Jennifer Griffin

"So my commander said, hey, you guys, the report's due to the chairman by noon. It's not ready yet. Go back to your desk, get these reports ready for presentation," Gunz recalled. "I sat at my desk, and then a massive explosion occurred. Windows shattered around me. I fell off my chair. My computer came down. There was confusion as to where the explosion was. I had been near explosions before, but inside the building, I couldn't tell where it was from."

Pete Gersten was a major in the Air Force one corridor away from where the plane hit the Pentagon. (Pete Gersten)

He grabbed his top secret computer, trained to protect it at all costs.

"We turned around and someone opened the front door to our vault and smoke just billowed into the room," he recalled.

"But the smoke started to fill the room to a point where I couldn't see where I was going. So I just threw the computer down and made my way out."

The memories come flooding back as if it were yesterday.

"The more I ran towards the center, the more I actually was running towards the center of the wreckage of the plane. So it got worse and worse and worse and darker and darker," Gunz said.

"As soon as I got near the edge of the outer door, I could smell the fumes from the jet fuel had been burning and the smoke was basically covering my uniform."

Gersten deployed the next day to the Middle East and became a key part of the development of a weapons system that would become the signature piece of the war: remotely piloted aircraft or drones – a new form of modern warfare which would define the next 20 years.

These unmanned aerial vehicles were armed for the first time after 9/11 with hellfire missiles. Predators, Reapers: Their surveillance became a key tool in the war on terror.

Pete Gersten poses next to a drone. (Pete Gersten)

"We grew that system to an immense scale. And we've been using those magnificent machines in this counterterrorism role ever since then. They're an extremely exquisite system built for missions like this. They are persistent. They can stay airborne for up to twenty-four hours. They are surveillance systems. If called to, they can strike in a moment's notice," Gunz said.

But for Gersten, like all of those U.S. service members who deployed after 9/11, six combat deployments came at a cost.

"My first daughter was born about four months after 9/11, my second daughter was born then 14 months after that. … Multiple birthdays missed, multiple Christmases missed," Gunz recalled.

"My first daughter was born about four months after 9/11, my second daughter was born then 14 months after that. … Multiple birthdays missed, multiple Christmases missed."— Pete Gersten, U.S. Air Force veteran

What would he like to tell those college-aged daughters now?

"The question they'll ask is, is, did you leave it better than when you got there. It's not as clean as one would think to answer that question," he admitted, especially in the wake of the recent withdrawal from Afghanistan.

"My response to my daughters when they asked me that question about what I was doing while they were growing up and missing half their birthdays was I am pretty sure I kept some bad things from happening and defended America and kept it safe."

Pete Gersten with his daughters as young children. (Pete Gersten)

‘Deployment after deployment’

Jason Redman was a Navy SEAL on 9/11 - he and his wife Erica know firsthand how the last 20 years of war changed the U.S. military and those who served. In 2007, in Anbar Province, he and his SEAL unit were ambushed.

"Myself and other teammates were all shot up. I was hit eight times between the body and body armor. I took a round directly to the face and was pinned down," Redman told Fox News. "We called rounds directly on our position and miraculously survived. And fast forward about 96 hours from that moment. I found myself in a hospital bed in Bethesda."

The doctors at Bethesda Naval Hospital, now Walter Reed National Military Medical Center were speaking in hushed tones at the foot of his bed.

He heard them say: "We're thinking about amputating your arm, your trachea wired shut. We're feeding you through a stomach tube. It's going to take years to put you back together. You have no use of your left hand from the nerve damage."

He could hear the doctors, even through all the pain killers and drugs.

"It was a conversation full of a lot of pity. And they were like, hey, you know, what a shame. What a pity. These individuals are never going to be successful again. What was this worth it? We sent these people off to war and they'll never be the same," Redman recalls.

His wife returned from getting a cup of coffee and he told her to put a sign on the door which he dictated.

"I wrote out that sign that said, ‘Attention to all who enter here. If you're coming to this room with sadness or sorrow, don't bother the wounds I received. I got in a job that I love doing it for a country that I love, defending the freedom, doing it for people that I love, defending the freedom of a country that I deeply love. I will make a full recovery."

What is full, he asked. "That's the absolute utmost I have in my ability to recover. And then I'm going to push that about 20 percent further through sheer mental tenacity. This room you're about to enter is full of optimism and intense rapid regrowth. And if you're not prepared for that, well go elsewhere."

"This room you're about to enter is full of optimism and intense rapid regrowth. And if you're not prepared for that, well go elsewhere."— Jason Redman, former Navy SEAL

His words were framed and left on the walls of Walter Reed for successive generations of wounded Special Operators, sailors, Marines and soldiers to read.

Jason Redman stands in uniform beside the sign that was posted outside his hospital room. (Jason Redman)

Few had more repeated deployments than the Special Operations community after 9/11, another part of the U.S. military transformed by a global war against suicide bombers and a brutal ideology.

"We became the go-to for everything. And what ended up happening is just it was deployment after deployment, after deployment," Redman recalled. "I know guys in the SEAL teams. I mean, I think the record that I'm aware of as a guy that did 16 combat deployments and the toll on that is tough."

These deployments and the life-altering injuries affected his children and all of the families of those who volunteered to serve.

