The working group on the futures of climate-related conflict considers climate change a major environmental threat. It is also likely to have a seismic impact on human security, access to resources and (violent and non-violent) conflicts. Climate change will create new challenges and dramatically exacerbate existing ones, including through increased pressure on land use, a diminishing availability of drinking water and damage to coastal areas. These challenges will affect the distribution of key resources and communal living within as well as across the confines of national borders. As such, climate change has the potential to become both a risk multiplier and direct cause of conflict.

We identified four key trends that pervade both of our scenarios for the years 2035: 1) decreasing volumes of drinking water for large parts of the world; 2) the growing political and economic power of China; 3) increasing urbanization across high- and middle-income economies; and 4) (violent and non-violent) conflict, contestation and cooperation between states. The use of technology, including (broadly understood) geo-engineering technology and, in particular, local and regional weather modification technology, is relevant for both our scenarios. While we understand geo-engineering as “the deliberate, large-scale manipulation of the planetary environment to counteract anthropogenic climate change,” our analyses focus primarily on weather modification technology and some “nature-based” solutions at the local and regional levels.

Table 1: Key Uncertainties and Respective Projections for a Pleasant (Green) and Unpleasant (Red) Future of Climate-Related Conflict

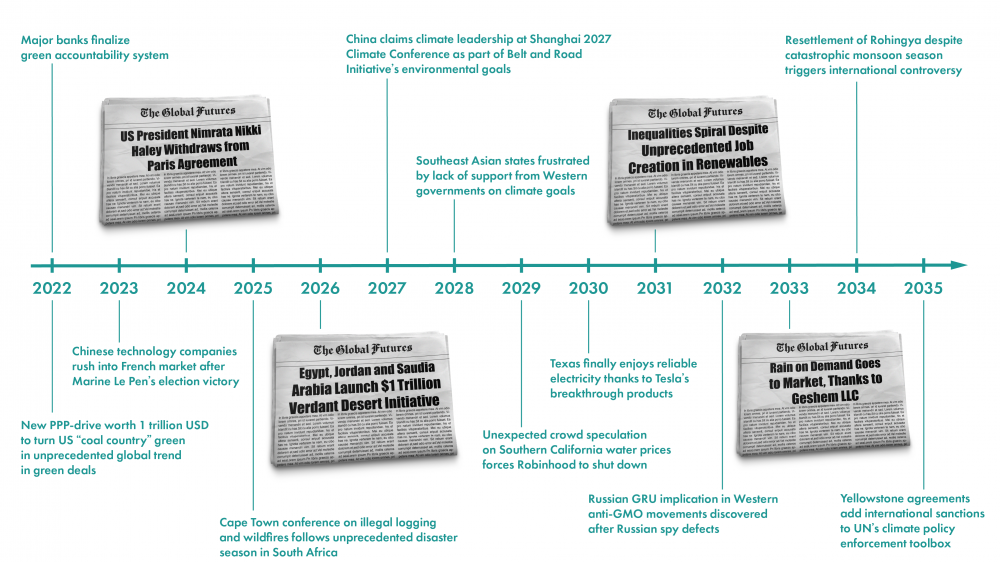

Scenario I (“Climate Disorder Under Orders”) examines how three primary dynamics will evolve into 2035. First, local politics will increasingly influence national and global politics. Second, technology will occupy a significant role in countering the negative impacts of climate change and, at the same time, pose new challenges and risks to conflict mitigation. Third, traditional alliances will fracture and wither, creating space for new forms of cooperation (including public-private partnerships) and alliances between countries to emerge. While these three dynamics occur simultaneously and influence one another, they are presented separately so as to emphasize each one’s key drivers. This scenario explores how the highly disruptive consequences of climate change could: affect the availability of natural resources; impact global financial markets; increase international investment in geo-engineering and, in particular, weather system technologies; reshape the contours of conflict between nation states; and lead to a reimagining of the future of climate-related migration.

