Anne Applebaum

The future of democracy may well be decided in a drab office building on the outskirts of Vilnius, alongside a highway crammed with impatient drivers heading out of town.

I met Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya there this spring, in a room that held a conference table, a whiteboard, and not much else. Her team—more than a dozen young journalists, bloggers, vloggers, and activists—was in the process of changing offices. But that wasn’t the only reason the space felt stale and perfunctory. None of them, especially not Tsikhanouskaya, really wanted to be in this ugly building, or in the Lithuanian capital at all. She is there because she probably won the 2020 presidential election in Belarus, and because the Belarusian dictator she probably defeated, Alexander Lukashenko, forced her out of the country immediately afterward. Lithuania offered her asylum. Her husband, Siarhei Tsikhanouski, remains imprisoned in Belarus.

Here is the first thing she said to me: “My story is a little bit different from other people.” This is what she tells everyone—that hers was not the typical life of a dissident or budding politician. Before the spring of 2020, she didn’t have much time for television or newspapers. She has two children, one of whom was born deaf. On an ordinary day, she would take them to kindergarten, to the doctor, to the park.

Then her husband bought a house and ran into the concrete wall of Belarusian bureaucracy and corruption. Exasperated, he started making videos about his experiences, and those of others. These videos yielded a YouTube channel; the channel attracted thousands of followers. He went around the country, recording the frustrations of his fellow citizens, driving a car with the phrase “Real News” plastered on the side. Siarhei Tsikhanouski held up a mirror to his society. People saw themselves in that mirror and responded with the kind of enthusiasm that opposition politicians had found hard to create in Belarus.

“At the beginning it was really difficult because people were afraid,” Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya told me. “But step-by-step, slowly, they realized that Siarhei isn’t afraid.” He wasn’t afraid to speak the truth as he saw it; his absence of fear inspired others. He decided to run for president. The regime, recognizing the power of Siarhei’s mirror, would not allow him to register his candidacy, just as it had not allowed him to register the ownership of his house. It ended his campaign and arrested him.

Tsikhanouskaya ran in his place, with no motive other than “to show my love for him.” The police and bureaucrats let her. Because what harm could she do, this simple housewife, this woman with no political experience? And so, in July 2020, she registered as a candidate. Unlike her husband, she was afraid. She woke up “so scared” every morning, she told me, and sometimes she stayed scared all day long. But she kept going. Which was, though she doesn’t say so, incredibly brave. “You feel this responsibility, you wake up with this pain for those people who are in jail, you go to bed with the same feeling.”

Unexpectedly, Tsikhanouskaya was a success—not despite her inexperience, but because of it. Her campaign became a campaign about ordinary people standing up to the regime. Two other prominent opposition politicians endorsed her after their own campaigns were blocked, and when the wife of one of them and the female campaign manager of the other were photographed alongside Tsikhanouskaya, her campaign became something more: a campaign about ordinary women—women who had been neglected, women who had no voice, even just women who loved their husbands. In return, the regime targeted all three of these women. Tsikhanouskaya received an anonymous threat: Her children would be “sent to an orphanage.” She dispatched them with her mother abroad, to Vilnius, and kept campaigning.Democratic revolutions are contagious. If you can stamp them out in one country, you might prevent them from starting in others.

On August 9, election officials announced that Lukashenko had won 80 percent of the vote, a number nobody believed. The internet was cut off, and Tsikhanouskaya was detained by police and then forced out of the country. Mass demonstrations unfolded across Belarus. These were both a spontaneous outburst of feeling—a popular response to the stolen election—and a carefully coordinated project run by young people, some based in Warsaw, who had been experimenting with social media and new forms of communication for several years. For a brief, tantalizing moment, it looked like this democratic uprising might prevail. Belarusians shared a sense of national unity they had never felt before. The regime immediately pushed back, with real brutality. Yet the mood at the protests was generally happy, optimistic; people literally danced in the streets. In a country of fewer than 10 million, up to 1.5 million people would come out in a single day, among them pensioners, villagers, factory workers, and even, in a few places, members of the police and the security services, some of whom removed insignia from their uniforms or threw them in the garbage.

Tsikhanouskaya says she and many others naively believed that under this pressure, the dictator would just give up. “We thought he would understand that we are against him,” she told me. “That people don’t want to live under his dictatorship, that he lost the elections.” They had no other plan.

At first, Lukashenko seemed to have no plan either. But his neighbors did. On August 18, a plane belonging to the FSB, the Russian security services, flew from Moscow to Minsk. Soon after that, Lukashenko’s tactics underwent a dramatic change. Stephen Biegun, who was the U.S. deputy secretary of state at the time, describes the change as a shift to “more sophisticated, more controlled ways to repress the population.” Belarus became a textbook example of what the journalist William J. Dobson has called “the dictator’s learning curve”: Techniques that had been used successfully in the past to repress crowds in Russia were seamlessly transferred to Belarus, along with personnel who understood how to deploy them. Russian television journalists arrived to replace the Belarusian journalists who had gone on strike, and immediately stepped up the campaign to portray the demonstrations as the work of Americans and other foreign “enemies.” Russian police appear to have supplemented their Belarusian colleagues, or at least given them advice, and a policy of selective arrests began. As Vladimir Putin figured out a long time ago, mass arrests are unnecessary if you can jail, torture, or possibly murder just a few key people. The rest will be frightened into staying home. Eventually they will become apathetic, because they believe nothing can change.

The Lukashenko rescue package, reminiscent of the one Putin had designed for Bashar al-Assad in Syria six years earlier, contained economic elements too. Russian companies offered markets for Belarusian products that had been banned by the democratic West—for example, smuggling Belarusian cigarettes into the European Union. Some of this was possible because the two countries share a language. (Though roughly a third to half of the country speaks Belarusian, most public business in Belarus is conducted in Russian.) But this close cooperation was also possible because Lukashenko and Putin, though they famously dislike each other, share a common way of seeing the world. Both believe that their personal survival is more important than the well-being of their people. Both believe that a change of regime would result in their death, imprisonment, or exile.

