WILLIAM M. ARKIN

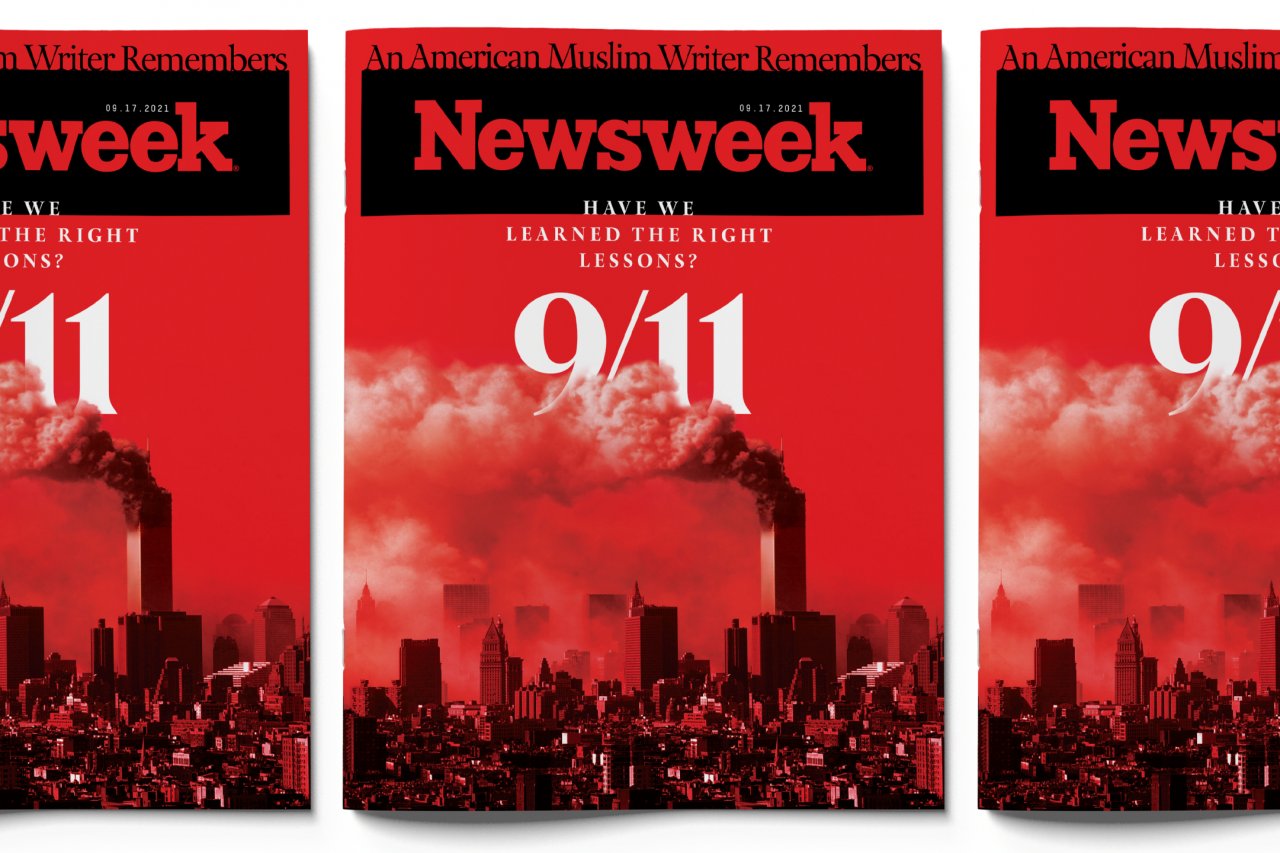

September 11 is the most studied day of our lifetimes. Almost everyone who was old enough remembers the details—where they were, how they felt, what it meant to them. It remains unforgettable.

The U.S. intelligence community had known some sort of terrorist attack was on the way but failed to focus or to act. After 9/11, there was finger-pointing at President George W. Bush and the White House, between the previous Bill Clinton and Bush administrations, at the CIA, NSA, FBI and even at the Pentagon. The government pledged to do better: to break down barriers to intelligence analysis and sharing, and to organize itself so that such a catastrophic event would never happen again.

