Francesco Casarotto

France and Italy plan to sign the Quirinal Treaty, an agreement meant to improve bilateral relations generally and economic coordination and industrial ties specifically, by the end of the year. Originally proposed in 2017, the deal was shelved in 2018, when a more euroskeptic government came to power in Rome. Border issues and migration only made things worse between them. But the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent economic downturn have forced France and Italy to set aside their differences and place the Quirinal Treaty back at the top of their diplomatic agendas.

The timing is no coincidence. By March 2022, the European Central Bank’s emergency bond-buying scheme will end, and by the end of 2022, the eurozone budgetary and fiscal rules that had been suspended to help states cope with the pandemic are expected to be reinstated. France and Italy oppose the return of a pre-pandemic status quo, which pits them against Germany and other northern countries such as the Netherlands and Austria that advocate for tighter eurozone rules. In other words, Paris and Rome are getting closer in the hopes of forming a counterweight to the requests of the so-called frugal EU states. For France and Italy, nothing less than domestic stability is at stake.

Economic Stability, Domestic Stability

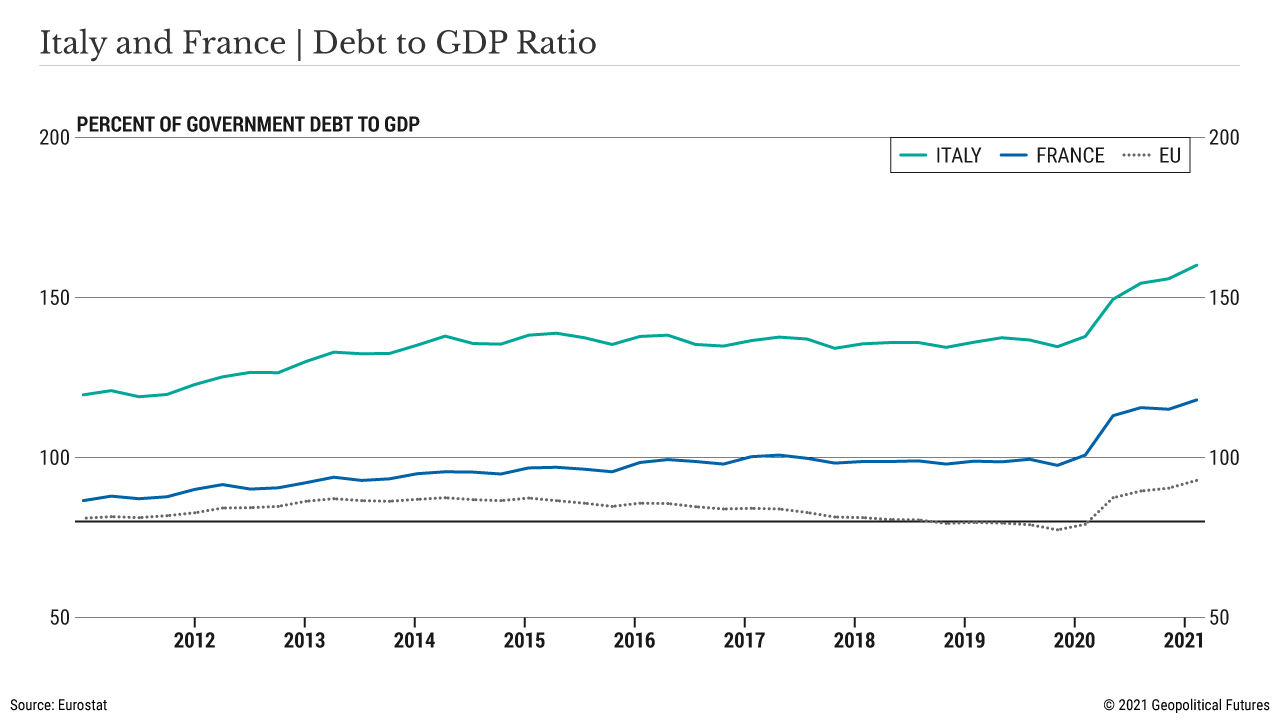

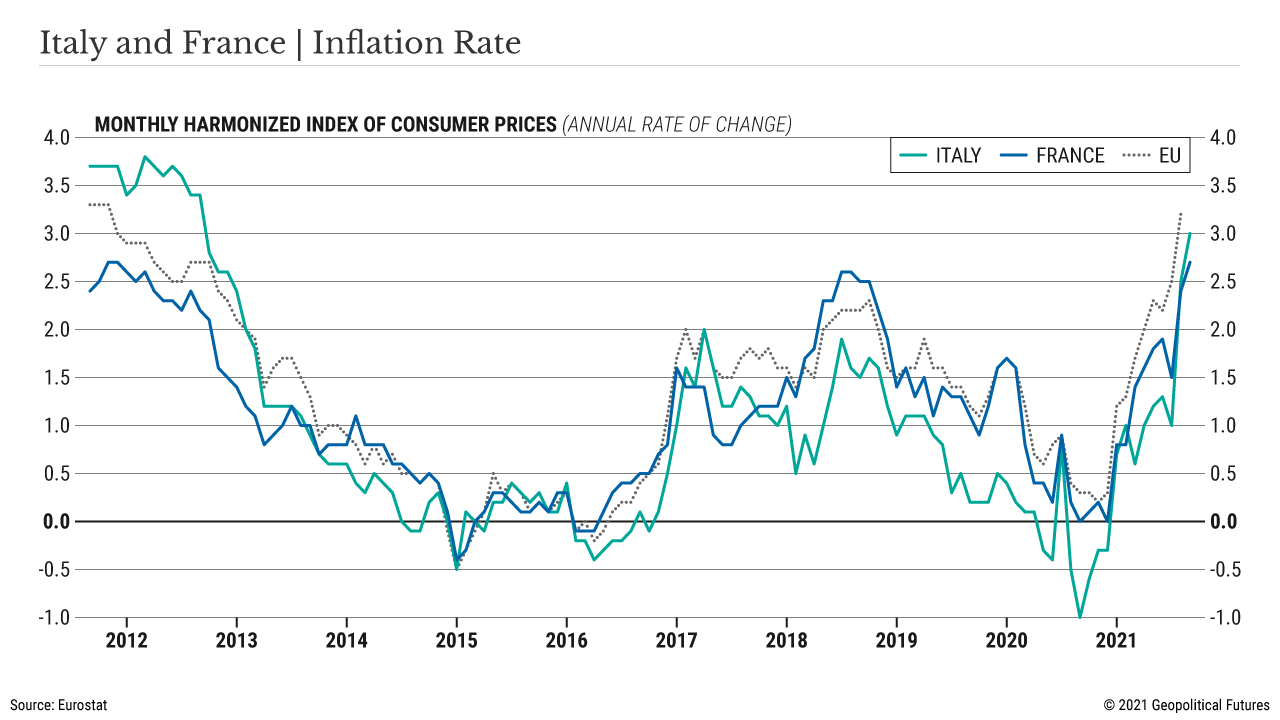

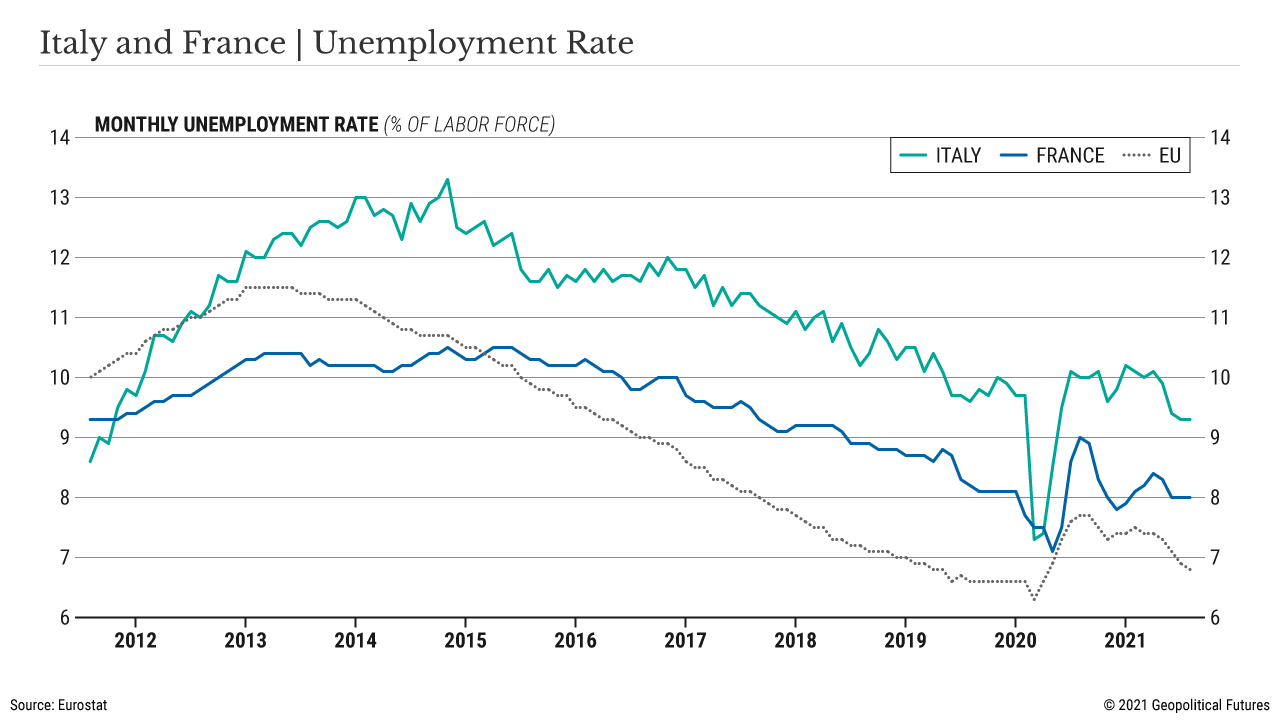

Though the size and precarity of their economies differ dramatically, Paris and Rome found themselves in similar economic situations after the eurozone crisis in 2011. Both saw an increase in their debt-to-gross domestic product ratio (roughly 98 percent for France and roughly 135 percent for Italy). Both suffered from excessively low inflation rates, which can hurt consumption and investment. And both experienced similar unemployment rates. France and Italy therefore benefited from the ECB’s expansionary policies introduced in 2015: slashed interest rates, quantitative easing, etc. Loosened monetary policy stimulated the French and Italian economies, drove up inflation and made their debts more sustainable.

This puts them on the same side of fiscal and budgetary debates in the eurozone. The austerity measures introduced after the 2008 financial crisis and the subsequent 2011 eurozone crisis significantly limited fiscal flexibility when struggling southern states needed it most. Austerity came from the Stability and Growth Pact, which ordinarily compels EU members to limit their annual deficit to 3 percent of their GDP and caps public debt at 60 percent. (These are the provisions slated to be reinstated next year.)

