China’s economic and political footprint has expanded so quickly that many countries, even those with relatively strong state and civil society institutions, have struggled to grapple with the implications. There has been growing attention to this issue in the United States and the advanced industrial democracies of Japan and Western Europe. But “vulnerable” countries—those where the gap is greatest between the scope and intensity of Chinese activism, on the one hand, and, on the other, local capacity to manage and mitigate political and economic risks—face special challenges. In these countries, the tools and tactics of China’s activism and influence activities remain poorly understood among local experts and elites. Both within and beyond these countries, meanwhile, policy too often transposes Western solutions and is not well adapted to local realities.

This is especially notable in two strategic regions: Southeastern, Central, and Eastern Europe; and South Asia. China’s economic and political profile has expanded unusually quickly in these two regions, but many countries lack a deep bench of local experts who can match analysis of the domestic implications of Chinese activism to policy recommendations that reflect domestic political and economic ground truth.

To address this gap, the Carnegie Endowment initiated a global project to better understand Chinese activities in eight “pivot” countries in these two strategic regions.

The project’s first objective was to enhance local awareness of the scope and nature of Chinese activism in states with (1) weak state institutions, (2) fragile civil societies, or (3) countries where “elite capture” is a feature of the political landscape.

Second, the project aimed to strengthen capacity by facilitating a sharing of experiences and best practices across national boundaries.

Third, the project sought to develop policy prescriptions for the governments of these countries, as well as the United States and its strategic partners, to mitigate and respond to activities inimical to political independence or well-balanced economic growth and development.

To establish a comprehensive picture of China’s activities and their impact, this project dug deeply into Chinese activism in four case countries in each region—eight countries in total.

We began by holding workshops, so that influencers across countries could share experiences and compare notes. Invited participants included policymakers, experts, journalists, and others—all with deep local knowledge, steeped in their countries’ politics, economies, and civil societies. In Europe, the four countries were Georgia, Greece, Hungary, and Romania, and in South Asia, Bangladesh, Maldives, Nepal, and Sri Lanka. Cross-national discussions among these regional participants aimed to raise awareness, discuss the implications of China’s growing activism in their countries, and compare notes on the diverse ways in which these various countries had managed the rapid influx of Chinese capital, programs, people, technology, and other sources of influence.

After holding several workshops for each region, Carnegie scholars conducted extensive interviews and a comprehensive review of open-source data and literature on Chinese activities—including extensive media monitoring in local languages, from Bengali to Nepali, Georgian to Greek. These deep dives aimed to measure Chinese influence along three dimensions:

(1) Chinese activities that shape or constrain the choices and options for local political and economic elites;

(2) Chinese activities that influence or constrain the parameters of local media and public opinion; and

(3) China’s impact on local civil society and academia.

The first of these three dimensions is important because China’s sheer size means that it will inevitably play a role in these two strategic geographies. China is the world’s largest trader and manufacturer—and it sits on a significant pool of foreign exchange reserves and capital that countries in all three regions will invariably wish to tap. For this reason, these surveys aimed to identify, distinguish, and analyze only those specific activities that could constrict options, reduce the scope of choice, and reward a narrow interest group or elite.

The second of the three dimensions is crucial because China frequently couples its use of economic and political carrots and levers to broad-ranging public relations outreach. When China floods a country not just with investment but also with strategic messages designed to influence public opinion, there is often little space left for counter-narratives, especially in countries that lack independent media or have weak civil societies.

The third of the three dimensions is critical because in the most vulnerable countries of these two regions, civil society and academia are often too fragile to provide balanced coverage of the activism of external powers. In some cases, Chinese funding and so-called united front tactics have shaped domestic narratives.

Beijing, like other outside powers, cultivates friendly voices in nearly every country. But in some countries, there are few counterweights.

By exploring all three dimensions of Chinese influence simultaneously, Carnegie’s initiative has aimed to generate a clearer and well-balanced picture of Chinese activism and messaging in Europe and South Asia, while fostering a cross-national network of influencers who will continue to compare notes, learn across national boundaries, and spur a genuinely regional conversation about China’s rise and its far-reaching implications.

Erik Brattberg

Director, Europe Program and Fellow, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

Evan A. Feigenbaum

Vice President for Studies, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

SUMMARY

The Carnegie Endowment project “China’s Impact on Strategic Regions” comes at a time when states across several regions of the globe are experiencing China’s increased involvement in their polities, economies, and societies, and the consequences that such engagement brings with it. Over the last decade, China has developed a greater variety of interests and more connections than ever with countries, including in parts of Europe and South Asia. With these new channels of influence, it has developed expectations of exceptional consideration for its interests and is willing to exercise pressure in its pursuit for special treatment.

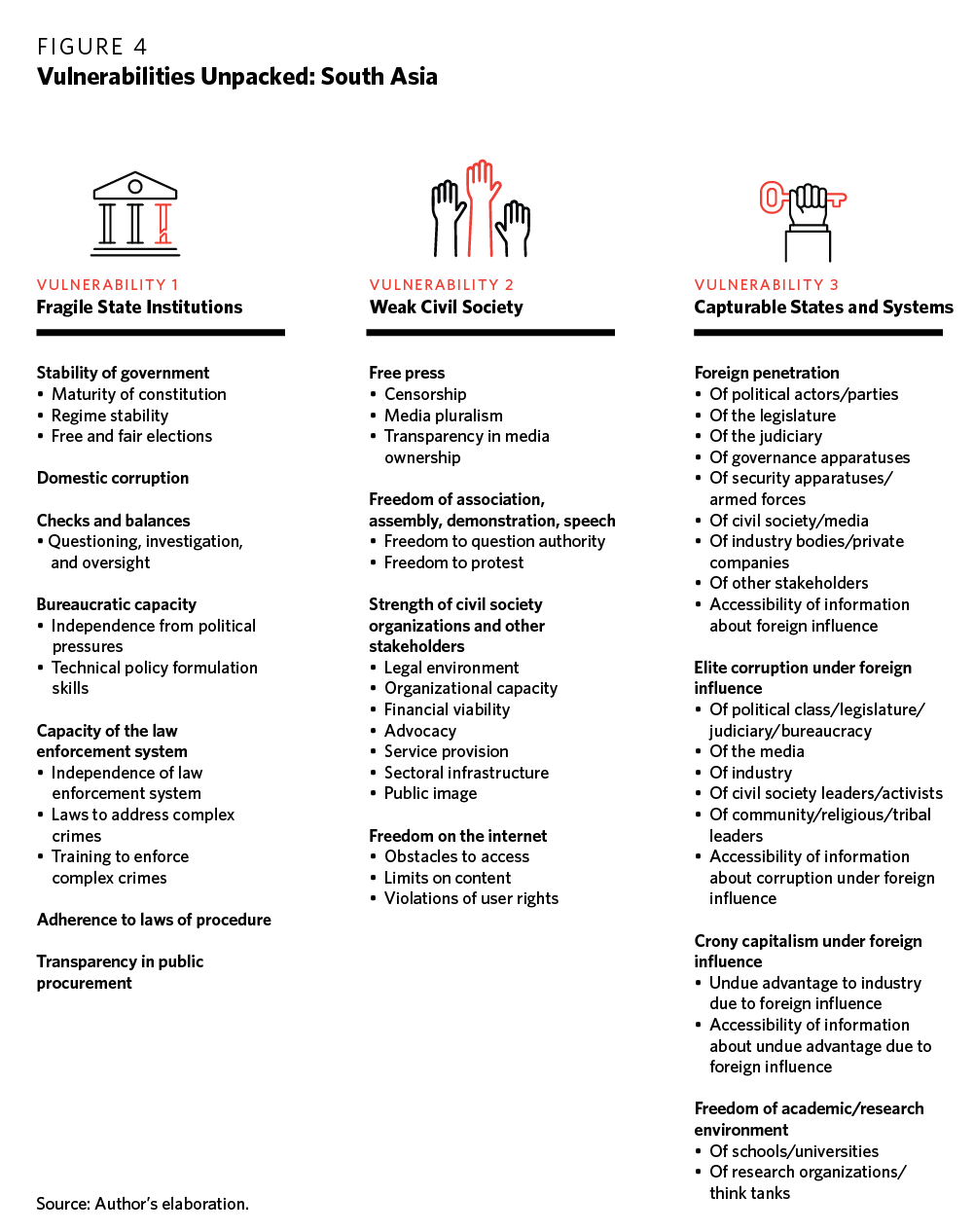

This paper builds on the research carried out through focus groups, extensive interviews, and detailed archival analysis and media mapping in four South Asian states—Bangladesh, Maldives, Nepal, and Sri Lanka—to learn from their rapidly evolving relationships with China, as well as explore the impact of Chinese influence cross-nationally and comparatively. All four countries have distinctive vulnerabilities. In some, state institutions are brittle. In others, civil society provides an inadequate check on the actions and powers of the state. Elsewhere, elites are prone to capture, including by external actors, such as China and its proxies. The study attempts to make sense of deepening Chinese activism by framing it in terms of the impact it has on the vulnerabilities in these states.