But even in the immediate aftermath there were more powerful emotions that overshadowed the desire for reform. The desire for revenge propelled the administration of George W. Bush to declare a global war. Panic within the government drove the secret agencies to take their own liberties—through warrantless surveillance, torture and secret prisons, arbitrary watch listing, domestic spying and more. And though reforms did follow, including the largest reorganization of government in 50 years, government performance again faltered. September 11 was followed by other intelligence debacles, from the faulty reports regarding Iraq's weapons of mass destruction to the botched withdrawal from Afghanistan last month: a long line of failures that yearn for accountability.

Polls show that a majority of Americans remain bewildered about the attack, the perpetrators and the reason. And most everyone laments Washington's political and partisan machinations and the decline of American institutions. However, few connect today's national friction to the aftermath of 9/11. Yes, the government has (so far) succeeded in preventing another such attack on U.S. soil, but an even greater disaster in endless war and the collapse of civic life sullies the achievement.

And despite legions of blue ribbon panels to review what happened, despite subsequent revelations of wrongdoing, despite administrations promising to do better, the basic reality of government was exposed: No one is held accountable—not a White House official or top government agency director, not an intelligence analyst or FBI agent, not even a lowly airport security screener.

The cost of government secrecy has also been exposed. It nurtures our world of alternative facts and undermines public faith in government motivations and authority. Secrecy has also fed a generational gap, with young people indifferent to or confused about national security, an entire new generation seeking their own agendas with regard to what is vital for the country and the world.

So yes: We will never forget. But a more interesting question at the 20th anniversary is what we should remember—or more, what should we learn?

Tragic failures

On September 11, 2001, two hijacked commercial airliners crashed into the north and south towers of the World Trade Center. Soon thereafter, the Pentagon was struck by a third hijacked plane. A fourth hijacked plane, bound for the U.S. Capitol building, crashed into a field in Somerset County in southern Pennsylvania after passengers managed to overpower the hijackers. The 19 hijackers were all young Arab men, from four different countries, all sacrificing their lives on behalf of Al-Qaeda.

The attacks that day killed 3,030 U.S. citizens and other nationals. There were 2,735 persons who died in the twin towers in New York: 2,184 at work in the buildings, 129 aboard the two aircraft (119 passengers and crew, and 10 hijackers), 343 firefighters, 71 law enforcement officers, and eight private emergency medical technicians and paramedics. A total of 189 were killed at the Pentagon: 125 uniformed military, civilian and contractor personnel in the building and 64 passengers, crew, and terrorists. Forty-four died in Pennsylvania.

The day itself was horrific in other ways. Despite spending hundreds of billions of dollars on presidential communications, on nationwide air defenses, on airport security and on emergency preparedness, despite preparations that were supposed to work in the face of a full scale nuclear war, hardly any part of what had been created worked.

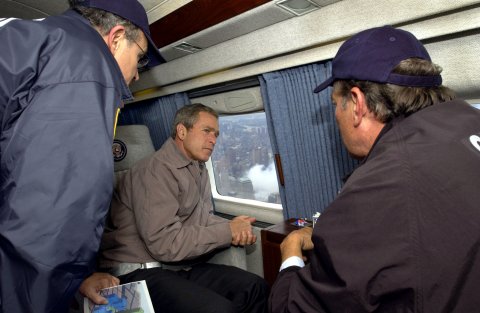

Leaders were preoccupied with the most basic activities—getting phone calls through, finding and protecting their loved ones, keeping up with the news, struggling with the rumor mill. For a large part of the day, President Bush was unable to reliably communicate or know precisely what was going on. Successors to the presidency and Cabinet members ignored continuity-of-government plans and procedures for emergency response. The White House and Pentagon were out of sync and made decisions without any basis in fact. There was stunning confusion regarding what the president ordered Air Force fighter jets to do and why. The Pentagon confusedly declared a high-level alert—including nuclear forces—with key decision makers, including Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld and acting Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Dick Meyers mistaking measures to increase the protection of American forces with an alert that prepared for war.

Hijacked United Airlines flight 175 flies towards the south tower of the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001 in New York City.CNN/GETTY

Many of the organizational and technological deficiencies of 9/11 have since been corrected, we've been told. But in an age where information overload is exponentially worse, and where cyberthreats raise questions about the reliability and credibility of communications and decision-making, there is no particular reason to believe that the very same issues won't repeat in some future crisis. And indeed everything that happened 20 years ago recurred in the past two years. With the emergence of COVID-19, continuity and emergency actions again became important when questions of the president and vice president separating were raised, and yet none of the established procedures were followed. And when rioters swarmed the Capitol on January 6th, the lack of preparedness was alarming. Questions of who was in charge again became paramount. The dots were not connected; the information did not flow; the decision-makers were paralyzed.

