On a warm June evening in downtown Manhattan, tourists hoping to visit the National September 11 Memorial & Museum are disappointed. The spot is closed after 5 p.m., a security guard repeats patiently to visitors. From behind a rope, the tourists look at the spaces where the Twin Towers used to be. The names of the 2,977 people killed by Al Qaeda in September 2001 are etched into bronze parapets surrounding two pools. Water flows down 30 feet in clear streams over the walls into the pools. During the day, if you are close enough to the water, the endless noise of the city is drowned out. But on nights like this one, New York’s cacophony makes itself heard here. If you close your eyes, it doesn’t sound very different than it did before the terrorists devastated the buildings.

This September marks the twentieth anniversary of the attacks. “Everybody was traumatized,” remembered Richard Clarke, the chief counterterrorism adviser at the time. In the immediate aftermath, Clarke said, the Bush administration was mainly concerned with reacting swiftly to prevent another attack. “[We were trying] to put ourselves in the heads of Al Qaeda, imagine what they might do next, and that was difficult because there were so many vulnerabilities, particularly back then, and a very long list of things they could do.”

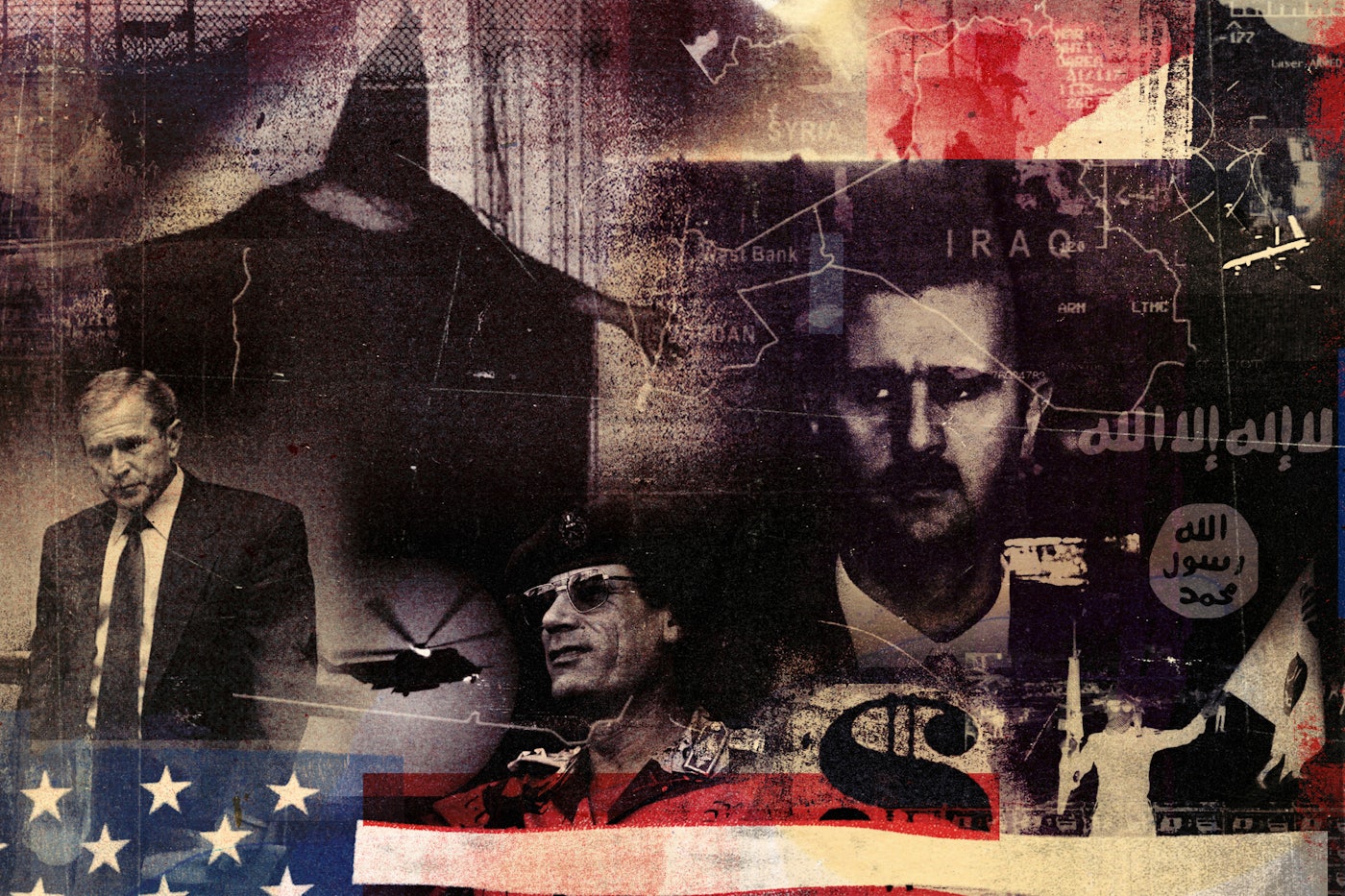

Perhaps inevitably, fear and anger influenced U.S. policymaking in the weeks and months after the attacks. But so did other tendencies with deeper sources in Washington foreign policy establishment circles: delusions of grandeur, threat inflation, faith in the ability of armed force to solve political problems, and a refusal to accept limits and trade-offs. As President George W. Bush’s fatefully termed “Global War on Terror” enters its third decade, its enormous costs proliferate.

