Robert Farley

Where will the next 9/11 fall? This question dominated American security thinking for the seventy years prior to September 11, 2001. The answer is likely less surprising than we think.

12/7 and 9/11

The US national security state experienced two shocks seventy years apart that effectively recreated our systems of intelligence and preparation. The differences between September 11 and December 7 remain stark; one was a terrorist attack, the other a strike against military units. December 7 resulted in a long, costly great power war that was nevertheless successfully concluded with a decisive victory. September 11 resulted in a series of costly, indecisive, and ultimately unsatisfying conflicts.

Despite the closure offered by the successful execution of a war-winning campaign, December 7 had an immense and enduring effect on US strategic culture. In 1947 the US restructured its security institutions in order to prevent another December 7. The need to do so was driven not just by the disaster of the Japanese attack, but also by the belief that nuclear weapons would make another such attack much more devastating. The reforms included most notably the creation of a permanent intelligence community, a step that most European countries adopted in the early 20th century but that the United States had resisted. They also included the creation of a Department of Defense which could better coordinate activity across land, sea, and air.

There was no similar reconstruction of US security institutions after September 11. The changes made were mostly cosmetic and generally inconsequential to the functioning of the security state. The biggest legacy of 9/11 is less the institutional structure of government and more the reach of the state into society. This was driven as much by technological change (the explosion of social media and the digitization of social and economic life) as by intentional state policy, but still resulted in a costly extension of the power of the state, costs that were largely born by vulnerable populations.

The reforms of 1947 and the extension of those reforms in 2001 may or may not have accomplished their goal; the expected catastrophes never occurred, although whether they were prevented or simply never all that likely is a different matter. But in the long term, another shock to the system is inevitable. What might the next 9/11 look like?

Sometimes It’s Who You Most Suspect

Neither 12/7 or 9/11 should have been shocking. The US knew that war with Japan was likely and that Tokyo would strike the first blow in 1941 or 1942. Washington was acutely aware of the threat of Al Qaeda terrorism in 2001, even if the attention of the government had drifted. What surprised the United States was not that the blows fell, but rather the magnitude of their impact.

War with China is unpleasant to contemplate, but it is not impossible. The tactical and political conditions of the Western Pacific suggest that if war were to begin over Taiwan or for some other reason, China would very likely draw first blood. It would be nearly impossible from a political point of view for the United States to initiate military operations against the PRC. While the alliance structure of the Western Pacific is not nearly as institutionalized as that of NATO, the diplomatic fallout of US aggression would be devastating. Moreover, the destruction of US bases and aircraft carriers in a surprise attack would give China the freedom to seize Taiwan or whatever other target it has in mind. Thus, as in 1941, the US must prepare to weather the first blow; in some sense, it has become China’s job to make that blow as intense as possible, and the US job to minimize its effects.

But Sometimes It’s Not

For two generations Americans expected that war with the Soviet Union could begin at any time, and that it would likely begin with a devastating nuclear attack against the American homeland. Military analysts believed that Moscow might launch a surprise conventional offensive through the Fulda Gap, hoping to rapidly overrun NATO forces and throw the US off the continent. For their part, the Soviets worried constantly about a decapitating nuclear attack that would destroy the leadership in Moscow, effectively a nuclear version of the events of June 22, 1941.

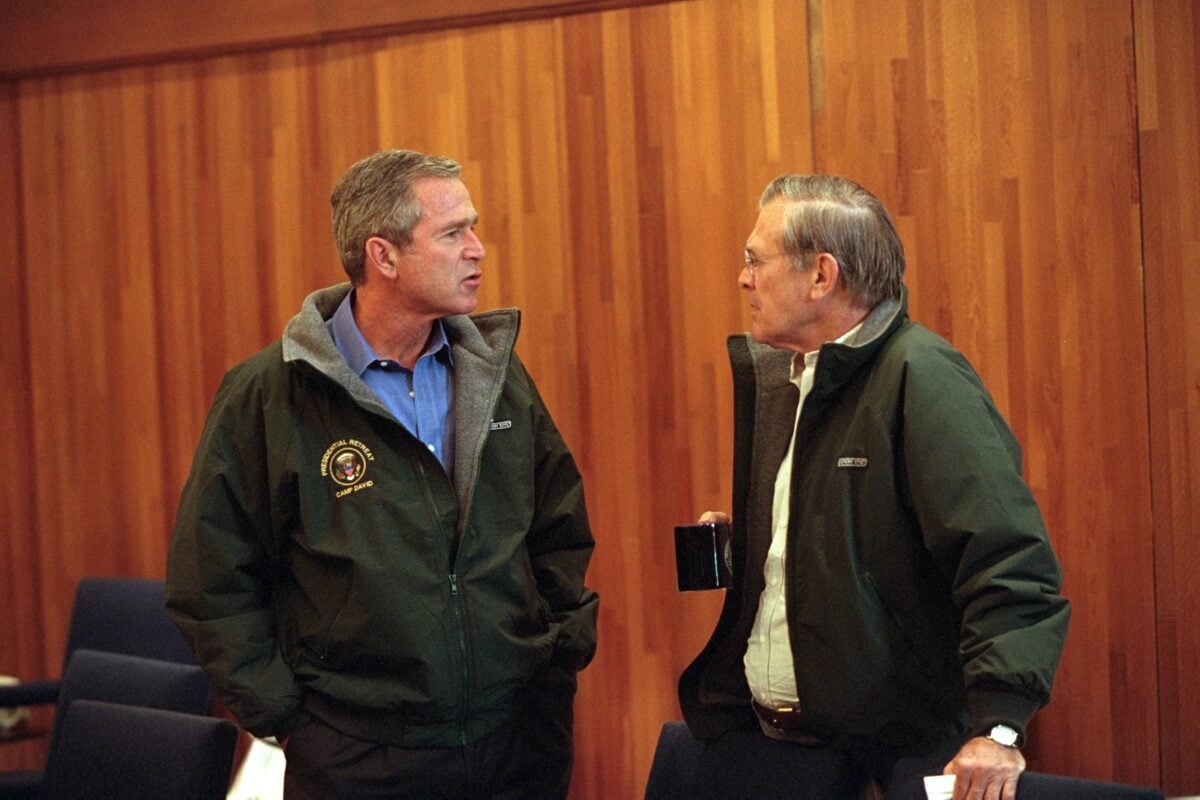

President George W. Bush talks with Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld Saturday, Sept. 15, 2001, during a break from a National Security Council meeting at Camp David in Thurmont, Md. Photo by Eric Draper, Courtesy of the George W. Bush Presidential Library.

Preparation for a surprise is always sensible, but both the US and the USSR paid enormous costs in order to minimize the impact of an attack. They arguably made the world more dangerous by placing their military forces on hair-trigger alert, meaning that a single mistake could have had unthinkably devastating consequences.

Parting Thoughts

The United States was not prepared for either December 7 or September 11, although in both cases it probably should have been. The next catastrophe will not come from an unknown assailant, but rather in an unexpected way with unexpected effects. At the same time, Washington must be cognizant that over-preparing for the next shocking attacks carries a different set of costs. There is no easy answer to this dilemma; it is an enduring problem of national security statecraft.

No comments:

Post a Comment