Jesse Colzani

Bitcoin – the most secure and well-established technology to store value[1] – was created in 2008 to challenge the state’s centralised monopoly on money. It is a digital currency worth 1 trillion US dollars that knows no boundaries and is not controlled by any central authority. Although it is considered a threat to the established order, countries and institutional actors are gradually realising Bitcoin can also be a tool to advance their economic and geopolitical interests.

Today, governments find themselves in the difficult position of having to decide whether Bitcoin should be integrated into their economies and governance structures or if they should continue to oppose, block or seek to co-opt the digital currency. But to understand Bitcoin and make an informed decision, one has to first appreciate the different components of its ecosystem.

Bitcoin mining

Bitcoin is not only a widely distributed database. Like any other internet technology, it runs thanks to a network of machines which rely on an energy infrastructure of significant proportions. It is no coincidence that the way new bitcoins are produced is defined as “mining”:[2] if traditional mining consists of the extraction of resources from Earth, bitcoin mining can be considered the extraction of resources – coins – from its network. The mining process is an essential aspect of Bitcoin’s functioning: it is only by pooling computational power globally that trust in the whole system can be built and maintained.

Bitcoin mining activities recently became anti-economical in most areas of the world. This is because it requires huge amounts of electricity, specialised hardware and adequate temperatures to prevent machines from overheating. Areas where electricity is cheap and where temperatures are low enough are ideal for such practices.

Thanks to its proximity to hardware manufacturers, shorter supply chains, reduced shipping fees and lower import tariffs, Chinese miners enjoyed a considerable competitive advantage.[3] Indeed, until June 2021, China accounted for an estimated 65 per cent of Bitcoin’s mining power,[4] with the remaining share coming from the United States, Iran, Kazakhstan and Russia.