The price tag is staggering. More than 7,000 American military personnel have died in the U.S.-led wars worldwide since 9/11, and as of 2015, another 50,000-plus had been wounded. An additional 30,000 active-duty personnel and veterans of these wars have died by suicide. More than 7,402 U.S. contractors were also killed, in Afghanistan and Iraq alone. The direct deaths in the wars were upward of 800,000, but Brown University’s Costs of War project, which supplied the data in this paragraph, found that several times that were killed indirectly through such causes as war-related disease and water shortages. As of last year, the wars have cost about $6.4 trillion, and there will be the future costs of service members’ long-lasting benefits. And finally, the wars have created at least 37 million refugees.

In addition, civil liberties have been curtailed, innocent Muslims have been entrapped and targeted, and the constant drumbeat about defeating Islamists abroad has fueled rampant Islamophobia and white nationalism at home. “The anti-Muslim discourse that arose in the wake of 9/11 was a vector through which open racism and open bigotry was smuggled back into the mainstream of American politics,” said Matt Duss, Bernie Sanders’s foreign policy adviser. Broad, hateful generalizations about Muslims and Islam became permissible because of the trauma of the attacks. “I think it normalized these sorts of claims about different groups of people, immigrants, Latinos, Asians, Black people, or others,” Duss said. Donald Trump exploited that bigotry in his 2016 election campaign.

The United States has been successful in some areas. Most notably, foreign terrorists have not attacked American soil en masse since 9/11. “It’s simply harder for foreign jihadists to attack the United States at this stage,” said Steven Simon, who worked on Middle East affairs at the National Security Council (NSC) during the Clinton and Obama administrations. Clarke said that increased funding for technology, the proliferation of surveillance cameras, and the development of facial recognition technology have reduced American vulnerabilities. Simon agreed, saying, “Ranging from the creation of the Homeland Security Department to much tighter defenses along borders, it’s harder to get into the country.” Cooperation between intelligence agencies and law enforcement is far better than it was.

In addition, Al Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden was killed in 2011, and 9/11 mastermind Khalid Sheikh Mohammed was captured in 2003. Military strikes and raids have eliminated many other jihadis, notably Islamic State leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. ISIS is fragile today. And, finally, Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein was captured.

Even those successes are complicated, however. Hussein’s overthrow created the opening for what became ISIS. Mohammed was tortured repeatedly, and he still awaits trial at Guantánamo Bay, along with 39 other detainees, underscoring America’s inability to counter the terrorist threat while adhering to the rule of law. And while jihadis have not attacked American soil en masse in the past two decades, this could have been achieved at significantly lower costs, by relying mostly on defensive measures after ousting the Taliban and wounding Al Qaeda in late 2001.

There is no consensus on why the United States has remained free of major terrorist attacks for the past two decades. “We do not know why there has been no mass casualty attack in the United States like the 9/11 assault,” said Simon. “We do know that Al Qaeda got very lucky in 2001. We do not know whether there was a workable Plan B. We know that there were many Al Qaeda operatives worldwide when we started to look for them, but we do not know if they were prepared to sustain a campaign against the U.S. homeland.”

Bush had alternatives. He could have targeted Al Qaeda exclusively and explained that terrorism should be dealt with by mostly nonmilitary means. He could have counseled Americans to be resilient and avoid overreacting even as news programs endlessly repeated clips of the planes hitting the towers. “We, the United States, missed an off-ramp which could have been taken a few weeks—at most, a few months—after the initial [Afghanistan] intervention in the fall of 2001,” said Paul Pillar, then the CIA’s national intelligence officer for the Near East and South Asia.

There was enormous global solidarity with the United States after the attacks, and there was a way to build on that, Duss said. Leaders could have emphasized the shared vulnerability countries have to transnational jihadis and worked with the international community to both contain terrorism and address its root causes. “The Bush administration made a rhetorical head fake in that direction, but the policy of endless global war spoke for itself,” he said.

There are not only retrospective assertions. Astute critics offered these prescriptions contemporaneously. “Massive military force is not a winning weapon against these enemies. It makes the problem worse,” the political scientist John Mearsheimer wrote in The New York Times in November 2001, arguing against the United States sending American troops to Afghanistan. He advocated a patient strategy oriented around “clever diplomacy, intelligence-gathering, and carefully selected military strikes.”

Michael Howard, the eminent British historian, argued that the Bush administration’s war framework would have disastrous implications. “To declare that one is at war is immediately to create a war psychosis,” he said in London in late 2001. “It arouses an immediate expectation, and demand, for spectacular military action against some easily identifiable adversary, preferably a hostile state—action leading to decisive results.” Instead, Howard recommended a policing project—ideally led by the United Nations and international courts, although he had no illusions about that happening—that isolated terrorists rather than elevated their importance.