Both also learned lessons from the Arab Spring, as well as from the more distant memory of 1989, when Communist dictatorships fell like dominoes: Democratic revolutions are contagious. If you can stamp them out in one country, you might prevent them from starting in others. The anti-corruption, prodemocracy demonstrations of 2014 in Ukraine, which resulted in the overthrow of President Viktor Yanukovych’s government, reinforced this fear of democratic contagion. Putin was enraged by those protests, not least because of the precedent they set. After all, if Ukrainians could get rid of their corrupt dictator, why wouldn’t Russians want to do the same?

Lukashenko gladly accepted Russian help, turned against his people, and transformed himself from an autocratic, patriarchal grandfather—a kind of national collective-farm boss—into a tyrant who revels in cruelty. Reassured by Putin’s support, he began breaking new ground. Not just selective arrests—a year later, human-rights activists say that more than 800 political prisoners remain in jail—but torture. Not just torture but rape. Not just torture and rape but kidnapping and, quite possibly, murder.

Lukashenko’s sneering defiance of the rule of law—he issues stony-faced denials of the existence of political repression in his country—and of anything resembling decency spread beyond his borders. In May 2021, Belarusian air traffic control forced an Irish-owned Ryanair passenger plane to land in Minsk so that one of the passengers, Roman Protasevich, a young dissident living in exile, could be arrested; he later made public confessions on television that appeared to be coerced. In August, another young dissident living in exile, Vitaly Shishov, was found hanged in a Kyiv park. At about the same time, Lukashenko’s regime set out to destabilize its EU neighbors by forcing streams of refugees across their borders: Belarus lured Afghan and Iraqi refugees to Minsk with a proffer of tourist visas, then escorted them to the borders of Lithuania, Latvia, and Poland and forced them at gunpoint to cross, illegally.

Lukashenko began to act, in other words, as if he were untouchable, both at home and abroad. He began breaking not only the laws and customs of his own country, but also the laws and customs of other countries, and of the international community—laws regarding air traffic control, homicide, borders. Exiles flowed out of the country; Tsikhanouskaya’s team scrambled to book hotel rooms or Airbnbs in Vilnius, to find means of support, to learn new languages. Tsikhanouskaya herself had to make another, even more difficult transition—from people’s-choice candidate to sophisticated diplomat. This time her inexperience initially worked against her. At first, she thought that if she could just speak with Angela Merkel or Emmanuel Macron, one of them could fix the problem. “I was sure they are so powerful that they can call Lukashenko and say, ‘Stop! How dare you?’ ” she told me. But they could not.

So she tried to talk as foreign leaders did, to speak in sophisticated political language. That didn’t work either. The experience was demoralizing: “It’s very difficult sometimes to talk about your people, about their sufferings, and see the emptiness in the eyes of those you are talking to.” She began using the plain English that she had learned in school, in order to convey plain things. “I started to tell stories that would touch their hearts. I tried to make them feel just a little of the pain that Belarusians feel.” Now she tells anyone who will listen exactly what she told me: I am an ordinary person, a housewife, a mother of two children, and I am in politics because other ordinary people are being beaten naked in prison cells. What she wants is sanctions, democratic unity, pressure on the regime—anything that will raise the cost for Lukashenko to stay in power, for Russia to keep him in power. Anything that might induce the business and security elites in Belarus to abandon him. Anything that might persuade China and Iran to keep out.

To her surprise, Tsikhanouskaya became, for the second time, a runaway success. She charmed Merkel and Macron, and the diplomats of multiple countries. In July, she met President Joe Biden, who subsequently broadened American sanctions on Belarus to include major companies in several industries (tobacco, potash, construction) and their executives. The EU had already banned a range of people, companies, and technologies from Belarus; after the Ryanair kidnapping, the EU and the U.K. banned the Belarusian national airline as well. What was once a booming trade between Belarus and Europe has been reduced to a trickle. Tsikhanouskaya inspires people to make sacrifices of their own. The Lithuanian foreign minister, Gabrielius Landsbergis, told me that his country was proud to host her, even if it meant trouble on the border. “If we’re not free to invite other free people into our country because it’s somehow not safe, then the question is, can we consider ourselves free?”

Tsikhanouskaya has acquired many other supporters and admirers. She has not only the talented young activists in Vilnius, but colleagues in Poland and Ukraine as well. She promotes values that unite millions of her compatriots, including pensioners like Nina Bahinskaya, a great-grandmother who has been filmed shouting at the police, and ordinary working people like Siarhei Hardziyevich, a 50-year-old journalist from a provincial town, Drahichyn, who was convicted of “insulting the president.” On her side she also has the friends and relatives of the hundreds of political prisoners who, like her own husband, are paying a high price just because they want to live in a country with free elections.

Most of all, though, Tsikhanouskaya has on her side the combined narrative power of what we used to call the free world. She has the language of human rights, democracy, and justice. She has the NGOs and human-rights organizations that work inside the United Nations and other international institutions to put pressure on autocratic regimes. She has the support of people around the world who still fervently believe that politics can be made more civilized, more rational, more humane, who can see in her an authentic representative of that cause.

But will that be enough? A lot depends on the answer.

