Antonia Colibasanu

Last week, I spoke and moderated at several conferences in person – a rare thing since the pandemic began – whose topics ranged from defense and security to regional commerce to European affairs. The common denominator, of course, was geopolitics, but what struck me most about my conversations was that, rather than the withdrawal from Afghanistan or the elections in Germany, nearly everyone was concerned foremost by inflation and the green economic shift underway in Europe.

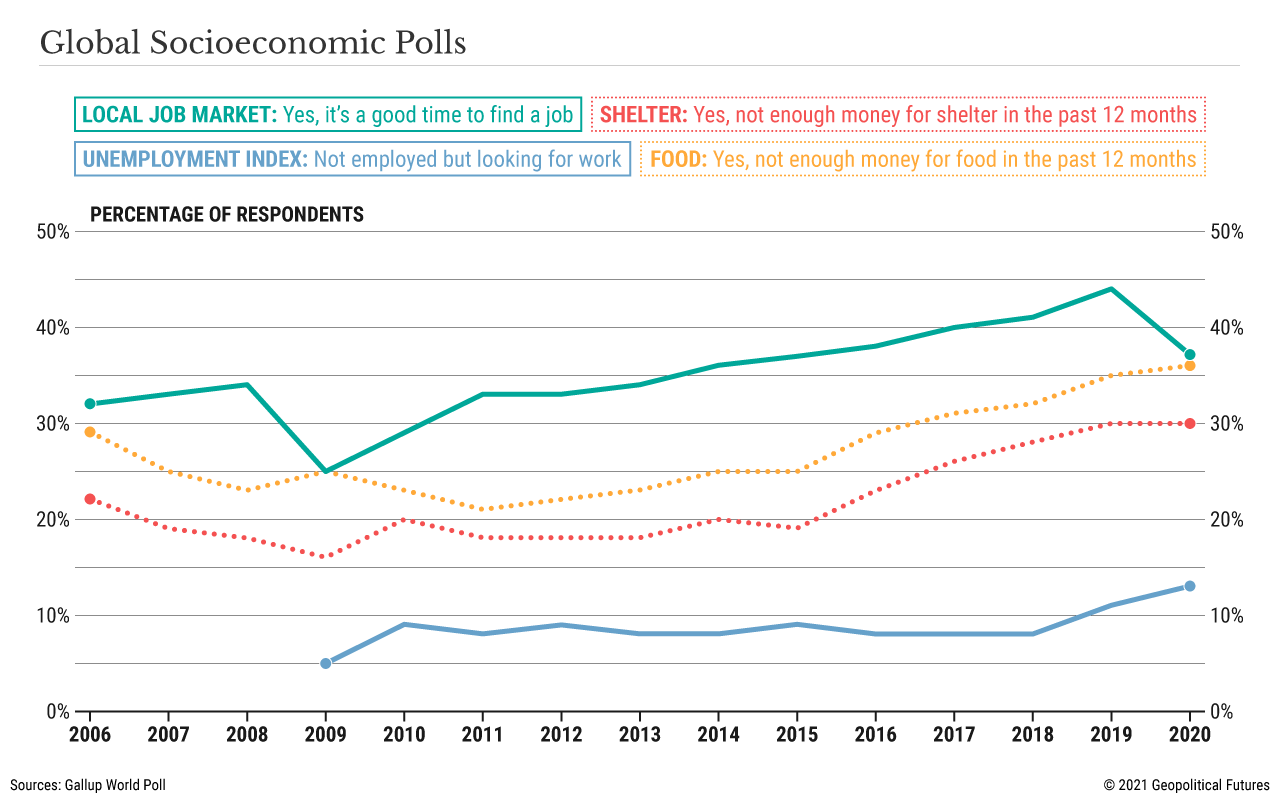

In fact, nearly every conversation had one thing in common: Our society’s economic challenges in light of the pandemic. Until August, inflation was generally triggered by the energy sector and by a narrow set of goods such as semiconductors whose price increases were linked to the supply chain crisis. But, as evidenced by recent upticks in food and services prices, it seems as though the effects are widening. Bad weather conditions, unusual droughts and floods that destroyed harvests, often cited as the collateral damage of climate change, have contributed to an increase in food prices.