Instead, the foreign policy establishment almost universally saw 9/11 as a call to arms equivalent to a world war. Intellectuals needed to play a major role. The Weekly Standard, the journalistic home of neoconservatism that would shape the Bush team’s thinking, said, “We have been called out of trivial concerns,” adding, “We live, for the first time since World War II, with a horizon once again.” Christopher Hitchens seemed to speak for many when he declared that, in addition to nausea and anger, he felt “exhilaration” at the attacks. “I realized that if the battle went on until the last day of my life, I would never get bored in prosecuting it to the utmost,” he wrote.

Indeed, while the war on terrorism has devastated countries and killed scores of people, it hasn’t been boring. Unfortunately, it isn’t completed, either. The war on terrorism is now entering its fourth phase. The first and most impactful phase was the Hegemonic: an attempt to use armed force to end challenges to American predominance. The second phase was Internationalist, as first Bush rhetorically and then Barack Obama in practice tried to wage a campaign that balanced democracy promotion, multilateralism, and signature strikes as a counterterrorism strategy. Donald Trump marked the Jacksonian phase, defined by a combination of Islamophobia, nativism, and sporadic uses of force. President Joe Biden looks to be beginning a Moderate Internationalist phase, reflecting some of the limits imposed on the United States after two decades at war.

Our many failures these past 20 years have not led to a widespread rethinking of America’s foreign policy assumptions. And what’s worse, the toll that the war on terrorism continues to take on American power, prestige, and domestic cohesion makes it significantly harder to compete with China.

The good news is that the foreign policy establishment has learned some lessons. In particular, there seems to be a moratorium on trying to build a functioning state elsewhere, particularly in the Middle East. “Most in the foreign policy community would oppose another conflict of choice in the Middle East,” Biden national security adviser Jake Sullivan wrote in 2018. If another large terrorist attack occurred, “I am not so confident that we would try a massive state-building effort to build a new government,” said the Brookings Institution’s Michael O’Hanlon, who was an important supporter of the Iraq War in real time.

But as Sullivan’s and O’Hanlon’s remarks imply, even skepticism of state-building is tenuous. Our many failures these past 20 years have not led to a widespread rethinking of U.S. foreign policy assumptions. And what’s worse, the toll that the war on terrorism continues to take on American power, prestige, and domestic cohesion makes it significantly harder to compete with China, which appears to be a more vexing and important problem than terrorism ever was.

The PreHistory of the Post-9/11 Era

The sources of America’s post-9/11 conduct date to at least the closing years of the Cold War, when the United States found itself devoid of both an enemy and a strategy. The national security state was constructed after World War II to counter the Soviet Union, so the demise of that empire should have led lawmakers to rethink U.S. foreign policy radically. There was much talk in those days of the “peace dividend” that would help solve domestic ills.

Well ... maybe it was inertia. Or maybe states simply cannot limit themselves. Whatever it was, officials declined a scaled-down global role. Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Colin Powell joked in 1991, “I’m running out of demons, I’m running out of villains.” Instead of reducing capabilities and ambitions commensurate with an unprecedentedly secure environment, Powell approved a strategy that envisioned enlarging U.S. ambitions.

Two Pentagon staffers—I. Lewis “Scooter” Libby and Zalmay Khalilzad, who were influential after 9/11—helped draft a 1992 strategy report for Powell, Defense Undersecretary Paul Wolfowitz, and Defense Secretary Dick Cheney, who all signed off on it. “Our first objective is to prevent the reemergence of a new rival,” the policy statement read. Not to protect Americans or secure the republic, but to maintain the country’s supremacy. According to the strategy, the United States needed to “dete[r] competitors from even aspiring to a larger regional or global role” and to use military action unilaterally and preemptively to enforce those aims.

The report and its endorsement of preemptive force were hugely controversial. Presidential hopeful Bill Clinton’s deputy campaign manager charged that the Pentagon was yet again “find[ing] an excuse for big budgets instead of downsizing.” Delaware Senator Biden said that the Defense Department was pursuing “a global security system where threats to stability are suppressed or destroyed by U.S. military power.” Instead, he recommended that the United States pursue “the next big advance in civilization”—“collective power through the United Nations.”

Once Clinton took office, talk of domination receded. The Arkansas governor was less interested in foreign policy than his predecessors had been and had come of age as a post-Vietnam Democrat, cognizant of the limits of U.S. power. Defense budgets were slashed. But as the years passed, Clinton comfortably used military power (in Somalia, Haiti, the Balkans, and Iraq), circumvented the United Nations when needed, and expanded NATO eastward with little regard for Russian sensibilities. “The possibilities seemed endless, in the 1990s, for the ways in which America could reshape the world,” said James Goldgeier, who served on Clinton’s National Security Council. Charles Kupchan, a political scientist who also served on both Clinton’s and Obama’s NSCs, said that “the roots of Trump’s ‘America First’ start sinking into the ground in the 1990s, when the Cold War came to an end, and a sense of triumphalism” emerged.