Michael Houtz

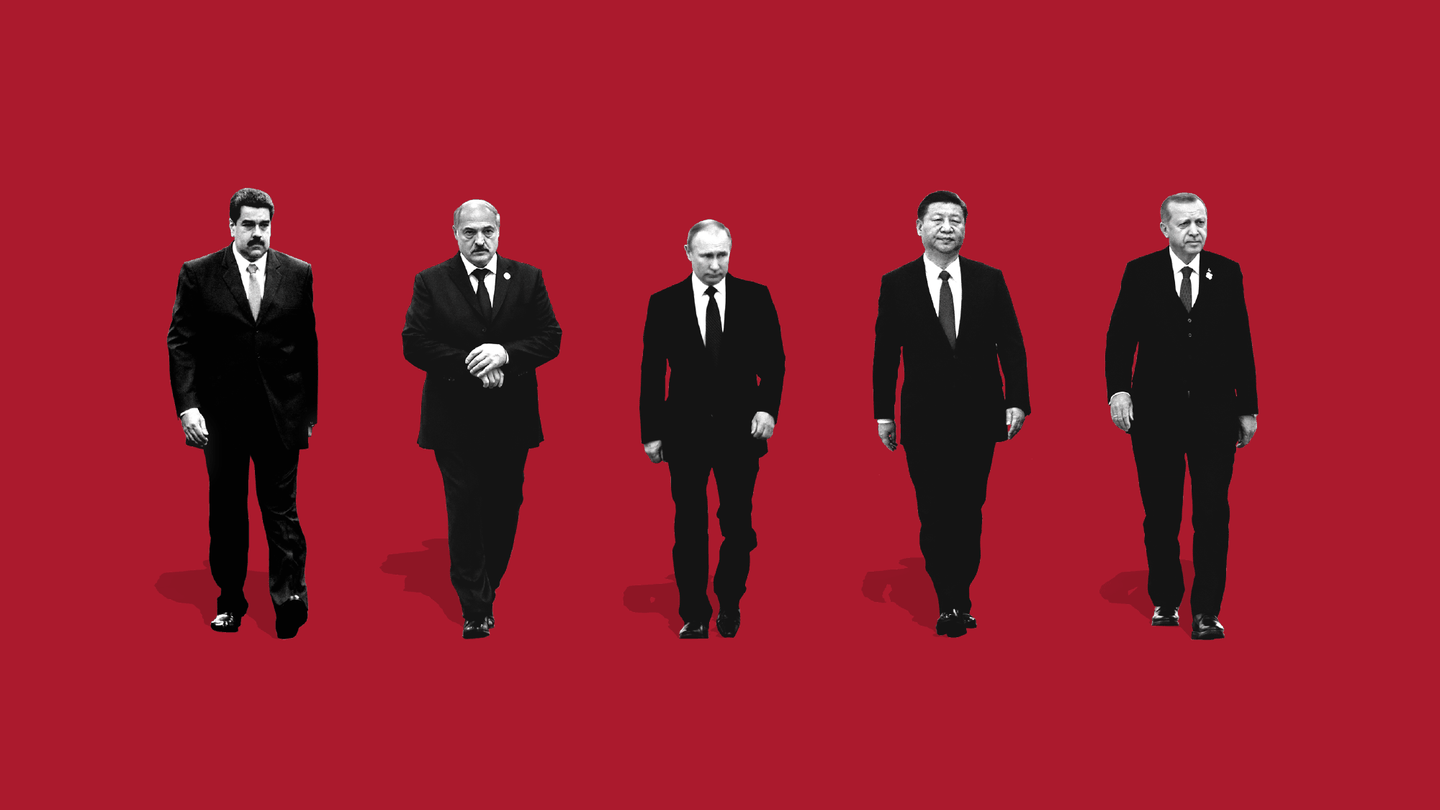

All of us have in our minds a cartoon image of what an autocratic state looks like. There is a bad man at the top. He controls the police. The police threaten the people with violence. There are evil collaborators, and maybe some brave dissidents.

But in the 21st century, that cartoon bears little resemblance to reality. Nowadays, autocracies are run not by one bad guy, but by sophisticated networks composed of kleptocratic financial structures, security services (military, police, paramilitary groups, surveillance), and professional propagandists. The members of these networks are connected not only within a given country, but among many countries. The corrupt, state-controlled companies in one dictatorship do business with corrupt, state-controlled companies in another. The police in one country can arm, equip, and train the police in another. The propagandists share resources—the troll farms that promote one dictator’s propaganda can also be used to promote the propaganda of another—and themes, pounding home the same messages about the weakness of democracy and the evil of America.

This is not to say that there is some supersecret room where bad guys meet, as in a James Bond movie. Nor does the new autocratic alliance have a unifying ideology. Among modern autocrats are people who call themselves communists, nationalists, and theocrats. No one country leads this group. Washington likes to talk about Chinese influence, but what really bonds the members of this club is a common desire to preserve and enhance their personal power and wealth. Unlike military or political alliances from other times and places, the members of this group don’t operate like a bloc, but rather like an agglomeration of companies—call it Autocracy Inc. Their links are cemented not by ideals but by deals—deals designed to take the edge off Western economic boycotts, or to make them personally rich—which is why they can operate across geographical and historical lines.

Thus in theory, Belarus is an international pariah—Belarusian planes cannot land in Europe, many Belarusian goods cannot be sold in the U.S., Belarus’s shocking brutality has been criticized by many international institutions. But in practice, the country remains a respected member of Autocracy Inc. Despite Lukashenko’s flagrant flouting of international norms, despite his reaching across borders to break laws, Belarus remains the site of one of China’s largest overseas development projects. Iran has expanded its relationship with Belarus over the past year. Cuban officials have expressed their solidarity with Lukashenko at the UN, calling for an end to “foreign interference” in the country’s affairs.

In theory, Venezuela, too, is an international pariah. Since 2008, the U.S. has repeatedly added more Venezuelans to personal-sanctions lists; since 2019, U.S. citizens and companies have been forbidden to do any business there. Canada, the EU, and many of Venezuela’s South American neighbors maintain sanctions on the country. And yet Nicolás Maduro’s regime receives loans as well as oil investment from Russia and China. Turkey facilitates the illicit Venezuelan gold trade. Cuba has long provided security advisers, as well as security technology, to the country’s rulers. The international narcotics trade keeps individual members of the regime well supplied with designer shoes and handbags. Leopoldo López, a onetime star of the opposition now living in exile in Spain, has observed that although Maduro’s opponents have received some foreign assistance, it’s “nothing comparable with what Maduro has received.”