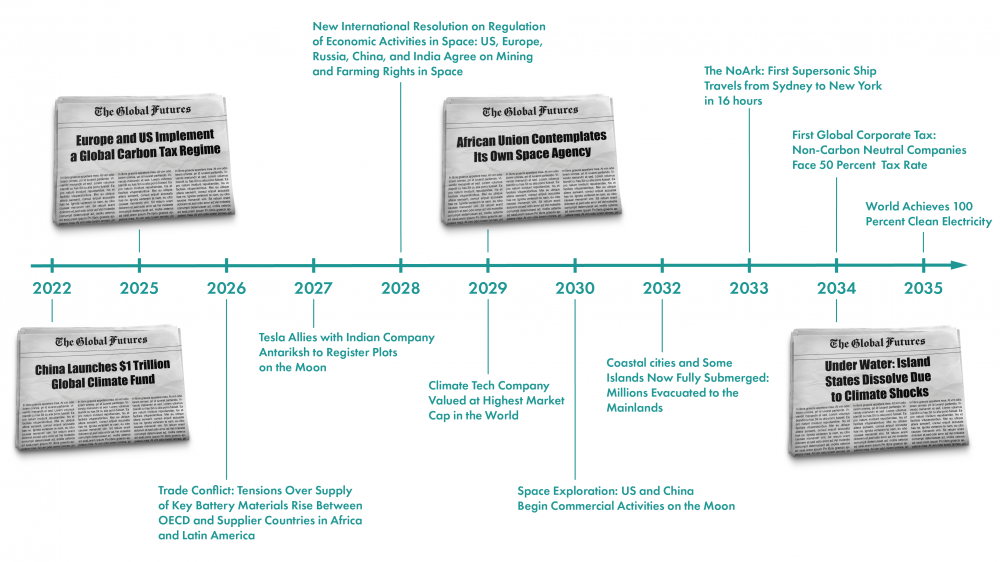

In Scenario II (“Building the Great Green Wall”), international cooperation results in more effective global governance on climate policy, which is the key driver within the multi-polar world emerging through 2035. This new global order is shaped by newly forming regional blocs, which permit access to scarce natural resources, capital, military power, and technologies. These blocs are led by regional superpowers (India, China, the EU, the US, etc.) that negotiate on behalf of their member states. Most conflicts between these competing blocs ignite around the issue of access to resources needed for machine-driven innovations for food production, the energy transition toward 100 percent renewable energy, and the green mobility transition. Consumption and production growth drive scarcity of critical resources, such as rare earth materials, fertile agricultural land and access to freshwater. International migration remains a contested issue. While climate-related migration is well managed nationally (as part of larger national climate adaptation frameworks), the international community continues to fail cross-border migrants fleeing war, violence and extreme poverty.

Snapshot of Scenario I

In 2035, all three dynamics that drive this scenario (local conflict, technological advancements and global political disjunction) are at play, with local and national politics acting as first among equals. Humanity is struggling with the effects of numerous intense climate events. So-called Climate Clubs – countries with the same climate objectives – are created to enhance collaboration on technologies and policies to address climate-related challenges. This results in regional polarization, with the US and China as the two main leaders in a multipolar world. While weather modification technology exists, only certain countries, citizens and corporations enjoy access to it, and the effectiveness of these technologies in mitigating the negative impacts of climate change is disputed.

Erratic climate events precipitate skyrocketing profits for futures pricing, thus benefiting investors and the upper echelon of societies.

New food technologies, such as 3-D printed foods, are available only to the very rich, while scalable technologies, such as genetically modified (GM) seeds, face serious push-back from farmers in emerging economies. The spread of mis- and disinformation regarding GM food technology (such as that these foods cause health issues and impotency) exacerbates resistance to GM technology, leading to food shortages in countries like India and Nigeria and destabilizing regional competitors. Erratic climate events precipitate skyrocketing profits for futures pricing, thus benefiting investors and the upper echelon of societies. Meanwhile, high volatility in global resource management (reflected, for instance, in the short cycles with which global extraction companies open and close their regional offices) exerts even more pressure on those already buckling at the bottom of different national economies.

Regional and global politics are also affected by these developments. Closer partnerships blossom between countries with similar climate objectives (e.g., between the US and Japan), while traditional alliances (such as between the US and the EU) wither. This creates new opportunities for collaboration and partnerships in other areas, such as collaboration between China and the EU in the realm of smart grids. Specialized or highly skilled workers are gravitating toward spaces where economic opportunity is high, thus forsaking areas subject to economic stagnation due to the adverse effects of increasingly frequent climate shocks.

What Are the Main Factors Driving this Scenario?

All Politics Are Local

For governments across the world, domestic and global political decision-making are influenced by developments in the US-China relationship and perceptions of China’s advancements in green technology. Governments feel pressured to choose between backing the US or the China ‘camp’. Domestic politics intersect with geopolitics, causing significant polarization around regional investments in, agreement with and distribution of effective technological as well as non-tech solutions to climate change. This generates economic and political pressures globally.

US-China relations: Because of US political vacillation and bi-partisan hostility toward China, Beijing alienates the US and sides with the increasingly fractured EU on climate policies as well as technological cooperation. Many Southeast Asian countries’ climate policies emulate China’s strategy, the result of Beijing’s successful COVID-19 vaccine diplomacy and lessening tensions in the South China Sea.

Privatization of common public goods: Privatization of common goods (such as water) will fuel inequities in access to natural resources.

Domestic climate-related migration: Highly specialized economic migrants leave areas that are subject to economic stagnation due to the adverse effects of increasingly frequent climate shocks. Major cities become areas of concentration for people with privilege and talent, leading to over-saturation. At the same time, around the world, areas vulnerable to climate change become increasingly abandoned and dilapidated.

No Deus Ex Machina

There is an overall push in the search for technological solutions to counter the negative impacts of climate change. This invites unprecedented investment in weather system intervention technologies (locally as well as regionally), which, in turn, spurs corporate espionage. Technology mitigates some climate shocks; however, it also intensifies challenges in the realm of conflict mitigation, as irregular and inconsistent access to technology breeds conflict internationally and locally.

