LEITH GREENSLADE

NEW YORK – COVID-19 has exposed the limited ability of health systems around the world to cope with a pandemic of respiratory infection. With the official death count from COVID-19 now over five million, and the unofficial count estimated at up to five times higher, the struggles of health systems everywhere have been evident to all.

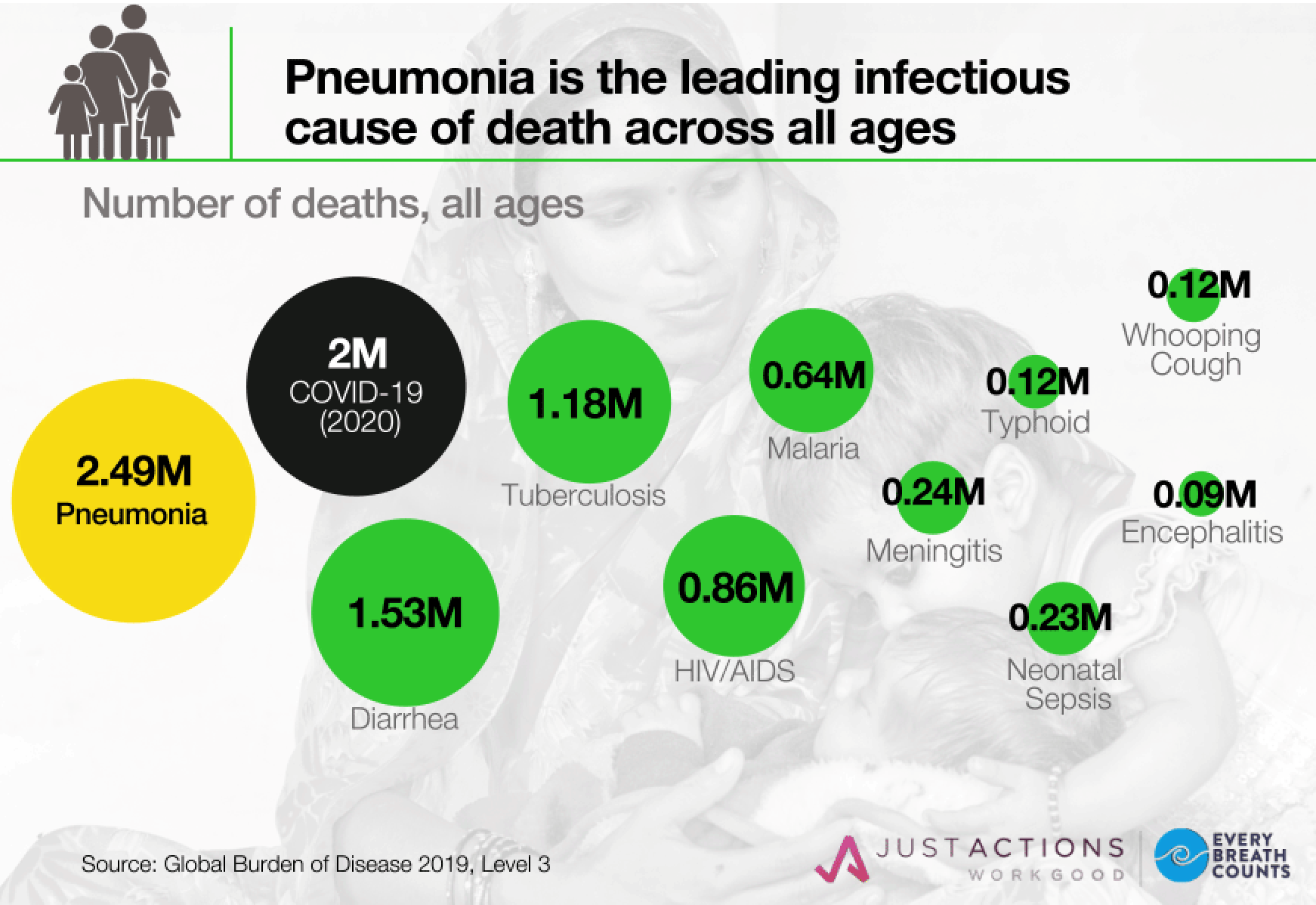

What is less clear is how the world could have been so blindsided by COVID-19. Respiratory diseases have long been the leading infectious cause of death globally. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, an estimated 2.5 million adults and children died from pneumonia each year. No other infection causes anywhere near this number of fatalities.

