Ullekh NP

In Delhi’s Ashram area where she has lived for the past three years with her family comprising parents, brothers and husband, Rabia (name changed) serves me tea and cheese, recalling in accented Hindi how traumatic it was to live in Afghanistan since the time she was born. Her parents are from ‘elsewhere’, she doesn’t remember where, but she was raised in Bamiyan, which was home to the giant 1500 years old Buddhas carved on a mountain that were destroyed by the Taliban in 2001. “Even our men were always made to feel they were outsiders. They thought our womenfolk are meant to be slaves, which was why I discontinued my studies after class XII,” says the 30-year-old, explaining the agony of being born a Hazara and also a woman in the landlocked country ravaged by wars.

Some of her relatives are in Bamiyan and their plight due to the Taliban’s return to power, her brother Rashid says, is like being a goat in front of a pride of lions. “Nobody respects us. Everyone is a target of the whimsical Taliban soldiers and we are targets for additional reasons. They don’t consider us Muslim,” he says, emphasising that even non-Hazaras are hiding in parks and the woods to escape the Taliban who, according to information he claims to have gathered from friends back home, are ransacking home after home in most cities to either beat up or kill males they consider are enemies and take away their women to marry them off to the Taliban fighters.

The Hazaras are the most persecuted ethnic group in Afghanistan and their marginalisation starts from the time of the Durrani empire in the 18th century. As a result, Hazaras, who were a numerically preponderant community in the region, dwindled over time, as many people fled the country and many more perished in genocides and systematic torture. They were also forced to abandon their vast original homelands in Helmand and elsewhere and flee to other parts of the country. Hazaras, who are Shias, currently account for around 9% of Afghanistan’s 38-39 million people, majority of whom are Sunni. Centuries of oppression at the hands of Pashtun kings and later under Pashtun-dominant governments, Taliban and ISIS meant that many of them had to flee from central Afghanistan to Iran and in recent decades to Pakistan.

Habibullah Mohammadi, a former soldier who is now a baker in Lajpat Nagar, Delhi, had to flee the country in 2018 as the Taliban grew in strength in Helmand where he was posted

Habibullah Mohammadi, a former soldier who is now a baker in Lajpat Nagar, Delhi, had to flee the country in 2018 as the Taliban grew in strength in Helmand where he was postedRecent studies and even works of fiction have brought global attention to the maltreatment and othering of Hazaras. The 2003 literary classic Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseini portrays various aspects of Afghan life and what it is to be a Hazara in a Pashtun-dominated country. Academic projects by the likes of Niamatullah Ibrahimi and Sayed Askar Mousavi have put the spotlight on past pogroms and systemic discrimination against them.

Habibullah Mohammadi is a lanky 24-year-old who was a soldier in the Afghan army that was created with the help of the US forces following the American invasion of 2001, but he had to flee the country in 2018 in the face of growing threat from the Taliban. As a soldier, he was posted in Helmand, the largest province by area of all 34 provinces of Afghanistan that also became the hotbed of insurgent activities ever since 2002. People had started fleeing this province as early as last year when the clashes between the Taliban and the Afghan army heightened.

Mohammadi, who currently works in Delhi’s Lajpat Nagar area as a maker of breads, is now the sole breadwinner for his family back home in Mazar-i-Sharif where his parents live with his two brothers and two sisters. “I speak to them often, but as you know, nobody is happy there because there is too much trouble. Things are very difficult for us Hazaras,” he says, adding, “but what can we do about it? What is the point of worrying?”

These days he is neither able to send money to them through anyone travelling back to Mazar nor are any of the members of the family able to find work. “There is a complete shutdown. My father and mother used to work as tailors, but it was not a good business at all. One of my brothers has fled to Iran, the other two are studying, but all colleges and schools are closed now. Both the sisters cannot work. Life is really tough there.”