Water scarcity: Water scarcity continues to threaten countries around the globe. As a result, technologies like seawater desalination and weather manipulation (through atmospheric water capture, precipitation and more) are deployed at a growing scale. Issues like waste dumping and resource grabbing intensify within and across world regions (especially in the Global South, where land property rights are weak).

AgTechs: The efficiency of agriculture improves, a development that is driven by innovative AgTechs (which include technologies like precision robotics and the use of space data for agriculture). However, global needs persist as the world’s population continues to expand. Moreover, growing resistance to GM seeds (a function of health concerns and misinformation) leads to global food shortages.

Fractures and New Connections in a Multi-Polar World

Traditional alliances fracture and wither, making space for new constellations of collaboration between countries and public-private sector partnerships in various jurisdictions. Some countries foster their alliances at the expense of regional polarization.

New partnerships: The fracturing of traditional alliances creates new pressures for innovation and business coordination.

Carbon tax and loans: Global financial markets begin to mandate carbon taxes, and relevant actors factor the costs of environmental and climate change impacts into their decision-making about loans.

Scenario I: Climate Disorder Under Orders

All Politics Are Local

By 2035, many parts of the world will have suffered from devastating climate disasters. In the past 15 years, the world has experienced a ten-fold increase in the number of typhoons, hurricanes, tornadoes, and wildfires. This has led to crop shortages, water insecurity and high infrastructure costs worldwide. This period has also seen soaring investments in technology, futures of natural resources and commercial space exploration (such as in the low Earth orbit by actors like Starlink or OneWeb). A global scrambling for access to natural resources and rare earth materials, along with a decade and a half of EU-China climate competition, has divided the world into vying blocs: one led by the US, one led by China and a third group of states fighting for their very survival. In an effort to take matters into its own hands, the US backs the Yellowstone Agreement, which comes into effect in 2035. This agreement establishes the North American Climate Goals, as the Paris Agreement flounders. The same year, several Southeast Asian countries join the Thimphu Agreement, thus setting new clean water goals to protect freshwater resources in a region already plagued by water shortages.

By 2035, the world has experienced a ten-fold increase in the number of typhoons, hurricanes, tornadoes, and wildfires. Credit: Tom Cooper (via Getty Images)

Continued climate shocks over the last 15 years have resulted in an increase in economic migration among specialized laborers: in the US, skilled workers move from Midwest and North-Central states to other regions in search for economic opportunities. Similar migration patterns transpire in coastal nations in the Global South. By 2034, those living in rural areas in the US average more than two-hour drives for a general practitioner visit. In the Global South, this average increases to four hours as many hospitals are abandoned due to scarcities in key supplies, such as water, hand sanitizers, face masks, and other essential equipment.

The increasing intensity and frequency of climate disasters have forced the US government and private sector actors to invest in the green economy. The US green economy is booming, with 250,000 jobs created month after month in 2031. Profits have continued to multiply for manufacturing companies and those at the top, with the S&P and Dow Jones industrial averages reaching record highs, particularly for prices of futures on natural resources. However, work force insecurity has also continued to increase. Greater automation, coupled with volatility in the markets (the largest ever recorded across specific commodities), has led to an unequal distribution of jobs. In economic terms, the fierce race to restore planetary health has not benefited everyone.

The year 2030 commenced with the US-China climate competition (and, in some areas, cooperation) drawing comparisons to the US-Soviet space race of the 20th century. The scientific journal Nature Climate Change speaks of the “21st Century Climate Recovery Race.” Worldwide, investments in weather modification technology, food security and digital health continue to perform well. In 2022, US venture capitalists’ 1 trillion USD investments in the so-called Fresh Start initiative to support the Green New Deal has demonstrated promising results. Meanwhile, some parts of the world – first and foremost, Southeast Asian countries – feel left behind by Western governments as the latter focus on their own populations and seem to abandon the principle that “we are all in this together” when it comes to climate change.

The increasing intensity and frequency of climate disasters have forced the US government and private-sector actors to invest in the green economy. Credit: Science in HD (via Unsplash)

In 2028, after years of suffering from devastating climate events with meager assistance from Western governments, a number of Southeast Asian states (Vietnam, Philippines, Indonesia, etc.) come together in a show of unity and jointly commit to a goal of reaching net zero carbon emissions by 2050.

Several climate catastrophes between 2024 and 2027 have shocked people around the world. Unseasonal winds and rainstorms across Europe have reached up to 200 km/h; the Marshall Islands and the Maldives have submerged; severe and prolonged droughts in the Middle East and other volatile regions like the Horn of Africa have fueled regional destabilization and conflict. By 2026, countries across the world are waking up to the undeniable reality that climate change is real and here to stay. Governments shift their resources to improve climate shock resilience, and worldwide investments in natural resources soar, resulting in unprecedented profits on futures like timber, which increases 150-fold.

