ETHAN LOU

One of the most reclusive and restrictive places in the world, North Korea isn’t easy to visit, but it’s not impossible. For the blockchain conference, there was an application process. The fee was €3,300 ($4,800), flying from Beijing—North Korea welcomes few foreigners directly, and most trips have to start from China, its ally and biggest trading partner. The bulk of the fee was to be paid in cash upon arrival, and €800 ($1,200) of it prepaid. The available payment methods? Either a wire to some obscure financial institution in Estonia or a transfer of Ethereum’s Ether, the most valuable cryptocurrency after Bitcoin. I chose the latter because it was less painful, and fortuitously for North Korea, Ether appreciated by as much as 50 percent in the ensuing two months, resulting in a 50 percent profit from simply doing nothing. All of that perfectly illustrates the curious link between North Korea and cryptocurrency, which critics say threatens global stability—a connection built entirely on what that dictatorship is and its place in the world.

Formed after the Second World War, North Korea has never played well with most of the world, pursuing nuclear weapons against the West-led order and being accused of rampant human-rights violations and criminal behaviour. The West’s response? Hit North Korea with economic sanctions, which in the postwar decades have become the favoured way to show displeasure. But that can be devastating to a country’s economy. If the international banking community shuns a country, it becomes hard for that country to send and receive payments and conduct trade. In 2016 and 2017 alone, the United Nations sanctioned North Korea more times than in the previous twenty years.

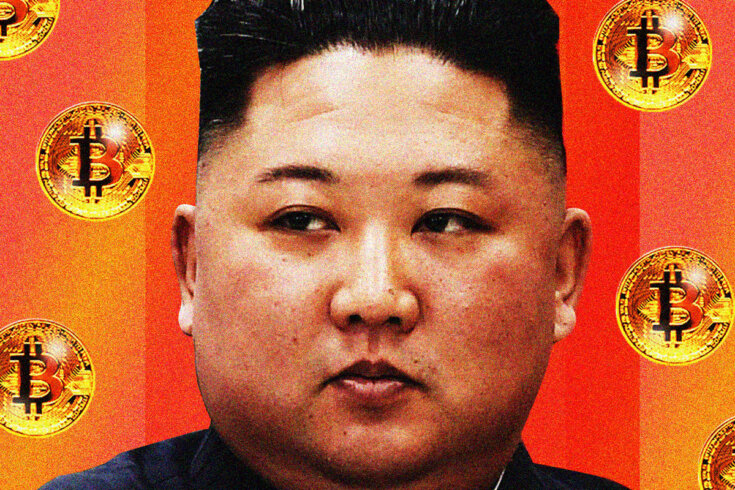

Enter cryptocurrency, which can be moved without centralized control and whose transactions can be difficult to trace. Theoretically, if used correctly and with the right infrastructure and resources behind it, cryptocurrency could help North Korea overcome sanctions. Since 2017, observers have increasingly said that the country was stockpiling cryptocurrency. According to a UN report from 2019, the country’s government hackers had by then amassed more than half a billion dollars in cryptocurrency over two years.

North Korean interest in cryptocurrency is also at least partly ideological. The idealized self-sufficiency that cryptocurrency grants, after all, is reflected in the country’s official state doctrine, Juche (the incompatibility of cryptocurrency ethos and the country’s broader communist ideology notwithstanding). In 2017, an article on the website of the government-controlled Kim Il-sung University, named after Kim Jong-un’s grandfather, stated that, in order to improve the country’s financial structure, it was vital to master cryptocurrency. Experts said that Kim Jong-un himself had given a thumbs-up to the blockchain conference we were all attending.