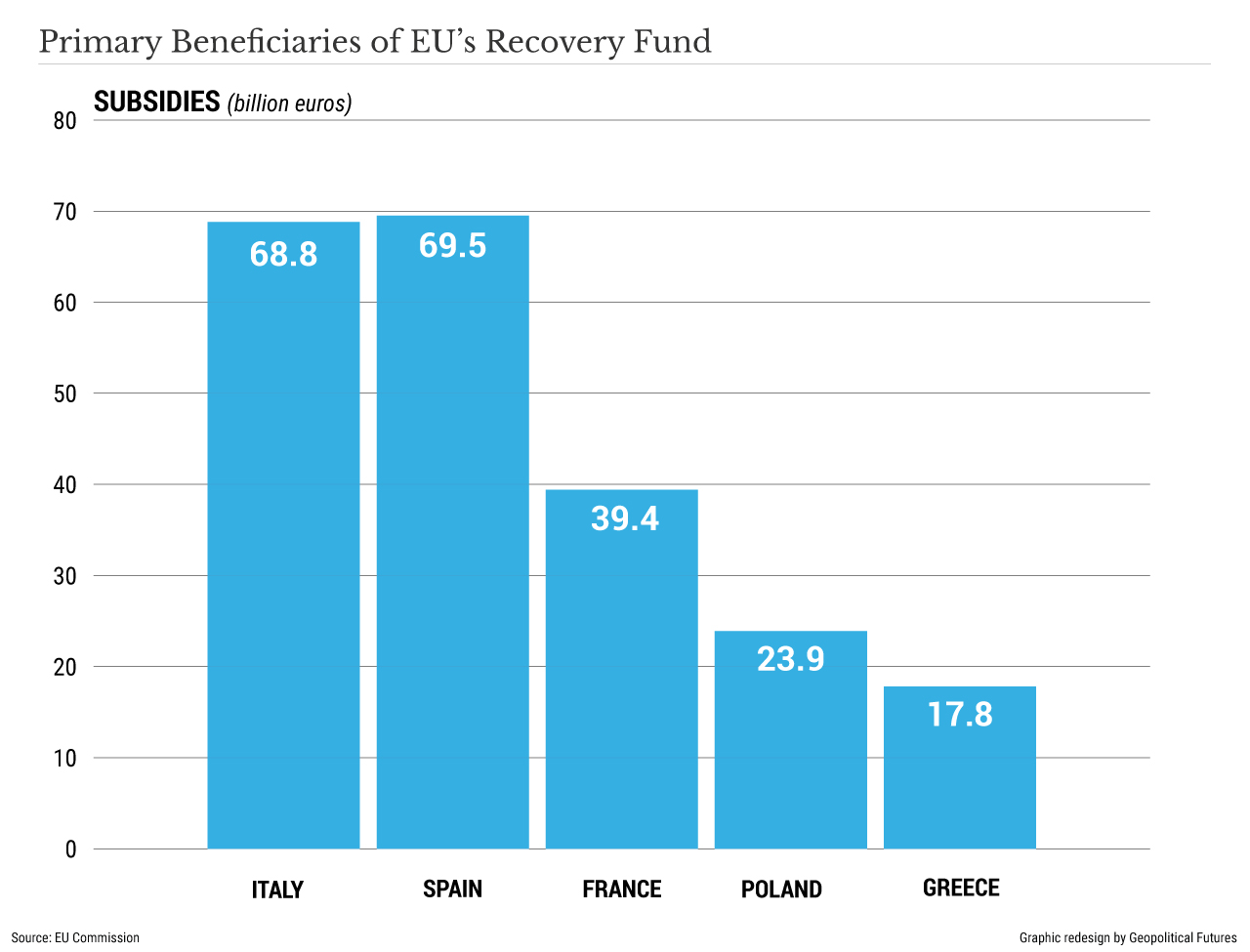

It’s little wonder, then, that Paris and Rome are dead set against austerity. Their economic stability, and thus their domestic stability, depends on substantial government spending and welfare state measures. It’s also little wonder that they were among the biggest beneficiaries of Next Generation EU, the extraordinary recovery plan meant to help EU states recover from the pandemic. Both have expressed the need to turn the NGEU into a permanent mechanism contributing to the creation of a de facto transfer union among European states.

This is why the French and the Italian representatives to the ECB board warned the bank against rushing to ending its expansionary programs and its low interest rates despite soaring inflation in Europe. Italian and French officials have also stressed the need to reform budgetary rules in order to grant states more fiscal flexibility. France in particular has been one of the strongest supporters of the European banking union, the creation of a eurozone finance minister, and the de facto mutualization of eurozone debts through so-called Eurobonds. Rome has always backed France’s position regardless of who is in charge of the government.

Obstacles

Even so, there are several obstacles that will keep Italy and France from getting their way. For one thing, France and Italy may be the second- and third-largest economies in the EU, respectively, but the fiscally conservative countries they are going against include Germany, the EU’s strongest economy. Others such as Austria and the Netherlands advocate the need to return to fiscal rigor. Their governments were among the most reluctant to adopt the NGEU but were ultimately persuaded by Germany. Berlin feared that the most vulnerable EU states, if not properly financially supported, would have jeopardized the EU single market and the eurozone, the preservation of which is one of Germany’s most pressing goals. However, German public opinion is firmly against the bailing out of southern EU states. Making NGEU a permanent mechanism or creating a European transfer union is a non-starter for Berlin.