By 2026, countries across the world are waking up to the undeniable reality that climate change is real and here to stay.

Concerns over the US’ faltering commitment to the Paris Agreement, coupled with ongoing climate disasters across the globe, have resulted in a scramble for critical natural resources and ensued in higher tariffs and protectionism during the last quarter of 2026. Related job losses have affected working classes worldwide. Sensing an opportunity, the Chinese government has stepped up, promising to lead global efforts in climate change mitigation and to prioritize environmental friendliness (and jobs creation) as part of its Belt and Road Initiative at the 2027 Shanghai Conference. In response, US state governors and tech leaders have vowed to continue the Green New Deal, which benefits both Americans and fellow world citizens.

Several climate catastrophes between 2024 and 2027 have shocked people around the world and further fueld destablization and conflict. Credit: zakir hossain chowdhury / Barcroft Media (via Getty Images)

The 2024 US elections see US Ambassador and Republican candidate Nimrata Nikki Haley elected as US president. Fearing that the climate critics would undermine the Fresh Start initiative and the progress made on the Green New Deal, Democrats redoubled their efforts to secure the House of Representatives but ended up losing the Senate. Over the next four years, Republicans and Donald Trump supporters relentlessly attack the Paris Agreement. The possibility of a US exit from the agreement and the influence of Donald Trump continue to cast a shadow over domestic and international politics.

In 2022, motivated by considerations of their social relevance, legacy, family, and philanthropy, venture capitalists have invested heavily in green and renewable energy. Encouraged by the Biden administration’s efforts to lead the fight against climate-related security challenges, venture capitalists and groups in the US and around the world (for example, Tim Draper, Guggenheim Partners and others) have invested almost 1 trillion USD in the Fresh Start initiative, thus supporting the Green New Deal. Moreover, a number of US states and corporations have entered into public-private partnerships to transform heavily coal-reliant states (Kentucky, Montana, Ohio, and Texas) into green energy hubs. This move generated a lot of discussions ahead of the 2024 US elections.

Deus Ex Machina

In 2035, a number of breakthrough technologies have become available to the public. This is the result of a period of growing private-public cooperation that began in 2022 and saw unprecedented levels of investment from both the public and private sectors. However, not all technology is accessible to the masses yet. While innovations drive positive developments (e.g., 3-D printed foods or the availability of GM seeds that require much less water), the deployment of technology is not always effective and, in some cases, the potential for conflict over access to water is even exacerbated. Farmers increasingly refuse to purchase efficient GM seeds (based on unsubstantiated health concerns and dis- or misinformation), leading to food shortages worldwide.

By 2034, new food technologies, such as vertical farming, are available but difficult to scale. Hailed as the future of the meat market, 3-D printed foods see an unprecedented level of investment, with $25 billion earmarked for the start of 2035 alone. However, 3-D food technology is only available to the wealthiest. Food insecurity remains a reality for millions worldwide, as technological solutions are not equitably shared globally.

As resource scarcity, land grabbing and the depletion of drinkable water intensify, the early 2030s see food and tech companies mainstreaming scalable technologies, including GM seeds. At the same time, dis- and misinformation on GM foods swamp social media worldwide and are further fueled by nations interested in destabilizing their regional competitors. Media illiteracy, frustration with economic inequality, climate fatigue, and social insecurities have propelled a burgeoning “anti-genetics” online movement, which disrupts major crop sales. In February 2031, Indian farmers from Punjab and Haryana burn GM crops from Bayer on the steps of the Indian parliament, despite early warning signals of a coming famine in Gujarat. Despite these upsets, investments in AgTech, which is seen as the “only way forward,” continue to rise.

Media illiteracy, frustration with economic inequality, climate fatigue, and social insecurities have propelled a burgeoning anti-genetics online movement, which disrupts major crop sales. Credit: Sion Touhig (via Getty Images)

Concerns over access to drinking water top the political agenda for many governments, particularly those in drought-prone areas. From 2025 to 2033, a US-Israeli private consortium joins forces to develop state-of-the-art weather modification tools to enable precipitation and safeguard Israeli food supply against “stolen rain” from the 2026 “Verdant Desert Initiative” that Israel’s neighbors introduced. By 2033, in a demonstration of state power, Geshem LLC launches in Tel Aviv. The company promises rain “on demand” for both nation states and Big Agriculture. The same year, climate and agriculture mitigation technologies provoke new controversies and receive record funding.

In 2030, Tesla has successfully implemented renewable energy networks in Texas, New York, Montana, and Wyoming. Meanwhile, the Chinese firm Evergrande has released a new fleet of electric cars that appear oddly similar to Tesla’s vehicles and has established a grid network in Shanghai. The rise in tech solutions for water scarcity issues (e.g., by Geshem LLC or through the Verdant Initiative) coincides with an expansion in green energy networks.