Like the Belarusian opposition, the Venezuelan opposition has charismatic leaders and dedicated grassroots activists who have persuaded millions of people to go out into the streets and protest. If their only enemy was the corrupt, bankrupt Venezuelan regime, they might win. But Lopez and his fellow dissidents are in fact fighting multiple autocrats, in multiple countries. Like so many other ordinary people propelled into politics by the experience of injustice—like Sviatlana and Siarhei Tsikhanouski in Belarus, like the leaders of the extraordinary Hong Kong protest movement, like the Cubans and the Iranians and the Burmese pushing for democracy in their countries—they are fighting against people who control state companies and can make investment decisions worth billions of dollars for purely political reasons. They are fighting against people who can buy sophisticated surveillance technology from China or bots from St. Petersburg. Above all, they are fighting against people who have inured themselves to the feelings and opinions of their countrymen, as well as the feelings and opinions of everybody else. Because Autocracy Inc. grants its members not only money and security, but also something less tangible and yet just as important: impunity.How have modern autocrats achieved such impunity? In part by persuading so many other people in so many other countries to play along.

The leaders of the Soviet Union, the most powerful autocracy in the second half of the 20th century, cared deeply about how they were perceived around the world. They vigorously promoted the superiority of their political system and they objected when it was criticized. When the Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev famously brandished his shoe at a meeting of the UN General Assembly in 1960, it was because a Filipino delegate had expressed sympathy for “the peoples of Eastern Europe and elsewhere which have been deprived of the free exercise of their civil and political rights.”

Today, the most brutal members of Autocracy Inc. don’t much care if their countries are criticized, or by whom. The leaders of Myanmar don’t really have any ideology beyond nationalism, self-enrichment, and the desire to remain in power. The leaders of Iran confidently discount the views of Western infidels. The leaders of Cuba and Venezuela dismiss the statements of foreigners on the grounds that they are “imperialists.” The leaders of China have spent a decade disputing the human-rights language long used by international institutions, successfully convincing many people around the world that these “Western” concepts don’t apply to them. Russia has gone beyond merely ignoring foreign criticism to outright mocking it. After the Russian dissident Alexei Navalny was arrested earlier this year, Amnesty International designated him a “prisoner of conscience,” a venerable term that the human-rights organization has been using since the 1960s. Russian social-media trolls immediately mounted a campaign designed to draw Amnesty’s attention to 15-year-old statements by Navalny that seemed to break the group’s rules on offensive language. Amnesty took the bait and removed the title. Then, when Amnesty officials realized they’d been manipulated by trolls, they restored it. Russian state media cackled derisively. It was not a good moment for the human-rights movement.

Impervious to international criticism, modern autocrats are using aggressive tactics to push back against mass protest and widespread discontent. Putin was unembarrassed to stage “elections” earlier this year in which some 9 million people were barred from being candidates, the progovernment party received five times more television coverage than all the other parties put together, television clips of officials stealing votes circulated online, and vote counts were mysteriously altered. The Burmese junta is unashamed to have murdered hundreds of protesters, including young teenagers, on the streets of Yangon. The Chinese government boasts about its destruction of the popular democracy movement in Hong Kong.

At the extremes, this kind of contempt can devolve into what the international democracy activist Srdja Popovic calls the “Maduro model” of governance, which may be what Lukashenko is preparing for in Belarus. Autocrats who adopt it are “willing to pay the price of becoming a totally failed country, to see their country enter the category of failed states,” accepting economic collapse, isolation, and mass poverty if that’s what it takes to stay in power. Assad has applied the Maduro model in Syria. And it seems to be what the Taliban leadership had in mind this summer when they occupied Kabul and immediately began arresting and murdering Afghan officials and civilians. Financial collapse was looming, but they didn’t care. As one Western official working in the region told the Financial Times, “They assume that any money that the west doesn’t give them will be replaced by China, Pakistan, Russia and Saudi Arabia.” And if the money doesn’t come, so what? Their goal is not a flourishing, prosperous Afghanistan, but an Afghanistan where they are in charge.

The widespread adoption of the Maduro model helps explain why Western statements at the time of Kabul’s fall sounded so pathetic. The EU’s foreign-policy chief expressed “deep concern about reports of serious human rights violations” and called for “meaningful negotiations based on democracy, the rule of law and constitutional rule”—as if the Taliban was interested in any of that. Whether it was “deep concern,” “sincere concern,” or “profound concern,” whether it was expressed on behalf of Europe or the Holy See, none of it mattered: Statements like that mean nothing to the Taliban, the Cuban security services, or the Russian FSB. Their goals are money and personal power. They are not concerned—deeply, sincerely, profoundly, or otherwise—about the happiness or well-being of their fellow citizens, let alone the views of anyone else.

How have modern autocrats achieved such impunity? In part by persuading so many other people in so many other countries to play along. Some of those people, and some of those countries, might surprise you.

Michael Houtz

If the stories told by the young dissidents in Vilnius make you angry, the stories told by the Uyghurs of Istanbul will haunt your dreams.

A few months ago, in a hot, airless apartment over a dress shop, I met Kalbinur Tursun. She was dressed in a dark-green gown with ruffled sleeves. Her face, framed by a tightly drawn headscarf, resembled that of a saint in a medieval triptych. Her small daughter, in Mickey Mouse leggings, played with an electronic tablet while we spoke.