The paper aims to understand how China leverages specific vulnerabilities in these four states for its interests; how these vulnerabilities can be remedied; and how the states can share and learn from each other’s experiences to strengthen their individual and collective hand. Ultimately, the paper hopes to offer policy recommendations that aid the countries in discouraging unproductive Chinese actions and influences, while engendering the kind of engagement that is in their interest. The recommendations are also directed toward the United States and its strategic partners to help strengthen these states’ independence of action, bargaining power, and development.

CHINA’S GOALS

China’s main asset is its economic levers of influence, and Chinese actors are proactive in wielding these.

China is helping to construct mega infrastructure projects in every country in the region, in most cases with money that it has lent them. Its loans to Sri Lanka were at $4.6 billion in 2020, and the overall figure for Maldives is believed to be between $1.1 billion and $1.4 billion. These economic engagements serve Chinese strategic ends and help expand its influence in a region that has traditionally been considered India’s strategic backyard. Chinese actors are proactive in seeking opportunities, often approaching public or private stakeholders with suggestions for engagement, and timing project completion to coincide with upcoming elections. This earns them goodwill and increases the possibility of getting projects going.

China’s tools of influence are becoming much more diverse.

China’s tools of influence are varied and are wielded depending on the extent of its engagement in a country, on the robustness of that country’s institutions, and China’s personal relationships with key regime actors. These can be in the form of incentives or threats, used to deter or compel both state and nonstate actors in focus countries. Sometimes, coercive threats are used to lead local actors such as journalists to self-censor. At other times, blandishments and incentives such as buying advertisements, offering collaboration for a media outlet with the embassy, and so on are used to evoke compliance.

There is no “debt trap” in the four countries.

The commonly heard narrative of China practicing debt-trap diplomacy—a practice of offering easy money for unviable projects with the aim of gaining control of assets—does not hold in the four countries studied. Sri Lanka, most often cited as an example of debt-trap diplomacy, has an overall debt management problem. Studies in 2020 put Sri Lanka’s external debt to China at about 6 percent of gross domestic product (GDP). Other countries like Nepal and Bangladesh have been prudent in choosing their funders and methods of financing, often choosing traditional multilateral institutions or other bilateral lenders as partners.

Countries are learning from each other and changing how they exercise agency as a result.

In what is perhaps the most key finding from the project, stakeholders that were engaged highlighted their awareness about the negative consequences of Chinese engagement, as well as their willingness to avoid them. Correspondingly, state actors in the focus countries have exercised their agency in keeping their national interest in mind while dealing with China. This includes rejecting specific projects found to be untenable. Elsewhere, political parties have resisted giving in to China’s attempts at increasing engagement with them. In many instances, it is the governments in the states under study that have pulled China closer when they see clear benefits in cooperating—China can provide domestic political advantage ahead of elections, as well as deliver public works and other benefits to constituents.

China and its partners are still having teething trouble—for now.

China is a relatively new entrant to South Asia and is yet to clearly understand the institutions and organizational cultures of the focus countries. Likewise, the countries under study are still figuring out how Beijing thinks. These divergences account for the dissonance and diplomatic faux pas that are often visible. However, both sides are acutely aware of what they mean to each other, and keen to learn to work in the interest of the broader relationship.

India is still a more significant strategic player than China.

India continues to be the state with the most influence on the choices, interests, and conduct of the countries under study. Due to India’s historical, political, and social connections with these countries, there seem to be limits to how deeply entrenched China can become. However, the balance is gradually shifting toward China, for the role it can play as a developmental partner as well as a balancing factor against the regional power, India. Moreover, India’s close presence in their social, political, and economic lives also leaves it open to heightened levels of criticism, including allegations of meddling.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR THE UNITED STATES AND ITS STRATEGIC PARTNERS

Consistency is the key to China’s regional engagement; it should be key to the United States’ as well.

Steady engagement from the United States and its partners is still very much desired by all four of these South Asian states. These expectations, and the China challenge, can be met with a consistent presence and a long-term policy for the region, as opposed to the current perception of piecemeal and fleeting engagement. The first Quad summit’s decision to focus on vaccines, emerging technologies, and climate—three areas where China has made a big play to support South Asia—is useful in this regard.

Chinese projects focus on what the four states are perceived to need—so should U.S. engagement.

Like China, the United States needs to marry its capabilities and proposals with the development priorities and domestic needs of the four South Asian states. Connectivity and infrastructure projects are at the top of the wish list for all South Asian states and have become a key area of cooperation with China. To increase their profile in the region, the United States and its partners must pay attention to what the countries are asking for. The Build Back Better World initiative announced at the June 2021 meeting of G7 leaders is a productive step in this direction. As countries in the region transition to middle-income status and become ineligible for much of concessional assistance, the United States could use its influence in Western multilateral organizations to help these states develop alternative avenues for development assistance.

De-hyphenate U.S. engagement in the region from the Chinese question.

It would be prudent to pitch American assistance on its own merits and intrinsic value. It should be delinked from a broader anti-China thrust, and it should not be held hostage to the focus countries tempering their relationships with China. As small countries, it is unlikely that Bangladesh, Maldives, Nepal, or Sri Lanka can afford to explicitly choose among relationships with bigger powers. Any sort of conditionality reduces the avenues for cooperation. Communicating a positive agenda, not just a negative one, will win greater favor among governments, businesses, and the public.

Acknowledge domestic drivers and build capacity to reduce space for China.

The focus countries find China’s approach of noninterference favorable. One way the United States can circumvent being seen as interfering when it brings its assistance to the table with governance conditionalities is to build domestic capacity and strengthen civil societies in these focus countries. All four states in this study have media outlets and civil society organizations that have been focusing on questions of good governance. The United States can identify and equip them with grants and training to enable them and their audiences to ask tough questions and ask for transparency. In doing this, the pressure on governments to do better comes from within rather than without.

INTRODUCTION

In May 2021, Li Jiming, the Chinese ambassador to Bangladesh, used a conversation with journalists to caution the country against joining the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, or “Quad”—the informal grouping of Australia, India, Japan, and the United States that some in Beijing view as a prospective anti-China alliance. “Relations with China will be damaged if Bangladesh joins the Quad,” he warned.1 Foreign Minister A.K. Abdul Momen responded within a day, reminding China that Bangladesh was free to make its own foreign policy choices and to pursue alignments and relationships in its interest. He also confessed to some surprise that Beijing would wade into the internal choices of another country.2

Bangladesh should not have been so surprised. The reality is that China has been emboldened to assert its interests in South Asia more directly because of profound changes in its relationships with states in the region. Over the past decade, it has developed a greater variety of interests and more connections than ever. In parallel, China has developed more channels of influence as well as a greater expectation of deference to its interests and a greater willingness to exercise pressure in their pursuit.