By 2029, investment in water futures have soared as news broke worldwide that underground water sources and aquifers would not sustain the 9.8 billion global population projected through 2050. Speculators are betting on the high price of California water futures and seize their outsized positions to control the market. Daily trade volumes reach a 100 percent increase from the same period in the previous year. In late 2029, Robinhood (a trading website popular on Reddit) halts all water futures trading, fearing speculation due to increasing investment in geo-engineering and weather modification technologies as well as ongoing water scarcity.

In 2029, investment in water futures have soared as news broke worldwide that underground water sources and aquifers would not sustain the global population projected through 2050. Credit: Muratart (via Shutterstock)

The years 2026 and 2027 have witnessed severe and prolonged droughts in the Middle East and other volatile regions. To avoid another Syrian War, Egypt, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates launch the “Verdant Desert Initiative” to expand investments in sustainable farming in the Middle East to nearly 1 trillion USD over five years, and to increase arable land through weather (precipitation) control techniques. While the underlying science has proven unreliable, tensions in the region escalate: although attribution for changes in rainfall patterns proves scientifically fraught, Israel’s right-wing government still blames the Verdant Initiative’s actions for shifts in the country’s rainfall patterns.

By 2026, global wildfires are becoming increasingly frequent. However, the year will mainly be remembered for the worldwide explosion in illegal logging, which sees an increase of over 200 percent that, in turn, results in timber futures skyrocketing by 1,000 percent. Financial systems are undertaking serious efforts to adapt to climate-related pressure. Over the next few years, micro-level climate insurances, like wildfire house insurance, become widely available. Nonetheless, the possibility of a global climate-related financial crisis looms large.

The climate crisis had picked up additional speed a few years before. From 2022 to 2027, a number of climate disasters hastened the search for technological solutions for adaptation and mitigation strategies worldwide. In 2025, South Africa experienced an unprecedented fifth wildfire season, prompting the Cape Town Conference to discuss wildfire risk mitigation as fires raged simultaneously in Australia, India, parts of Europe, and Russia.

Fractures and New Connections in a Multi-Polar World

By 2034, a number of coastal regions have flooded or sunk into the sea due to tropical storms, hurricanes and typhoons. Erratic monsoon rains have triggered unprecedented mudslides, burying tens of thousands of the most vulnerable people along different coastal areas. In Bangladesh, for example, thousands were left homeless, hungry and unaccounted for after a series of mudslides. Overwhelmed by the situation, the government in Dhaka demanded resettlement for the Rohingya in Myanmar, who had fled from persecution to Bangladesh in 2017. Other parts of the world began disappearing a few years earlier. After the Marshall Islands and the Maldives submerged in 2026, a series of hurricanes between 2027 and 2030 threatened the Caribbean. In 2028, a tropical system brewing north of Columbia quickly intensified, battering large parts of Jamaica, Anguilla, St. Maarten, Dominica, and the Lesser Antilles. Large sections of these islands were destroyed and their inhabitants killed. Over the course of these events, major global powers entrenched themselves in economic and technological competition, establishing alliances based on shared climate concerns.

In 2032, a special investigation by US and European intelligence agencies revealed that the Russian GRU (the country’s military intelligence agency) instigated the global online disinformation campaign against GM seeds, which resulted in global food shortages affecting the economically most vulnerable. Despite this revelation, farmers across Africa continued to refuse seeds sourced from Bayer for agrarian assistance, citing inconclusive health and safety issues, including claims that these seeds cause impotency.

In 2034, many coastal regions have flooded or sunk into the sea. Erratic monsoon rains have triggered unprecedented mudslides, burying tens of thousands of people in coastal areas. Credit: AJP (via Shutterstock)

Between 2030 and 2034, several economic and political developments culminate in the creation of international “Climate Clubs,” with countries collaborating on similar climate objectives and competing against the other clubs. In 2030, at the World Trade Organization (WTO), Tesla sues a Chinese conglomerate for corporate espionage, highlighting the sophisticated approach used to steal information from Tesla. A series of accusations and harsh exchanges between the US and Chinese governments follow, further entrenching competition between the two economic powers. Their respective allies strategically offer selective support. Other developments include the US and Japan cooperating on grid-bypassing systems, while China and the EU collaborate on 5G smart grids. The EU and China also enter into a bilateral treaty on climate refugees, while the US establishes a different climate refugee status as well as a global tribunal system for global ecocide. In addition, both the EU and the US implement a carbon border tax, thus alienating developing countries that lack climate ambitions.

By 2029, more countries have aligned themselves with either the US, China or third-party blocs. Regional alliances result in a securitization of newfound investment opportunities. Meanwhile, corporate espionage becomes ever more sophisticated, costing the global economy more than 5 billion USD annually and provoking deep mistrust between regional innovation hubs.

In 2028, after a series of climate disasters and abandonment from Western governments, capital cities across Southeast Asia voice their frustration with global climate governance. China announces that it will share geoengineering and weather modification technologies with its Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) neighbors and set up a climate relief fund for Southeast Asian countries. Further, a Chinese foreign ministry spokesperson alludes to Beijing’s consideration of revoking patent rights for weather modification technology to facilitate access for middle- and low-income countries.