The failure to connect the dots, big and small, was certainly a theme of the 9/11 Commission, which published its final report three years after the attacks. It stated that "the 9/11 attacks were a shock, but they should not have come as a surprise. Islamic extremists had given plenty of warnings that they meant to kill Americans indiscriminately and in large numbers." But it's worse than that. As early as 1995, when a plot was foiled in the Philippines, the CIA knew of plans to use airplanes in an attack. And though an August 6th President's Daily Brief (PDB) became infamous as the warning that was ignored, an item in the December 4, 1998 PDB titled "Bin Laden preparing to hijack U.S. aircraft and other attacks" said that the Al-Qaeda leader might "implement plans to hijack U.S. aircraft...and that members of the operational team had evaded security checks during a recent trial run at an unidentified New York airport."

Trained rescue dog Gus and his trainer Ed Apple from the Tennessee Task Force One Search & Rescue team searching for survivors in the wreckage at the Pentagon following 9/11 terrorist attack.MAI/GETTY

Warnings continued over the years and particularly peaked in July 2001, the CIA expecting something spectacular during the summer. There is no question that the Agency had a hard time getting the attention of President Bush and his deputies, but as Newsweek's "Road to 9/11" series attests, even in the last weeks before 9/11, there were abundant signs and warnings that the intelligence community and the FBI themselves failed to follow up on or heed. The Bush administration might not have been paying sufficient attention, but the security agencies flat out failed to do their own jobs.

"Nobody in our government, at least, and I don't think the prior government, could envisage flying airplanes into buildings," stated President George W. Bush. National Security Advisor Condoleezza Rice claimed: "I don't think anybody could have predicted that they would try to use an airplane as a missile, a hijacked airplane as a missile." FBI Director Robert Mueller said: "There were no warning signs that I'm aware of that would indicate this type of operation in the country."

The 9/11 Commission, of course, gave these officials the space to explain, and laid out the details of the many failures that accumulated to forge the attacks. But in its desire to produce a useful and supportive bipartisan document that would suggest practical reform, the Commission also floated above the fray, not pointing fingers and not naming names, keeping the government's secrets and not forcefully condemning anything. In an environment where no one was held accountable or took responsibility, reform became a matter of the American people writing the government a blank check, creating gigantic new bureaucracies but eliminating nothing. And because no one was held accountable, the public was left to wonder if important information was being withheld.

Revenge

Once the attacks in New York and Washington occurred, it was clear that Al-Qaeda, then led by Osama bin Laden, was responsible. Though many, including many in the news media, questioned whether there was "proof " that a man in a cave could be behind such a diabolical plot, once the airline passenger manifests became available, the intelligence agencies were able to see the abundance of information that they already possessed but never analyzed properly—two men had entered the United States in January 2000 and moved to San Diego and then found their way onto the flight that hit the Pentagon; four hijacker pilots attended various flight schools throughout America and had been awarded pilot's licenses by the Federal Aviation Administration; tens of thousands of dollars had moved from the Middle East; three of the four pilots were connected to a Hamburg cell known to German intelligence, Afghanistan was abuzz with chatter and terrorists were on the move expecting retaliation for something.

National Security Advisor Condoleezza Rice listens as President Bush speaks on trade promotion authority at the Department of State.BROOKS KRAFT/CORBIS/GETTY

On September 14, the Senate and House passed resolutions granting President Bush the power "to deter and preempt any future acts of terrorism or aggression against the United States." A sole single member of Congress—Barbara Lee of California—voted no, fearing that the resolution was too vague, that it constituted a blank check.

Though there was broad support for military action against Al-Qaeda in Afghanistan, the Pentagon was wary of getting bogged down in what is often called the "graveyard of empires." It therefore chose a combination of airpower and small contingents of special operations forces to pursue Al-Qaeda, keeping the U.S. footprint to a minimum but also following a strategy of seeking to minimize the risks to American armed forces. That risk aversion meant that by the time the bombing began on October 7th, there was nothing angry in the retaliation, and annihilation, while voiced, was never pursued in the war plans. Still, over two months, the Taliban regime was toppled and Al-Qaeda scattered. But by then, public interest was already waning and the military high command decided to deploy ground forces to pursue the many jihadists who survived.

It was the first of many military missteps—the belief that conventional forces were needed or that the task would be easy. Osama bin Laden slipped away across the Pakistani frontier and American forces stalled into conflict more akin to a perpetual traffic jam, the occupation of the country slowly accumulating to become America's longest war.