And though that was the case even before the pandemic started, the pandemic has indeed exposed the vulnerabilities in the food system, impacting production, supply and delivery. Increased ocean freight rates, higher fuel prices and a shortage of truck drivers are pushing up the cost of transportation services. Moreover, the pandemic created difficulties for producers to access the labor force they need to get crops delivered in due time (to say nothing of the workers needed to deliver and distribute other goods). Such was the case for tomatoes, oranges and strawberries producers in Europe in 2020. In Australia, industry groups fear that pandemic-related challenges could derail what is expected to be a stellar crop of winter grains this season.

The food industry is hardly the only industry grappling with these kinds of challenges. An explanation put forward by HR specialists cites the fact that there seems to be a mismatch between the industries hiring and those seeking jobs, a development apparently borne out by the uneven recovery in different industries. Another explanation refers to the fact that, during the pandemic, many workers moved away from the cities where they worked, leaving their jobs unfilled until there is a better sense of when the pandemic may subside. This speaks to the importance for the workforce to be able – and willing – to migrate from one place to another.

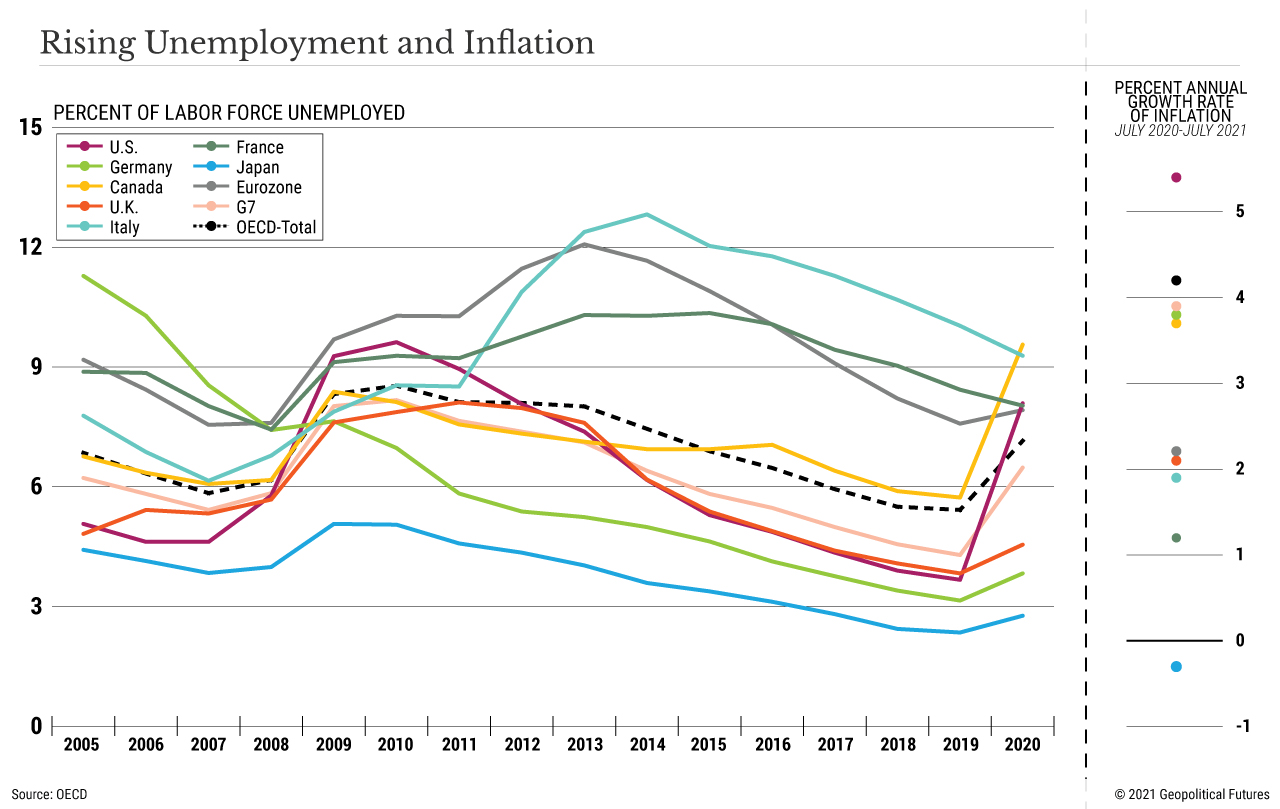

For the first time, we’re seeing both high unemployment and high inflation – something that is abnormal when economies are recovering from recession, and just generally abnormal. Inflation typically comes alongside recovery and growth, which typically lowers unemployment. The problem is that inflation is unbalanced: There are too many jobs and too few people willing to take them.