Over the last decade, China has become far more attentive to its South Asian periphery, moving beyond commercial and development engagements to more far-reaching political and security ones.3 However, most analyses of these changing parameters of engagement have focused on the Chinese end of these relationships, and too often analytical attention is limited to examining specific infrastructure projects or investments under Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). This has left an incomplete picture of Chinese engagement because it misses the degree to which South Asian states are trying to manage and mitigate the impacts of Chinese influence that they view as inimical to their interests, even as they continue to develop political, military, and especially commercial ties with Chinese actors.

This paper is part of a multiregion Carnegie Endowment project, “China’s Impact on Strategic Regions.” It uses four cases—Bangladesh, Maldives, Nepal, and Sri Lanka—to examine not just the dynamic contours of China’s relationships with states in South Asia but also what can be learned from exploring Chinese influence cross-nationally and comparatively. The four countries have distinctive vulnerabilities. In some, state institutions are brittle. In some, civil society provides a weak check on the actions and powers of the state. In some, elites are prone to capture, including by external actors, such as China and its proxies.

The goals of this paper are threefold: to explore how China has leveraged specific vulnerabilities in these four South Asian states in pursuit of its interests; how these vulnerabilities can be plugged; and how sharing experiences among these four states could help them to strengthen their individual and collective hands, ensuring productive Chinese engagement in their interest while discouraging or mitigating the effects of unproductive Chinese actions and influences.

Ultimately, the paper aims to help strengthen local capacity through policy recommendations that could help these four countries mitigate and withstand the destabilizing elements of Chinese engagement while channeling Chinese energies in directions that support their interests. The study’s policy prescriptions are directed not only at each of the four countries but also to the United States and its strategic partners to help strengthen these states’ independence of action, bargaining power, and development.

ANALYZING THE SOUTH ASIAN SETTING

The four countries considered in this paper are not precisely alike. Neither are China’s relationships with them. For example, Maldives and Sri Lanka have been extremely receptive to Chinese loans for infrastructure projects. Bangladesh and Nepal, by contrast, have preferred alternative models to finance their development needs. In Bangladesh, China has emerged as the primary supplier of military hardware—a relationship that is not replicated in the three other countries. In Maldives, Nepal, and Sri Lanka, political actors with clear pro-China leanings have emerged, but not in Bangladesh. It is important, therefore, not to overgeneralize about the region. But, although the four countries are different, each is vulnerable in some way. And, above all, countries with such vast gaps in capacity invariably face challenges as they engage with China.

In this context, it is important to study the relationships of these countries with China individually or through a particular thematic lens such as infrastructure finance. However, examining the cases comparatively and comprehensively offers a more granular understanding. This paper, first, explores how each country measures on three axes of vulnerabilities—the comparative strength of state institutions, the robustness of civil society, and the dynamics of prospective elite capture. In examining state institutions, the study looks at how each state vets or monitors Chinese economic or political activities. Its analysis of civil society focuses especially on whether and to what extent the media and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) identify and expose irregularities. It explores potential elite capture by tracking foreign penetration of and influences on each national elite.

Second, the study looks at the gaps in comparative analysis of the four countries.4 There are indications that each one’s main political, commercial, and social actors are aware of the increasing intensity and complexity of Chinese operations across the region, and that they are learning from some aspects of each other’s experiences. However, much of this learning takes place passively—watching closely what has happened in a neighboring country, drawing lessons, and trying to avoid making the same mistakes. As an adviser to the prime minister of Bangladesh notes, “we have learned from Sri Lanka’s [experiences with Chinese export investments], we have learned from [the same in] Djibouti.”5 More could be learned from a more active sharing of experiences by stakeholders in these countries. This second section of the paper provides them with suggestions for how to do so.

Third, the paper explains what is actually happening in China’s relationships with these countries across a spectrum of political, economic, military, educational, and social issues. This section of the study draws especially on the insights of a network of influencers and experts from each of the four countries, as well as extensive interviews, focus groups, and other forms of stakeholder engagement. Over the course of this one-year project, the Carnegie Endowment assembled this network whose members straddle major sectors, including the government, political parties, the diplomatic service, media, chambers of commerce, industrial interests, academia, think tanks, the civil service, and nongovernmental organizations. The aim was to gain a whole-of-society understanding of dynamic attitudes toward China in and across the countries. To the latter end, the Carnegie Endowment brought together some of these stakeholders from different countries, facilitating comparative discussion and a sharing of experiences and ideas.

Fourth, the paper compares what is happening in the four countries by triangulating insights from this network with primary and secondary research, media monitoring, and deep analytical dives into all aspects of their relationships with China.

For each of the four countries, the paper poses six questions:

What is the underlying strategic logic and objectives that drive China’s activities?

What vulnerabilities and weaknesses within each state has China been able to leverage, with what set of tools, and in what combination?

How effective are the various Chinese influence activities, and what impact do they have on local institutions and on public and elite perceptions of China?

What are the actual or prospective threats to the interests of the United States and its strategic partners?

Has the coronavirus pandemic been an inflection point that either bolsters or weakens Chinese influence?

How have the four countries managed and mitigated their vulnerabilities and what lessons can their neighbors learn from their distinctive experiences?

The Carnegie Endowment held closed-door workshops with domain experts from the focus countries between October and December 2020 and remained engaged with the network afterwards. The formal sessions were organized thematically and included some forty participants.

Between January and May 2021, the author undertook forty digital and phone interviews as well as primary research. This helped to triangulate data collected from the workshop discussions and to develop country analyses. This phase included a deep dive into open-source information from policy papers, academic research, private and public company websites, social media posts, official government documents, and statements in Bangladesh, India, Nepal, China, Sri Lanka, Maldives, and the United States. It also included archival research of news articles in the Bangla, Chinese, English, Nepali, Sinhala, and Tamil languages dating from 2013 to 2020. Together, these provide a more complete picture of China’s rising influence than can be gleaned only from English-language sources.

CHINESE ENGAGEMENT IN SOUTH ASIA: THE STORY SO FAR

In recent years, the most powerful sources of Chinese influence in the four South Asian countries surveyed have been commercial and financial.6 This is reflected in high-value project finance and operations partnerships, not least for the Hambantota and Colombo port projects in Sri Lanka and the Padma Multipurpose Bridge Project in Bangladesh. Without exception, the governments of the four countries have described China as a crucial development partner, either as a funder or in providing technological and logistical support.7 Additionally, it is the biggest trading partner in goods for Bangladesh and Sri Lanka, and the second-largest for Nepal and Maldives. Chinese investors have been the largest source of foreign direct investment (FDI) pledges to Nepal for six consecutive years till 2020–2021, with more than half of the country’s total FDI in the 2018–2019 fiscal year.8 However, the economic element is increasingly intertwined with political, government, and people-to-people aspects of these relationships.

Chinese tourists have become an important driver of growth for all four countries, with active encouragement from the authorities in China. For example, in 2019 before governments shut down international travel in response to COVID-19, the number of Chinese tourists in Nepal increased by over 11 percent year-on-year. They were no doubt encouraged by the Chinese ambassador who released a professionally shot set of photographs of herself visiting the country’s tourist attractions.9 On the other hand, in Maldives, leaders of the tourism industry believe that a lack of government backing in China stifled the flow of Chinese tourists to the country, which has been open to international travelers even amid the coronavirus pandemic since mid-2020.10

Educational partnerships have expanded too. Several Confucius Institutes have opened in Bangladesh in quick succession. In Nepal, multiple schools have made Chinese-language courses compulsory after the Chinese government offered to cover the salaries of the teachers involved.11 In Bangladesh, journalists have been awarded one-year, all-expenses-paid fellowships to Chinese institutions, and multiple newspapers have worked with the Chinese embassy to coordinate roundtables on the benefits of the BRI for the country.

