Three years later Sharma travelled to China to meet his hero, taking a selfie with him and securing the first of several investments from Alibaba. The Chinese ecommerce and fintech group went on to pump hundreds of millions of dollars into Sharma’s fast-growing start-up Paytm, building up a 30 per cent stake in the Indian payments company.

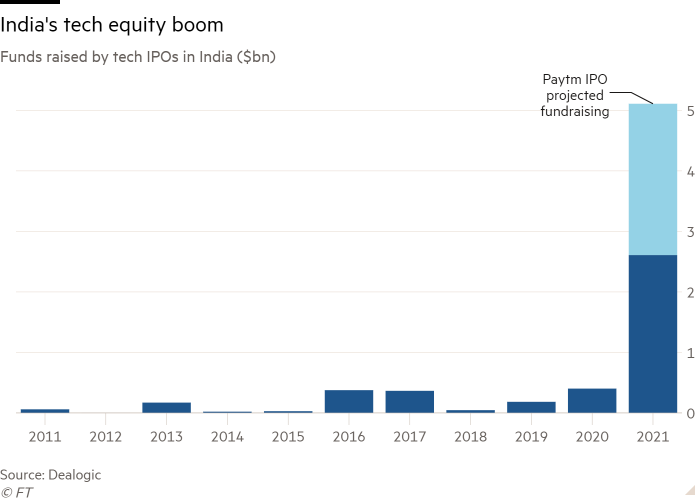

Paytm is now set for a $2.5bn listing on Thursday, India’s largest ever IPO. It is the biggest test to date of whether India’s start-ups can recreate the success of a generation of Chinese tech groups that remade the country’s stock market, and provide the exit routes investors need to have confidence in the market.

The group’s stock debut comes one year after Chinese regulators scuppered the $37bn IPO of Ant Group, Alibaba’s fintech arm and Paytm’s largest investor. It marked the beginning of a relentless crackdown on tech companies involved in everything from education to delivery services, wiping billions from the stock market and scaring away investors.

India, long a promising but second choice Asian market for investors, has emerged as a leading beneficiary of the divergence in fortunes between the tech sectors in the two countries. This, along with ample global liquidity and rapid internet adoption, has fuelled a private- and public-market bull run in India.

China “had sucked the air out of the room in terms of investor attention and focus”, says Timothy Moe, chief Asia-Pacific equity strategist at Goldman Sachs. “But because China is off the boil, it has accelerated investor attention at alternatives such as India.”

The share offering for Paytm, founded by Vijay Shekhar Sharma, has not attracted as much demand as other recent Indian IPOs © Udit Kulshrestha/FT

The share offering for Paytm, founded by Vijay Shekhar Sharma, has not attracted as much demand as other recent Indian IPOs © Udit Kulshrestha/FT“The bar to invest in China, public or private, is higher,” a partner at a foreign venture capital firm adds. “India will be a beneficiary.”

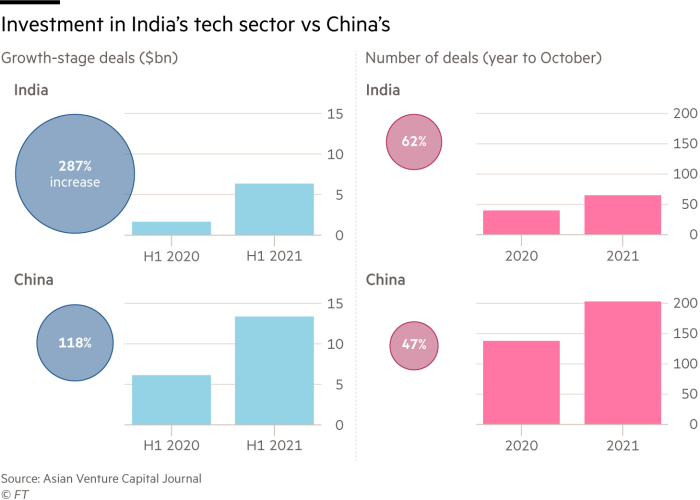

For every dollar invested in Chinese tech in the quarter that ended September, $1.50 went into India, according to the Asian Venture Capital Journal. India’s benchmark Sensex equity index is up 25 per cent this year, the best performer among Asia’s large economies, while China’s Shanghai SE Composite index is flat over the same period.