"My friends would be over at the house and my kids would be around individuals missing limbs or recovering from war wounds, just like I did. And this is what my kids grew up with. So this was the post 9/11 Special Operations world that we lived in and that my kids grew up in," Redman said.

‘Never again’

Ramón Colón-López is a U.S. Air Force Tier 1 pararescueman who currently serves as the Senior Enlisted Advisor to the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs. He deployed to Afghanistan with SEAL Team 6 in the days after 9/11 and served multiple tours there. Colón-López was part of the team that escorted Hamid Karzai into Kabul and saved his life at one point.

The morning of 9/11, he was in Virginia Beach, Va., with his SEAL Team. He joined a group from his team who had already seen the first plane crash into the World Trade Center.

"I turned around and I witnessed it, the second plane hitting the towers. From that moment on, everything was dropped, we went out to our cages where we have our equipment and just got ready for what was coming," he remembered.

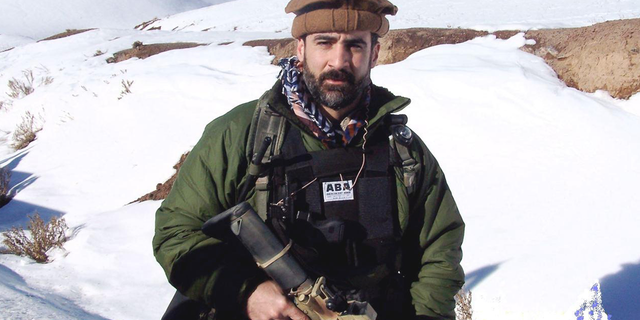

Master Sgt. Ramon Colon-Lopez on deployment as a pararescueman with the U.S. Airforce. His gear in this photo is now displayed on a mannequin at the National Museum of the United States Air Force in Dayton, Ohio.

"The anger I felt after the terrorist attacks, it just fueled me to just go ahead and do anything and everything possible to prevent that from ever happening again," Colón-López said.

"From that moment forward, there were many of us, I mean, close friends, that trained to a very high standard, just to make sure that we did not get the mission wrong. And to get justice for what was done. Every single one of us regardless of age, demographic service, specialty, had one mission, and that was to prevent that from ever, ever happening again," he said.

"Never again will American soil be attacked to that magnitude. And it just became an expectation for every single one of us. It wasn’t a matter of if, then, it was a matter of when. And a matter of when became, I need to go again, and again and again for 20 years."

Was it worth it?

"I would tell you this, America is at its very best when things are at its very worst," Gersten said emphatically.

"We unequivocally made a difference," Redman added.

"There are so many Afghans who got to achieve freedom. And I think and they've tasted it and they still want it. And I think about how America came together after 9/11, and I think we need to reinvigorate that."

"My message to my special tactics, brothers and sisters, is don't let anyone take your honor and your pride away for everything that you did over the last 20 years. Because one sentence at the end of the book doesn't rewrite the whole book," said Colón-López.

"I think about how America came together after 9/11, and I think we need to reinvigorate that."— Jason Redman, former Navy SEAL

With all U.S. troops out of Afghanistan, is the war finally over?

"I think special operations will always play a heavier role in the war years to come," Redman said. "But we also have to balance that so we don't burn out these forces. And I think we've seen some of that over the last several years of this 20-year war."

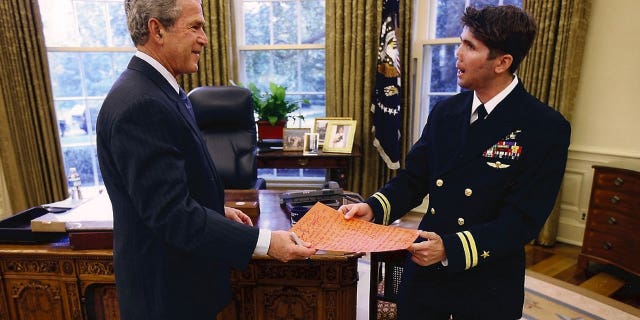

(Redman meeting with President Bush.)

General Joe Dunford was at Camp Pendleton on 9/11 deployed with the Marines to Iraq and rose to command all U.S. forces in Afghanistan for 2 years before becoming Chairman of the Joint Chiefs for the next 4 years.

"There's people who would suggest that maybe we should have been out of Afghanistan a long time ago," Dunford told Fox News. "And the way I've described it is every day that we were there, we were providing an insurance policy to protect the American people from an attack."

"We have to remember that the violent extremists that attacked us on 9/11 are still out there and that ideology is still out there. And I have no doubt in my mind that what's happened recently in Afghanistan will serve as an accelerant for extremism around the world."

Just days after the last troops left Afghanistan, the current Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, Gen. Mark Milley, reflected on 9/11 and what it means 20 years later, while standing on a tarmac in Rota, Spain with a blue and white plane with United States of America emblazoned on its side.

"We prevented the United States of America from ever being attacked again. There's a lot of conflicted feelings out there, and I'm included in that. A lot of conflicted feelings with pain and anger, we all have it, every one of us that served there has that," Milley said.

"I want everyone out there to know that the pain, the anger, the frustration, the conflicted feelings are real and I know that and I share them. I also want you to know it wasn't in vain, your service mattered and if you wore a uniform your service mattered."

No comments:

Post a Comment