The International Department of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has assiduously built alliances with political parties in the region. It has organized virtual seminars and workshops with members of the ruling parties in Nepal and Sri Lanka to discuss the relationship and avenues of cooperation between the parties.12 In Bangladesh, the ruling Awami League signed a memorandum of understanding (MoU) aimed at enhancing cooperation with the CCP in the presence of Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, the party president.13

The CCP has also mobilized another of its arms in building influence in the region in recent years. Several ambassadorial appointees to South Asia have worked extensively in the United Front Work Department (UFWD) of the CCP, and not necessarily in the diplomatic corps. The UFWD operates to influence political, economic, and intellectual elites in other countries; in the current context, that involves forging a narrative that paints China as a key player in the global order and a partner for the future. Ambassador to Bangladesh Li Jiming and former envoy to Sri Lanka Cheng Xueyuan trace their careers back to the UFWD. Among others in the region, Nong Rong, ambassador to Pakistan is also known to have a background in the department.

The pandemic has created opportunities for China to work directly with the four countries in new ways—on the provision of medical equipment, biomedical expertise, and capital for coronavirus-related needs.14 China supplied testing kits, personal protection equipment, and medical supplies to the four countries in 2020. It extended a $500-million loan to Sri Lanka and sent a team of experts to Bangladesh to treat patients and train medical professionals. In 2021 it has supplied Sinopharm vaccines to the four countries.15 With the crisis exposing shortcomings in public healthcare capacities, it is likely that in a post-COVID-19 world, when South Asian countries talk about infrastructure, they will mean hospitals and laboratories as much as ports and highways. China will be eager to step in. Its technological and scientific collaborations, even if still inchoate, will offer options through the Health Silk Road.16 A build-out of telemedicine will require advanced 5G technologies, opening opportunities for Chinese companies, including its national telecoms champion, Huawei.

These developments demonstrate that China’s presence in South Asia is no longer predominantly economic but involves a greater, multidimensional effort to enhance its posture and further its long-term strategic interests in the region. But this increasing Chinese engagement and influence will likely exacerbate domestic divisions in all four states. It will create stakeholders in close relations with China, which has the potential to pit political and commercial elites against each other. In the case of countries with fragile institutions, underdeveloped civil society, or elites susceptible to capture, this may eventually weaken the state itself. For now, however, in most of the four states, China is still largely viewed as a partner that can assist with developmental needs—and it will not be easy for the United States to contest this. Multiple stakeholders from the region say that U.S. interest in and engagement with smaller South Asian countries is viewed locally as being sporadic at best. China, on the other hand, is perceived as a player with a plan. Moreover, despite questions about and criticism of its presence, Chinese actors have taken tangible steps to build confidence in their resolve and staying power.

BANGLADESH

The relationship between Bangladesh and China took a few years to warm up, with the two countries establishing diplomatic relations only in 1976. However, by the time Bangladesh signed on to the BRI during Chinese President Xi Jinping’s visit to Dhaka in 2016, economic, security, and geopolitical necessities had ensured all-round engagement between them. The largest number of infrastructure projects developed with Chinese help in South Asia are in Bangladesh. At the same time, the relationship embraces elements of a strong security partnership. According to a 2020 report by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, Bangladesh is China’s second-largest buyer of military hardware globally, accounting for almost one-fifth of the latter’s total exports between 2016 and 2020. Chinese arms make up over 70 percent of Bangladesh’s major arms purchases.17 Between 2009 and 2011, this included tanks, rescue vehicles, radars, ships, missiles, and defense systems, costing approximately $546 million.18 In 2016, Bangladesh procured two diesel electric submarines from China for $186 million.19

Bangladesh prefers to buy Chinese weapons as they are cheaper than those of established arms-exporting countries in the West or of Russia, and also because China extends soft loans to make these purchases.20 Security-related cooperation extends to the police force. In 2018, the two countries signed agreements on law-enforcement training assistance and providing arms and ammunition to the national police.21 Beyond the technical benefits that accrue to Bangladesh, this security relationship—which is unique in a region that India considers its direct sphere of influence—also points at Dhaka’s dexterity in balancing its relations with China and India.

This balancing act extends well beyond security. China has been an ideal partner for Bangladesh to expand its manufacturing base to cater to diverse export markets, including the Chinese one, and to overcome infrastructure gaps through project finance and construction. Economic engagement is primarily in trade, infrastructure, and business-to-business partnerships.

China is not among Bangladesh’s top ten export partners,22 but it aims to remedy this with policies and preferences to bolster the latter’s export prospects. For instance, China has allowed 97 percent of Bangladeshi goods duty-free access to its domestic market since June 2020.23 More important, it is helping the country to diversify its export base and move its industry up the value chain.24 Bangladeshi entrepreneurs can procure Chinese manufacturing machinery at minimal interest and with substantial grace periods.25 During Xi’s visit to Dhaka in 2016, the two countries signed twenty-seven agreements under which China would lend $24 billion to Bangladesh for projects including coastal disaster management and a road tunnel under the Karnaphuli River, as well as help to strengthen production capacity.26 China is also directly setting up manufacturing industries in Bangladesh, located in special economic zones (SEZs) such as the Chinese Economic and Industrial Zone-2 in Chittagong.27 Bangladeshi companies have expressed a preference for joint ventures with Chinese ones as, beyond attracting investment and financing jobs, this helps to facilitate the transfer of expertise and technology.28 According to Bangladeshi entrepreneurs, investment from China comes in clusters, as an initial investment generally leads to follow-on joint ventures, eventually establishing an entire ecosystem.29

The energy sector has been the greatest recipient of such investment, with Bangladeshi companies establishing joint ventures with Chinese counterparts. The 1,320-megawatt Payra coal-powered plant, the largest power plant in the country, which came online in 2020, is brought up most often as an example of the success of the model. It was developed by Bangladesh China Power Company, which was created as an equal-stakes joint venture between China National Machinery Import and Export Corporation and Bangladesh’s North-West Power Generation Company.30 Apart from electricity generation, the project is expected to develop significant transportation operations and infrastructure facilities on site, building railroads and bridges, as well as developing and increasing capacity of the Payra port. Additionally, under a maintenance agreement with the Chinese company, Bangladeshi workers will be trained and technology to run the plant will be transferred in the five years after the start of operation.31 Beyond energy, China’s role in Bangladesh’s cluster-based-industrialization approach is visible in joint ventures set up for various projects in Purbachal, the country’s first “smart” city, which is being developed in the outskirts of Dhaka, as well as for an industrial zone in Chittagong for manufacturing firms and associated industries.32

China has emerged as a key partner in constructing and funding several infrastructure projects in Bangladesh, such as the Padma Multipurpose Bridge project, several expressways, and power plants.33 As of January 2021, the government was implementing nine crucial development projects, such as the multilane road tunnel under the Karnaphuli River, with Chinese loans and credits worth $7.1 billion.34 In 2018, the Dhaka Stock Exchange enlisted the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges as strategic partners to spur the digital modernization of the trading system. The Chinese exchanges are expected to help set up platforms with information about listed companies, to offer tools to analyze performance, and to help increase network security and provide digital surveillance software.35

Reflecting a trend that has become an essential component of Chinese engagement across the region, the two countries regularly hold business matchmaking exercises through trade bodies such as the Bangladesh-China Chamber of Commerce and Industry. China also exhibits a degree of sophisticated coordination that extends beyond these usual measures. Chinese businesses, the embassy in Dhaka, and other Chinese stakeholders appear to move in concert when reaching out to their Bangladeshi counterparts to gauge areas for new business opportunities, which can then be followed by informational seminars and offers of capital, all to set the ball rolling on a rapid timeline of just a few months from exploratory contact to contract.36

Rising economic engagement has been accompanied by heightened political coordination. The CCP has been reaching out and holding meetings with the ruling Awami League and its principal opponent, the Bangladesh National Party (BNP), since at least 2015.37 BNP Chairperson Khaleda Zia visited China in 2016, meeting Xi who thanked the party for actively helping develop China-Bangladesh relations.38 Members of the two parties have also visited China at the invitation of the CCP.39 In 2019, the Awami League signed an MoU with the CCP to study ways in which the two parties could learn from each other and collaborate.40