The Financial Times spoke to multiple investors who had diverted funds from China to India and elsewhere but declined to speak on the record due to still having holdings and clients in China.

“It’s about thinking where you look, how you play the different markets,” says Kabir Narang, a partner at B Capital Group, an investment firm active across Asia. “I think everyone in the world over the last six to 12 months has adjusted to” the regulatory action in China, he adds.

It is unclear how long the additional investor enthusiasm for Indian tech will last. There are fears the country’s buoyant tech markets are already overheated as competition to buy stakes inflates valuations and leaves companies and retail investors vulnerable to corrections.

Sceptics see the Ant- and SoftBank-backed Paytm — whose lossmaking businesses have struggled against Google, and Walmart’s Flipkart — as a test of how far investors will buy into the hype. Its share offering did not attract as much demand as other recent IPOs like Zomato, something analysts ascribed to its $20bn valuation and tough competition.

“These new age [tech] IPOs are not growth money. They are exit money,” allowing investors to sell, says Anurag Singh, managing partner at hedge fund Ansid Capital, which has not invested in the recent IPOs. “The same usual suspects — SoftBank, Alibaba . . . are looking for a smart exit, and they time it to perfection.”

‘This is India’s moment’

The scrapping of Ant’s IPO by Chinese authorities last year swelled into a blizzard of regulatory changes and probes aimed at everything from curbing monopolistic behaviour to data privacy and wealth distribution. The powerful Ma, as well as national champions like Tencent and Meituan, the shopping platform, were all ensnared.

While the clampdown has slowed, the threat of curbs still hangs over many Chinese companies. Ant Group, for example, has not revived its scuttled IPO. The fate of Didi Chuxing, China’s leading ride-hailing app and another high-profile casualty, is also uncertain.

Two days after Didi’s blockbuster IPO on the New York Stock Exchange in June, Chinese regulators announced a probe into the company over data security, wiping out one-fifth of its market value. The investigation is continuing and Didi’s share price is languishing more than 40 per cent below the offer price.

Investors are now redeploying their capital given the “non-linear” developments in China, says Nick Xiao, the chief executive of Chinese wealth manager Hywin’s Hong Kong arm.

Funds raised by technology start-ups via public listings in mainland China are on track for the first annual drop in seven years while tech listings in India have so far raised $2.6bn in 2021, a jump of 550 per cent compared to last year’s total. China still leads in terms of the number of private market deals — a gap reflecting its head start fostering a homegrown tech sector — but India’s growth rates have outpaced it this year. Mid-stage deals in India for the quarter to the end of September were up 93 per cent from last year, compared to a 3 per cent drop in China, according to the AVCJ.

While south-east Asia has also benefited from the shift, India’s size has made it a natural alternative. “India is getting the attention of almost everybody,” Xiao says. “When talking to our global family office clients, I can see this trend.”

Alibaba’s Jack Ma, once China’s richest man, saw his fortune drop after regulators slammed the brakes on his Ant Group’s IPO © Helen Roxburgh/AFP/Getty Images

Alibaba’s Jack Ma, once China’s richest man, saw his fortune drop after regulators slammed the brakes on his Ant Group’s IPO © Helen Roxburgh/AFP/Getty ImagesHywin recently launched a global healthcare fund with a mandate to look at countries including India. Many of his clients are gaining exposure to the country including via equities, Xiao adds.

Didi’s predicament contrasted with the July listing in India of Zomato, a food delivery group and the first of the country’s lossmaking tech companies to go public. Despite scepticism over its cash burn and uncertain path to profitability, Zomato’s shares have doubled from its issue price to a $15bn valuation.

