Scott Rosenberg

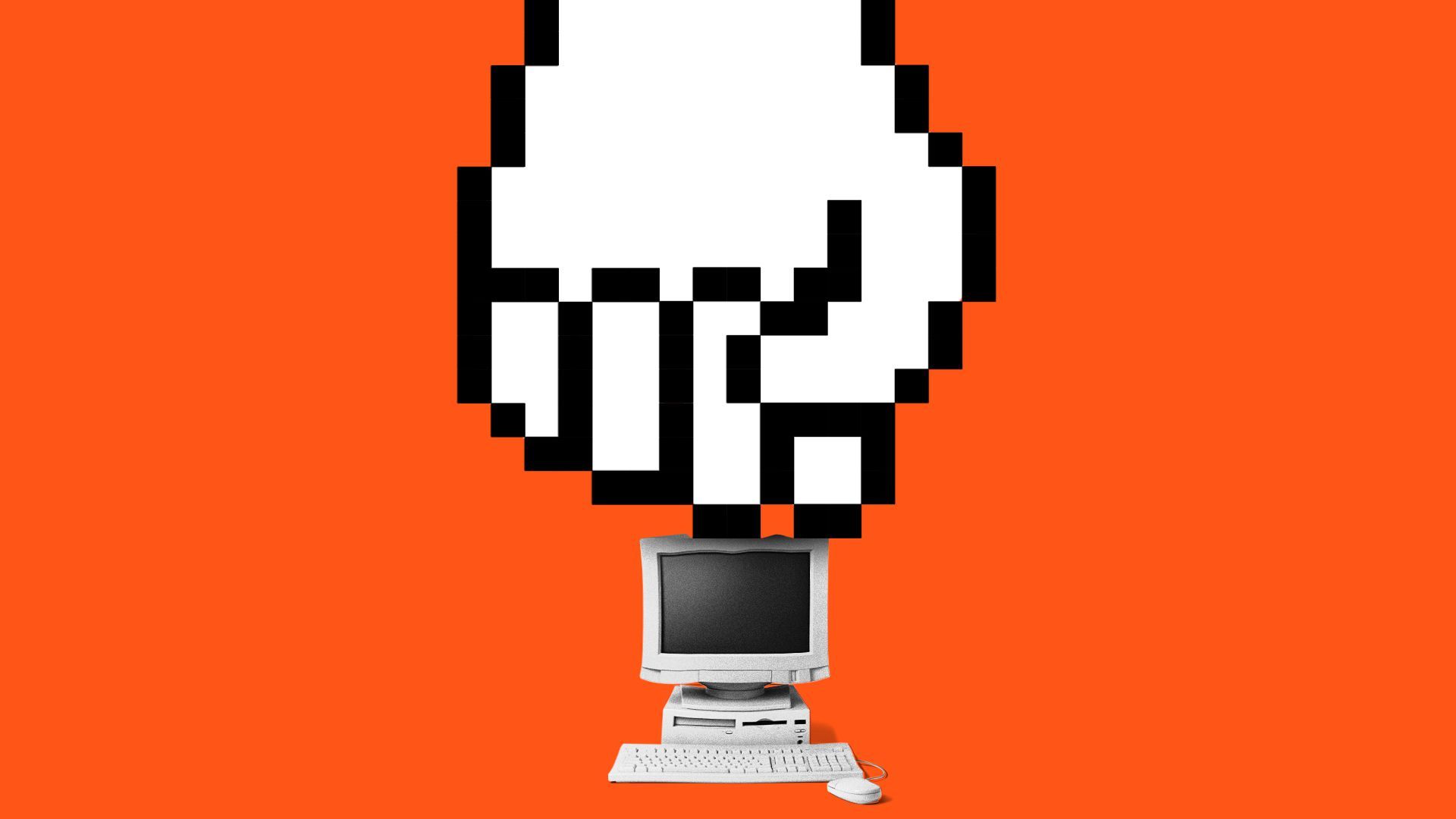

Governments around the world are finding it easier than ever to make the internet, and the companies that run it, knuckle under.

Driving the news: Russia Friday forced Apple and Google to remove an app that supporters of dissident leader Alexei Navalny had created to coordinate opposition votes in Russian elections.

Also last week, China's government removed nearly all online content connected with one of its top movie stars as part of a broader campaign against the power of celebrities, the Wall Street Journal reported.

Full shutdowns of internet access by governments seeking to cut off citizens' access to information for political reasons have become increasingly common, a study Axios reported earlier this month found.

The big picture: Governments are limiting or banning applications, content and connectivity itself — and Big Tech companies, rich and powerful as they are, can't or won't fight back.

From the Arab Spring to the Black Lives Matter protests, the internet has helped organizers build popular movements and even, on occasion, overthrow governments

But for now, at least, the tables have turned, and technology is giving entrenched leaders and parties an effective lever to bolster their power.

In Russia, per a New York Times report, the government of Vladimir Putin threatened specific Apple and Google employees with prosecution if the companies did not act to remove the Navalny app, which the government had said was illegal.

The move came as Russians went to the polls Friday, and followed weeks of government pressure on the companies.

Once the app, which distributed information to opposition voters on how best to deploy their ballots, got blocked, Navalny organizers started using Telegram to spread the word, but by the end of the day that service had taken down their account, too.

In China, actress Zhao Wei's internet presence vanished at the end of August, per the WSJ. Movies featuring the star, who had 86 million fans on Weibo, have disappeared from online services. The government offered no explanation for why she seemed to have fallen out of favor.

The move against Zhao came amid a wider government effort to limit the profile and power of online celebrities and business leaders, including a high-profile take-down of entrepreneur billionaire Jack Ma.

In August China also began removing content seen as criticizing the country's economy.

Around the world, nonprofit Access Now documented 50 internet shutdowns in 21 countries during the first five months of 2021.

Governments in countries including India, Belarus, Turkey, Myanmar and Ethiopia have sought to cut their citizens off from internet access or to ban content and services they don't like.

In the U.S., meanwhile, leaders of both parties have targeted online giants with complaints of censorship and promoting misinformation, amid a broad government effort to constrain the companies' power.

Between the lines: Companies aren't sovereign, so when governments take legal action against them, whatever the motivation, they have little choice but to buckle under or stop operating in a particular nation.

That last option is largely out in China, where most of the U.S.-based internet giants have either been sidelined or chosen to exit, and most online services are provided by domestic firms that can't pick up stakes and leave.

China's model may well become more common as governments seek control — and as the technology powering internet services becomes easier to copy.

Our thought bubble: Organizing our online universe around centralized chokepoints like app stores and search engine monopolies does much of the work in advance for authoritarian governments looking to squelch dissent.

No comments:

Post a Comment