi royals to toe the line or face arrest, impoverishment and humiliation. MBS admitted to seizing $107 billion from the detainees. It doesn’t matter if he kept the funds for himself or deposited them in the national treasury; since the kingdom’s founding, there has never been a distinction between the treasury and the monarch, who could withdraw money at will from the finance department. Importantly, however, other members of the royal family have been cut off from accessing public assets. (Though Saudi royals do not disclose their finances, MBS is by all accounts a multibillionaire. He purchased Leonardo da Vinci’s painting, the Salvator Mundi, for $450 million and a superyacht for $550 million.)

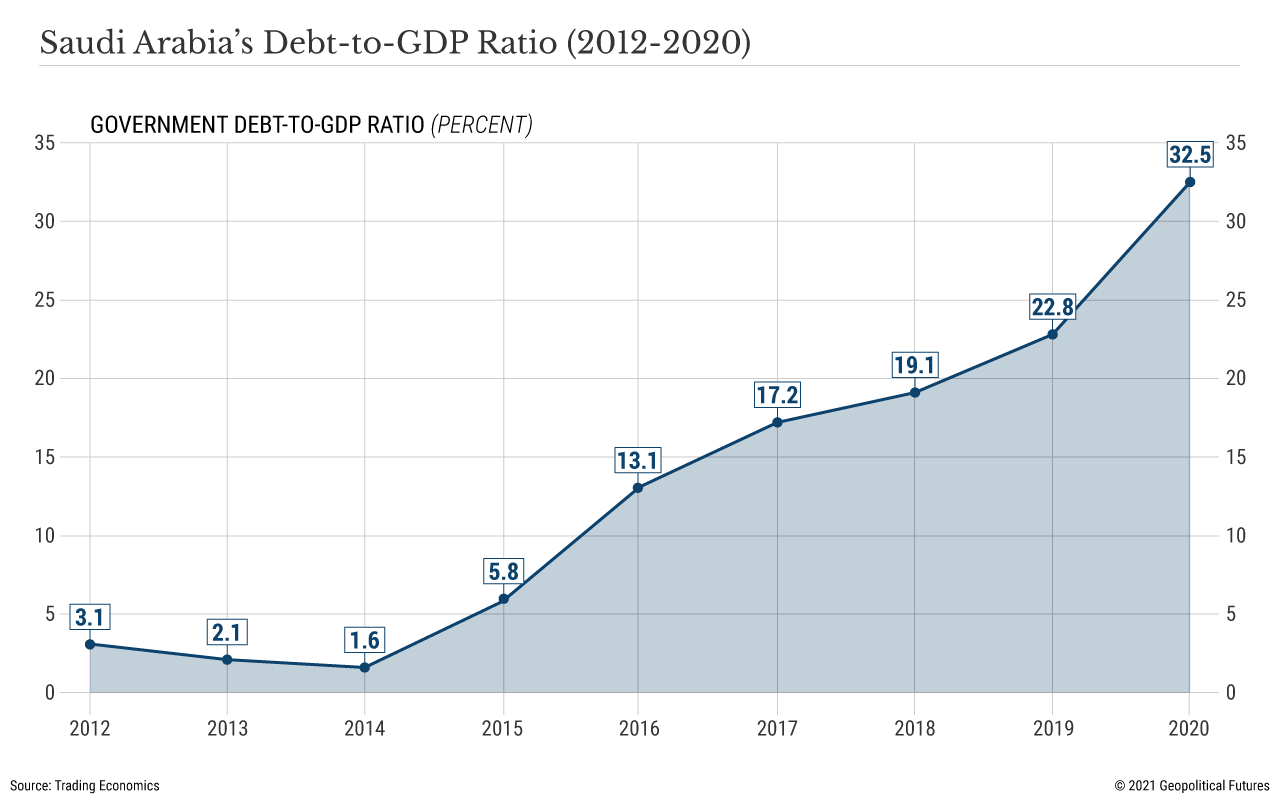

Understandably, his social policies, including eliminating the austere Wahhabi code of conduct, made MBS popular among Saudi youth and women. Still, their support is contingent upon the success of his economic modernization plans. The trap of economic development is that it inevitably leads to rising demands for political participation, though MBS is highly unlikely to tolerate such calls. Many also doubt the future of his Neom megaproject, a $500 billion plan to transform Saudi Arabia into a modern country. Five years since he announced Vision 2030, another program to make Saudi Arabia a world-class economic power, non-oil revenues still account for only a small portion of the country’s gross domestic product. He also centralized all essential state functions in his hands to dominate Saudi Arabia’s political, economic, security and military decision-making.

MBS promised more social freedoms. He relaxed the dress code for women, no longer requiring them to cover their faces, and invited foreign bands and singers to perform in Saudi Arabia. He proscribed the activities of the religiously austere Commission for the Promotion of Virtue and Prevention of Vice. He also established the General Entertainment Authority to demonstrate his willingness to part from the country’s traditional past. But the sudden shift raised eyebrows. It eroded the people’s traditional value system without equipping them with the tools of behavioral change.

Saudi Arabia has lost control of the Gulf Cooperation Council, with the United Arab Emirates now its main rival in regional politics. Abu Dhabi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed, a trusted U.S. ally, is now wielding influence over Saudi foreign policy, dragging Riyadh into the war in Yemen and convincing MBS in 2017 to impose a blockade on Qatar for allegedly supporting terrorism and meddling in the region’s affairs. The Saudis lifted the siege after Joe Biden won the 2020 U.S. presidential race but achieved nothing from the embargo, which only strengthened Qatar’s relations with Tehran and prompted it to authorize Turkey to build a military base on its territory.