This has demonstrated “the wherewithal and capacity of the Indian capital markets to offer a platform for essentially lossmaking technology companies”, says Karam Daulet-Singh, managing partner of Touchstone Partners, which advises foreign investors. “This time last year the holy grail was an offshore listing, a Spac, and maybe even a strategic [investor] buying the company outright.”

Daulet-Singh adds that domestic trends would attract investors regardless of events elsewhere. “The regulatory crackdown that China has undertaken over the last 12 months has pushed investors to look at India more favourably,” he says. “But it’s not just push, there’s pull as well. The pull is the rapid digitalisation that’s taking place [in India].”

While listed “new economy” companies account for 60 per cent of China’s MSCI index, they make up only 5 per cent of India’s, according to Goldman Sachs.

Other companies have followed Zomato. Shares in Nykaa, a cosmetics and beauty products ecommerce group, almost doubled from its issue price after its November debut. Oyo, the SoftBank-backed hotel group forced to downsize its cash-burning business, wants to raise $1.1bn through a listing. Ola, a ride-sharing company trying to branch out into electric vehicle manufacturing, plans to file a prospectus in the coming months and raise as much as $2bn, according to people familiar with the matter.

“In a way, this is India’s moment of coming on to the global stage,” Bhavish Aggarwal, Ola’s chief executive, says. “You’ll see a lot of value creation coming from India.”

But investors warn the market is vulnerable if the listings pipeline of richly valued, lossmaking companies struggle to match high investor expectations, especially if those companies fail to show they can turn a profit. Zomato’s losses in the quarter to the end of September nearly doubled to Rs4.4bn, though its shares continued to rise.

“Paytm, Zomato, Oyo — these companies lose a lot given how mature they are and the fact that their revenues are not huge,” says Jeffrey Lee Funk, a technology consultant. The problem is not confined to India, he adds. “All countries have the problem of overvalued start-ups” thanks to the abundance of global private capital.

Chief executive Bhavish Aggarwal, pictured with a new Ola electric scooter, says investors will see a lot of value creation in India © AFP via Getty Images

Chief executive Bhavish Aggarwal, pictured with a new Ola electric scooter, says investors will see a lot of value creation in India © AFP via Getty ImagesPaytm, in particular, will be closely watched. It is positioning itself as India’s answer to Chinese “super apps” like Ant covering everything from digital payments to insurance. And while it has expanded furiously into sectors as diverse as flight tickets and mobile gaming, big bets on ecommerce and digital wallets floundered. It has lost mobile payments market share to Google and Flipkart’s PhonePe, which soared on the back of India’s Unified Payments Interface technology. It touts a user base of 330m accounts but only 15 per cent of those make any transactions in a given month.

While bullish brokers argue Paytm is well placed to ride the growth of Indian fintech, others say the company offers little to justify a rich valuation of 43 times price to sales, which have fallen since 2019.

Sharma, Ant and SoftBank are all selling chunks of their stakes. And while demand for its share offering outstripped supply by 1.9 times, it was far behind 38 times for Zomato or more than 80 times for Nykaa.

Ant’s headquarters in Hangzhou, China. The group’s IPO hopes were dashed when regulators intervened last year © Qilai Shen/Bloomberg

Ant’s headquarters in Hangzhou, China. The group’s IPO hopes were dashed when regulators intervened last year © Qilai Shen/Bloomberg“The digital economy is about winner-takes-all. People remember the top guy and the second. The third disappears into oblivion. Paytm is a distant third,” Ansid’s Singh says. “It’s easy to say I’m trying to be a super app. The track record says it hasn’t worked anywhere.”

Bubble territory?

India is set to surpass China as the world’s most populous country in coming years. It has 375m Gen Zers, born between 1996 and 2010, compared to around 250m in China, according to EY. Internet penetration of less than 60 per cent remains well below China, according to Goldman Sachs, leaving room for growth.

This demographic potential has long helped investors stomach rich valuations. And Indian entrepreneurs say they have never seen so much competition for deals. Vikram Chopra, chief executive of online used-vehicle seller Cars24, says a round raising $450m from SoftBank and Tencent in September was subscribed three times over.