Tursun is a Uyghur, a member of China’s predominantly Muslim Chinese minority, born in the territory that the Chinese call Xinjiang and that many Uyghurs know as East Turkestan. Tursun had six children—too many in a country where there are strict rules limiting births. Also, she wanted to raise them as Muslims; that, too, was a problem in China. When she became pregnant again, she feared being harassed by police, as women with more than two children often are. She and her husband decided to move to Turkey. They got passports for themselves and for their youngest child, but were told the other passports would take longer. Because of her pregnancy, the three of them came to Istanbul anyway; after she and her daughter were settled, her husband returned for the rest of the family. Then he disappeared.

That was five years ago. Tursun has not spoken with her husband since. In July 2017, she spoke with her sister, who promised to take care of her remaining children. Then they lost contact. A year after that, Tursun came across a video being passed around on WhatsApp. Shot at what appeared to be a Chinese orphanage, it showed Uyghur children, heads shaved and all dressed alike, learning to speak Chinese. One of the children was her daughter Ayshe.

Tursun showed me the video of her daughter. She also showed me a picture of her husband standing in an Istanbul mosque. She cannot speak to either one of them, or to any of the rest of her children in China. She has no way to know what they are thinking. They might not know she has searched for them. They might believe she has abandoned them on purpose. They might have forgotten she exists. Meanwhile, time is passing. The child in the Mickey Mouse leggings, who sang to herself while we talked, is the one born in Turkey. She has never met her father, or her brothers and sisters in China. But she knows something is very wrong; when Tursun fell silent for a moment, overcome with emotion, the girl put down her tablet and put her arms around her mother’s neck.

Sinister though it sounds, Tursun’s story is not unique. The translator for my conversation with Tursun was Nursiman Abdureshid. She is also a Uyghur, also from Xinjiang, also married, also with a daughter, also now living in Istanbul. Abdureshid came to Turkey as a student, convinced that she had the backing of the Chinese state. A graduate of Shanghai University of Finance and Economics, she had studied business administration, learned excellent Turkish and English, made ethnic-Chinese friends. She had never thought of herself as a rebel or a dissident. Why would she have? She was a Chinese success story.

Abdureshid’s break with her old life came in June 2017, when, after an ordinary conversation with her family back in China, they stopped answering her calls. She texted and got no response. Weeks passed. After many months, she contacted the consulate in Istanbul—she asked a Turkish friend to call for her—and officials there finally told her the truth: Her father, mother, and younger brother were in prison camps, each for “preparing to commit terrorist activities.”

A similar charge was thrown at Jevlan Shirmemet, another Uyghur student in Istanbul. Like Abdureshid, he realized something was wrong when his mother and other relatives stopped responding to texts. Then they blocked him on WeChat, the Chinese messaging app. Nearly two years later, he learned that they were in prison camps. Chinese diplomats accused him of having “anti-Chinese” contacts in Egypt, as well. Shirmemet told them he had never been to Egypt. Prove it, they responded, then added: Cooperate with us, tell us who all of your friends are, list every place you have ever been, become an informer. He refused and—though not temperamentally inclined to be a dissident either—decided to speak out on social media instead. “I had remained silent, but my silence didn’t protect my family,” he told me.

Turkey is home to some 50,000 exiled Uyghurs, and there are dozens, hundreds, perhaps thousands of such stories there. İlyas Doğan, a Turkish lawyer who has represented some of the Uyghurs, told me that, until 2017, very few of them were politically active. But after friends and relatives began disappearing into “reeducation camps”—concentration camps, in fact—set up by the Chinese state, the situation changed.

Tursun and a group of other women who had lost children staged a protest walk from Istanbul to Ankara, a distance of more than 270 miles, and then stood in front of a UN building, demanding to be heard. Abdureshid spoke at the conference of one of the Turkish opposition parties. “I haven’t heard my mother’s voice for four years,” she told the audience. A video of the speech went viral; when we had lunch at a restaurant in a Uyghur neighborhood, a waiter recognized her and thanked her for it.

In another era—in a world with a different geopolitical configuration, at a time when the language of human rights had not been so comprehensively undermined—these dissidents would have plenty of official sympathy in Turkey, a nation that is singularly linked to the Uyghur community by ties of religion, ethnicity, and language. In 2009, even before the concentration camps were opened, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, who was then the Turkish prime minister, called the Chinese repression of the Uyghurs a “genocide.” In 2012, he brought businessmen with him to Xinjiang and promised to invest in Uyghur businesses there. He did this because it was popular. To the extent that ordinary Turks know what is happening to their Uyghur cousins, they sympathize.

Yet since then, Erdoğan—who became president in 2014—has himself turned against the rule of law, independent media, and independent courts at home. As he has become openly hostile to former European and NATO allies, and as he has arrested and jailed his own dissidents, Erdoğan’s interest in Chinese friendship, investment, and technology has increased, along with his willingness to echo Chinese propaganda. On the 100th anniversary of the Chinese Communist Party, his party’s flagship newspaper published a long, solemn article—which was in fact sponsored content—beneath the headline “The Chinese Communist Party’s 100 Years of Glorious History and the Secrets to Its Success.” Alongside these changes, government policy toward the Uyghurs has shifted too.

In recent years, the Turkish government has surveilled and detained Uyghurs on bogus terrorism charges, and deported some, including four who were sent to Tajikistan and then immediately turned over to China in 2019. In Istanbul, I met one Uyghur—he preferred to remain anonymous—who had spent time in a Turkish detention center, along with some of his family, following what he said were bogus charges of “terrorism.” The presence of pro-Chinese forces in Turkish media, politics, and business has been growing, and lately they are keen to belittle the Uyghurs. Curiously, Abdureshid’s speech was cut from the public-television broadcast of the opposition-party conference she attended. After it started circulating on social media, she was publicly attacked by a Turkish politician, Doğu Perinçek, a former Maoist who is pro-Chinese, anti-Western, and quite influential. After Perinçek described her as a “terrorist” on television, a wave of online attacks followed.

