Nathaniel Allen and Matthew La Lime

Earlier this year, an international reporting project based on a list of 50,000 phone numbers suspected of being compromised by the Pegasus spyware program revealed just how widespread digital espionage has become. Pegasus, which is built and managed by the Israeli firm NSO Group, turns mobile phones into surveillance tools by granting an attacker full access to a device’s data. It is among the most advanced pieces of cyber espionage software ever invented, and its targets include journalists, activists, and politicians. Of the 14 numbers belonging to world leaders on the list of numbers suspected of being targeted, half were African. They included two sitting heads of state—South Africa’s Cyril Ramaphosa and Morocco’s King Mohammed VI —along with the current or former prime ministers of Egypt, Burundi, Uganda, Morocco, and Algeria.

That African leaders are both victims and users of malware systems such as Pegasus should come as little surprise. Governments on the continent have for some time relied on Pegasus and other spyware to track terrorists and criminals, snoop on political opponents, and spy on citizens. However, recent reporting about NSO Group’s surveillance tools—dubbed the “Pegasus Project”— makes clear that governments across Africa are also using spyware for purposes of international espionage. And these tools are being used in ways that risk worsening authoritarian tendencies and raise questions about whether security services are being properly held to account for their use.

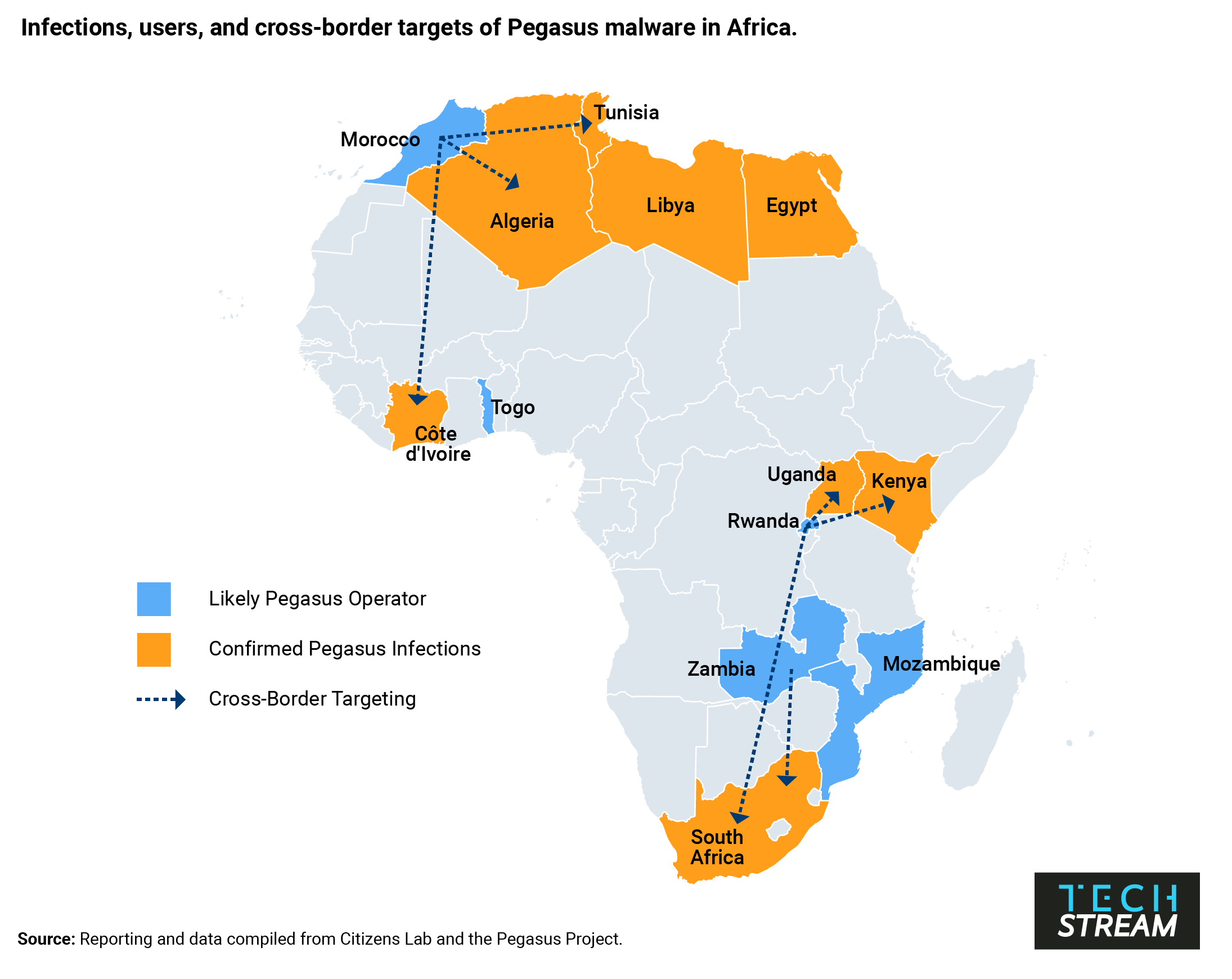

“Likely Pegasus Operator” refers to the five African countries identified either by Citizens Lab or Pegasus Project reporting as a country that licenses or operates Pegasus malware. Pegasus infections have been found in all countries that are suspected operators except for Mozambique. By contrast, there were confirmed infections in eight African countries who are not suspected to be operators. Users in these countries were presumably targeted, either deliberately or incidentally, by other countries operating Pegasus. The “Cross-Border Targeting” arrows indicate operators that either Pegasus Project reporting or Citizens Lab suggested were involved in cross-border targeting within Africa, and which countries were the targets.

“Likely Pegasus Operator” refers to the five African countries identified either by Citizens Lab or Pegasus Project reporting as a country that licenses or operates Pegasus malware. Pegasus infections have been found in all countries that are suspected operators except for Mozambique. By contrast, there were confirmed infections in eight African countries who are not suspected to be operators. Users in these countries were presumably targeted, either deliberately or incidentally, by other countries operating Pegasus. The “Cross-Border Targeting” arrows indicate operators that either Pegasus Project reporting or Citizens Lab suggested were involved in cross-border targeting within Africa, and which countries were the targets.Digitizing espionage in Africa