And pneumonia deaths occur in all countries. In high-income countries, deaths are concentrated among older adults, while in low-income countries, children are the primary victims. Many middle-income countries struggle with large numbers of deaths among both groups.

Given these data, respiratory infections have been the most consequential “missing piece” of the global health agenda. Prior to the pandemic, there had never been a global health campaign focused on reducing pneumonia deaths or a global health agency responsible for supporting countries to prevent, diagnose, and treat pneumonia.

Even Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, which has a mandate to vaccinate the world’s most vulnerable children, has not been able to protect more than half of them with one of the most powerful weapons against pneumonia – the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV). This leaves a lot of children – more than 350 million under the age of five – dangerously exposed.

Not even the wake-up calls provided by two respiratory infection outbreaks – severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS-CoV) in 2002 and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS-CoV) in 2014 – were enough to persuade national governments and global health agencies to emphasize pneumonia control.

As a result, health systems on every continent were unprepared when SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, emerged and quickly became a pandemic. National health authorities were ill-equipped to deal with waves of people needing rapid diagnosis and treatment – especially the massive amounts of medical oxygen required by COVID-19 patients.

Tragic stories of deaths due to lack of access to care began emerging from Latin America in the early summer of 2020 and soon spread to Asia, the Middle East, and Africa. It is impossible to forget the suffering of patients struggling to breathe or the plight of family members and health professionals desperately searching for oxygen.

We do not know how many COVID-19 deaths resulted from the unavailability of diagnosis and treatment, but many of the countries with the highest COVID-19 death rates have reported low testing rates and oxygen shortages. Now, more than 18 months into the pandemic and despite the availability of effective vaccines, governments are still scrambling to reduce the death toll. Of the 50,000 COVID-19 deaths that continue to occur each week, 70% are in low- and middle-income countries.

This is unacceptable. The COVID-19 pandemic must become a turning point for pneumonia control everywhere. Countries should never again suffer mass fatalities as a result of a respiratory infection pandemic. And such large numbers of people should not continue to die from non-COVID-related pneumonia year after year.

But they will, unless national governments turn their reactive pandemic-response plans into proactive pneumonia-control strategies. Putting into place a permanent, effective way to respond to pneumonia would reduce respiratory deaths from all kinds of infections and decrease the risk of another respiratory pandemic.

Achieving this goal will require full coverage of powerful pneumonia-fighting vaccines, better diagnostic tools at all levels of health-care systems, and improved access to treatments. It will also require action to reduce the leading risk factors for pneumonia death, including air pollution, child wasting, and smoking.

Global health and development agencies like the Global Fund, the World Bank, Unitaid, the World Health Organization, and the United Nations Children’s Fund should turn the COVID-19 support they have been providing to low- and middle-income countries into long-term pneumonia control programs. The Access to COVID-19 Tools Accelerator (ACT-A) Oxygen Emergency Taskforce alone has provided more than $600 million in oxygen supplies to countries in need and should be funded by the G20 to do more. And private philanthropies should continue supporting efforts by NGOs to strengthen respiratory care services beyond the pandemic.

Without this continued support, the world will remain exposed to the possibility of another respiratory infection pandemic. And we will risk failing to achieve many of the Sustainable Development Goals for health, especially the targets for reducing maternal, newborn, and child deaths and lowering communicable and non-communicable disease burdens.

Although COVID-19 has exposed some critical flaws in the global health architecture, it has also revealed how much national governments, global health and development agencies, and donors can accomplish when pressed to invest in the fight against respiratory infections. And there is much left to do.

After all, our world is changing in ways that will accelerate the risk of another respiratory pandemic. Airborne infections spread by breathing, talking, laughing, and singing will thrive in a warmer, highly urbanized, and mobile environment where poor diets, chronic conditions, and longer life spans increase vulnerability to illness and death. The cost of not investing the resources needed to fight pneumonia will be measured in millions of lives lost every year and millions more every time a new pandemic strikes.

No comments:

Post a Comment