The atmosphere worsened in late 2020, when a delayed Chinese shipment of COVID-19 vaccines coincided with Beijing’s pressure on Turkey to sign an extradition treaty that would have made deportation of Uyghurs even easier. After opposition parties objected, both the Turkish and Chinese governments denied that delivery of the vaccine shipment was in any way conditioned on deporting Uyghurs, but the timing remains suspicious. Several Uyghurs in Istanbul told me that corrupt elements in the Turkish police work directly with the Chinese already. They have no proof, and Doğan, the Turkish lawyer, told me that he doubts this is the case; still, he thinks that, despite all of the old cultural ties, the Turkish government might not mind if the Uyghurs stopped protesting or quietly moved elsewhere.

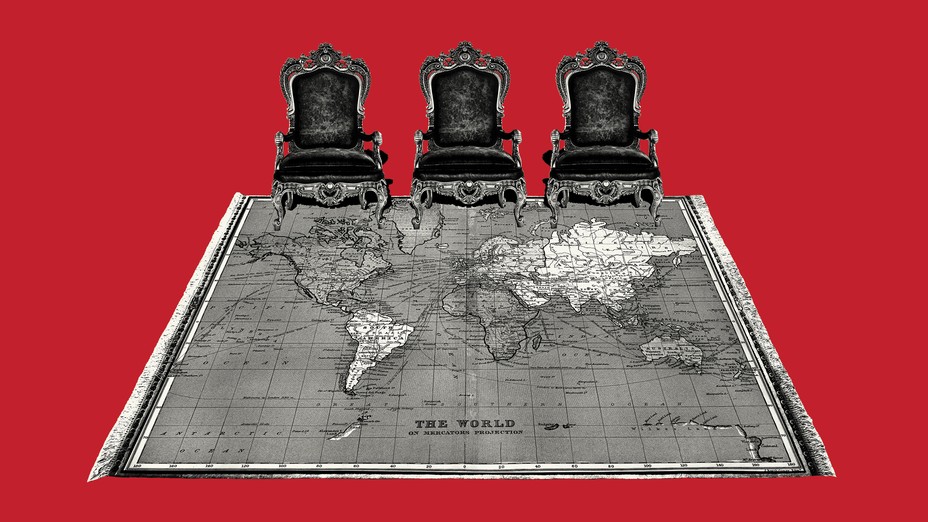

For the moment, the Uyghurs in Turkey are still protected by what remains of democracy there: the opposition parties, some of the media, public opinion. A government that faces democratic elections, even skewed ones, must still take these things into account. In countries where opposition, media, and public opinion matter less, the balance is different. You can see this even in Muslim countries, which might be expected to object to the oppression of other Muslims. Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan has stated baldly that “we accept the Chinese version” of the Chinese-Uyghur dispute. The Saudis, the Emiratis, and the Egyptians have all allegedly arrested, detained, and deported Uyghurs without much discussion. Not coincidentally, these are all countries that seek good economic relations with China, and that have purchased Chinese surveillance technology. For autocrats and would-be autocrats around the world, the Chinese offer a package that looks something like this: Agree to follow China’s lead on Hong Kong, Tibet, the Uyghurs, and human rights more broadly. Buy Chinese surveillance equipment. Accept massive Chinese investment (preferably into companies you personally control, or that at least pay you kickbacks). Then sit back and relax, knowing that however bad your image becomes in the eyes of the international human-rights community, you and your friends will remain in power.

Michael Houtz

Michael HoutzAnd how different are we? We Americans? We Europeans? Are we so sure that our institutions, our political parties, our media could never be manipulated in the same way? In the spring of 2016, I helped publish a report on the Russian use of disinformation in Central and Eastern Europe—the now familiar Russian efforts to manipulate political conversations in other countries using social media, fake websites, funding for extremist parties, hacked private communications, and more. My colleague Edward Lucas, a senior fellow at the Center for European Policy Analysis, and I took it to Capitol Hill, to the State Department, and to anyone in Washington who would listen. The response was polite interest, nothing more. We are very sorry that Slovakia and Slovenia are having these problems, but it can’t happen here.

A few months later, it did happen here. Russian trolls operating from St. Petersburg sought to shift the outcome of an American election in much the same way they had done in Central Europe, using fake Facebook pages (sometimes impersonating anti-immigration groups, sometimes impersonating Black activists), fake Twitter accounts, and attempts to infiltrate groups like the National Rifle Association, as well as weaponizing hacked material from the Democratic National Committee. Some Americans actively welcomed this intervention, and even sought to take advantage of what they imagined might be broader Russian technical capabilities. “If it’s what you say I love it,” Donald Trump Jr. wrote to an intermediary for a Russian lawyer who he believed had access to damaging information about Hillary Clinton. In 2008, Trump Jr. had told a business conference that “Russians make up a pretty disproportionate cross section of a lot of our assets,” and in 2016, Russia’s long-term investment in the Trump business empire paid off. In the Trump family, the Kremlin had something better than spies: cynical, nihilistic, indebted, long-term allies.The list of major American corporations caught in tangled webs of personal, financial, and business links to autocratic regimes is very long.

Despite the raucous national debate on Russian election interference, we don’t seem to have learned much from it, if our thinking about Chinese influence operations is any indication. The United Front is the Chinese Communist Party’s influence project, subtler and more strategic than the Russian version, designed not to upend democratic politics but to shape the nature of conversations about China around the world. Among other endeavors, the United Front creates educational and exchange programs, tries to mold the atmosphere within Chinese exile communities, and courts anyone willing to be a de facto spokesperson for China. But in 2019, when Peter Mattis, a China expert and democracy promoter, tried to discuss the United Front program with a CIA analyst, he got the same kind of polite dismissal that Lucas and I had heard a few years earlier. “This is not Australia,” the CIA analyst told him, according to testimony Mattis gave to Congress, referring to a series of scandals involving Chinese and Chinese Australian businesspeople allegedly attempting to buy political influence in Canberra. We are very sorry that Australia is having these problems, but it can’t happen here.