Clinton was pushed by the coalition of hawks that coalesced around groups like the Project for a New American Century (PNAC), founded in 1997. PNAC connected liberal internationalists with Cheney, Wolfowitz, and other neoconservatives and assertive nationalists advocating a more aggressive foreign policy. “If you go back and look at all the signatories for all the letters, there’s probably an equal number of Democrats that were signatories to various projects,” said Gary Schmitt, PNAC’s executive director in the years it was active. In 1998, the group wrote an open letter calling for regime change in Iraq. When Bush II became president, 10 signatories to PNAC’s various letters joined the administration.

At first, Bush was more reticent to use force than some PNAC types wished. He avoided confrontation with China, for instance, and criticized state-building. When Al Qaeda attacked on 9/11, however, that calculus changed.

Phase One: Hegemony

Hours after the planes hit the Twin Towers, Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld strategized. Rumsfeld had signed a PNAC statement urging the Clinton administration to “challenge regimes hostile to our interests and values[,] ... shape circumstances before crises emerge, and to meet threats before they become dire.” Now, an aide noted Rumsfeld’s post-attack requests for intel in a series of notes: “Judge whether good enough [to] hit S.H. [Saddam Hussein] @ same time. Not only UBL [Osama bin Laden].” “Hard to get good case.” “Go massive. Sweep it all up. Things related and not.”

Rumsfeld’s thinking defined the administration’s approach to exploit the emergency to accomplish extravagant ambitions. Bush needed a strategy to combat terrorism, and his advisers provided him with some of the ideas first outlined in the 1992 strategy report and by PNAC. “They had to be forward-leaning in a lot of different ways on the national security front than they had thought they were going to have to do when they first came into office,” said Schmitt.

Leading Democratic politicians quickly assented to Bush’s binary rhetoric. “Every nation has to be either with us, or against us,” New York Senator Hillary Clinton said. “Everyone has to support our president.” In joining nearly all other senators in voting for the illiberal USA PATRIOT Act, Biden, then the chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, repeatedly observed that he’d anticipated the law with his 1995 anti-terrorism legislation. “The bill [Bush’s Attorney General] John Ashcroft sent up was my bill,” he complained. When in 2002 Bill Clinton urged the Democrats to strengthen their stance on national security, he revealed the cynical reasoning behind his party’s full-throated support for the war on terrorism: “When people are insecure, they’d rather have someone who is strong and wrong than somebody who’s weak and right.”

The swift deposing of the Taliban appeared to vindicate Bush. But then the administration pursued a maximal ambition—building a functional liberal democratic state in Afghanistan—without much debate. “I don’t remember anyone’s seriously laying out a goal of occupying all of Afghanistan, staying there, stabilizing it, and reforming it, trying to establish a Western style of government there,” said Clarke. “We seemed to stumble into that without looking at alternatives.” Even worse, Rumsfeld under-resourced the war in Afghanistan, convinced that the United States should use a light footprint. He then pivoted to Iraq.

As the Bush team campaigned to dethrone Hussein and possibly others in the “Axis of Evil,” dissenters within the establishment appeared. Massachusetts’s Ted Kennedy joined Wisconsin’s Russ Feingold and 21 other senators and 133 House members to vote against authorizing Bush to use force against Iraq. Former national security advisers Zbigniew Brzezinski and Brent Scowcroft warned that the Bush administration was acting recklessly and isolating the United States as it geared up for war against Iraq.

But the critics were relatively few in number and weak in influence. Mainstream media outlets—and, quite infamously at the time, this magazine—amplified the administration’s hyperbolic or outright fantastical claims about Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction and links to Al Qaeda. From late 2001 to 2003, reporter Judith Miller printed numerous front-page New York Times stories hyping Hussein’s nuclear, chemical, and biological capabilities, information derived from disreputable exiles and manipulated intelligence.

But she was not alone. Years later, in the journal Democracy, Council on Foreign Relations president emeritus Leslie Gelb analyzed the elite press’s war coverage. He found that only rarely did top news outlets “provide the necessary alternative information to Administration claims, ask the needed questions about Administration policy, or present insightful analysis about Iraq itself.” Gelb confessed why he had supported the war. He admitted, “My initial support for the war was symptomatic of unfortunate tendencies within the foreign policy community, namely the disposition and incentives to support wars to retain political and professional credibility.”

Those dispositions and incentives remain. If another attack occurred, “there certainly would be a lot of pressure to overthrow the offending government,” said O’Hanlon. That pressure exists not just on policymakers but on the media and think tanks that want to have influence. As long as the United States has a massive military at its disposal and a predominant international position, using force to solve geopolitical problems will be difficult to resist. That has been true since the Cold War’s end. “What’s the point of having this superb military you’re always talking about if we can’t use it?” Clinton’s future Secretary of State Madeleine Albright famously asked Colin Powell in 1993. A cataclysmic event like 9/11 temporarily removes the safeguards of public opinion and allows members of the foreign policy establishment to be ambitious in shaping the world through U.S. power.