Although these elite and institutional relationships have made rapid progress, Bangladesh’s citizens generally still view China as a blank slate. Beijing’s representatives have tried to change this by partnering with think tanks, business houses, and newspapers. In 2015, Ambassador Ma Mingqiang sought to spread Chinese economic engagement in more diverse regions of the country by promising to help Bangladesh establish two SEZs at the cost of $4.5 billion.41 These are currently under development at Anawara, Chittagong, and Gazaria, Munshiganj, which decentralizes the Chinese presence. In 2018, at an event organized by the Bangladeshi conglomerate Cosmos Group, Ambassador Zuo Zhang detailed Chinese efforts to resolve the Rohingya crisis, an issue that is important not just to people in eastern Bangladesh along the Myanmar border but also at the national level.42

In recent years, China has launched multiple initiatives to develop what it calls “soft influence.”43 Friendship centers, cultural programs, and engagements with think tanks, newspapers, and local governments around the country are China’s channels of choice. In 2015, forty years of diplomatic relations were marked with a three-day cultural program on facets of Chinese life and society.44 That same year, Beijing proposed to establish the Bangladesh-China Friendship Exhibition Centre at a cost of $80 million.45 However, as one local stakeholder pointed out, it is China’s image as an economic powerhouse that is most attractive to the public—creating the impression of it as a “wealth creator” in Bangladesh and not merely an actor passing through the country temporarily.46

China has been using scholarships and educational exchanges to reach out to Bangladeshis, especially younger ones. It has emerged as the preferred overseas destination for Bangladeshi students. During Xi’s 2016 visit, an MoU promising scholarships to 600 students was signed.47 Beyond tie-ups with local universities, where it has opened Confucius Institutes, Beijing has offered Bangladeshi students summer courses in China and visits to the Confucius Institute head office.48 Chinese businesses have also been roped into such outreach programs. China Harbour Engineering Company Limited (CHEC), a Chinese state-owned enterprise (SOE) with an extensive presence across South Asia, has provided scholarships, new facilities, and school supplies to high-school students near one of its worksites in Chittagong.49

Public health was an area of cooperation even before the COVID-19 pandemic. A Chinese naval hospital ship made a port visit at Chittagong in 2013, where it provided medical services.50 In 2015, China provided equipment amounting to $4.1 million to the Health and Family Planning Ministry.51 Since the beginning of the pandemic, it has been helping government as well as private entities with testing kits, protective suits, and other equipment.52 A team of medical experts was sent to Bangladesh in June 2020 to assist in managing pandemic response and mitigation measures.53 Help has been forthcoming from the Chinese private sector too—Alibaba, for instance, sent testing kits and masks to Bangladesh in April 2020.54 The China-backed Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank has so far approved $350 million in loans to Bangladesh to fight the pandemic.55 The vaccine relationship between the two countries hit a speed bump over co-funding of clinical trials of the Chinese Sinovac vaccine in 2020,56 but that seems to have been forgotten now, with Beijing gifting 1.1 million doses of Sinopharm vaccine in two tranches.57 Bangladesh is now reportedly exploring the possibility of co-producing Sinovac in the country, which would align with China’s growing image as a country that is producing wealth and helping Bangladesh move its industry into new areas higher up the value chain.58

Despite all of this rapidly growing engagement, there are elements of Bangladesh’s approach to China that have run into problems. The Rohingya conflict in Myanmar, which has led to an inflow of refugees in Bangladesh after sectarian conflict between Rohingya Muslims and Rakhine Buddhist communities, has been a cause of great concern for Dhaka. It views China as capable of exerting influence on Myanmar, and the two sides have discussed the issue at the highest levels when Sun Guoxiang, special envoy for Asian affairs from the Chinese Foreign Ministry, met Bangladesh’s foreign minister in April 2017.59 China has tried to mitigate any negative Bangladeshi reaction to its stance by providing Rohingya-related aid on multiple occasions. For example, in June 2019 the two sides exchanged letters on providing rice aid to the refugees.60 However, Bangladesh believes geopolitics has come in the way of China doing more to resolve the issue despite promises.61

NEPAL

Nepal is unique among the four countries studied because it borders the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR), and the fact that the Nepali people have been tied to Tibetans through bonds of trade, culture, and family for centuries. Beijing has been keen to leverage its relationship with Kathmandu to aid its own objectives in Tibet and with Tibetan diaspora communities that have left over the decades. Ahead of the Beijing Olympics in 2008, protests that broke out in the TAR were mirrored in protests in Nepal, which has a significant Tibetan refugee population. One Nepali stakeholder confirmed that Beijing was unhappy with the daily protests organized by the Tibetan community in Nepal at the time.62 Since then, it has pressured Kathmandu into significantly reducing the number of movement passes issued to Tibetan refugees. When Xi visited the country in 2019—the first Chinese leader in two decades to do so—a mutual legal aid treaty, agreements on border management, and even an extradition treaty were discussed.63

The most recent inflection point in Nepal’s relationship with China was in 2015 when India implemented an unofficial, months-long economic blockade to express its displeasure over citizenship provisions in the country’s new constitution. This led to a critical fuel shortage and choked relief material arriving in response to the debilitating earthquake earlier in the year. Most critically, the blockade reinforced the dangers of dependence on one dominant market and infrastructure link, cementing the sense among Nepal’s elites that the country would need to cultivate China to increase its options.64 This led the two countries toward a comprehensive transit and transportation agreement that came into effect in February 2020. Apart from sending a political signal to India, the agreement enabled landlocked Nepal, at least in theory, to end its sole dependence on India for goods and trade by giving it access to Chinese ports.65 While the economic viability of Chinese facilities as an alternative to Indian ports for the transshipment of goods to and from Nepal has been questioned, the agreement also marked the beginning of a period of greater political closeness between the CCP and Nepali leaders, then led by prime minister K.P. Sharma Oli from the Communist Party of Nepal-Unified Marxist Leninist (CPN-UML).

The two parties have coordinated closely on political and ideological issues. This has included high-level meetings such as one between Oli and the chairperson of Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, Yu Zhengsheng, in 2016.66 Symposiums, such as one on “Xi Jinping Thought” in September 2019, are regularly organized by the CPN-UML and attended by high profile Nepali and Chinese leaders. The CCP regularly funds visits for members of political parties across the spectrum, from leaders to grassroots-level cadres.67 In May 2021, in a meeting attended by representatives of major Nepali political parties, the International Department of the CCP Central Committee proposed providing COVID-19 assistance through political parties in the country.68

China clearly accords considerable significance to having an ideologically aligned counterpart in Nepal’s power structure, and its current ambassador, Hou Yanqi, has been especially active in the country’s party politics. As rifts within the CPN-UML surfaced in early 2020, Hou met with top party leaders and urged them to stay united.69 Near the end of the year, as the party finally split, a team led by the vice minister of the International Department of the CCP, Guo Yezhou, met with President Bidya Devi Bhandari and CPN-UML leaders to bolster the ambassador’s attempts to avert the political crisis and forestall the party split.70

Increasing cooperation between Nepal and China in multiple areas is not just the product of ideological affinity between the communist parties of the two countries. It is also influenced by the reality of public support for the relationship in the post-blockade period and the elevation of China as a viable development partner, especially after Nepal signed onto the BRI in 2017. There has been growing admiration for China’s growth story and talk of China as a model of political and economic governance. The two countries have signed several agreements on legal issues including boundary management, mutual legal assistance in criminal matters, and cooperation at the attorney general level.

