Dino Krause & Mona Kanwal Sheikh

9/11 and the US-led invasion of Afghanistan that followed have been defining events for the development of global jihadism during the past twenty years. With the return of the Taliban to power in Afghanistan, al-Qaeda and IS are back in the international spotlight. The latter organisations have managed to regroup, reorganise and strike back over the years: how will the Taliban takeover affect their future, both in Afghanistan and abroad? And what can research tell us about the development of al-Qaeda and IS over the past two decades?

On 11 September 2001, a group of jihadists affiliated with al-Qaeda, at the time led by Osama bin Laden, hijacked and crashed four commercial airplanes, two of which were steered into the twin towers of the World Trade Center in New York City, causing thousands of civilian victims. The events were crucial in defining the further development of global jihadism in various ways, starting with the US-led invasion of Afghanistan later that year, the temporary expulsion of the al-Qaeda network from its former safe haven, and its subsequent creation of affiliate branches in countries such as Algeria and Yemen. In 2014, al-Qaeda’s Iraqi branch formerly split from the organisation and transformed itself into a transnational actor in its own right, the so-called Islamic State (IS). The group then declared a caliphate and established its rule over a territory spanning wide parts of northern Iraq and Syria, until by March 2019 an international coalition comprising Kurdish-led units and pro-Iranian Shia militias, as well as heavy US air support, managed to oust IS from all population centres in its core territory. Most recently, the Taliban’s return to power in Afghanistan has placed al-Qaeda and IS, both of which remain active in the country, back in the international spotlight.

Twenty years after 9/11, two and a half years after IS’s ‘caliphate’ was brought to an end and with the Taliban in power in Afghanistan, what are the current statuses of IS and its major transnational rival, al-Qaeda? How influential are these organisations, and in what parts of the world are they active? What explains their resilience in the face of heavy-handed counterterrorism campaigns?

Al-Qaeda and IS today

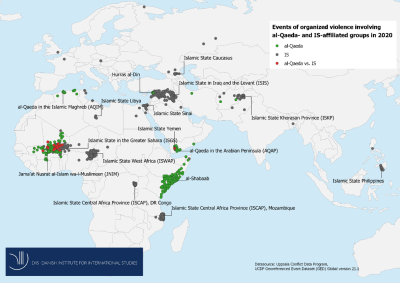

Globally, during 2020 al-Qaeda and IS were engaged in organised violence, that is, fighting against governments or other non-state groups and attacking civilians, in no less than 28 countries. While some of these countries experienced only a few terrorist attacks claimed by IS, such as Austria or France, or low-scale insurgencies, such as Russia’s North Caucasus region, the two organisations’ affiliate groups enjoyed a highly consolidated presence in several other states. Despite its loss of territorial control in Iraq and Syria, IS has not disappeared from either of these countries. In fact, the group’s scale of operations increased markedly from 2019 to 2020. In Syria, the number of fatalities from events involving IS more than doubled, and in Iraq it increased by over 30%.

Outside Iraq and Syria, there are four hotspots of jihadist violence on the African continent. In Mali and Burkina Faso, al-Qaeda-affiliated jihadists, who had already been involved in temporarily establishing the so-called ‘Islamic Emirate of Azawad’ in 2012, clash regularly with their rivals from IS’s Greater Saharan branch (ISGS). A few thousand kilometres further east, Islamic State’s West Africa Province (ISWAP), formerly Boko Haram, has extended its reach from northern Nigeria into Cameroon, Chad and Niger. On the other side of the continent, in Somalia, the al-Qaeda-affiliated al-Shabaab continues to benefit from the lack of the state’s presence through wide swathes of the country. Meanwhile in Mozambique, an initially small, local jihadist movement, Ansar al-Sunnah, has declared its allegiance to IS and is now fighting under the banner of the Islamic State Central Africa Province (ISCAP). Although geographically contained in the northeastern Cabo Delgado province, with some spillover already having taken place on to the Tanzanian side of the border, the intensity of its attacks against both civilians and government targets has increased dramatically. In 2020 Mozambique ranked third behind Nigeria and Somalia among the world’s states most affected by al-Qaeda and IS-related violence.

