Le Hong Hiep

During U.S. Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin’s visit to Vietnam in late July, the two countries signed a memorandum of understanding under which America will assist Vietnam to locate, identify, and recover the remains of Vietnamese soldiers who were killed during the Vietnam War but are still listed as missing in action (MIA). The move shows that 46 years after the war ended, Washington is still working hard with Hanoi to promote reconciliation between the two former enemies. Such relentless efforts have been part and parcel of America’s Vietnam policy since the two countries normalized relations in 1995.

This long journey toward reconciliation is vividly recounted in “Nothing Is Impossible: America’s Reconciliation with Vietnam,” a new book by Ted Osius, who served as U.S. Ambassador to Vietnam from 2014 to 2017. Inspired by a statement of Pete Peterson, the first U.S. ambassador to postwar Vietnam, that “nothing is impossible in United States-Vietnam relations,” the book provides the most detailed and insightful account so far of developments in U.S.- Vietnam relations since normalization, as well as the many challenges that the two countries have overcome along the way.

Osius is well positioned to write the book. He served twice at the U.S. diplomatic mission in Hanoi, first as a political officer shortly after normalization, and then as U.S. ambassador to Vietnam almost 20 years later. Osius’ extended engagement with Vietnam, which he summarized as “pursuing diplomacy with Vietnam for twenty-three years – under four presidents and seven secretaries of state,” enabled him to gain a deep understanding of the different contours of bilateral relations. This, in turn, provided him with the necessary ingredients to fill his book with fascinating accounts of how Washington and Hanoi have worked together to promote reconciliation and strengthen their ties.

The book traces the development of bilateral ties since 1995 through a series of “tangible stories of some prominent individuals as well as ordinary citizens,” underlying the fact that the reconciliation between the two countries has been a joint enterprise involving multiple stakeholders on both sides. While prominent figures, such as the late Senator John McCain, former Secretary of State John Kerry, and successive Vietnamese and U.S. ambassadors, have played key roles, other people, like the different government officials in the two countries’ foreign policy and defense establishments who worked silently behind the scenes, and even the lay people in Vietnam, have also played a part in the process.

For example, the hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese people who lined the streets to welcome President Bill Clinton in 2000 and President Barack Obama in 2016 during their visits to Vietnam show the Vietnamese people’s forward-looking view about America and their willingness to move beyond the tragic past between the two countries. In another case, Osius tells a moving story about his encounter with a Vietnamese woman on a bridge near the demilitarized zone that once divided north and south Vietnam. The woman said that Americans had destroyed the bridge many times and killed people she knew. But then, “in the intimate language used for family members,” she told the author that America and Vietnam are now friends, and that “today, you and I are younger brother and older sister.” During his confirmation hearing before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in 2014, Osius repeated the story as evidence of the Vietnamese “spirit of forgiveness and reconciliation.”

The reconciliation between America and Vietnam, as recounted by Osius, has happened through different measures and in different forms, ranging from efforts to heal wartime wounds to moves aimed at building mutual trust and respect. The book’s detailed and interesting accounts of these efforts help readers better understand the intricate inner workings of policymaking on both sides, and how they overcame various obstacles to reach compromises that keep bilateral ties moving forward. Some relevant and interesting examples mentioned in the book are lobbying efforts to get American authorities to approve the budgets for removing unexploded ordnance and cleaning up dioxin in Vietnam, to get Vietnamese leaders’ agreement for a cemetery of South Vietnamese soldiers in Bien Hoa to be properly maintained, or to persuade President Obama to host General Secretary Nguyen Phu Trong at the Oval Office, despite Trong’s status as communist party chief, during his historic visit to the U.S. in 2015.

Although the book’s key theme is U.S.-Vietnam reconciliation, it also covers different future-oriented developments in bilateral ties, such as economic, education, and defense cooperation initiatives. The signing of the U.S.-Vietnam Bilateral Trade Agreement in 2000, the establishment of the Fulbright University Vietnam in 2016, and the visit of U.S. aircraft carrier USS Carl Vinson to Vietnam in 2018, all described in detail in the book, are relevant examples of two countries’ commitment to promoting their common goals and responding to future challenges, be it in each country’s pursuit of wealth and development, or over the testy waters of the South China Sea.

The book generally presents an optimistic view about U.S.-Vietnam relations, but the author also adds nuance to this narrative by discussing the challenges that constrain them. Two particular issues are examined at length in the book: the objection of certain segments of the Vietnamese refugee communities in America to Washington’s efforts to build ties with Hanoi, and the two countries’ differences over human rights issues.

The latter case is clearly illustrated by the author’s account of tense negotiations with Vietnamese officials on arrangements for President Obama to meet with members of civil society during his visit to Vietnam in May 2016. Osius secured the agreement from a Vietnamese leader that Vietnamese authorities would not interfere in the meeting as long as they were given a list of participants in advance, and that the participants had never been investigated by Vietnamese authorities before. However, to American officials’ frustration, on the eve of the meeting, Vietnamese security officials used different tactics to detain or intimidate five of the nine invited participants, which almost caused the meeting to fall through.

Despite America’s repeated commitments to respect Vietnam’s political system, some Vietnamese leaders remain paranoid about the vague threat of regime change supposedly caused by America’s “peaceful evolution” scheme. But such fear is misplaced. As Osius’s book shows, America has learned to respect Vietnam’s political interests, and has a strong desire in strengthening ties with Vietnam, especially against the backdrop of its intensifying strategic competition with China. Contrary to these officials’ belief, a stronger relationship with the U.S. will help strengthen, rather than undermine, the regime of the Vietnamese Communist Party. Numerous historical examples, from Chile, Nicaragua, and Cuba to Iran, Iraq, and North Korea, have shown that regimes friendly to the U.S. and its interests will fare much better than hostile ones.

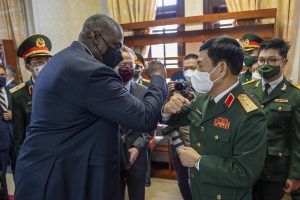

However, officials who maintain such an outdated thinking seem to be in the minority. As shown by recent developments, including visits to Vietnam by Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin in July and Vice President Kamala Harris in August, as well as the U.S. visit by Vietnamese President Nguyen Xuan Phuc this week, U.S.-Vietnam relations still maintain the strong momentum once witnessed by Ambassador Osius during his posting in Hanoi. The two countries are still working hard to move beyond reconciliation towards more substantive cooperation, and to keep alive Pete Peterson’s observation that “Nothing is impossible in United States-Vietnam relations.”

No comments:

Post a Comment