Phase Two: Internationalism

When military intervention proves disastrous—as the Iraq War did within months—public opinion drifts again. That creates opportunities for new approaches. Bush shifted from his macho threatening posture to one focused on freedom, democracy, and “the ultimate goal of ending tyranny in our world,” as his second inaugural address declared. But the war destroyed his credibility. Barack Obama offered an alternative. As a presidential candidate, he declared his opposition to not just the Iraq adventure but other features of the post-9/11 security state. “I don’t want to just end the war,” he said. “I want to end the mindset that got us into war in the first place.” In his first days in office, Obama issued an executive order banning torture. It was an important decision, ending one of America’s most glaring human rights violations of the twenty-first century.

However, the president declined to officially examine the formation and execution of Bush’s torture policies, let alone hold anyone accountable for them, saying the country needed to look forward rather than backward. Obama’s commitment to undoing his predecessor’s policies was half-hearted in other ways. The day after he outlawed torture, Obama launched two drone strikes in Pakistan that killed as many as 20 civilians. They were the first of 542 such strikes he would approve during his two terms, in lands from Pakistan to Somalia. According to the Council on Foreign Relations, those attacks killed 3,797 people, including 324 civilians.

A U.S. Marine was trapped in a building in Fallujah, Iraq, during fighting in November 2004.MARCO DI LAURO/GETTY

Some were undoubtedly terrorist leaders, and their elimination is welcome. But recent scholarship suggests that “drone strikes that kill terrorist leaders may ultimately lead to more, not fewer, terrorist attacks,” the political scientist Anouk Rigterink wrote in Foreign Affairs. That’s because lower-level terrorists can be even more reckless and violent than their leaders, and fragmented terrorist groups are harder to monitor. Rigterink noted that, while drones killed plenty of terrorist leaders in Pakistan between 2004 and 2015, the groups they led committed five times as many attacks in 2015 as they had 11 years earlier. That’s to say nothing of the civilian casualties signature strikes cause.

The strategic logic of drone strikes is at least arguable. Less defensible was Obama’s agreement in 2009 to add 30,000 troops in Afghanistan. It was clear that the war was unwinnable. Obama reportedly felt pressured by the military to support the surge in Afghanistan despite its evident fruitlessness. “Obama, he had some difficulty, because of the position that Democratic presidents often find themselves in, had some difficulty putting forward that proposition, that policy, and so he didn’t,” said Jeremy Shapiro, a former State Department hand who worked with General Stanley McChrystal’s team to develop a new strategy for Afghanistan in 2009.

But Obama also offered a Democratic Party alternative to the GOP’s Hegemonic conception of foreign policy, pushing liberal internationalism as the approach that best defends the United States from terrorism, sustains global acceptance, and protects vulnerable people elsewhere. The ill-fated Libyan intervention was part of that.

It was a well-meaning attempt to avert a massacre of rebels and civilians by leader Muammar Qaddafi, whose son had warned that “rivers of blood” would soon run in Libya. But in addition to exceeding the United Nations mandate to protect civilians, the coalition that invaded the country left behind a failed state marked by jihadis and grievous human rights abuses. Democrats were initially triumphalists in the wake of Qaddafi’s ouster. In 2012, Ivo Daalder, then the U.S. ambassador to NATO, co-wrote an article in Foreign Affairs saying: “By any measure, NATO succeeded in Libya.” This was the liberal version of Bush’s “Mission Accomplished” moment. Daalder, who still believes the initial intervention was justified, concedes now, “I learned from that that it’s hell of a lot easier to start a war than to end it.”

The disaster in Libya—coupled with ongoing failures in Iran and Afghanistan—had spillover effects, rightly convincing Obama that invading foreign countries often backfired. The CIA trained and armed Syrian opposition fighters, but the program was small-scale. After recklessly warning in 2011 that Syria’s President Bashar Al Assad had to step down and later that he would cross a “red line” by using chemical weapons against civilians, Obama learned that Assad’s military had used sarin gas against rebels and civilians. The president nonetheless called off a military strike against the regime. Some liberals—including his close aide, Ben Rhodes—lamented the administration’s Libya policies.

More than 500,000 people have been killed or have disappeared during the Syrian civil war. However, the tragic reality is that the likelihood of the United States being able to secure a good outcome in Syria—while concurrently losing wars elsewhere—was minimal.

More than 500,000 people have been killed or have disappeared during the Syrian civil war. However, the tragic reality is that the likelihood of the United States being able to secure a good outcome in Syria—while concurrently losing wars elsewhere—was minimal. “The interagency players were conscious of and haunted by the Iraq debacle and to a lesser degree the Afghanistan and Libya interventions,” said Jonathan Stevenson, NSC director for political-military affairs, Middle East and North Africa, from 2011 to 2013. U.S. officials knew that Iran felt Syria was of nearly existential importance to it, and that Hezbollah could save the regime at Iran’s behest. Said Stevenson: “This factor further dampened any taste for even a covert proxy war over Syria with Iran: Its stakes, ergo its motivations and its staying power, were much greater than ours.” He added that, by 2013, ISIS was emerging as the strongest and most effective anti-regime force, which meant that any weapons supplied to the rebels by outside parties—including the United States—could end up in the hands of anti-American jihadis. And indeed, some of those CIA-supplied weapons did find their way to at least one large Al Qaeda–affiliated group. Finally, the opposition groups in Syria were deeply fractured and supported by outsiders. “The mentality of the first decade of the new century, that the Americans can fix things, that really needs to be reexamined,” said Robert Ford, the ambassador to Syria from 2011 to 2012, and the envoy to the moderate Syrian opposition until 2014. He was pulled out of Damascus as the civil war intensified. “We end up going into a place like Syria, or Iraq, places I’ve worked, and we don’t understand them very well, and we don’t understand the history, and we’re not very good dealing with the culture. And we just kind of bumble along, embarrassing our friends, and physically walking into traps exploited by our foes.”