Can’t it? Controversy has already engulfed many of the Chinese-funded Confucius Institutes set up at American universities, some of whose faculty, under the guise of offering benign Chinese-language and calligraphy courses, got involved in efforts to shape academic debate in China’s favor—a classic United Front enterprise. The long arm of the Chinese state has reached Chinese dissidents in the U.S. as well. The Washington, D.C., and Maryland offices of the Wei Jingsheng Foundation, a group named after one of China’s most famous democracy activists, have been broken into more than a dozen times in the past two decades. Ciping Huang, the foundation’s executive director, told me that old computers have disappeared, phone lines have been cut, and mail has been thrown in the toilet. The main objective seems to be to let the activists know that someone was there. Chinese democracy activists living in the U.S. have, like the Uyghurs in Istanbul, been visited by Chinese agents who try to persuade them, or blackmail them, to return home. Still others have had strange car accidents—mishaps regularly happen while people are on their way to attend an annual ceremony held in New York on the anniversary of the Tiananmen Square massacre.

Chinese influence, like authoritarian influence more broadly, can take even subtler forms, using carrots rather than sticks. If you go along with the official line, if you don’t criticize China’s human-rights record, opportunities will emerge for you. In 2018, McKinsey held a tone-deaf corporate retreat in Kashgar, just a few miles away from a Uyghur internment camp—the same kind of camp where the husbands, parents, and siblings of Tursun, Shirmemet, and Abdureshid have been imprisoned. McKinsey had good reasons not to talk about human rights at the retreat: According to The New York Times, the consulting giant at the time of that event advised 22 of the 100 largest Chinese-state companies, including one that had helped construct the artificial islands in the South China Sea that have so alarmed the U.S. military.

But perhaps it’s unfair to pick on McKinsey. The list of major American corporations caught in tangled webs of personal, financial, and business links to China, Russia, and other autocracies is very long. During the heavily manipulated and deliberately confusing Russian elections in September 2021, both Apple and Google removed apps that had been designed to help Russian voters decide which opposition candidates to select, after Russian authorities threatened to prosecute the companies’ local employees. The apps had been created by Alexei Navalny’s anti-corruption movement, the most viable opposition movement in the country, which was itself not allowed to participate in the election campaign. Navalny, who remains in prison on ludicrous charges, made a statement via Twitter excoriating American democracy’s most famous corporate moguls:

It’s one thing when the Internet monopolists are ruled by cute freedom-loving nerds with solid life principles. It is completely different when the people in charge of them are both cowardly and greedy … Standing in front of the huge screens, they tell us about “making the world a better place,” but on the inside they are liars and hypocrites.

The list of other industries that might be similarly described as “cowardly and greedy” is also very long, extending even to Hollywood, pop music, and sports. When distributors became nervous about a possible Chinese backlash to a 2012 MGM remake of a Cold War–era movie that recast the Soviet invaders as Chinese, the studio had the film digitally altered to make the bad guys North Korean instead. In 2019, NBA Commissioner Adam Silver, along with a number of basketball stars, expressed remorse to China after the general manager of the Houston Rockets tweeted support for the democrats of Hong Kong. Even more abject was Qazaq: History of the Golden Man, a fawning eight-hour documentary about the life of Nursultan Nazarbayev, the brutal longtime ruler of Kazakhstan, produced in 2021 by the Hollywood director Oliver Stone. Or consider what the rapper Nicki Minaj did in 2015, when she was criticized for giving a concert in Angola, hosted by a company co-owned by the daughter of that country’s dictator, José Eduardo dos Santos. Minaj posted two photos of herself on Instagram, one in which she’s draped in the Angolan flag and another alongside the dictator’s daughter, captioned with these immortal words: “Oh no big deal … she’s just the 8th richest woman in the world. (At least that’s what I was told by someone b4 we took this photo) Lol. Yikes!!!!! GIRL POWER!!!!! This motivates me soooooooooo much!!!!”

If the autocrats and the kleptocrats feel no shame, why should American celebrities who profit from their largesse? Why should their fans? Why should their sponsors?

If the 20th century was the story of a slow, uneven struggle, ending with the victory of liberal democracy over other ideologies—communism, fascism, virulent nationalism—the 21st century is, so far, a story of the reverse. Freedom House, which has published an annual “Freedom in the World” report for nearly 50 years, called its 2021 edition “Democracy Under Siege.” The Stanford scholar Larry Diamond calls this an era of “democratic regression.” Not everyone is equally gloomy—Srdja Popovic, the democracy activist, argues that confrontations between autocrats and their populations are growing harsher precisely because democratic movements are becoming more articulate and better organized. But just about everyone who thinks hard about this subject agrees that the old diplomatic toolbox once used to support democrats around the world is rusty and out of date.

The tactics that used to work no longer do. Certainly sanctions, especially when hastily applied in the aftermath of some outrage, do not have the impact they once did. They can sometimes seem, as Stephen Biegun, the former deputy secretary of state, puts it, “an exercise in self-gratification,” on par with “sternly worded condemnations of the latest farcical election.” That doesn’t mean they have no impact at all. But although personal sanctions on corrupt Russian officials might make it impossible for some Russians to visit their homes in Cap Ferrat, say, or their children at the London School of Economics, they haven’t persuaded Putin to stop invading other countries, interfering in European and American politics, or poisoning his own dissidents. Neither have decades of U.S. sanctions changed the behavior of the Iranian regime or the Venezuelan regime, despite their indisputable economic impact. Too often, sanctions are allowed to deteriorate over time; just as often, autocracies now help one another get around them.The centrality of democracy in American foreign policy has been declining for many years.