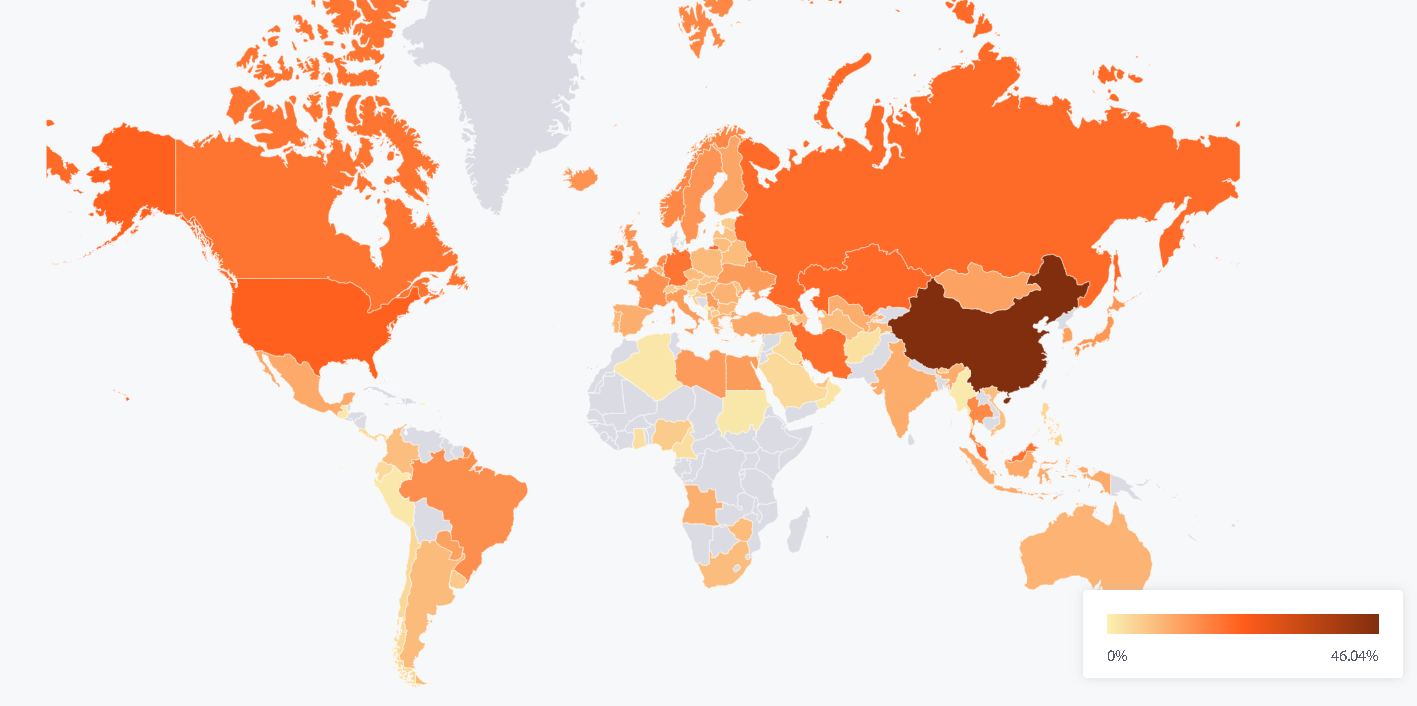

Figure 1 | Average monthly share of bitcoin’s total hashrate, April 2021

Source: Cambridge Bitcoin Electricity Consumption Index (CBECI) website: Bitcoin Mining Map, https://cbeci.org/mining_map.

Beijing, however, has recently implemented stricter policies to ban mining activities. The move is justified by the perceived threat that Bitcoin poses to monetary sovereignty, by a related hardship to enforce anti-money laundering policies, as well as by the Chinese ambitious plan to become carbon-neutral by 2060.[5] A Chinese crypto-exodus followed thereafter, leading to a significant redistribution of mining companies to other areas such as China’s neighbour Kazakhstan or crypto-friendly and energy-rich Texas.[6]

Most of the Bitcoin community has welcomed China’s crackdown since centralisation of mining has been a concern for a long time due to Bitcoin’s traditionally de-centralised structure and China’s historical political will to create its own central bank digital currency to challenge the US dollar dominance.[7] The Chinese exodus has also been welcomed because Bitcoin mining uses considerable amounts of fossil fuels, especially in coal-rich regions such as inner Mongolia. It is no secret that the electricity required to run the Bitcoin network is significant: Bitcoin currently consumes between 20 and 300 terawatt-hours per year. That is almost equivalent to the yearly electricity consumption of Belgium and the Netherlands.[8]

Yet, before dismissing Bitcoin as an unsustainable solution, it is worth having a better look at the data. A recent report estimated that “mining’s electricity mix increased to 56% sustainable in Q2 2021”, arguing that Bitcoin is “one of the most sustainable industries globally”.[9]

Moreover, Bitcoin appears to be greener than the industries it aspires to replace, such as gold mining and the banking industry.[10] Also, Bitcoin increasingly uses resources that would otherwise be wasted – like flared gas[11] – and gives strong incentives for miners to move to rural areas where renewable energy is cheap. As a result, some argue that Bitcoin will facilitate the transition to a cleaner, more resilient electric grid.[12]

Bitcoin exchanges

While originally embraced as a means to bypass traditional financial intermediaries, in an ironic twist of fate Bitcoin has now paved the way to a new and very powerful category of middleman: cryptocurrency exchanges.

Exchanges currently constitute one of the most “attractive regulatory access point” in the crypto world.[13] Just like the mining centres, these businesses are established in the most convenient areas. But it is the regulatory framework that matters most. Since it has the highest number of users and trading volumes in the world, the United States currently hosts most cryptocurrency exchanges, but a number of other crypto-friendly jurisdictions such as Malta, Hong Kong and the United Kingdom also emerged, attracting more exchanges to their territories.

The role of these companies is to convert customers’ cryptocurrencies into conventional fiat money and vice versa. Through this process, they manage up to 50 billion US dollars per day in Bitcoin transactions and have been growing in value and power.

Most exchanges collaborate with regulators and have sound regulatory compliance frameworks for anti-money laundering and fiscal purposes. Bitcoin exchanges manage about 10 per cent of the total supply of Bitcoin, while the remaining 90 per cent is potentially escaping regulatory scrutiny by authorities.[14] In the long run, exchanges could constitute an ideal regulatory bottleneck for governments but only if significant percentages of users will decide to use them.

Towards a Bitcoin standard?

Crypto exchanges and mining companies are consequences of the widespread adoption of Bitcoin. With Bitcoin slowly infiltrating the global economy, some have speculated that it could eventually become the world’s reserve currency, thereby challenging the supremacy of the US dollar.[15]

Currently, the high volatility of the world’s first cryptocurrency does not make such an outcome desirable, since its value is still dependent on large speculative activities, unconfirmed news and Elon Musk’s tweets.[16]

Yet, the limited supply of 21 million coins (or 2,100 trillion Satoshi – the smallest units of a bitcoin) and very low transaction fees make it an interesting alternative to traditional assets and currencies. It is on this basis that sovereign states are slowing warming to the idea of embracing Bitcoins as an alternative – parallel – currency.