But, of course, all the information I knew at the time on North Korea and cryptocurrency had been observed from the outside. Much of what we think we know about the dictatorship comes from defectors and Japanese and South Korean intelligence, each with their own agendas. As well, lots of viral North Korean news can be traced back to unreliable sources. Kim Jong-un’s ex-girlfriend was reported executed. She later turned up on television, alive. International media once picked up the story of how Kim’s uncle was executed using 120 wild dogs—dramatic but ultimately proven false. What truly was happening on the ground in North Korea with respect to cryptocurrency? Some experts said the conference’s purpose was to send a message to the United States and its allies that North Korea could defeat sanctions using cryptocurrency. Analysts and law enforcement were expected to be paying keen attention to the event. It was a golden opportunity to see for myself what North Korea had been up to with cryptocurrency. I ended up, by all measures of that word, surprised.

IHAD THOUGHT that the blockchain conference was going to be a big event, but the day before we flew out, I found out I was one of only eight foreigners going. We flew to Pyongyang on Air Koryo, once the world’s only one-star (out of five) airline. Koryo was at one point banned by the European Union because its Soviet-era planes were too old. They still looked retro, with flight attendants wearing the high heels many other airlines had retired.

There is much about North Korea that you can never read in books or watch in the news, much you can never understand from afar. This became clear when I observed the problems experienced by a fellow attendee. He started taking pictures of the Barbie-like flight attendants and North Korean passengers wearing boxy suits and Kim Il-sung and Kim Jong-il pins. An attendant approached him and insisted he delete the pictures and show her that he had done so. Then, when we landed in Pyongyang, the man had his laptop taken away for images of his ex-girlfriend that the local authorities construed as porn. The North Koreans promised to give it back when we left, and they eventually kept their word. But it was a foreboding event. In that moment, it became clear that I had stepped into a different world.

On arrival, I discovered that the conference agenda had yet to be determined. The next day, two days before the actual summit, the attendees were asked to be presenters. While at least one among the eight was already supposed to be a speaker, most did not expect to be recruited. I was asked to prepare a presentation on blockchain in Asia. I declined. I was mindful of the geopolitical sensitivities, of how controversial it could be to be seen as giving technological aid to North Korea. I was there as a conference goer. To participate as a speaker was simply too risky.

For that reason, I will not be saying too much about my fellow attendees. I name only those who have already publicly said they attended: Christopher Emms, the organizer, a Brit with a background in finance; Italian information-security specialist Fabio Pietrosanti; and an American living in Singapore, Virgil Griffith, who worked for the Ethereum Foundation, the main force behind the blockchain platform. The rest were mostly assorted Europeans, the youngest of whom was my age. We had little in common other than the fact that we were all in North Korea, but that was enough, and we knew it. We happy few. That spring of 2019, beneath portraits of two dead Kims, we sat through an improvised two days of halting blockchain presentations.

In China, there’s a rent-a-white-person industry of sorts. It’s been declining, but it exists, especially in lower-tier, less international cities. White people are usually paid a couple hundred bucks, given some important-sounding title like “director,” and asked to give a speech or attend a fancy dinner, although some gigs are more creative. In 2017, a car-repair shop wrote an ad looking for westerners to “perform as mechanics.” The idea is that a white face conveys an international image. Property developers, for example, want to show their backwater towns as globalized cities. A white face also adds prestige. Having one makes a company seem connected and successful. The actual background of the hired foreigner does not matter. “Audiences are watching you for your skin colour, not for what you are doing,” American director David Borenstein, who made a documentary on the phenomenon, told the South China Morning Post. “It’s kind of like being a monkey in a zoo.” I felt similarly about my group’s presence at the North Korean blockchain conference.

The Koreans called us a “delegation,” to be trotted to the centre of the conference room and address about fifty locals. They gawked and laughed at three foreigners who, on the second day, showed up in freshly tailored Mao-style suits with Mandarin collars. We slept and dined in their finest places, but we had no idea who made up the conference audience as we were allowed no one-on-one contact. They probably had no idea who we were beyond what we said we were. We seemed to be just token foreigners.