Previously, cyber espionage concerns in Africa have centered around China’s widely publicized hacking of the African Union. While the threat from China and other major cyber powers remains significant, the Pegasus Project’s revelations provide the first publicly documented indication that African countries are using digital espionage capabilities to spy on other governments, including fellow African ones. Ramaphosa appears to have been selected as a potential target by Rwanda in 2019. Morocco listed the numbers of dozens of Algerian and French officials, including the French President Emmanuel Macron, as possible targets.

This may be only the tip of the iceberg. Pegasus is far from the only cyber espionage software ostensibly meant to aid law enforcement fight criminals that is being used for more nefarious purposes. Digital surveillance is a booming industry in Africa. Major players include not just NSO Group, but China-based Huawei, UK-based Gamma Group, Milan-based Hacking Team, and the French firm Amesys. All these firms have sold cyber espionage tools to African clients who have used the software to track or crack down on dissidents. Many African leaders seem aware that their devices are not secure. Some, like Rwanda’s Paul Kagame and Côte d’Ivoire’s Alassane Ouattara, have taken stringent measures to secure their phones. Others, such as Cameroon’s Paul Biya, reportedly eschew mobile communications altogether.

According to Pegasus Project revelations, politicians and government officials from 34 countries were targeted by NSO spyware. Of these countries, 30 were in the Global South. On the one hand, this may reflect just how vulnerable countries in Africa and the Global South are to digital espionage due to limited investments in cybersecurity and legal protections. On the other, it could simply reflect a preference by the security sector and spy agencies in the Global South to invest in relatively cheap spyware built by external actors rather than develop it in-house, as is more common in industrialized countries with significant offensive cyber capabilities.

Digital espionage tools abetting authoritarian tendencies

For autocratic regimes such as Rwanda, the appeal of digital espionage tools is apparent. Pegasus offers an easy-to-use platform to simultaneously track domestic political dissidents, international activists, and foreign governments. According to Amnesty International, Rwanda has used NSO software to target as many as 3,500 “activists, journalists, political opponents, foreign politicians, and diplomats.”

Pegasus appears to have been particularly useful in allowing the Rwandan government to attempt to silence political dissent outside of the country’s borders. In addition to Ramaphosa, Rwanda used Pegasus to surveil former intelligence chief and opposition party co-founder Kayumba Nyamwasa, who is living in exile in South Africa and has survived repeated attempts on his life. The mobile device of Carine Kanimba, a U.S.-Belgian dual citizen and daughter of the activist who inspired the film Hotel Rwanda, was likewise compromised. Kanimba is fighting to free her father from prison after he was forcibly abducted by Rwandan authorities last year in Dubai.

