Saeed Ghasseminejad

Enrique Mora, the EU envoy coordinating the Iran nuclear talks traveled to Tehran recently in an attempt to convince the regime to return to the Vienna process.

The EU invested considerable political and diplomatic capital in the long process that led to the 2015 accord, formally known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). EU leaders had tried hard to convince former President Donald Trump not to abrogate the deal, and they have again invested considerable effort, since Joe Biden’s election, to serve as a middleman between Tehran and Washington. All of this diplomacy invites an economic question: What can the EU expect to gain if trade and investment become possible in Iran with the lifting of US sanctions?

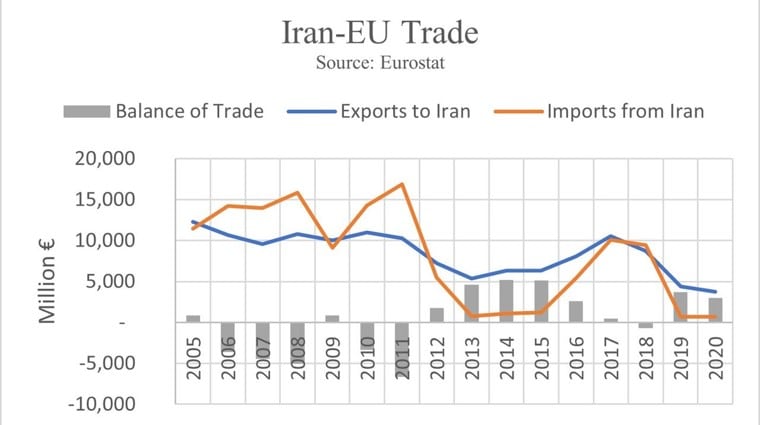

The history of Iran-EU trade over the last 15 years shows a downward trend, with a high degree of correlation with the severity of sanctions. When US-initiated secondary sanctions are in place, whether multilateral or unilateral, they quickly affect Iran-EU trade. EU states opposed the Trump administration’s unilateral maximum pressure strategy, but Trump’s sanctions had the same impact on Iran-EU trade as multilateral sanctions did prior to the JCPOA.

In no small part, Iran-EU trade is so sensitive to sanctions because the EU can quickly replace Iran with other trade partners, while Iran can not do likewise. In 2013, at the height of the Obama administration’s sanctions campaign against Iran, EU imports from Iran dropped to 751 million euros from their zenith of 17 billion euros in 2011.

In 2019, the first full year that Trump’s maximum pressure strategy was in place, EU imports from Iran slid to 680 million euros, down from 9 billion euros in 2018. EU exports, while reduced due to US sanctions, have shown less volatility. The EU’s 2013 exports plummeted to 5.3 billion euros from their high of 11 billion euros in 2010. These exports went back up to 11 billion euros in 2017 while the JCPOA was in effect, but in 2020 descended to 3.7 billion euros. Non-Iranian trade partners filled the gaps.

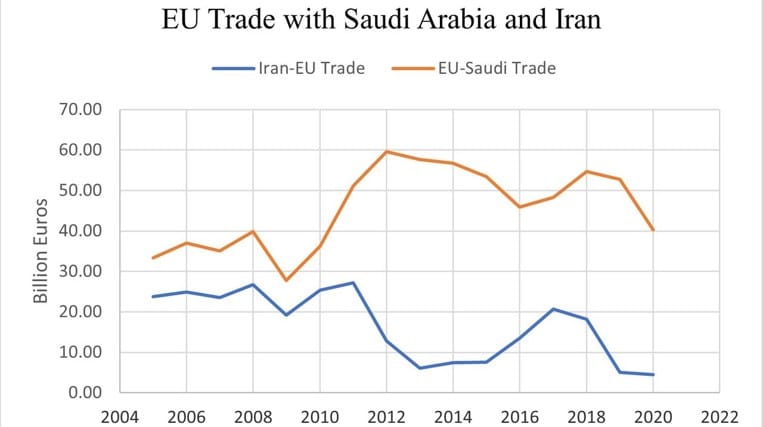

By contrast, trade between the EU and Saudi Arabia, Tehran’s chief rival in the Persian Gulf, benefits from diplomatic stability. Since 2005, EU-Saudi trade has enjoyed a general upward trajectory, even though it is sensitive to volatile markets for oil. However, the Saudis have managed to expand their non-crude exports to the EU. In 2020, 7.2 billion euros — 46 percent of Riyadh’s exports to the EU — were from non-crude oil, up from 3.84 billion euro in 2005.

The greater volatility of EU imports from Iran stems from the impact of sanctions on the import of crude oil. Iran’s non-crude exports to the EU are neither considerable nor growing. They still have not returned to their 2007 level of 1.7 billion euros, and in 2020 were slightly above 600 million euros.

European governments opposed Trump’s unilateral sanctions and tried to convince European companies to trade with Iran. However, the private sector defied Brussels and complied with Washington’s sanctions. Despite loose enforcement of US sanctions by the Biden administration, the data for the first seven months of 2021 show no significant increase in trade between the EU countries and Iran. During this time period, EU’s imports from Iran rose to 480 million euros, slightly higher than 440 million euros during the same period last year, while its exports dropped from 2.21 billion euros to 2.11 billion.

No comments:

Post a Comment