There was nothing new discussed at the conference, no information presented that could not be found on page one of a Google search. The presentation materials, which had to be preapproved by the Koreans, were just publicly available research papers. I never got to hear from a single North Korean about the country’s alleged work or plans with respect to cryptocurrency.

Our North Korean minders said that the country did not know anything about cryptocurrency or blockchain, and there was definitely some truth to that. Even the name of the event had to be changed to “International Conference on Finance” because the organizers on the North Korean side deemed “blockchain” too alien. I talked to a restaurant server who did not even know the term Bitcoin. She had never heard of the word at all. I could not explain to her why I was in her country.

THE IMAGE OF North Korea that I’d gleaned from the widely circulated reports—using cryptocurrency to evade sanctions, hacking millions from exchange platforms—was nowhere in sight. In a meeting with one of the country’s biggest corporations, a senior executive told me that the unspectacular blockchain experiments his organization had undertaken amounted to the most advanced in the country. Wondering about the reports I’d read, I asked the company man what North Korea had done in cryptocurrency mining. He told me there was nothing. Mining is an electricity-intensive process, and the country, he said, scarcely had enough power for domestic consumption—which was not a lie. In the days before the conference, our minders brought us to a teachers’ college, and while we were there, the power went out. It also went out several times at my hotel, which was supposed to be Pyongyang’s best.

We think of North Korea as stuck in time yet constantly perpetuating great evil. But, if you’ve seen what I saw, that western view of North Korea—as backward yet sinister—seems quite contradictory. It’s hard to believe that the country is capable of anything at all. And yet, according to reports, North Korea has been not only stealing coins in South Korea but also generating new units through mining, the process of running servers to facilitate cryptocurrency transactions. North Korea has also allegedly been behind ransomware attacks—compromising victims’ computers and locking up their files until a specified sum has been paid, usually in cryptocurrency.

While North Korea kept its cryptocurrency ambitions hidden from plain view, what I did perceive while there was a constant reminder of the geopolitical tensions all around. The sanctions loomed large over our trip. A tragedy was still fresh in mind: Otto Warmbier, an American who was detained in North Korea, had died upon his return due to what his parents said was torture. With worsening tensions, insults like “dotard” and “rocket man” had entered the diplomatic lexicon. US president Donald Trump held two unprecedented summits with North Korean leader Kim Jong-un, all sound and splendour, signifying nothing, but they were high profile and thrust the country firmly into the zeitgeist.

Then there was the issue of China. Here, even service staff spoke pitch-perfect Chinese. Chinese electronics and Chinese cars—the shadow of North Korea’s uneasy elder-brother ally—were everywhere. Just like in the Korean War, which began in 1950, the peninsula was not just a battleground in itself but also a proxy arena for struggles between bigger powers. It was a powder keg. Analysts feared a nuclear crisis.

Against that backdrop, it would not be surprising if cryptocurrency and blockchain, mysterious technologies with a sometimes unsavoury reputation, were caught up in those global hostilities. Even as some locals were literally falling asleep during the conference, half a world away, there were those who sat up and paid attention. None of us knew then how vigorous that attention was—not until Thanksgiving 2019, when Ethereum’s Virgil Griffith, while flying from Los Angeles to Baltimore, was arrested for his alleged part in a “conspiracy” at the North Korean conference we had all attended. He was accused of trying to give the totalitarian state “technical advice on using cryptocurrency and blockchain technology to evade sanctions,” in violation of sanctions. If convicted, Griffith could face up to twenty years in prison.

But that was still months away when, on the overcast final night of the blockchain summit, we drank Chinese baijiu to mark the conclusion, readying ourselves to return to real life. With stars overhead cloaked against the black Pyongyang sky, I didn’t doubt that I had been shown only a small, curated part of the country. Perhaps it had all been an act—just as how the foreigners at the conference were made to put on a hastily cobbled show of blockchain for those assembled. A performance within a performance within a performance.

No comments:

Post a Comment