Jeremy Cliffe

It was the biggest misconception of the post-1989 era: as it became richer, China would become more liberal and a “responsible stakeholder” in a US-led global order. As the country has become richer but more authoritarian, especially since Xi Jinping came to power in 2012, that stock theory has been replaced with a very different one: that China has detached prosperity from liberalism and that its upwards trajectory as a state-capitalist autocracy is all but certain.

This new assumption is so inherent to our understanding of the world that we rarely question it. I am guilty of this, often dropping the term “China’s rise” into my own writing about world affairs without troubling to justify or explain it.

The habit is near-ubiquitous. In the White House under Joe Biden, almost every big decision is viewed through the prism of an ever-mightier China that, the president has said, threatens to “eat our lunch”. When Biden joined forces with Boris Johnson and the Australian prime minister Scott Morrison to announce the “Aukus” submarines deal on 15 September, the three did not mention China, but they did not need to; the imperative to unite to contain the rising superpower before it becomes uncontainable was implicit. Other governments seek more of a middle way between the US and China, but one still predicated on the expectation that the latter will end up at least as powerful as the former.

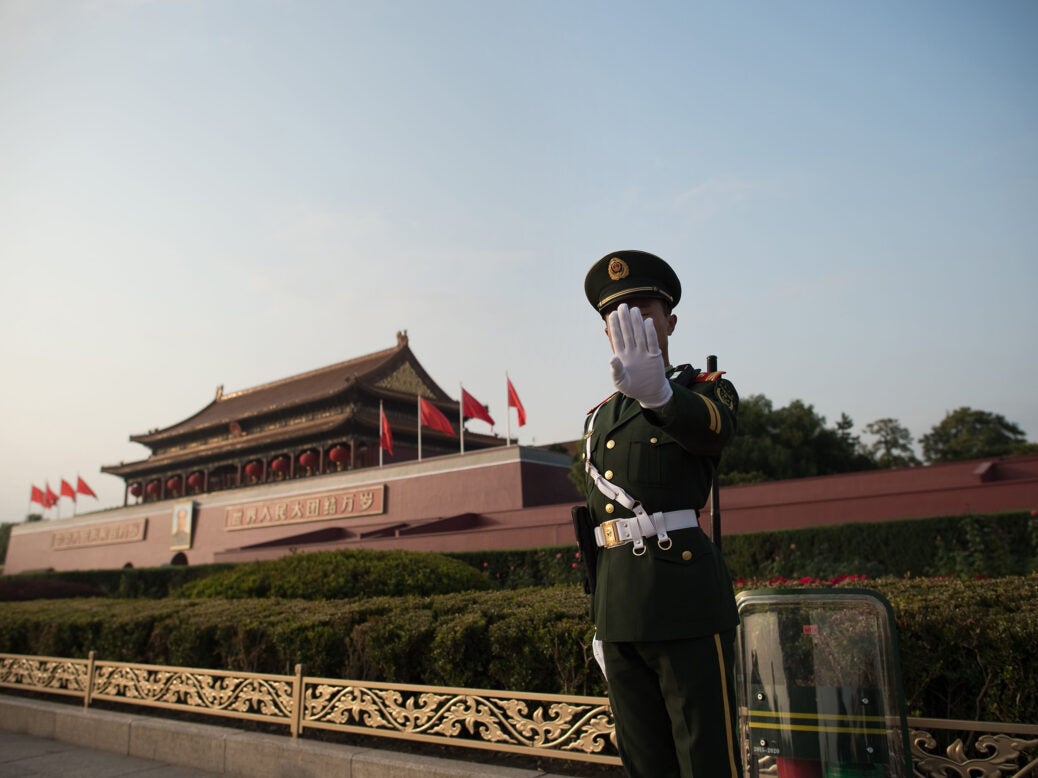

Beijing obligingly furnishes this expectation with awe-inspiring detail, from the staggering proportions of its economy (its property market is valued at $52trn) and the glittering, vertiginous skylines of its cities, to the cowing of Hong Kong, and the bombast with which the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) marked its 100th birthday in July – at which Xi warned the country’s enemies would “find their heads broken and bashed bloody against the great wall of steel forged by the blood and flesh of 1.4 billion Chinese people”. How could you not be daunted by such fierce vigour?

Yet when so many decisions by the West especially – economic, military, diplomatic – rest on that premise, it is worth asking what it would mean if the assumptions about China’s inexorable rise are disproved over the coming decades.

The months since the regime’s strutting display in July give ample reason to stress-test the idea. China is entering a politically sensitive time: the run-up to the CCP’s congress in November 2022, at which Xi will seek another five years at the helm, making him China’s longest-serving leader since Mao. The party wants to resolve some of the negative effects of the country’s sustained growth: reining in inequalities and corporate excess under the slogan “common prosperity”; squeezing the powerful tech firms that serve the retail and social-networking appetites of a burgeoning middle class; cleaning up a coal-heavy economy; and managing the demographic fallout produced by the combination of increased prosperity and a one-child policy relaxed only in 2013. On all of those fronts it is facing difficulties.

Today, China’s Evergrande – the world’s most indebted property developer with $300bn of liabilities – is on the verge of a default as Beijing tightens rules on leverage and the country’s long real estate boom tilts towards bust. As the China expert George Magnus wrote on newstatesman.com, the firm’s unravelling could send a shock through the financial system of a country that has “never experienced a meaningful decline in property prices”. The crackdown on technology giants such as Alibaba and Tencent, also part of Xi’s war on excess, has wiped more than $1trn combined off tech firms’ stock prices and spooked investors. China’s marriage of market economics and political Leninism appears to be faltering.

Rolling power cuts in recent weeks have prompted coal production to be ramped up, demonstrating the awesome scale of the challenge of decarbonising the Chinese economy. Combined with new outbreaks of the Delta Covid variant leading to local lockdowns, the energy crisis is slowing the economy. Manufacturing activity contracted in September.

Then there is that other long-term threat to Chinese prosperity: its rapidly ageing population. A census published in May showed China’s birth rate had dropped to 1.3 children per woman (compared with 1.6 in the US), while a new study by medical journal the Lancet projects that China’s population will halve by 2100.

These challenges all suggest that China has not managed to reconcile prosperity and authoritarianism as smoothly as the bullish accounts of its ascent suggest. Unfashionably bearish books that have warned about China’s future – Magnus’s Red Flags and Carl Minzer’s End of an Era – are now looking strikingly prescient.

What, then, if China’s problems turn out to be more than minor setbacks? This would demand the rethinking of many other assumptions too. Western corporate leaders and finance ministers reliant on Chinese growth would need to find a way to survive without it. Western strategists expecting a new Asian superpower would have to contemplate the prospect of a stagnating one. A Western order seemingly threatened by Chinese aggression and overconfidence might find that Chinese insecurity and instability pose the greater risk. Certainly, these are only possibilities. But possibilities surely momentous enough to warrant the question: “What if?”

No comments:

Post a Comment