In 2028, China announces that it will share geoengineering and weather modification technologies with its Southeast Asian neighbors and set up a climate relief fund for Southeast Asian countries. Credit: Mont592 (via Shutterstock)

From 2024 to 2027, catastrophic climate events have wreaked havoc worldwide. By 2027, the US-China competition in the climate race has advanced significantly, with the US focusing on the climate change-related impacts on its own economy and other domestic issues. Anticipating an opportunity to further assert its power, the Chinese government appoints itself to lead the global charge in climate change mitigation at the 2027 Shanghai Conference.

In 2023, after the COVID-19 pandemic, the EU is increasingly fractured and populist politicians face encouraging election prospects (such as Marine Le Pen in France in 2022). The US is concerned with domestic politics and social justice issues (including economic inequality, racial and gender equality, infrastructure, and public health), withdraws its troops from the “Forever War” in Afghanistan, and is actively grappling with China. In the post-Brexit world – and without a unified voice – the EU is repositioning itself and increasingly struggling to assert its place in global politics. China seizes the opportunity to intercede and enhance China-EU cooperation, including on 5G technology, smart grids and renewable energy that will increase jobs on the continent.

In 2022, following political developments and venture capitalist investments in the US and other countries worldwide, HSBC, BNP Paribas, Goldman Sachs, and other large international banks convene to agree on mandatory social costs on carbon, as well as metrics for valuations, discount rates and loan terms. Concerned with their personal legacy and credibility issues, extremely wealthy investors lead a push to update the Corporate Climate Social Responsibilities (CCSR) agenda for their investment banks.

In 2023, the EU is increasingly fractured and populist politicians face encouraging election prospects, such as Marine Le Pen in France in 2022. Credit: Frederic Legrand (via Shutterstock)

What Are the Main Implications of this Scenario?

Having explored the possible futures of Scenario I, the working group considered the most important implications and reflected on the following questions: How could the worst outcomes of the scenario be avoided and some of the worst consequences be mitigated? Who are the actors that can take action? And which steps should they take?

One implication of this scenario: private enterprises will amass further power and influence in shaping world events at both the local and global level. Credit: Matthew Henry (via Unsplash)

Mitigating Adverse Effects: Who Can Do What?

Snapshot of Scenario II

It is the year 2035 and climate change is considered the central challenge of the 21st century. A process of power redistribution from West to East is shaping the new global political landscape. Tensions between powerful countries (namely, the US and the EU on one side, and China and India on the other) are triggering occasional conflicts and promoting pluralist – instead of one unified – governance regimes. Overall, climate disruption is moderate due to a global acceleration of adaptation and mitigation measures adopted between 2022 and 2035 (specifically in the realms of renewable energy, afforestation, carbon capture and storage (CCS), value chain carbon footprint reduction, and circular economy). Nevertheless, global warming persists. As rising sea levels cause islands and coastal cities (such as Miami Dade County, Venice and Alexandria, to name a few) to disappear, an increasing number of people are evacuated or manage to retreat. Domestic migration is, for the most part, well organized. Those affected by climate disasters are usually relocated effectively. Undocumented international immigration, however, causes humanitarian emergencies to proliferate at the European and US borders, as government interventions strictly regulate and forcibly prevent cross-border migration, often through use of violence.

To meet the world’s growing food demands, technological breakthroughs enable farmers and farming companies to increase productivity through hyper-intensification and industrialized farming.

Due to overall global population growth, the agricultural sector is under significant strain. Production has become increasingly exposed to climate shocks, leaving small and individual farmers particularly vulnerable. To meet the world’s growing food demands, technological breakthroughs enable farmers and farming companies to increase productivity through hyper-intensification and industrialized farming. Technological advances are not only revolutionizing food production but also increasingly relied upon to combat climate change. Geo-engineering technology, such as CCS, is widely available to states and corporations. However, in some cases, it functions ineffectively, as the geological properties of the chosen storage sites are less promising than initial estimations had anticipated. States and markets are financially resilient and effective in their responses to climate shocks, which have mostly become predictable and manageable.

To meet the world’s growing food demands, technological breakthroughs enable farmers and farming companies to increase productivity through hyper-intensification and industrialized farming. Credit: Thomas Barwick (via Getty Images)

International cooperation has resulted in more effective and credible global governance regarding climate policies and climate-related conflicts, and it intensifies among countries within the same regional blocs. These alliances are formed based on their respective leading states’ political and economic power, which includes access to scarce natural resources, capital, military capabilities, and technological innovations. While these coalitions are not formed solely for the purpose of addressing climate issues, they evolve into alternate, pluralist governance regimes and provide a regional governance framework for climate change-related actions, including by facilitating access to climate technologies and investment capital and governing regional migration. These blocs negotiate on behalf of their members within larger geographical, economic and political alliances, usually led by powerful states (for example, China, India, Africa, Europe, and the US). Tensions between blocs are increasing due to competition over natural resources that are key to the global energy transition. Despite multilateral efforts to address this challenge, scarcities are becoming more severe, as the growth in consumption and production outstrips the availability of critical resources like rare-earth materials, fertile agricultural land and, in some parts of the world, water resources. Insufficient access to such resources drives the exploitation of deep-seabed minerals and the Arctic as well as support for space resource exploration (for example, on the moon and on Mars).