Analytics platform Venture Intelligence says 35 Indian start-ups have become “unicorns” worth over $1bn this year, more than every year since 2013 combined. The youngest new entrant was Apna, a job-finding platform founded less than two years ago, which was valued at more than $1bn after a September fundraising round involving New York hedge fund Tiger Global and Silicon Valley’s Sequoia Capital.

Yet, this inflation in valuations is deterring some investors worried about overheating. “It is a lot more expensive in India than it used to be. I [invested in] about 50 or 60 start-ups in India but now I am more likely to go to Pakistan or Bangladesh,” says William Bao Bean, a Shanghai-based general partner at global venture capital fund SOSV.

“I’m hugely worried,” another investor at a foreign venture capital fund says, warning that the Indian market was becoming a “bubble”. “It’s very scary. A billion dollar valuation is meaningless today. It doesn’t mean the company has anything figured out.”

Many investors are yet to see any returns. Cars24 recorded a return on invested capital of minus 53 per cent in the year ended March 2020, the latest financial details available from Singapore’s Accounting and Corporate Regulatory Authority show.

Udaan, an ecommerce company whose investors include Silicon Valley’s Lightspeed, reported a return on invested capital of minus 80 per cent from the same period.

Potential IPO-bound companies in India had an average price-to-sales ratio of 21 over the past three years, according to Goldman, compared to three for the wider Nifty index.

India’s Oyo hotels hopes to raise $1.1bn through a listing © Toru Hanai/Bloomberg

India’s Oyo hotels hopes to raise $1.1bn through a listing © Toru Hanai/BloombergIndia “is more richly valued than China was at the same stage,” Moe says. “In India there was more private market gestation before things became public. That might mean the starting point for public sector investors is not quite as advantageous.”

For all its potential, spending power in India remains far behind China and gross domestic product per capita of below $2,000 is less than a fifth of that in its neighbour.

Some analysts also caution that the narrative around scale may be overblown. Despite India’s 1.4bn population, size estimates for the sorts of digitally savvy, affluent consumers splashing out on tech services number in the tens of millions.

While China’s unpredictable tech crackdown highlighted India’s comparative stability, investors face risks of their own. India’s investment reputation has historically been damaged by controversial policies like a now-scrapped retrospective tax amendment used to pursue billions from foreign investors.

Foreign money is pouring into sectors operating in regulatory grey areas, from online lending to cryptocurrencies — which have been threatened with bans. Fantasy sports apps, wildly popular with investors and users alike, offer the ability to wager real money on cricket matches despite repeated legal challenges over their alleged similarity to outlawed sports betting.

Indian food delivery group Zomato’s shares have doubled from its issue price to a $15bn valuation despite scepticism over its cash burn © Debarchan Chatterjee/NurPhoto/Getty Images

Indian food delivery group Zomato’s shares have doubled from its issue price to a $15bn valuation despite scepticism over its cash burn © Debarchan Chatterjee/NurPhoto/Getty ImagesIn October Dream11, a Tiger Global portfolio company, suspended operations in the state of Karnataka, one of its biggest markets, after a police complaint following a state gambling ban.

Investors and analysts say that regulatory pressure could increase as sectors start handling bigger sums of user money.

“There are some sectors where the government does not have a clear stance, crypto being one example,” says Neha Singh, the co-founder of Tracxn, a data platform. But, she adds, bullish investors appear nonchalant. While “investors were not sure earlier about whether to invest in a sector, that currently does not seem to be a concern”.

Larry Illg, a senior executive at Prosus, the investment arm of South Africa’s Naspers, the internet group, says Indian companies could face regulatory setbacks but he remains optimistic. “Is it going to be a straight line? No. It’s going to be bumpy. We take that kind of horizon on our investments.

“If you’re looking for predictability, [venture capital] is the wrong industry,” he adds. “The reality is some of these industries are just taking shape.”

No comments:

Post a Comment