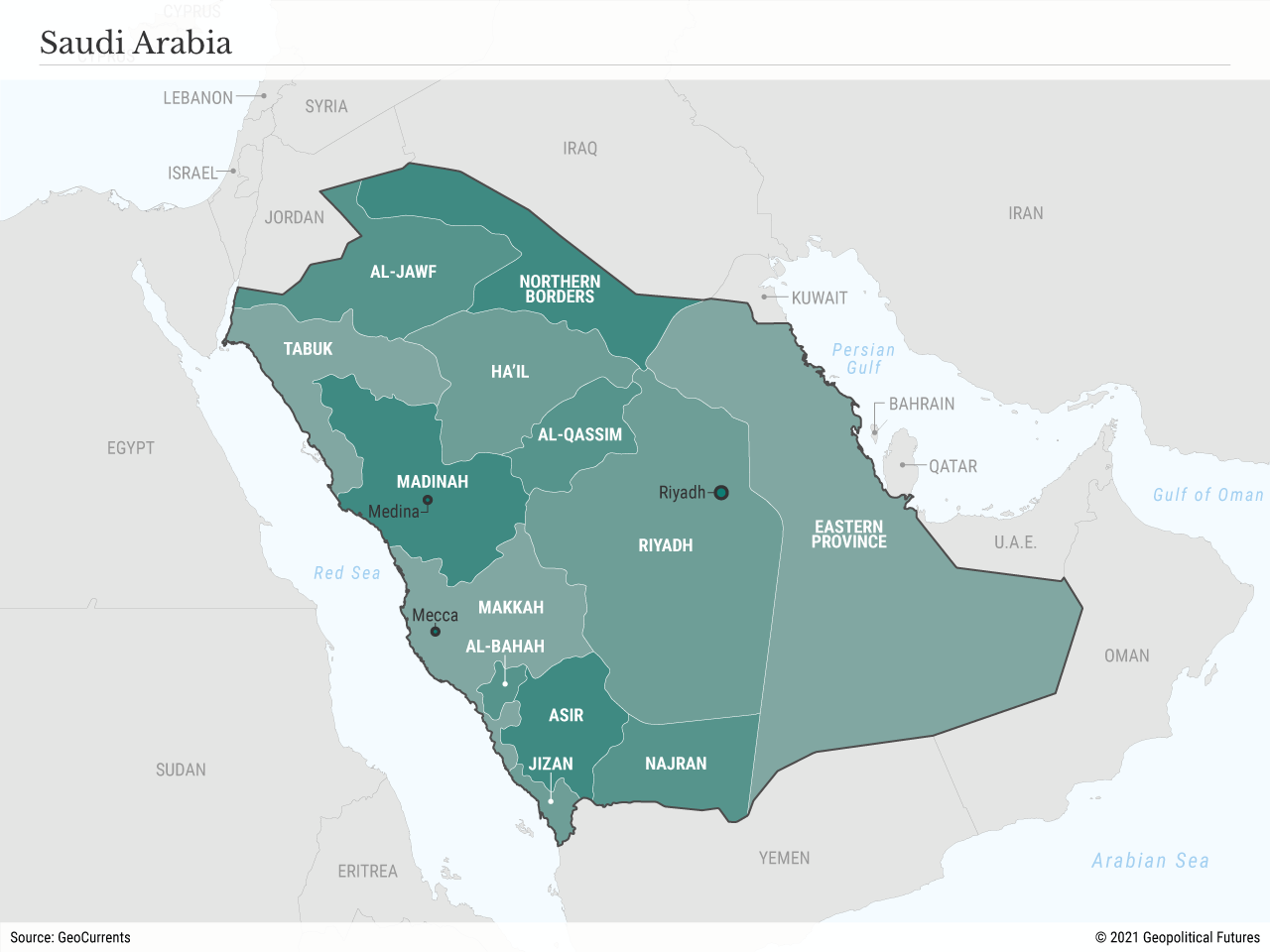

MBS decided to join the Yemeni war in 2015 against the advice of his Egyptian and Pakistani allies. He knew that the Houthi rebels had dealt the Saudi army a heavy blow in 2009 when Saudi troops ventured into Houthi territory, occupying several villages and mountaintops in Jizan. But MBS went to war with the Houthis anyway, hoping to score a quick victory. Nearly seven years later, the Saudis are losing the war and have no plan to withdraw.

What the Future Holds

MBS is using draconian measures to build the fourth Saudi state. But he looks likely to become its first and last monarch. Squeezed for funds, the government curtailed its generous welfare system after more than half a century of pampering the Saudi people. The speed with which changes have been introduced has shocked many Saudis, and an increasing number of citizens are becoming disillusioned with his often erratic decisions.

Saudi Arabia is a heterogeneous tribal country. It includes the Najd region, a Wahhabi stronghold that accounts for less than one-third of the Saudi population; the heavily Shiite Eastern Province; Hejaz, which includes Islam’s two holiest mosques, Mecca and Medina; the Asir region south of Hejaz; Najran and Jizan next to Yemen’s Saada mountains; and Northern Borders province, which has traditional links to southern Iraq and Jordan. Material abundance, political stability and the central government’s coercive capabilities held Saudi Arabia’s diverse population together. Cracks in the system under volatile political leadership have the potential to pull them apart.

No comments:

Post a Comment