What Are the Main Factors Driving this Scenario?

A mix of climate, technological, political, and economic factors drives this scenario. While none of these drivers dictates the dynamic of our scenario, each one contributes to the future state of the world outlined above.

Climate change is increasingly mainstreamed as a global and local agenda, as public and private sector actors reach a tipping point regarding investments in climate-friendly technologies (including, among others, renewable energy, sustainable transport and circular production methods).

Climate change-related impacts are moderate (irregular climatic events, steady rise of temperature/sea level, etc.) and lead to some related migration.

China and India emerge as leaders in international climate politics.

Tensions emerge between blocs competing for scarce natural resources.

Populations and economies continue to expand. While we foresee a continued decoupling of growth and resource use, some resource scarcities remain.

Advanced economies with access to natural resources (such as China, India and the US) dominate the sphere of technological innovation.

Scenario II: Building the Great Green Wall

In 2035, the world achieves 100 percent clean and renewable electricity, continuing on a path toward decarbonizing the world’s economies. The 40th United Nations Climate Change Conference, which takes place that year, establishes new and legally binding obligations for the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) parties to achieve the goal of a maximum of 1.5 degrees of global warming. While this long-standing international climate governance body still functions as a forum for multi-national dialogues, the implementation of climate change-related actions has become largely delegated to different regional blocs. Divestment from fossil fuels reaches a critical point: Exxon becomes bankrupt, while BP, Equinor, Shell, and other former extraction giants now thrive as players in the market for renewable energy. Carbon offsets reach 500 USD per ton globally. A year earlier, in 2034, a stringent global carbon tax regime has been introduced: companies that have not achieved carbon neutrality by 2035 will have to pay a 50 percent income tax. Many Pacific Island states descend into chaos due to the adverse effects of different climate shocks. Their inhabitants are either evacuated to neighboring mainlands or migrate to “safer” areas within their respective islands (like Fiji).

In 2035, the world achieves 100 percent clean and renewable electricity, continuing on a path toward decarbonizing the world’s economies. Credit: Raimond Klavins (via Unsplash)

Meanwhile, the world’s population continues to grow – especially in parts of Asia and Africa – and reaches close to 8.9 billion people. As the global population expands, so does economic growth. In 2035, African economies drive 20 percent of global GDP growth. In 2032, food security has become a major issue as the demand for food increases globally. To meet this growing need, 70 percent of the world’s food is now produced in intensive farming factories near mega cities with large populations where substantial efficiency gains are being achieved. This hyper-intensification of industrialized food production increasingly strains natural resources. In 2031, the global water use footprint of the agricultural sector has already been reduced by 50 percent: still, food production increasingly depends on resource-intensive technologies, which are already in high demand due to the global energy transition that is underway. The development and deployment of battery-powered vehicles in the transport sector, for example, requires contested rare-earth materials, as well as copper, lithium and nickel.

In 2033, a Dutch-Chinese company has developed ships that run on batteries and can travel ten times faster than previous generations. Consequently, alternatives to long-distance flights will soon become commercially available. In addition, there is a shift toward green and ecological mobility in large cities, which changes the way urban populations move around. E-mobility dominates urban transport, with high-speed mass transit increasingly replacing individual modes of travel.

As 2032 approaches, climate change adaptation is increasingly mainstreamed due to the continuous effects of regular – albeit moderate – climate shocks. These include irregular climatic events as well as the steady rise in temperatures and, subsequently, sea levels. This mainstreaming effect is reflected in the upsurge in global climate investment, which reaches 5 trillion USD, while coastal cities and some islands have fully submerged, forcing their inhabitants to relocate. While international cooperation has achieved very effective results in some areas, cross-border migration is still considered a national security threat in Western countries and there is a lack of coordination on or international management of this issue. Nevertheless, cross-border migration cannot be completely prevented, which repeatedly results in humanitarian emergencies at different borders as well as sporadic, geopolitical conflicts. In parallel, countries begin forming regional alliances in response to region-specific needs and crises triggered by climate change. Some governments encourage or accept climate-driven movements of people within established bilateral and multilateral (but not global) quota systems.