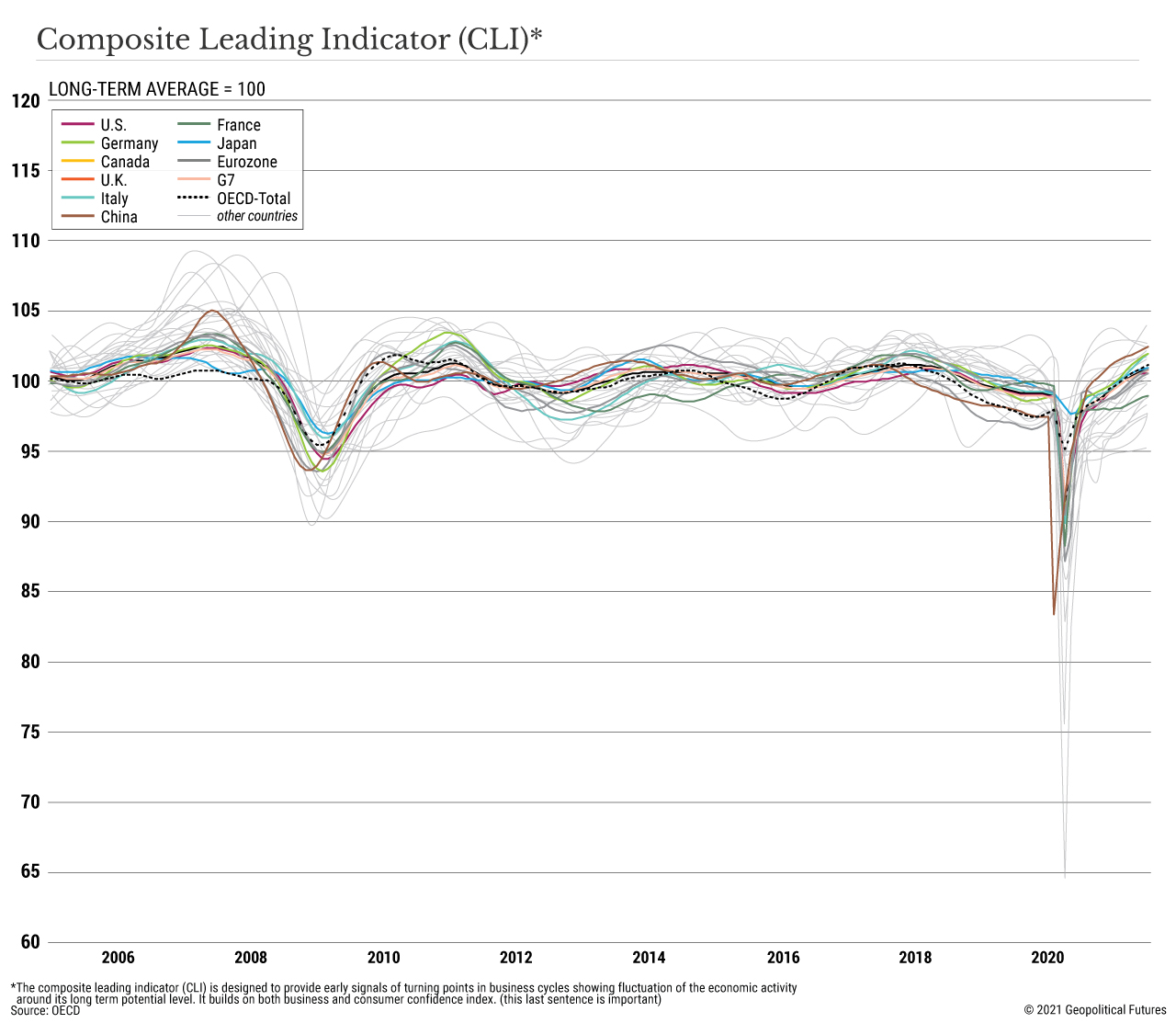

The summer of 2021 has been anything but normal, of course. The pandemic is not over. The Delta variant, combined with low vaccination rates, has pushed COVID-19 infections up again and has thus slowed the service sector’s recovery. In addition to supply shortages cutting into both consumer and business spending worldwide, a steady wave of grim news concerning Afghanistan, global political stability, and also extreme events like hurricanes and wildfires have eroded consumer confidence.

Confidence is essential for an economy to function. The pandemic has shown once more how vulnerable our current social system is. As with the 2008 global financial crisis, people are witnessing firsthand the negative effects of globalization, even as they reconcile the fact that interconnectivity and interdependency are realities that cannot be quickly undone. It’s only reasonable that they question the current rules of the game if those rules create pain and suffering.

And, after all, it is the people’s tolerance for pain that triggers political change. With so much general discontent with the way that the global system works, the idea that there is something inherently wrong with our society has in its own way advanced the conversation on sustainability and climate change. The perception that we live in a fragile world demands that we ask our governments to fortify our very existence – all while stabilizing the economy. To be sure, it’s a radical change, one that requires socio-economic restructuring.

From a geopolitical point of view, states are asked to make use of their economic power to secure safe and stable living conditions for their people. This has long been the case, but the urgency of needed changes at a time of intense international economic competition makes for the transformation of geopolitics into geoeconomics. The traditional meaning of geoeconomics is that nations employ foreign trade tools to achieve imperatives. In the current context of deeply uncertain times – thanks to the pandemic, climate change and the digital revolution – the geoeconomic function of the nation-state refers to making use of economic tools to achieve political goals and to increase the nation-state’s power. Controlling the markets, managing trade surpluses and making use of economic sanctions or strategic investments to enhance political influence are part of the arsenal a country can use to build, maintain and increase its economic power.