US President George W. Bush tours the World Trade Center disaster site aboard his helicopter Marine One September 14, 2001 with New York Mayor Rudolph Giuliani (L) and New York Governor George Pataki (R).ERIC DRAPER/WHITE HOUSE/GETTY

President Bush had pledged to eradicate Al-Qaeda but the administration was eager to move the war machine from Afghanistan to Iraq. The animus regarding Iraq, predating 9/11, created giant new smoke screens and self-deceptions. Though Al-Qaeda had already demonstrated in August 1998 in its simultaneous attacks on two African embassies that it had the capability to carry out large scale strikes, many of the Cold War veterans of the Bush administration believed that a nation state had to be behind the attacks. Thus the administration entertained every allegation of an Iraqi connection to 9/11.

And why? Because the truth of 9/11 was still too difficult to acknowledge. Osama bin Laden had laid out a worldview over the years, one that centered on opposition to the U.S. military presence in the Middle East. Starting in 1990 after the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait, he said that the presence of Christians and Jews in Saudi Arabia was humiliating to the heart of Islam. He wrote open letters to the Saudi king asking how it was that a country that spent more per capita on defense than any other, and had purchased the best arms money could buy, couldn't defend itself. When U.S. forces never left, bin Laden took up the banner of "a million" Iraqi children who he said were being killed in a genocidal campaign of sanctions and bombing. He similarly decried Israeli attacks on Lebanon and on Palestinians. Islam was under attack from all directions, he said, and the Islamic world was being threatened by globalization.

Policemen and firemen run away from the huge dust cloud caused as the World Trade Center's Tower One collapses after terrorists crashed two hijacked planes into the twin towers, September 11, 2001 in New York City.JOSE JIMENEZ//GETTY

None of this is to excuse the acts of terrorism, but Osama bin Laden voiced grievances that appealed to a much broader group of Muslims than anyone was willing to admit. But America was in no mood for introspection. To examine U.S. policy in the Middle East that might have fueled the attacks became un-American. To suggest that Saudi Arabia, in promoting fundamentalist Islam and in supporting bin Laden, might have been partially responsible for 9/11, was a geopolitical no-no.

Though the Iraq-9/11 connection deflated, the administration then put together every scrap they could find to prove that Saddam Hussein was continuing to develop (and even possessed) nuclear, biological and chemical weapons. "There is no doubt in my mind," Secretary of State Colin Powell told the United Nations and the world in February 2003. Like conspiracy hunters after 9/11 "truth," the Bush administration latched on to whatever confirmed their biases and ignored anything that questioned their presumptions. And the intelligence community failed to properly analyze the situation regarding Iraqi WMD, and then failed to forecast what would happen in Iraq once Saddam was gone.

George W. Bush said that "we'll fight them over there so that we don't have to fight them here." And to some degree, he was right; that has been the main achievement in two decades of war. A combination of relentless pursuit of terrorists, the counterterrorism focus, and the transformation of American domestic life did thwart another 9/11. Now, the Biden administration is taking several steps toward finally closing the 9/11 chapter, in the withdrawal from Afghanistan, in pledging to get the U.S. military out of Iraq, and in ordering a global "posture review" of U.S. military deployments. There is a move afoot in Congress to repeal the blanket authorizations behind the War on Terror.

"We went to Afghanistan because of a horrific attack that happened 20 years ago," Joe Biden said when he announced the withdrawal. "That cannot explain why we should remain there in 2021."

Nor does the unfinished business of eradicating Al-Qaeda or the return of the Taliban explain the decision to withdraw. The truth is that official Washington—and the Pentagon—has just grown exhausted with the fighting. And despite all the flag waving, the public is no longer supportive of the war effort. No one believes any longer that the United States—and certainly not the U.S. military—can bring democracy and stability to the countries where we've fought. The COVID pandemic, the divide at home, China and Russia, climate change and other geopolitical challenges have overtaken the threat of international terrorism.

There has always been a strong voice in America that has argued that the best way to honor the losses of 9/11 is not just by pledging that it never happens again, but to also pledge that the young men and women sent out there on the never-forget crusade were adequately equipped, both materially and endowed with a clear mission, all so they could be safely brought home.