One such example is El Salvador: a country that was using US dollars as national currency, where 70 per cent of the population is unbanked and where 20 per cent of GDP comes from international remittances.

El Salvador is the first and only nation in the world to adopt Bitcoin as legal tender. Citizens are now able to pay their taxes and purchase goods using bitcoins. President Nayib Bukele’s move in June 2021 has been widely criticised by financial institutions: the International Monetary Fund recently defined it as an “inadvisable shortcut”[17] and the World Bank rejected a request from El Salvador to help with the implementation of Bitcoin as legal tender.[18]

It is not clear whether the move should be considered part of a de-dollarisation plan and if El Salvador’s economy will benefit from the adoption of Bitcoin. But there are good chances that other dollar-dependent countries will act similarly – for example, the government of Cuba recently announced it will legalise cryptocurrency transactions in the country.[19]

While it seems unlikely that most governments and central banks will accumulate bitcoins in the short term, the private sector has been less sceptical. Companies such as Tesla, MicroStrategy and Square are adding billions of dollars in bitcoins to their balance sheets.[20] There is speculation that big companies such as Twitter, Amazon and Apple will do the same or accept Bitcoin payments from their customers.[21]

To understand how much the private sector is invested in cryptocurrencies, it’s enough to look at how the 1 trillion US dollars infrastructure proposal approval by the US senate was blocked because of concerns about how the government would regulate cryptocurrencies – a powerful effort from a crypto industry that invested 5 million US dollars in crypto lobbying this year.[22]

Meanwhile, about 80 per cent of the world’s central banks are exploring the possibility of creating their own central bank digital currency (CBDC).[23] In the short term, this will create competition between different state-backed currencies but also with the original cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin, which are a-national by nature. It is crucial to understand that, in this global race for digital currencies, CBDCs will represent a more efficient version of traditional state-backed currencies, while Bitcoin represents a new universal and decentralised currency.

Governments are slowly understanding that regulating Bitcoin per se would be almost impossible. Bitcoin is both everywhere and nowhere, and authorities cannot enforce laws both within and outside national borders. Bitcoin has no servers that can be shut down, no chokepoints and no single individual is responsible for the network.

Only a global and carefully coordinated regulatory approach could ensure a certain degree of control. But not only would this require a coordinated compression of individual freedoms (e.g. restrictions on Internet Service Providers or mass surveillance), but also a truly multilateral approach,[24] which currently seems difficult to envision.

Rather than attempting to regulate, co-opt or limit the technology, states should carefully consider their options and foresee possible future scenarios. If the value of Bitcoin can increase tenfold as some predict,[25] it makes sense for a country to acquire some amounts of it as a reserve.[26]

Figure 2 | Price of bitcoin in US dollars, 2013–2021

Note: A logarithmic scale is used for the y axis.

Source: CoinMarketCap website: Bitcoin, https://coinmarketcap.com/en/currencies/bitcoin.

Governments can individually implement policies to attract bitcoins and crypto-related investment opportunities into their economies. Local authorities are well-positioned to negotiate favourable agreements with mining companies to invest in rural and underdeveloped areas while cutting carbon emissions in the industry. Crypto-friendly regulations could increase the amount of Bitcoin-related businesses that are established in a country, which in turn can attract more investments into the country’s economy and allow governments to have more control on the economy.

Ignoring (or trying to block) Bitcoin constitutes a risk for states. These could miss an opportunity that could benefit their country and economy but there is also the risk of falling behind other countries and the private sector.

Small countries that may like to follow El Salvador’s example could do so in an effort to become less reliant on global powers such as the US and China, while attracting investments to strengthen their energy infrastructure. Conversely, larger economies have the opportunity to increase international capital inflow and consolidate their influence over other countries by offering services such as Bitcoin exchanges.

Bitcoins will continue to grow and expand and may thus move to challenge the role of the US dollar. Some even predict Bitcoins to replace the US dollar altogether. As far-fetched as that might sound today, the consequences would be cataclysmic in multiple ways, from geopolitics to the global economy and power relationships between states. The crypto-clock is ticking, and to avoid being caught off guard, governments need to have a plan that takes into account the success of Bitcoin and its likely future trajectories of growth and evolution.

No comments:

Post a Comment