But what is economic power? How can we measure it, given the complexity of the pandemic times we live in? Real gross domestic product growth and trade dependencies give just some basic ideas of the economic stability of a country. With the pandemic, we have learned that the power of disposition over strategic raw materials plays an important role in keeping strategic sectors alive. What constitutes a strategic sector, and therefore a strategic raw material, also changes by location and time. Oil is not as powerful now as it was in the 1970s. Water supply, while essential for everyone, is more strategically valuable in some places than others. Extreme phenomena attributed to climate change also pose specific questions in the longer term. The ability to produce technological innovation will give countries influence over critical infrastructure and therefore enable them to secure their stability in times of extreme events such as droughts and pandemics.

At the same time, the ability for a country to enforce international standards and norms is key to setting the rules for the global economic system and for exerting influence over other states. With globalization, we already have countries using different norms operating in the same market economy, but accessing strategic markets is still difficult due to the prevalence of Western-based standards.

There are therefore three elements a state should focus on in building its geoeconomic strategy. First, it needs to retain the economic strength it currently has. Second, it needs to reduce one-sided economic dependencies. Third, it needs to develop a strategy that captures and expands on the value of its economic strength. In taking these three steps, the state focuses on defining its economic strengths, which are ultimately shaped by the population. The state’s human resources are its most valuable asset for geoeconomic strategy, particularly in uncertain times.

This is why the unstable relationship between inflation and unemployment needs to be taken as a serious signal of economic restructuring. Human behavior wrought by human pain is potentially triggering a revolution that could change the rules in the global system.

No comments:

Post a Comment