Yet authoritarian regimes are not the only ones suspected of employing Pegasus malware. Data compiled by the research group Citizen Lab indicates that Zambia and Mozambique, two democratic leaning states, may be operating Pegasus software. It is possible that these governments are using the malware for legitimate law enforcement purposes. Little is known about the use of Pegasus by either regime, and in the case of Mozambique, Citizens Lab did not identify any Pegasus-related infections within the country. However, given recent revelations that Zambian cybersecurity officials intercepted encrypted communications and tracked the movements of political opponents with externally-supplied technology, it is likely that Pegasus has been used to undermine democracy at some level in Zambia. It is worth noting that Zambia’s embrace of Pegasus appears to have coincided with the reign of recently ousted president Edgar Lungu, who presided over a period of democratic decline.

Digital espionage and security sector accountability

Most reporting and analysis focused on how governments are using digital espionage tools to undermine democracy through the surveillance and censorship of political opposition figures, human rights activists, and protestors. But the proliferation of easy-to-use and powerful spyware also potentially gives security sector officials added ability to monitor civilian government officials.

Morocco is one of NSO Group’s largest clients and has used Pegasus to target as many as 10,000 numbers. It is, along with Rwanda, the only with African country confirmed to have used Pegasus malware to spy on foreign government officials. But that isn’t all. Morocco’s intelligence services also “appear to have selected their own King Mohammed VI as a person of interest.” This appears to be the only confirmed case in which a country’s security services used Pegasus malware to monitor their own sitting head of state. In Mexico, which is the only Pegasus customer to have targeted more numbers than Morocco, ex-President Felipe Calderon appears to have been added as a person of interest after he left office.

If security intelligence services in Morocco and elsewhere can use digital spyware to monitor heads of state without their knowledge and consent, the consequences are likely to be deeply destabilizing. This year, Africa has experienced six coup attempts and four successful coups, the most since the 1990s. In countries where security services face limited oversight and accountability, the acquisition of digital monitoring and surveillance technology may make it easier to undermine civilian control of the security sector and to coordinate illegal attempts to seize power.

A lack of good solutions to curb spyware

If there is any good news for those who wish to reduce the spread of digital espionage tools, it is that the regimes directly implicated in cross-border spying have faced serious backlash for doing so. Prior to the revelations that Rwanda attempted to compromise the phone of Ramaphosa, the governments of Rwanda and South Africa were taking steps to improve their relations. The Pegasus revelations, along with tensions over a regional military intervention in Mozambique, have put these efforts at risk. For Morocco, the fallout has been even more severe. The French government is conducting a probe that could result in criminal charges against Moroccan officials for using Pegasus to spy on French journalists. Algerian authorities were also livid. A month after the Pegasus Project revelations, Algeria formally broke diplomatic ties with Morocco, citing “massive and systemic acts of espionage” as one of a number of reasons for the decision.

Despite the backlash, there are few solutions to curbing digital espionage of this sort. Experts like Steven Feldstein argue that what is truly needed to stem the tide is “a binding and enforceable export controls regime to stop the spread of dangerous surveillance tools to bad actors.” But for the moment, such a regulatory framework appears unlikely to gain traction internationally. A more feasible and immediate course of action would be for technologically advanced countries across the world to independently ban firms from selling spyware and surveillance products to countries who misuse them. The U.S. Commerce Department recently added NSO Group to the so-called “entity list,” cutting the firm off from U.S. suppliers. This may make it more difficult for NSO to operate but falls short of addressing the broader proliferation of digital spyware.

Setting limits on the sale and export of such technology is unlikely to eliminate the proliferation of spyware across the Global South. This is especially true in Africa, where states place few restrictions on whom they do business with. Global bans and international regulatory frameworks are unlikely to curb the spread of spyware so long as there exists just one non-compliant country or company with the ability and the intent to sell cyber espionage tools to the highest bidder. As a result, the onus to forgo the use of spyware technology in domestic and international affairs will fall on African states themselves. To ensure this technology is used accountably and for the right purposes, Africans must continue to work to build strong, democratic institutions and promote effective executive and security sector oversight.

No comments:

Post a Comment