If we look at attacks in the West (i.e. North America and Europe) since 2014, almost all of them were claimed by IS rather than al-Qaeda. There was a clear overlap between the era of IS’s self-declared caliphate (2014-2019) and the frequency and intensity of these attacks: between 2015 and 2017 alone, according to data from the Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP), IS-related attacks caused 307 fatalities in the West, almost a third of which resulted from the November 2015 attacks in Paris. However, when IS began to lose territory in Iraq and Syria, its ability to mobilize and instruct fighters in the West greatly decreased, as reflected in a fall in the number of fatalities to 24 for the entire three years from 2018-2020. Meanwhile, al-Qaeda claimed responsibility for only two single attacks in the West throughout this entire seven-year period, namely the 2015 Charlie Hebdo attack and the shooting at a US Naval Air Station in Pensacola (2019).

The role of military interventions

Throughout the past twenty years, the dominant strategy pursued in addressing the jihadist threat has been a military one. Of the 25 states located in Africa, the Middle East or Asia that experienced organised violence involving al-Qaeda- or IS-affiliated groups during 2020, eleven had received external military support through active troop provision during the previous ten years and/or were still receiving it. These campaigns against jihadists have sometimes led to tangible, short-term successes: given the military superiority of the intervening powers over the jihadists, the latter’s proto-states were often disbanded, and control over major population centres was re-established. This was the case in northern Mali during 2013, when the Emirate of Azawad was dissolved, and in Syria and Iraq, where, by March 2019, the Islamic State had been expelled from all the major cities it controlled. Even without direct military interventions, the US’s drone campaign has undermined jihadist groups through the targeted killing of prominent leaders.

Still, despite these military successes, sooner or later the jihadists were often able to regroup, reorganise their insurgency and strike back, sometimes at a higher rate than before. These developments illustrate that in the long run military interventions carry the risk of playing into the hands of the jihadists, especially where they cause high numbers of civilian casualties. Jihadists capitalise on the opportunity to present themselves as liberating forces fighting against foreign oppressors.

In recent years, we have seen a shift in who intervenes militarily, with Western states growing increasingly reluctant to engage in such military missions, as exemplified by US troop withdrawals from Afghanistan and Iraq, and the French announcement that it would end its ‘Barkhane’ mission in the Sahel by 2022. In turn, non-Western states such as Iran, Russia, Turkey or Saudi Arabia are taking a more active role. Most recently, Rwandan forces, backed by troops from the Southern African Development Community (SADC), have entered the fight against IS’s affiliate in Mozambique. It is important to note that jihadists have not only mobilized against Western states as foreign oppressors. For instance, in Somalia, public resistance to the Ethiopian military presence has fuelled local support for al-Shabaab. In Kashmir, jihadists have long mobilised against Indian rule, seeking unification of the disputed region with Pakistan. And when Turkey joined the US-led coalition against IS in 2014, this was followed by a series of IS-inspired and -coordinated attacks against Turkish targets, despite Turkey being a state consisting predominantly of Sunni Muslims.

Why are these groups so resilient?

Al-Qaeda and IS frame their insurgencies in similar, religious terms, drawing upon a narrative that is centred on insults to religion by both domestic and foreign actors. However, there are many pathways that can explain why civilians decide to support or join a jihadist movement. In some areas this might have to do with socioeconomic conditions, in others with social marginalisation or personal redemption, or accepting the jihadists’ discourse that portrays globalisation as a Western-led project at the expense of the world’s Muslims. The existing literature points towards political indignation over incumbent regimes that are perceived as unjust or repressive as another key factor.

As regards socioeconomic explanations, there are substantially different mechanisms at play, varying between regional contexts. In several of the Sahelian countries, jihadists have capitalised on the frustrations of rural populations suffering from a lack of public services, security and/or economic perspectives. In Bangladesh, in contrast to what one might expect in a developing country, one of largest terror plots was traced to an upper-class private university student with internet access to global jihadist propaganda. Hence, there are no simple explanations that apply to all regional contexts.