Infrastructure features heavily in the relationship. Even as ratification of the country’s compact with the U.S. Millennium Challenge Corporation’s (MCC) has run into trouble in parliament,71 Nepal has sought Chinese aid for major projects such as the Pokhara International Regional Airport, a cross-border optical fiber link, and the upper Marsyangdi Hydropower Station. The Kerung-Kathmandu cross-border railway project is one of the most crucial ones underway. When completed, it is expected to facilitate Nepal’s connectivity with the rest of the world through China’s road network. As Hari Prasad Bashyal, the consul general of Nepal in Lhasa, noted in 2014, “The expansion of railway networks will help develop trade, business, and tourism along with building relations at the (people-to-people) level between the two countries. The Chinese have shared that they have been considering our request to expand the railway networks to Nepal.”72

As in Bangladesh, China has facilitated technology transfer to Nepal, creating the perception and reality of aiding wealth creation and expanding employment. Emblematic of this is the rising number of joint ventures such as Hongshi Shivam Cements—a combined investment of $333.6 million into a cement factory that aims to produce 12,000 tons of cement daily and employ 2,000 Nepali workers.73 Trade relations have deepened in the past decade, with China accounting for 15.2 percent of Nepal’s imports as of 2019, up from 11.1 percent in 2012.74

Military ties and security exchanges with Nepal have been among China’s weakest in the region. However, new initiatives have been announced since 2017, including the annual joint military exercise Sagarmatha Friendship. Under a Joint Command Mechanism Agreement, the two countries have discussed joint patrolling of the border.75 During Xi’s 2019 visit, they also exchanged letters on providing border security equipment to Nepal.76

The COVID-19 pandemic has allowed China to advance its vision of a Health Silk Road in Nepal. By March 2020, Kathmandu had signed up to the “Chinese model against COVID-19” and started working with China on best practices to handle the pandemic, using Chinese testing kits and other equipment.77 In recent months, China has provided 1.6 million doses of the Sinopharm vaccine to Nepal, in addition to 1,500 oxygen cylinders as a grant.78 Nepal has also worked with China to promote traditional medicine, sending doctors to collaborate with Chinese practitioners.79 During Xi’s 2019 visit, the two countries agreed to cooperate in setting up a plant to produce Ayurvedic medicine in Nepal.80

China is also intent on public outreach. Thirty Chinese NGOs have been operating in Nepal under a framework agreement signed between the Social Welfare Council of Nepal and the China NGO Network for International Exchanges in 2018. Since 2017, Beijing has made offering Mandarin courses more attractive for schools by bearing the cost of employing teachers. Nepal’s premier higher-education institution, Tribhuvan University, among others, has signed agreements to establish Confucius Institutes.81 India has been the traditional destination of choice for Nepali students looking for higher education opportunities abroad, but China, through financial aid and scholarships, has increasingly made itself the destination of choice for those looking for technical skills and graduate degrees, in particular.82 For instance, in April 2015, China announced 1,500 scholarships for five years to facilitate the production of skilled human resources in Nepal.83 An estimated 6,400 Nepali students were studying in China by 2019.84 This has led to a steady infusion of technocrats and experts trained in China within the Nepali establishment, perhaps setting the pattern for a generation.85

Media cooperation and coordination of content has been increasing steadily too. Teams of journalists from both countries regularly visit each other for knowledge sharing and consultations.86 As far back as 2014, a team of Chinese journalists visited Nepal and was briefed by representatives of the Kantipur Media Group, one of the largest media companies in the country. China Radio International runs special Nepali programs as well as Chinese-language classes.87

China has used visits and consultations to expand institutional partnerships, such as one led by the Chinese Institute of Contemporary International Relations (CICIR), a think tank under the Ministry of State Security, just ahead of Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s visit in 2014.88 In 2016, a CICIR delegation met political leaders across the spectrum including then prime minister Pushpa Kamal Dahal, the former Maoist guerilla leader; CPN-UML Chairperson and former prime minister K.P. Sharma Oli; and Nepali Congress Chairperson Sher Bahadur Deuba, who is now serving his fifth term as Nepal’s prime minister, in preparation for Xi Jinping’s visit later that year.89 A widely read newspaper surmised that “China is monitoring Nepal’s political developments, activities of political parties, and international relations through its ‘think tanks.’”90

China has also leveraged environmental cooperation and humanitarian assistance and disaster relief (HADR) to enhance its relations with Nepal for some years. It sent a rescue team within 24 hours of the devastating April 2015 earthquake.91 It followed this up with geologists and seismologists to assess long-term measures.92 The show of solidarity reached its highest level with Foreign Minister Wang Yi visiting people displaced by the earthquake during an official visit.93 Beyond funds and human resources, China has directly participated in reconstruction; for example, by rebuilding the Durbar High School in Kathmandu, which it handed over in September 2020. The two countries also signed an agreement in 2018 under which China would provide HADR equipment to Nepal and help it establish an earthquake-monitoring project.94

SRI LANKA

Sri Lanka has been a flagship of Chinese economic engagement in South Asia since well before the introduction of the BRI in 2013. This has gradually expanded with direct investments and state-backed policy loans.95 The country features prominently in widespread narratives about China’s “debt-trap diplomacy,” with references to mega-projects such as the Hambantota Port and Colombo Port City project (also known as CHEC Port City) usually headliners. Colombo Port City is the largest foreign direct investment in Sri Lanka to date at $1.4 billion, and it promises to create 100,000 permanent jobs once completed.96 But the relationship with China is much more layered and diverse than this narrative suggests, with Sri Lanka exercising agency and intent.

The economic relationship has been highly personalized and tied significantly to China cultivating a relationship with the Rajapaksa family that was in power from 2005 to 2015 and has been again since 2019, this time with brothers Gotabaya and Mahinda serving as president and prime minister respectively. Throughout this period, questions have arisen about the viability of projects and about impropriety.97 But none of this has dislodged a relationship built on a foundation of political and strategic necessity. For Sri Lankans of diverse political stripes, China has been a useful ally—but this was especially true of the Rajapaksas, since many in the international community wanted to hold them accountable for human-rights violations committed during the civil war with the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), and especially in the conflict’s final phase in 2008 when Mahinda was serving as the country’s president.98 For China, the country has offered a friendly stepping stone from which to expand its presence in South Asia; it also represents a potential strategic asset sitting astride sea lanes, through which China’s energy supplies from the Middle East pass.99

China has thus not reached out to just the Rajapaksas. When their bitter opponent, Maithripala Sirisena, defeated Mahinda Rajapaksa for the presidency in 2015, Beijing quickly welcomed a delegation of ministers from his new government.100 In time, Sirisena’s government approved Rajapaksa’s China-funded projects that it had criticized and initially paused.101 In a message to Xi in 2017, Sirisena endorsed the BRI, expressing hope that it would usher in a new era of bilateral ties.102 China continues to emphasize that, irrespective of the political color of the government in Colombo, it views itself as a friend of Sri Lanka. Most recently, this has been reflected in the way that the Chinese embassy named and thanked parties and leaders individually for attending a commemorative event to celebrate the centennial of the CCP.103

The most significant decision concerning Chinese engagement in the country since the return of the Rajapaksas to power has involved passing a bill approving the CHEC Port City in May 2021. This was done just days after the Supreme Court pointed out that sections of the bill were inconsistent with the country’s constitution and required a popular referendum.104 Soon after the bill was passed, ministers released statements assuaging concerns about the port city being granted extra-constitutional status and highlighting investment opportunities that the project would bring to the country.105

China’s importance as a lender, investor, trader, builder, and partner is in part guided by Sri Lanka’s own economic progress that helped it graduate to lower-middle-income status in 2017, effectively disqualifying the country from much of the concessional assistance from the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and the World Bank.106 Because of this, Sri Lanka has felt compelled to diversify its sources of capital, turning substantially toward international bond markets. The share of Chinese loans, while growing, is still less than 15 percent of external debt.107 But the trajectory is clear: in 2019, $684 million out of a total of $1.1 billion in bilateral loans was from China. By comparison, Japan accounted for $178 million in loans and $9.4 million in grants.108 In 2020, loans fell to $720 million with China accounting for $324 million and Japan $161 million.109

Experts say that Sri Lanka needs to improve its debt management overall, not only with regard to China.110 However, for the time being, Beijing is a useful source of funding and its role as a capital provider is widely accepted. Part of the reason is that China has sold the story of its own success. Sri Lankan stakeholders note how government employees on visits to the country were extremely impressed by its economic progress and particularly taken by the message that, if China as a developing nation with its own history of a “century of humiliation” by outsiders could achieve this degree of prosperity, so could Sri Lanka as a postcolonial country.111 Additionally, in the popular imagination, China is seen as a consistent partner and not a fair-weather friend. Beijing’s decision to continue to develop projects in the country despite negative publicity over ones such as the Hambantota Port has strengthened this sentiment.112