Obama had undeniable successes. The daring May 2011 raid that ended with bin Laden’s death was brilliantly executed. It was a significant blow to Al Qaeda and marked a symbolic victory against Salafi jihadism more generally. The Iran nuclear deal was the most significant diplomatic achievement since the United States helped reunify Germany. The opening to Cuba and the Paris agreement over climate change were similarly wise maneuvers. Obama’s popularity enhanced world opinion of the United States. The Pew Research Center found that America’s favorable rating essentially doubled in some places after Obama was elected and remained positive throughout his two terms.

And yet Obama was unable to undo the mindset that got the United States into Iraq, alas. The urge to intervene in places of peripheral concern to U.S. interests, to overreact to threats, to overutilize military force in dealing with terrorists and others—these outlasted Obama. He was, however, able to revive multilateralism, diplomacy, and the country’s soft power, as well as demonstrate that the United States could track down terrorists anywhere. It was “during this period that the U.S. developed, I think, a phenomenal killing machine,” said Steven Simon. Perhaps too phenomenal.

Phrase Three: Jacksonian

After 9/11, Islamophobic sentiments coursed through the country. Years later, Donald Trump mainstreamed it. Stoking panic about ISIS and Muslims, he exploited the public’s exhaustion after three failed wars. By combining anti-Islamic hysteria, nativism, and belligerency abroad, he resurrected a foreign policy tradition that Bush had flirted with, identified by the political scientist Walter Russell Mead as Jacksonianism. Like their namesake, President Andrew Jackson, Jacksonians are “skeptical about the United States’ policy of global engagement and liberal order building,” but “when an enemy attacks, Jacksonians spring to the country’s defense” with overwhelming force, as Mead wrote.

Severing important institutional ties with the world, Trump undid Obama’s accomplishments, unilaterally withdrawing from the Iran deal and the Paris agreement and ending the rapprochement with Cuba. More generally, he immolated the country’s reputation. “If you look at America’s soft power—defined as the ability to get what you want through attraction rather than coercion or payment—in 2017, American soft power starts a precipitous decline,” said Joseph Nye, a Harvard professor who served in the Defense Department during the Clinton administration. Rather than just an idealistic notion of international harmony, concern with America’s reputation reflects an understanding that the country’s image matters from a self-interested perspective. “If you’re relying on carrots and sticks and have no attraction, and people are repelled by you; it’s going to cost you more carrots and more sticks,” said Nye. A positive global image entices allies and constricts adversaries, all without using force. Between Bush and especially Trump, the United States has ravaged its soft power.

Trump got some things right. “He’s the first president in ages who didn’t start a new war,” said William Ruger, vice president for research and policy at the Charles Koch Institute and Trump’s final nominee as ambassador to Afghanistan. Trump provided a critique of the consistent interventionism that defined post–Cold War foreign policy. But his administration was disastrous in virtually all other aspects, from inflating the threat from China to hollowing out the diplomatic corps.

To its credit, most of the foreign policy establishment opposed Trump. Democrats, of course, were uniformly horrified by Trump’s contempt for allies, affection for tyrants, and his nativism, ignorance, and impulsivity. But so were most Republican officials. Before he won the 2016 election, 50 GOP national security experts warned that a Trump presidency risked the nation’s security and well-being. Four years later, 70 Republican officials, including two who served in the Trump administration, endorsed Biden for president.

But these and other actions demonstrated the GOP foreign policy establishment’s estrangement from actual Republican voters, who adore Trump. “Part of Trump’s resonance in 2016 for sure, and why a lot of Republican voters are wary of others in the party, is because of the fact that he offered a different approach to thinking about America’s engagement with the world,” said Ruger.

While Trump’s affection for Russian leader Vladimir Putin and erratic outreach to North Korea have no parallel in U.S. history, his xenophobia and militarism are classically Jacksonian.

Phase Four: Moderate Internationalism

Biden is the first president since 9/11 to take office with the public understanding that China, not the Middle East, is the major security challenge for the United States. This reflects reality—the Sino-American competition is on. But the war on terrorism era is not over. From the continued troop presence in Iraq and Syria to widespread Islamophobia to countless wounded warriors to the open-ended congressional laws authorizing the president to use force, the terrorism era continues.