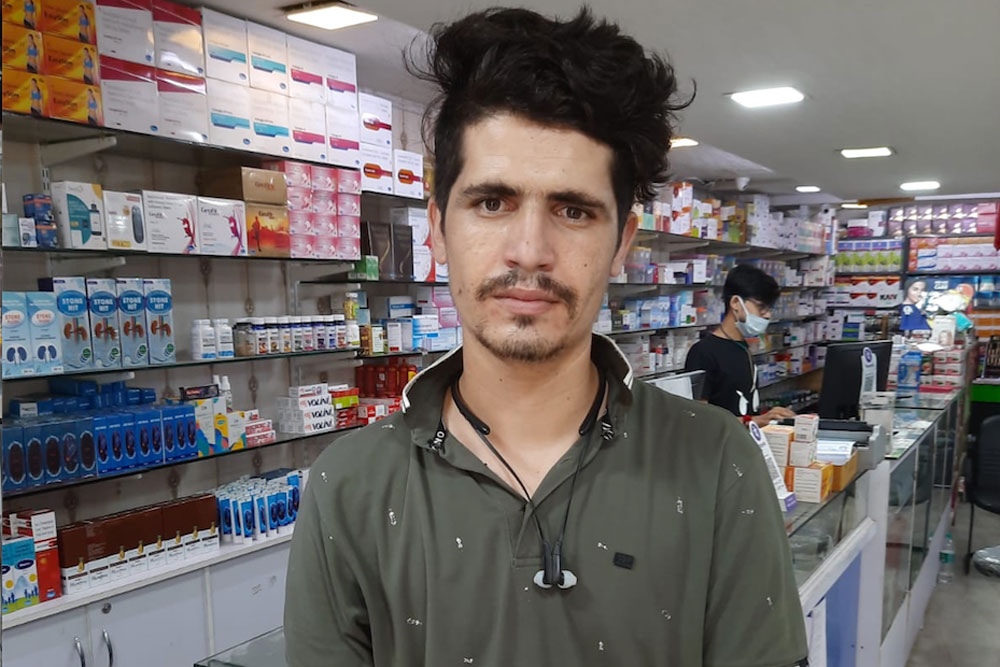

Sahel Hashmi, a Pashtun, says only religious minorities like the Hazaras know the ‘true extent’ of exclusion under the Taliban

Sahel Hashmi, a Pashtun, says only religious minorities like the Hazaras know the ‘true extent’ of exclusion under the Taliban“The question of me going back doesn’t arise at all. First, I am a soldier of the Afghan army, and then I am a Hazara,” he says laughing, as though he is trained to take hardships in life with a sense of wry humour. Mohammadi says he is content with what he earns and gets in India, but hopes that one day UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees) will help him find a home in a western country.

When I speak with Afghani people in Delhi, they laugh at me for not being able to figure out who is a Hazara and who is not. “They are easily identified by their Asian features, I mean Chinese features. Some of them look like us, but most of them are distinguishable by their facial features,” says Sahel Hashmi, who came to India out of economic hardship back home in Kabul where, he says, he and his family live merely two kilometres from the newly constructed Parliament, which was built by India. A Pashtun, the 21-year-old Hashmi who works at a chemist says, “Other ethnic minorities like Tajik, Uzbek and Hazara communities will be able to tell you the real experience of being a citizen of Afghanistan because they are discriminated against. Hazaras are the worst victims of all because they look different and are not considered Muslim by many Sunni clerics.” Rohullah, a Hazara youth, says that they are easy victims in Afghanistan thanks to their looks. They are also despised by Pashtuns here in India because of their religious beliefs.

Rohulla says that the Asian features of the Hazaras, who are hugely discriminated against, make them easily identifiable among Afghans

Rohulla says that the Asian features of the Hazaras, who are hugely discriminated against, make them easily identifiable among AfghansAn ethnic Hazara lady whom I met at her home along with her brother in Lajpat Nagar says they are not very happy with the pace of UNHCR’s work in India. Open had reached out to UNHCR in Delhi and had visited its office in Vasant Vihar for comments over criticism about them being slow in even meeting Afghan nationals, hundreds of whom have congregated outside its office for the past week demanding an audience. The UNHCR office in Geneva also did not reply to mails for clarification. “What we want is safety and opportunity to work so long as we are here in India and for that we need a refugee card, which many of us don’t have. People who travel to Turkey, Greece and other places are able to avail of such benefits and get asylum and later citizenship in western countries at a quick pace,” she says. Hashmi agrees, “Some of these people who are doing a sit-in outside the Vasant Vihar office of UNHCR have been in India for the past 20 years. They need UNHCR to introduce them to countries that are ready to accept them. We have no intention to stay long here in Delhi and take away the jobs of Indians.”

Hazaras, mostly Shias who account for 9% of Afghanistan’s population, are the most persecuted ethnic minority in the landlocked country since the 18th century

Hazaras, who are referred to in Mughal emperor Babar’s accounts titled Babarnama, are considered by some historians to be people of Turko-Mongolian descent and perhaps heirs of Genghis Khan’s armies that had overrun the region in the 13th century. This theory is contested by other historians, saying they are of mixed races from multiple waves of migration.

Hazaras have continuously come under pressure from the ruling classes in Afghanistan. Weeks ago, a statue of Hazara leader Abdul Ali Mazari in Bamiyan was destroyed by the Taliban. In fact, Mazari was executed by the Taliban in 1995. The Taliban had reportedly duped Mazari and his followers into a meeting claiming they had arranged peace talks with a leader of the dreaded outfit. He was then tortured and killed and his body was flung from a helicopter. The Taliban had refuted the charges then, saying he died in an encounter and that he was buried in Mazar-e-Sharif.

“Many of my friends and relatives are stuck there scattered around Afghanistan, but I have no idea what lies ahead of them. Even the Pashtuns aren’t safe there under the Taliban,” former soldier Mohammadi says with an inscrutable smile.

No comments:

Post a Comment