A strategy of long-term commitment is evident when one looks at China’s outreach to the general public in Sri Lanka, which is motivated by the reasoning that the Rajapaksas will not be around forever.113 In recent years, it has started coordinating events and funding people-to-people organizations such as the Sri Lanka-China Friendship Association and the Sri Lanka-China Youth Friendship Association. Sri Lanka is increasingly popular with Chinese tourists, who accounted for a peak of 13.2 percent of all foreign tourists in 2016, up from 1.8 percent in 2010, before falling back to 8.8 percent in 2019.114 To capitalize on the two countries’ common Buddhist heritage, China has cultivated the majority Buddhist religious constituency, establishing the Sri Lanka-China Buddhist Friendship Association in 2015 and funding a Buddhist television station.115

China invites Sri Lankan journalists, academics, and policy professionals to the country, and it coordinates with them through platforms such as the Sri Lanka-China Journalists’ Forum.116 Academic institutes and think tanks affiliated with the CCP have ties with research institutes considered close to the Rajapaksas.117 One local stakeholder pointed out the persistence in extending invitations to visit China, “overwhelming” Sri Lankans to the point where they would agree to attend.118

These efforts have successfully created a reservoir of goodwill among the public, which looks at the United States and India through a more cynical lens.119 Some stakeholders said that the current impression in Sri Lanka is that pandemic-related assistance from the United States is conditioned on reducing the scope and intensity of ties to China—which makes the option of accessing U.S. vaccines less attractive on policy and strategic grounds, whatever its appeal may be on public-health grounds.120 The skepticism extends beyond responses to the pandemic, making Sri Lanka wary of motives behind any kind of aid from the United States. Meanwhile, Beijing has taken advantage of this vacuum in the relationship by identifying Colombo’s other immediate needs and extending a $500-million loan to ease the strain on the country’s foreign reserves in March 2020, followed by another $500 million in April 2021.121 The two countries also signed a $1.5 billion currency swap deal this year.122 China has also plowed ahead with vaccine and medical assistance: after providing testing kits and medical equipment in 2020, it has supplied 1.1 million doses of the Sinopharm vaccine to the country.123

UNPACKING VULNERABILITIES IN SOUTH ASIA

Part of the challenge facing South Asian states is that the rapid inflow of Chinese money and the exponential increase in Chinese influence over the last two decades has come against the backdrop of three pronounced systemic vulnerabilities: brittle state institutions, weak civil societies, and high potential for elite capture and corruption.

Not all of the four countries studied have all these vulnerabilities: some have stronger states; some have stronger civil societies; some have less “capturable” elites. Nor are they vulnerable in precisely the same way. But all display at least one of these vulnerabilities, which makes it harder for them to manage and mitigate the negative effects of a rapid inflow of external money and influence while giving them fewer levers with which to steer Chinese energies in directions that support their own national strategies, priorities, and developmental objectives.

Factors that determine whether and how each of these four states is vulnerable range from relative domestic capacity to how political systems and more or less independent civil society groups have evolved in recent history. The presence of a vulnerability does not necessarily indicate an absence of institutions or some independence of civil society. It merely suggests that the ability of these institutions and civic groups to shape and steer Chinese energies varies widely across the four countries.

This is why, for example, the issue of captured or capturable elites is more relevant in Sri Lanka than in Bangladesh, while civil society in Nepal is more capable of fulfilling its role in steering Chinese influence than is the case in Bangladesh. In Maldives, while the risks of elite capture substantially lessened with the change of government in 2018, this could change if power again changes hands in 2023 or 2024. Still, no matter who is in power, the structure of elite politics and the political economy in Maldives makes all of its elites less prone to external capture than those in Sri Lanka. As China’s role in the region will continue to grow—sometimes for good, sometimes for ill—it is important that South Asian stakeholders attempt to buttress their systems and to plug vulnerabilities by learning from the experiences of each other.

VULNERABILITY 1: FRAGILITY OF STATE INSTITUTIONS

Examples of brittle or weak state institutions include those that are too weak to conduct robust due diligence and proper investment screening; weak regulatory bodies; institutions with uneven law-enforcement capabilities, or poor anti-corruption systems; and judicial agencies that are too weak or captured to conduct proper judicial review of executive or legislative decisions.

Bangladesh, Maldives, and Nepal have vulnerable state institutions while Sri Lanka has stronger ones. Sri Lanka has the most robust administrative regimes and capable institutions among the focus countries, and Bangladesh, despite substantial indications of fragility in its institutions, follows closely behind. Yet both still face hindrances in the way they operate that make it harder to stave off external pressure, including from Chinese actors. Nepal is at risk because of long-standing institutional weaknesses that flow from its choppy process of post-monarchy democratization. Maldives suffers from inadequate institutional capacity.

Political pressure on institutions of democracy and governance

Fragility within the political system can manifest itself especially where the ruling political party has a strong leader or a large majority in the national legislature, allowing it to push through laws that benefit a narrow elite or to put unofficial political pressure onto other institutions. Such fragility results in corruption, inefficiencies in bureaucratic and law-enforcement mechanisms, as well as a failure to ensure transparency and adherence to procedure.

Bangladesh has a highly personalized political system in which power has rotated between two families. In a recent event to celebrate Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, Bangladesh’s “Father of the Nation,” Sheikh Hasina, his daughter and the prime minister, asserted that democracy needs an effective opposition to flourish.124 However this is hardly the case in Bangladesh where the Awami League–led government is currently in its third consecutive term, the opposition is in disarray, and the most important opposition leader has been convicted of graft.125 The economy has been unscathed from the effects of the pandemic, at least for now, and the country has recently flaunted its economic muscle by becoming the only country in the region apart from India to help a neighbor by extending it a loan.126

This has meant regime stability in Bangladesh, yet whether elections are free and fair has been questioned, forcing the prime minister to defend the process and making the country vulnerable to interference from a powerful outside power.127 The same allegations are likely to surface during the next elections in 2023.128

Unlike in Bangladesh, recent elections in Nepal, Maldives, and Sri Lanka have seen peaceful transfers of power—from Abdulla Yameen to Ibrahim Mohamed Solih in Maldives in 2018, from Sher Bahadur Deuba to K.P. Sharma Oli in Nepal in 2018 and then back to Deuba again in 2021, and from Maithripala Sirisena to Gotabaya Rajapaksa in Sri Lanka in 2019. This suggests a certain level of stability in democratic governance. But these states are still vulnerable to outside pressure because their governments have made or attempted constitutional amendments to their own benefit and to fend off political challenges.