On the organisational level, a key factor that explains the success of al-Qaeda and IS has been the flexibility with which their regional branches operate. Because most of these branches (or their constituent factions) had existed as more or less coherent rebel groups prior to pledging allegiance to al-Qaeda or IS, they also had established networks to recruit fighters into their ranks. This means that their recruitment tactics are highly adjusted to local dynamics, with the importance of religion varying substantially between different regional contexts. In general, al-Qaeda and IS have appeared in conflict settings in which local grievances merge with the religious ‘solution’ they offer.

We know from previous research that rebel groups tend to be more resilient if they can seek refuge from the counterinsurgency campaigns of one state by escaping across the border into the territory of a neighbouring state. The reason for this is simply that the first state’s military is unable to operate freely on territory beyond its borders. Moreover, inter-state cooperation and mutual intelligence-sharing is often hindered by rival strategic interests among neighbouring states. Al-Qaeda and IS are able to reap the benefits of such operational flexibility because their struggles are transnational. They therefore do not depend on any country or territory, in contrast to rebel groups that have been formed with the explicit goal of toppling a government, achieving territorial independence or their ethnic group seceding. If we look at al-Qaeda, for instance, although it was deprived of its safe havens in Afghanistan and Pakistan after the US-led invasion in 2001, it was able to adapt to this loss by relying on and investing more heavily in its transnational network of affiliated organisations in countries such as Algeria, Iraq and Yemen.

When we take a closer look at the regional affiliates, some of these groups have also transformed themselves into transnational actors. For example, al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) was originally an Algerian jihadist rebel group, which was challenged by the counterterrorism campaign of the state and became almost insignificant in Algeria itself over the years. However, in parallel to its decline in Algeria, some of the group expanded into Algeria’s southern neighbour Mali, where they established links with local rebel movements. Today, the result of many such mergers is al-Qaeda’s new Sahelian affiliate, which is active not only in Mali, but also in Burkina Faso.

Political solutions

Recent research shows that it is harder to negotiate once a movement or a conflict has become transnational. Examples of real peace negotiations with al-Qaeda or IS-affiliated insurgent groups are extremely rare, despite occasional negotiations over temporary ceasefires, humanitarian access to conflict areas or prisoner releases. While the Afghan Taliban may, at first sight, appear as a counter-example, it is a movement whose struggle has always been focused on Afghanistan, and despite its protection of al-Qaeda, it has always remained a distinct, independent organisation. A nationally limited focus also characterises other examples of jihadist rebel groups that have signed peace agreements, such as the MILF rebels in the Philippines in 2014. Similar examples can be found in Tajikistan, where a peace agreement allowed for the political creation of the so-called Islamic Renaissance Party in 1997, or Somalia, where several Islamist factions signed the 2008 Djibouti agreement and merged into the Transitional Federal Government.

One of the challenges in negotiating with transnational jihadist groups is the far-ranging, maximalist claims that involve a rejection of nation-state boundaries, democratic politics, basic human rights for substantial parts of the non-male, non-Sunni Muslim parts of the population and to a large extent transnational aspirations: if a group strives for transnational expansion or the creation of a caliphate, why would it agree to demobilise and give up its struggle in return for political power or territorial autonomy in a particular state or region? The logic of conventional political negotiations does not seem to apply here.

Another difficulty stems from the audiences that both governments and transnational jihadists communicate to. Most al-Qaeda and Islamic State-affiliated groups are proscribed terrorist groups, and negotiating with them is highly unpopular for most governments affected by their violence. On the other hand, the jihadists also communicate to a transnational audience and are eager to prove themselves to be more pious fighters than other rebel groups or jihadist rivals. Thus, it is also difficult for these groups to communicate to their supporters that they want to negotiate with the same governments, which they routinely denounce as ‘apostates’ and ‘disbelievers’.

Recent developments indicate certain changes, at least when it comes to al-Qaeda-affiliated groups. For several years, al-Qaeda’s central leadership has been weakened due to the killing of many high-ranking members. This has dramatically limited the leadership’s ability to communicate and coordinate with regional affiliates that are increasingly acting autonomously. Last year, al-Qaeda’s Sahelian branch, JNIM, announced that it would be willing to enter peace negotiations if France would withdraw all its forces from the region. More recently, reports have emerged of a clandestine agreement reached between the Government of Burkina Faso and JNIM in the northern parts of the country. Another example is Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham, the Syrian jihadist group that broke ties with al-Qaeda in 2016 and has since sought to rebrand itself as a moderate, pragmatic Islamic group signalling its openness to dialogue and negotiation. It will be interesting to see what similar cases may emerge in the future, or whether these will remain exceptions. It is possible that, by weakening the links between al-Qaeda, IS and their regional affiliates, channels for negotiations might open, although we have no comparable examples of IS-affiliated groups as yet.