Fortunately, Biden ended the futile 20-year attempt to construct a functioning state in Afghanistan, pulling out American troops. “If we haven’t achieved anything in 20 years, we’re not going to achieve anything in another 20 years,” said Anatol Lieven, a Russia and Middle East specialist at Georgetown University. Biden’s move was an implicit admission of the falseness of the post-9/11 belief that U.S. power was unlimited. California Representative Ro Khanna said, “I think [we progressives have] had a huge impact on foreign policy.” He points to the Afghanistan pullout, an increased reluctance on drone strikes, and momentum to repeal the open-ended 2001 and 2002 authorizations for presidents to use force in Iraq and elsewhere in the name of the war on terrorism.

However, Biden has delayed rejoining the Iran deal, insisting that Iran rejoin the agreement first and be open to a larger pact that addresses other issues, such as Iran’s development of ballistic missiles and support for proxies in Syria, Yemen, and elsewhere. “From the Biden administration’s perspective, simply rejoining without some movement from Iran would appear too concessionary and perhaps lose already brittle support in Congress,” said Jonathan Stevenson, now a senior fellow at the International Institute for Strategic Studies. Iran has increased enriched uranium in violation of the deal, which is closer to expiration anyway. “The Trump administration did not leave them with a whole lot of great options,” said the American Enterprise Institute’s Kenneth Pollack, an influential advocate of the Iraq War who also supported the Iran deal. “When Trump pulled us out of the [Iran deal], it enormously advantaged Iran’s hard-liners, justified their entire argumentation, and, as a result of that, it put Iran hard-liners very much in the driver’s seat right now.”

The Biden administration’s approach to terrorism and the Middle East so far looks similar to Obama’s. Indeed, an analysis by the Miller Center at the University of Virginia found that 74 of the 100 key positions in the Biden White House have been filled by individuals who served in the Obama administration. But, so far at least, Biden isn’t replicating Obama’s outreach to adversaries and frequent drone strikes.

The Dawn of Sino-American Competition

Twenty years after 9/11, the War on terrorism is being eclipsed by a greater security challenge. Biden is convinced that China has “an overall goal to become the leading country in the world,” displacing the United States. For its part, the GOP has largely united around overhyping the threat China poses. “Trump really crystallized an ongoing shift in the Republican Party of skepticism vis-à-vis China,” a development that will continue, said Hal Brands of the American Enterprise Institute. “Anybody who comes to the presidency from the GOP side in 2024 or after will be a subscriber to the notion of getting tough with China.”

The bipartisan front has benefits. In June, Congress passed a sweeping bill providing $250 billion in funding for technology research and manufacturing, hoping to bolster America’s ability to compete with China. “There is a surprising degree of agreement between, let’s call it the Trump tribe, and the internationalist tribe,” said Joseph Nye, pointing to this legislation.

Some Democrats say the United States should prioritize human rights, pressuring China to stop its genocide against the Uyghur people and respect individual liberties. “Stressing human rights issues is about stressing the different systems, and the differences between the systems,” said Daalder. “It isn’t used as a cudgel to undermine the Chinese regime’s leadership, or the Chinese regime period, in the way that [former Secretary of State Mike] Pompeo and some other people do.”

But the potential drawbacks to an ideological competition with China are high. Already, anti-Chinese sentiment has spilled over to hostility against Asian Americans. A report from the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism found hate crimes spiked during July 2018 when the United States and China disputed tariffs and the Trump administration reveled in anti-Chinese bigotry. “The attempt to tie Covid to China, calling it ‘the China virus’ and all that, that you saw Trump and Trump Republicans doing, has already had a tremendous impact,” said Katrina Mulligan, who worked at the Justice Department and NSC during Obama’s presidency. She pointed out that, unlike Russians, America’s primary foes during the twentieth century, Americans of Asian descent look different than white people, making them easy targets for bigots wanting to act on Sinophobia. It’s extremely difficult to compete with China, opposing its human rights violations and authoritarianism, while simultaneously countering homegrown xenophobia, McCarthyism, and racism. “I don’t think we know how to do it,” said Heather Hurlburt, who leads New America’s New Models of Policy Change project. “The universe of people who are willing to act on both of those ideas is vanishingly small.”

Most alarmingly, the dangers of a nuclear war will grow from increased China-U.S. tensions. Presuming that China continues to gain strength, it will have additional power to assert its interests. That presents challenges to U.S. dominance, particularly in East Asia. “It’s an important moment when one significant power is passing or catching up in overall capabilities with another significant power,” said MIT’s Barry Posen, a leading advocate of a foreign policy forefronting restraint. Flashpoints like Taiwan and Hong Kong are particularly dangerous, since the United States has staked its credibility on defending lands of little strategic importance, but which China considers essential to its territorial integrity. “This requires a kind of subtle foreign and defense policy, and that’s not our strong suit,” he said.

Lessons from the 9/11 Era

In environments like this, modest, prudent, long-term strategy is indispensable. So are prioritizing vital interests, reducing unnecessary conflict, and husbanding resources. Alas, the story of U.S. foreign policy since 9/11 is largely a story of squandering human lives and wealth, recklessly damaging the country’s valuable capabilities and soft power. America’s supreme position in the 1990s meant that it had a huge cushion of power to squander through failed military interventions, trillion-dollar wars, and wasteful defense spending. But that cushion has shrunk. Al Qaeda failed in ejecting the United States from the Middle East—the nation still supports repressive governments in Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Israel, and elsewhere. But the 9/11 attacks were wildly successful in pushing the United States to engage in profoundly destructive acts that damaged U.S. security, to say nothing of the lives lost elsewhere.