There is a lack of international coordination on cross-border migration, which repeatedly results in humanitarian emergencies at different borders. Credit: CHANDAN KHANNA/AFP (via Getty Images)

Two years earlier, in 2030, South Africa introduced a national water pricing system. Many non-OECD countries are considering similar efforts, as pricing water is increasingly perceived as a crucial instrument for effectively managing and allocating water resources. Major upheavals are underway in the transportation sector as well: the last internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicle is sold in Europe. In the automotive market, electric vehicles now dominate the sector, while long-distance hydrogen fuel cell vehicles are projected to become cost-competitive within the next couple of years. In 2029, so-called “Climate Tech” companies are valued to have the highest market capitalization worldwide. Climate Tech refers to a broad range of sectors jointly working toward de-carbonizing the global economy, with the goal of achieving net-zero emissions. In 2028, all countries pledge to spend at least 5 percent of their national budgets on increasing “green cover” (i.e., a range of strategies to integrate green, permeable and reflective surfaces into cities and towns). By 2027, circular production methods and modes have become standard across sectors, leading to higher efficiency and the partial addressing of certain resource scarcities.

In 2029, so-called “Climate Tech” companies are valued to have the highest market capitalization worldwide. Climate Tech refers to a broad range of sectors jointly working toward de-carbonizing the global economy, with the goal of achieving net-zero emissions.

A year earlier, in 2026, India launched a 1 trillion USD global climate fund to finance investments in electro-mobility, hydrogen and public transport, as well as more productive farming. The Indian ‘climate package’ was inspired by the Chinese 1 trillion USD global climate fund, which was launched in 2022 and focuses on the clean energy transition, space exploration and climate resilience. In 2024, China launched the Asia-Pacific Alliance Against Climate Change initiative. China and India subsequently emerged as leaders in international climate politics, thus triggering competition with longtime economic front runners, such as the US and Europe. These vying powers begun forming blocs of alliances in economic activities and climate policies. That same year, Europe and the US implemented a global carbon tax regime that fueled geopolitical conflict between regional blocs, as China and several emerging economies promised to retaliate against this measure. International cooperation has intensified among countries within different blocs, while tensions between blocs rise. A handful of technologically advanced countries with greater resources (such as China, India and the US) now dominate the innovation sector. They leverage their technologies to form regional blocs and only permit access to their respective allies. In 2026, tensions rose between OECD countries and natural resource supplier countries, mainly in Africa and Latin America, over supplies of crucial battery materials (for example, lithium, cobalt ore and manganese), as these resources become increasingly coveted.

Major upheavals are underway in the transportation sector: the last internal combustion engine vehicle is sold in Europe. In the automotive market, electric vehicles now dominate the sector. Credit: THINK A (via Shutterstock)

As demand for these materials increases, new extraction frontiers are explored. This includes different seabeds, the Arctic and, most promisingly, outer space. The first initiatives are driven by the private sector, as Tesla joins forces with Indian company Antariksh to register plots on the moon in 2027. This move rattles European and US governments, which are witnessing the private sector’s progress in space exploration with growing concern and are themselves scouting greater space commercialization. The US, Europe, Russia, China, and India appear to reach consensus on a system to formalize mining and farming rights in outer space. At the same time, the African Union contemplates plans to establish its own space agency in the following year.

What Are the Main Implications of this Scenario?

Our scenario triggers certain questions regarding the main implications that follow from it for the possible global future(s) of climate-related conflict. Given the dynamics and constraints presented above, how can we achieve better outcomes? Who can take action? And what should these key actors do? How can climate-related conflict be mitigated or prevented?

To approach these questions, the fellows of this working group more closely investigated the possibility of regional blocs shaping the new multipolar world order laid out in this scenario.

Conclusion

How to reform existing global governance institutions so that they become more effective in negotiating the long-term approaches and interests of competing regional blocs remains a key question. Other vulnerable states that are excluded from these alliances are likely to form their own coalitions to maximize their political bargaining power against the major blocs. Multilateral organizations, such as the UN and other global fora, will need to reform and adapt to enact effective and efficient global governance, which will be increasingly important to mitigate climate change and establish adaptation measures commensurate with global warming levels – or at least prevent the most detrimental effects of extreme weather events and ecological disasters. Nevertheless, regional actors continue to assemble their own institutions (such as the Arctic Circle). This leads to the emergence of “parallel,” multilateral bodies that, on one hand, serve to address regional climate shocks and foster coordination on defense and security affairs.

On the other hand, these bodies increase the complexity of international politics, making global climate policy (even) more difficult. Regional bodies will face greater pressure to become effective institutions, compatible with increasing global interdependence on climate issues. Those organizations will also be relevant in other areas, such as security. Regional agreements on migration-related matters could address the movement of people driven from their homes due to both moderate (but sometimes extreme) climate-related shocks and economic reasons. As population growth continues, food production will also have to increase, which – given spiraling global inequalities, climate change impacts and escalating water scarcity – will likely require a certain level of technological innovation and creativity. Joint investments by states and sharing the rights to core technologies would be beneficial for advancing AgTech and Climate Tech globally. Proliferation of already-available technologies for climate mitigation and adaptation will also reduce the pressure on countries without access to such innovations. Reducing greenhouse gas emissions, scaling up circular means of production and consumption, as well as further decoupling of growth and resource use can reduce tensions regarding resource access within as well as across blocs based on the assumption that less scarcity will result in less competition.

No comments:

Post a Comment