Rescue workers sift through the wreckage of the World Trade Center September 13, 2001 in New York City, two days after two hijacked airplanes slammed into the twin towers, levelling them in an alleged terrorist attack.MARIO TAMA/GETTY

The war is indeed over now—officially. But the U.S. military is not completely withdrawing, and it will continue to fight in these countries (and others) from "friendly" bases in countries like Kuwait and the Gulf States, resorting even more to remote warfare, relying on airplanes and drones, our generation's weapons and the very ones that the terrorist chose to use to teach us a lesson about vulnerability and power.

Could it happen again?

Twenty years after 9/11, al Qaeda central is mostly neutered, its charismatic leader dead and with no one equivalent to take his place. Of course we don't know what we don't know. But plotting on the scale of a 9/11 is ever more difficult, with the clandestine war against terrorists continuing, with a national counterterrorism effort bureaucratically focused on the matter, and airport security now institutionalized. And there is no question, at least in the short term, that the ongoing pandemic has slowed down everything, including international terrorists, making travel more difficult and largely closing off the United States, thereby increasing safety against external threats.

But Al-Qaeda isn't eliminated, and there are other affiliates like the Islamic State, Al-Qaeda's affiliate in Yemen, Boko Haram in West Africa and al-Shabaab in East Africa, to name a few, that continue to flourish. And there is a long list of terrorist plots and attacks—the shoe bomber, the underwear bomber, the Boston marathon, AQAP's threats to commercial aviation, trucks plowing into crowds in New York City and elsewhere—that suggest that while we may have prevented another 9/11 type attack, we may have just transitioned from the spectacular era to the mundane.

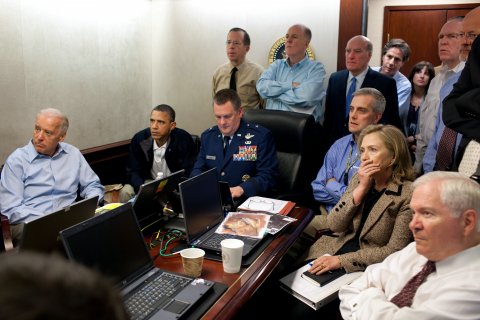

President Barack Obama, Vice President Joe Biden, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and members of the national security team receive an update on the mission against Osama bin Laden in the Situation Room of the White House May 1, 2011 in Washington, DC.PETE SOUZA/THE WHITE HOUSE/GETTY

As the Biden administration makes its grand gestures, and as the national security establishment officially shifts from the War on Terror to "great power competition," there are other dangers ahead. In our zeal to withdraw troops from Afghanistan, we ignore ISIS-Khorasan, a terrorist organization that is seizing the Al-Qaeda mantle and has shown its propensity for suicide attacks. As the intelligence community shifts its attention, it applies fewer resources to the terrorism problem set. New global challenges beyond COVID, such as climate change, increasingly seize the attention of the national security community. And the Department of Homeland Security, created to have a singular focus on terrorism, has grown into a giant bureaucracy that is more and more diffuse—immigration policy, cyber security, critical infrastructure protection, even the sanctity of the elections. And many of the terror hunters themselves are now focused on domestic unrest and extremism, drawing resources from international operations.

The 9/11 Commission ultimately concluded that while there were many mistakes and abundant organizational limitations that made the attacks possible, the disaster also was caused by failures of imagination. One of the still unexplored options for the future, beyond the airpower and special operations American way of war, is that war just might not be the right paradigm. After 9/11, anyone who rejected military action and argued that terrorism was a law enforcement matter was shouted down. And yet today, the military effort looks more and more like law enforcement, as fighters seek out individual perpetrators and go after the equivalent of crime families, judge, jury and executioners targeting enemies before crimes have even been committed. This is not a viable strategy that addresses the resilience of terrorism, but other approaches of either kinder wars or reeducation also ignore the fact that the U.S. still occupies the Middle East, stimuli for propelling more to seek out the very thing we hope to eradicate.

People walk through the Empty Sky 9/11 memorial in Liberty State Park on February 27, 2018 in Jersey City, New Jersey.GARY HERSHORN/GETTY

Twenty years after Pearl Harbor, the commemorations included ceremonies to remember the tragedy and subsequent war. But America had moved on to its greatest period of prosperity and growth. Germany and Japan had been made over into democracies, and though the nuclear arms race dogged society, even that shadow was beginning to dissipate in recognition that the planet was vulnerable. To put it mildly, it's hard to see anything equivalent emerging from the heartbreak of 9/11. Ultimately, that is its greatest tragedy.

No comments:

Post a Comment