America does still spend money on projects that might loosely be called “democracy assistance,” but the amounts are very low compared with what the authoritarian world is prepared to put up. The National Endowment for Democracy, a unique institution that has an independent board (of which I am a member), received $300 million of congressional funding in 2020 to support civic organizations, non-state media, and educational projects in about 100 autocracies and weak democracies around the world. American foreign-language broadcasters, having survived the Trump administration’s still inexplicable attempt to destroy them, also continue to serve as independent sources of information in some closed societies. But while Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty spends just over $22 million on Russian-language broadcasting (to take one example) every year, and Voice of America just over $8 million more, the Russian government spends billions on the Russian-language state media that are seen and heard all over Eastern Europe, from Germany to Moldova to Kazakhstan. The $33 million that Radio Free Asia spends to broadcast in Burmese, Cantonese, Khmer, Korean, Lao, Mandarin, Tibetan, Uyghur, and Vietnamese pales beside the billions that China spends on media and communications both inside its borders and around the world.

Our efforts are even smaller than they look, because traditional media are only a part of how modern autocracies promote themselves. We don’t yet have a real answer to China’s Belt and Road Initiative, which offers infrastructure deals to countries around the globe, often enabling local leaders to skim kickbacks and garnering positive China-subsidized media coverage in return. We don’t have the equivalent of a United Front, or any other strategy for shaping debate within and about China. We don’t run online influence campaigns inside Russia. We don’t have an answer to the disinformation, injected by troll farms abroad, that circulates on Facebook inside the U.S., let alone a plan for countering the disinformation that circulates inside autocracies.

President Biden is well aware of this imbalance and says he wants to reinvigorate the democratic alliance and America’s leading role within it. To that end, the president is convening an online summit on December 9 and 10 to “galvanize commitments and initiatives” in aid of three themes: “defending against authoritarianism, fighting corruption, and promoting respect for human rights.”

That sounds nice, but unless it heralds deep changes in our own behavior it means very little. “Fighting corruption” is not just a foreign-policy issue, after all. If we in the democratic world are serious about it, then we can no longer allow Kazakhs and Venezuelans to purchase property anonymously in London or Miami, or the rulers of Angola and Myanmar to hide money in Delaware or Nevada. We need, in other words, to make changes to our own system, and that may require overcoming fierce domestic resistance from the business groups that benefit from it. We need to shut down tax havens, enforce money-laundering laws, stop selling security and surveillance technology to autocracies, and divest from the most vicious regimes altogether. “We” here will need to include Europe, especially the U.K., as well as partners elsewhere—and that will require a lot of vigorous diplomacy.

The same is true of the fight for human rights. Statements made at a diplomatic summit won’t achieve much if politicians, citizens, and businesses don’t act as if they matter. To effect real change, the Biden administration will have to ask hard questions and make big decisions. How can we force Apple and Google to respect the rights of Russian democrats? How can we ensure that Western manufacturers have excluded from their supply chains anything produced in a Uyghur concentration camp? We need a major investment in independent media around the world, a strategy for reaching people inside autocracies, new international institutions to replace the defunct human-rights bodies at the UN. We need a way to coordinate democratic nations’ response when autocracies commit crimes outside their borders—whether that’s the Russian state murdering people in Berlin or Salisbury, England; the Belarusian dictator hijacking a commercial flight; or Chinese operatives harassing exiles in Washington, D.C. As of now, we have no transnational strategy designed to confront this transnational problem.

This absence of strategy reflects more than negligence. The centrality of democracy to American foreign policy has been declining for many years—at about the same pace, perhaps not coincidentally, as the decline of respect for democracy in America itself. The Trump presidency was a four-year display of contempt not just for the American political process, but for America’s historic democratic allies, whom he singled out for abuse. The president described the British and German leaders as “losers” and the Canadian prime minister as “dishonest” and “weak,” while he cozied up to autocrats—the Turkish president, the Russian president, the Saudi ruling family, and the North Korean dictator, among them—with whom he felt more comfortable, and no wonder: He has shared their ethos of no-questions-asked investments for many years. In 2008, the Russian oligarch Dmitry Rybolovlev paid Trump $95 million—more than twice what Trump had paid just four years earlier—for a house in Palm Beach no one else seemed to want; in 2012, Trump put his name on a building in Baku, Azerbaijan, owned by a company with apparent links to Iran’s Revolutionary Guard Corps. Trump feels perfectly at home in Autocracy Inc., and he accelerated the erosion of the rules and norms that has allowed it to take root in America.

At the same time, a part of the American left has abandoned the idea that “democracy” belongs at the heart of U.S. foreign policy—not out of greed and cynicism but out of a loss of faith in democracy at home. Convinced that the history of America is the history of genocide, slavery, exploitation, and not much else, they don’t see the value of making common cause with Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, Nursiman Abdureshid, or any of the other ordinary people around the world forced into politics by their experience of profound injustice. Focused on America’s own bitter problems, they no longer believe America has anything to offer the rest of the world: Although the Hong Kong prodemocracy protesters waving American flags believe many of the same things we believe, their requests for American support in 2019 did not elicit a significant wave of youthful activism in the United States, not even something comparable to the anti-apartheid movement of the 1980s.

Incorrectly identifying the promotion of democracy around the world with “forever wars,” they fail to understand the brutality of the zero-sum competition now unfolding in front of us. Nature abhors a vacuum, and so does geopolitics. If America removes the promotion of democracy from its foreign policy, if America ceases to interest itself in the fate of other democracies and democratic movements, then autocracies will quickly take our place as sources of influence, funding, and ideas. If Americans, together with our allies, fail to fight the habits and practices of autocracy abroad, we will encounter them at home; indeed, they are already here. If Americans don’t help to hold murderous regimes to account, those regimes will retain their sense of impunity. They will continue to steal, blackmail, torture, and intimidate, inside their countries—and inside ours.

No comments:

Post a Comment