The Taliban in power: impacts for al-Qaeda and IS?

The Taliban leadership responsible for the Doha-based negotiations assured the US that it would not allow an al-Qaeda resurgence on its territory. There are major incentives for the Taliban not to renege on this promise. First, the new Taliban government will need international financial assistance. Since 2002, the EU has paid over four billion euros in development aid to Afghanistan – no other state has received more. Even if the Taliban regime seeks closer relations with non-Western powers –Russia, China, Iran or Pakistan – these countries also have a strategic interest in reducing the risk of terrorism against their own citizens and will thus push for the Taliban to contain al-Qaeda. Second, the Taliban do not depend on al-Qaeda’s support today, unlike in earlier years, when a more coherent and stronger al-Qaeda was able to provide them with millions of dollars every year. However, this was at a time when al-Qaeda itself had a robust fighting force of thousands of fighters, many of them foreigners, and had stable exchanges with allied groups across the world. This form of exchange has become much more difficult in recent years, as al-Qaeda’s own financial capabilities have become drastically reduced. Third, even though unlikely in the short run, a campaign of al-Qaeda-orchestrated attacks in the West could spark renewed military action to destabilize or topple the new Taliban regime, a scenario not in the latter’s strategic interest.

However, there are also reasons to be cautious and not to take the Taliban’s statements as revealing the full picture of their interactions with al-Qaeda. To begin with, in recent years Taliban leaders and politicians affiliated with the movement have spoken very positively of al-Qaeda on several occasions, publicly memorialising the death of Osama bin Laden and glorifying common fighting experiences against foreign powers. The fact that the Taliban and al-Qaeda have collaborated over several decades, even in the years following the 2001 US-led invasion, means that there still are bonds between the two groups. It is also worth considering that both al-Qaeda’s top leadership around Ayman al-Zawahiri and the leaders of regional affiliates continue to highlight their allegiance to the Taliban, despite the latter’s formal guarantee to the US that they will not allow al-Qaeda to use Afghanistan as a safe haven.

IS constitutes the third jihadist actor on the scene in Afghanistan. Already in recent years the group has clashed with the Taliban, losing scores of its fighters in these armed confrontations, including several of its top leaders. The events in Afghanistan mirror those from other battlefields, such as the Sahel, Yemen or Somalia, where local IS affiliates have been fighting against al-Qaeda-affiliated groups. Should the Taliban consolidate their grip on power in Afghanistan, the prospects for IS in the country appear grim. Only hours after the Taliban’s takeover of Kabul, images of a deceased former IS leader emerged, who was apparently killed by Taliban fighters during a prison raid.

Various case-based studies have suggested that, in order to undermine public support for transnational jihadist groups, one strategy could be to integrate Islamist actors into the political system. The relative openness of political systems towards Islamist parties has been cited to explain why, despite a persistent insurgency in the Philippines, al-Qaeda and IS have struggled to expand more extensively in South and Southeast Asia. This points to the potential effects of integrating Islamists into political systems as a bulwark against transnational jihadism. Although the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan may work to contain IS-related groups in the country, it can still inspire other jihadist movements. In the present case, there might be a regional spill-over effect, as the Pakistani Taliban were quick to renew their pledge of allegiance to the Afghan Taliban leadership. Thus far, the Pakistani Taliban have operated as a sister organisation to the Afghan Taliban, with both movements having adopted a nationally oriented focus. Whether the Taliban takeover could lead to increased transnational cooperation between the two movements remains to be seen. In any case, the greater the Afghan Taliban’s willingness to share power and to attract the support of foreign states, the less probable it appears that they would be willing to strengthen their formal bonds with their Pakistani affiliates across the border, as such a step would likely spark both domestic and transnational opposition.

No comments:

Post a Comment