This is most conspicuous in Sri Lanka, where China has been extremely active and where the Rajapaksa family has been engaged in a long-drawn battle to make the presidency, which it has controlled for extended periods, extraordinarily powerful.129 These efforts began with the eighteenth amendment to the constitution introduced by Mahinda Rajapaksa in 2010. This removed the two-term limit for the presidency and constitutional oversight on presidential appointments to independent commissions, replacing a constitutional council for such appointments with a parliamentary council that would be under greater executive control. The amendment was subsequently repealed under then president Maithripala Sirisena in 2015. However, this repeal has now been overturned by the current Rajapaksa government through the twentieth amendment, which returns many of the sweeping powers from the repealed eighteenth amendment right back to the president while making these actions unchallengeable, even on the basis of fundamental-rights applications. This raises concerns about the maturity of the constitution and the extraordinary reach it offers to the Rajapaksa family.130

Constitutional provisions have been similarly questioned in Maldives and Nepal. In Maldives, which democratized under the current constitution in 2007, powerful leaders in the ruling Maldivian Democratic Party have asked that provisions be changed to transition the country from a presidential to a parliamentary system. President Solih, however, is believed to feel differently.131 In Nepal, the new constitution, which came into effect in 2015 after two post-monarchy national constituent assemblies and years of political negotiations, has been at the center of protests and demands of amendments by Madhesis—people of Indian ancestry residing in the southern Terai region—and other marginalized communities.132 To complicate matters, the CPN-UML, which was in power since 2018, split into two factions, led respectively by K.P. Oli and Pushpa Kamal Dahal. Until he was deposed in July 2021, Oli had continued to serve as prime minister even after losing a vote of confidence in parliament as opposition parties failed to corral the numbers for a coalition government.133

Bureaucratic skill and corruption

The potential to compromise electoral and especially constitutional processes are not the only vulnerabilities in this category. For instance, even though Sri Lanka and Bangladesh fare well with developed institutions, questionable practices and pressure can make their bureaucracies ineffective. In Sri Lanka, for example, questionable actions by the Rajapaksa government began coming to light after the Sirisena government that took power in 2015 reviewed earlier decisions. This included investigations into allegations of nontransparent decisionmaking and corruption in China-funded projects.134 Officials were found to have ignored procedures to provide an unfair advantage to foreigners, including Chinese tourists, leading to losses for the exchequer.135 The Sirisena government also initiated an audit of China-funded projects carried out by its predecessor—including the Hambantota Port, the Hambantota Oil Tank complex, the Sooriyawewa Cricket Stadium, and the Mattala Rajapaksa International Airport (MRIA)—to check for their commercial viability or whether they were sweetheart deals for individuals and/or interest groups.136 This is a key example of how systemic vulnerabilities in the state can make it harder to resist debilitating forms of Chinese influence, much less steer Chinese energies in positive directions for a country.

There have also been allegations in Sri Lanka of mismanagement in different government departments leading to heavy losses. Stakeholders believe there have been instances of collusion between politicians and government departments, leading to cost escalation and mismanagement of funds. Some hint that Chinese projects moved forward because contractors were willing to bribe officials.137 The most serious of these allegations involve CHEC, the company in charge of constructing the Colombo Port City, which was accused of paying over $1 million for Mahinda Rajapaksa’s election campaign through various proxies.138 However, allegations of corruption raised against various members of the Rajapaksa family failed to make much headway in the Sirisena years and were eventually forgotten. In some cases, as with Gotabaya Rajapaksa, returning to power was followed by immunity against corruption charges.139

The political pressure led government departments to hide their lapses by making their operations more opaque, including by not releasing audited financial reports, which in turn made them less efficient.140 Environmental concerns, considered critical for an island nation like Sri Lanka, were disregarded—so while review agencies may be robust in terms of staffing or budgets, they failed to perform their duties in a way that could command public respect and credibility. The 2011 environmental impact assessment report for the Colombo Port City failed to acknowledge the possibility of coastal erosion and damage to the fishing industry. Nor was there any clarity on what the land reclaimed for the project would be used for.141 In fact, in the original agreement for the project, Sri Lanka was responsible for compensating China for damages in the event of a future natural disaster, not the other way around.142 In the case of the Southern, Outer Circular, and Colombo-Katunayake expressways, concerns about flooding were raised but ignored.143

In Maldives, the transfer of power brought to light allegations of domestic corruption by the prior government. In his negotiations with China to restructure debt, Finance Minister Ibrahim Ameer accused the previous government of accepting kickbacks from contractors to keep contract prices high.144 Solih said that “state coffers have lost several billions of rufiyaa . . . due to embezzlement and corruption conducted at different levels of the government.”145 This is reflected in the flagship China-Maldives Friendship Bridge, which has faced multiple questions about environmental degradation and threats to marine life.146 Even after the bridge was completed, Chinese subcontractors were found to be illegally mining sand, claiming that this was permitted under the construction agreement, which suggests that state weakness made the government unable to exercise its proper oversight, regulatory, and enforcement functions—a clear example of how state vulnerability enables unproductive forms of Chinese engagement.147 Another highly publicized deal, the Maldives-China Free Trade Agreement (FTA) signed during the Yameen years, has fallen by the wayside as the new government believes that its terms are not beneficial.148 Beijing’s lack of governance-related requirements and the low importance given to monitoring, along with limited capacity in the Maldivian state, seems to have helped corrupt practices go unnoticed.149

More broadly, a lack of institutional capacity and skills within the civil service enabled Chinese loans in Maldives that would have been screened differently by a stronger state with more robust institutions. Stakeholders argued that Chinese financial institutions differed from all other lending agencies not just in the speed with which they disbursed loans but also in their offers to take care of the “complicated backend” of financial agreements. This resulted in an unusual arrangement during the Yameen years in which Chinese institutions offered loans to Maldivian individuals or companies backed by a sovereign guarantee from the Maldivian state. On coming to power, the Solih government admitted that it did not know the total amount of such loans.150 The central bank stated $900 million as a probable amount of the sovereign guarantee, $300 million more than what the government itself directly owed China, suggesting state collusion with a well-connected private individual working with the Chinese partners.151 In 2020, the Export-Import Bank of China (China Eximbank) asked the government to repay part of a $125 million loan after a private debtor, Ahmed Siyam, failed to make a payment. Siyam—Yameen’s close political ally and a member of the legislature during his presidency—reportedly repaid the loan eventually.152 This kind of arrangement would be almost impossible in a strong state with robust diligence and monitoring mechanisms.

State institutions in Bangladesh are relatively robust compared to those in the other three countries, but stakeholders flag issues with corruption and political influence in approving Chinese-backed projects. By some accounts, almost a third of such projects are likely to be commercially and/or financially unviable but have been allowed because state institutions were unable to resist pressure from politically connected individuals who stood to benefit.153

In 2012, the World Bank pulled out of the Padma Multipurpose Bridge Project because requests to investigate corruption in the project went unheeded by state institutions.154 The project, currently funded by the government and China Eximbank, is considered one of the flagship projects showcasing the Bangladesh-China relationship. There have been no systematic reviews or answers on the charges. The Chinese SOE Sinohydro Corporation winning a $680 million contract in 2014 for part of the project also shows how brittle state institutions can become a problem. It won the bid even though it had been temporarily debarred by the World Bank.155 The companies that lost out said that they had informed the government about the ban on Sinohydro, which the authorities denied. Local newspapers reported that a former communications minister was working with the Chinese firm and had lobbied for it to win the contract. This was not the first time Sinohydro had run into controversy around an infrastructure project in Bangladesh—it had earlier worked on the Dhaka-Chittagong Highway Expansion project and was blamed for stalling it for two years.156 In a similar case, CHEC was given a contract at the Mirsarai Economic Zone in 2019 after joining a local consortium.157 The Bangladesh government blacklisted it just a year earlier, which technically prevented it from working on new projects, after it emerged that it tried to bribe officials.158

A more effective process of bureaucratic oversight, investment screening, and contract review could have raised questions at an earlier stage of these projects, at least pushing the Chinese and Bangladeshi partners to be more transparent and adhere to stronger rules of procedure. The problem has been present across all the four countries, with stakeholders reporting that Chinese loans seem to come with an unspoken expectation that there would either be no tender process or that the tender would be arranged to favor a Chinese contractor. A 2015 report by the Finance Ministry flagged this issue, pointing out that the practice went against the country’s formal transparency and contracting laws. A stronger state might have enforced these. The commerce minister even acknowledged the practice of going with China’s preferred contractors while talking about prospects of Chinese investment in SEZs.159

In Maldives, former president Mohamed Nasheed has raised a similar concern, adding that awarding projects to other countries should have been a more transparent process—“the tendering process happens here, the award (of contract) happens here, the monitoring happens here, and the labour can come from here.”160 To enforce “buy and hire Maldivian” policies would require a much stronger set of institutions than the country has had up to this point. Indeed, under the previous government, laws were amended to bypass competitive bidding.161 And in 2015, the constitution was amended in a rushed session of the legislature to allow foreign ownership of land, which is believed to benefit Chinese projects.162