For another thing, given the recent inflationary pressure in Europe, the frugals’ representatives in the ECB board demanded that expansionary monetary policies like the pandemic emergency purchase program gradually end and that the ECB start to reduce the rate at which it purchases assets. Rising prices represent a potential danger for competitiveness, especially for Germany since almost half of its GDP comes from exports.

A Franco-Italian alliance would not be enough to overcome the frugals. This is why France has tried to garner the support of other southern EU countries that share similar interests such as Spain, Portugal and Greece. They all face similar economic problems and support the same eurozone reform projects proposed by France.

But perhaps the biggest obstacles are the limitations France and Italy put on themselves. A bilateral alliance would focus on economic and fiscal measures but would not likely be applied to other fields like foreign policy. One of the main reasons for this is disagreements over how to engage in the Mediterranean, where Paris has been calling for a “more united” European stance against Turkey. It was a thinly veiled jab at Italy, which has been more ambivalent about Turkey because of its energy interests in the Mediterranean. Related to this issue was Libya. Rome supports the Government of National Accord led by Fayez al-Sarraj because it allows Italian energy company ENI to operate in its territories. (Ankara also supports the GNA.) France supports the Libyan National Army led by Khalifa Haftar.

However, the most pressing issue in Franco-Italian relations remains Europe, which is closely linked to domestic stability and economic recovery. Their rapprochement could widen an existing split in the EU, but more important, it could do likewise in the eurozone. The European Union is known for its ability to compromise, but it’s hard to compromise on long-term existential differences.

No comments:

Post a Comment