America’s supreme position in the 1990s meant that it had a huge cushion of power to squander through failed military interventions, trillion-dollar wars, and wasteful defense spending. But that cushion has shrunk.

In small ways, because of the consistent string of failures, Washington has become friendlier to the idea of a foreign policy oriented around restraint or retrenchment. The Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft, a think tank founded in 2019, is a vital counterweight in offering the media and lawmakers policy-relevant research from a perspective that sees U.S. power and interests as limited and selective rather than inexhaustible and global. “Restraint is now part of the conversation,” said Andrew Bacevich, the institute’s president. “But I don’t think something like any kind of a deal has been closed.”

There does appear to be at least a temporary injunction in Washington on trying to build states abroad. As Khanna said, the country is now “more cautious about the ability of military interventions to transform societies. Do I think that there could be overreaction still on civil liberties and certain misguided forays of foreign policy? Of course, but I do think that we’ve learned the lesson of Iraq.”

But it’s not clear that members of the foreign policy establishment believe their track record is spotty. “If you do the balance of where we are today and what we’ve done after 20 years, the war on terror certainly has been a lot costlier than we wanted, with very imperfect results in the region, for the quality of life and governance in the Middle East—but it’s actually still been somewhat successful,” said Michael O’Hanlon. Kenneth Pollack noted that, while the Iraq War was horribly mismanaged and the United States made other mistakes, “back in 2001, nobody believed that, over the next 20 years, there wouldn’t be another major terrorist attack.”

These accounts suggest that Al Qaeda’s inability to replicate its attacks means that U.S. strategy has been effective and wise. That assessment underestimates the scale and frequency of foreseeable U.S. failures in favor of praising an outcome that would have been easier to attain without spending trillions of dollars and causing the deaths of hundreds of thousands. It’s like a person needing a car worth $25,000 who spends $1 million on the car at a dealership, has a few drinks while driving it home, receives a few speeding tickets, and causes a hit-and-run that kills somebody—but who declares success because he did, in fact, get the car.

What’s more, policymakers in both parties and some foreign policy intellectuals overlook maybe the key lesson of the past 20 years, which is that the use of armed force often weakens America’s international position. Democrats and Republicans alike worry that reduced U.S. influence globally would be replaced by China, Russia, Iran, or other nefarious actors. But this assumes that the United States is endangered whenever other countries exercise power. “Foreign policy should be about interests, not vacuums,” Barry Posen said. “If your interests don’t lie in a place, why do you care?”

The country could use its power advantageously. Few things would benefit the United States more than converting enemies and challengers through tough-minded diplomacy rather than perpetually trying to coerce them with sanctions, bombastic rhetoric, or armed force. The Iran deal, Russia’s commitment to America’s terrorism project from 2001 to 2003, and China’s continual ideological shifts throughout the decades suggest that skillful, creative diplomacy and due recognition of the interests of other countries can reduce tensions, offer opportunities for cooperation, and prevent the emergence of coalitions that balance against the United States. “Trying to befriend adversaries is an important tool of statecraft that often gets overlooked,” said Charles Kupchan, author of How Enemies Become Friends: The Sources of Stable Peace.

Domestic challenges and intense political polarization make robust diplomacy and peacemaking difficult, however, not just with the Taliban circa 2002 but perpetually. “There’s always a nationalist waiting in the wings to say you’re selling out the country, you’re being weak in the face of danger,” Kupchan said. Forefronting diplomacy also would mean acknowledging other countries’ interests, dealing directly with adversaries, and accepting imperfect agreements. Because the best way to secure the United States is to preserve its power, narrow its list of vital interests, and build a better country at home, not squander blood, treasure, and soft power in the futile pursuit of global dominance and armed humanitarianism. That is a view that hasn’t gained prominence in Washington. It certainly didn’t after 9/11. Perhaps one day it will.

For better and worse, the foreign policy establishment is weaker and more fragmented than it has been since the end of the Vietnam War. But it still exists, and it has tentatively learned some things from the wasteful, counterproductive, and sometimes disastrous U.S. foreign policy performance of the last 20 years. “The real problem with Afghanistan was the decision to try to occupy the country, and to try to eradicate the Taliban, and transform it,” said Kenneth Pollack. “I think that we’ve learned that that was ultimately impossible.”

But even the withdrawal from Afghanistan is highly controversial among some of the elite. And the demonization of other countries and peoples, the inability to understand the worldview of challengers and adversaries, the overreliance on force: these traits remain, because they were ingrained in Washington long before 9/11. Because of its unchallenged international position, the United States was able to make major mistakes for two decades after the Twin Towers fell and still emerge predominant. However, with an emerging China possessing nuclear weapons, a growing economy, the world’s biggest population, and expanding demands, the United States cannot afford another 20 years of failure.

No comments:

Post a Comment