Ekaterina Zolotova

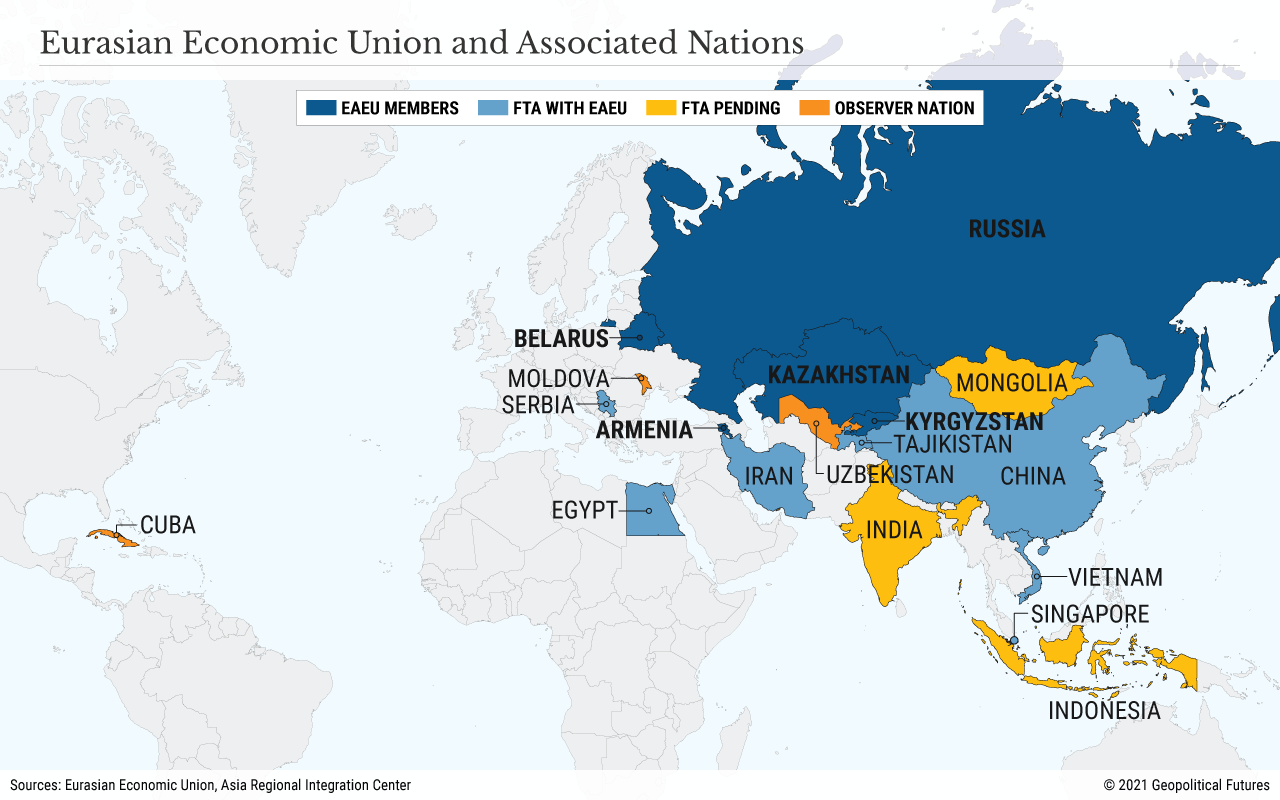

While Russia was grabbing attention with its buildup and withdrawal of military forces along its western border with Ukraine, it was making a different, diplomatic advance in another buffer region: Central Asia. On April 30, leaders from the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) – Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Russia, as well as observer states – gathered in Kazan, Russia. A few days before the meeting, Russian Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu traveled to Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, which is an observer member of the EAEU. Of course, Russian cooperation with the countries of Central Asia is nothing new. But the meetings were emblematic of a shift in Russian strategy away from the ad hoc approach of past decades and toward something more coherent. Facing rising competition for regional influence, and with diminished political and economic capital to impose its will, Moscow is trying to build up the EAEU and lead by subtler means.

Haphazard Strategy

The Soviet Union, by expanding Moscow’s borders, gave Russia immense security. This security was lost when the USSR collapsed. Once Russia stabilized itself, it devoted more attention to its western frontier, which harbored the more immediate threats of NATO and EU encroachment. The Central Asian states, meanwhile, remained more closely tied to Russia. In addition, the countries of Central Asia had territorial disputes with one another, which reduced the chances that they would merge into a union capable of resisting Russia.

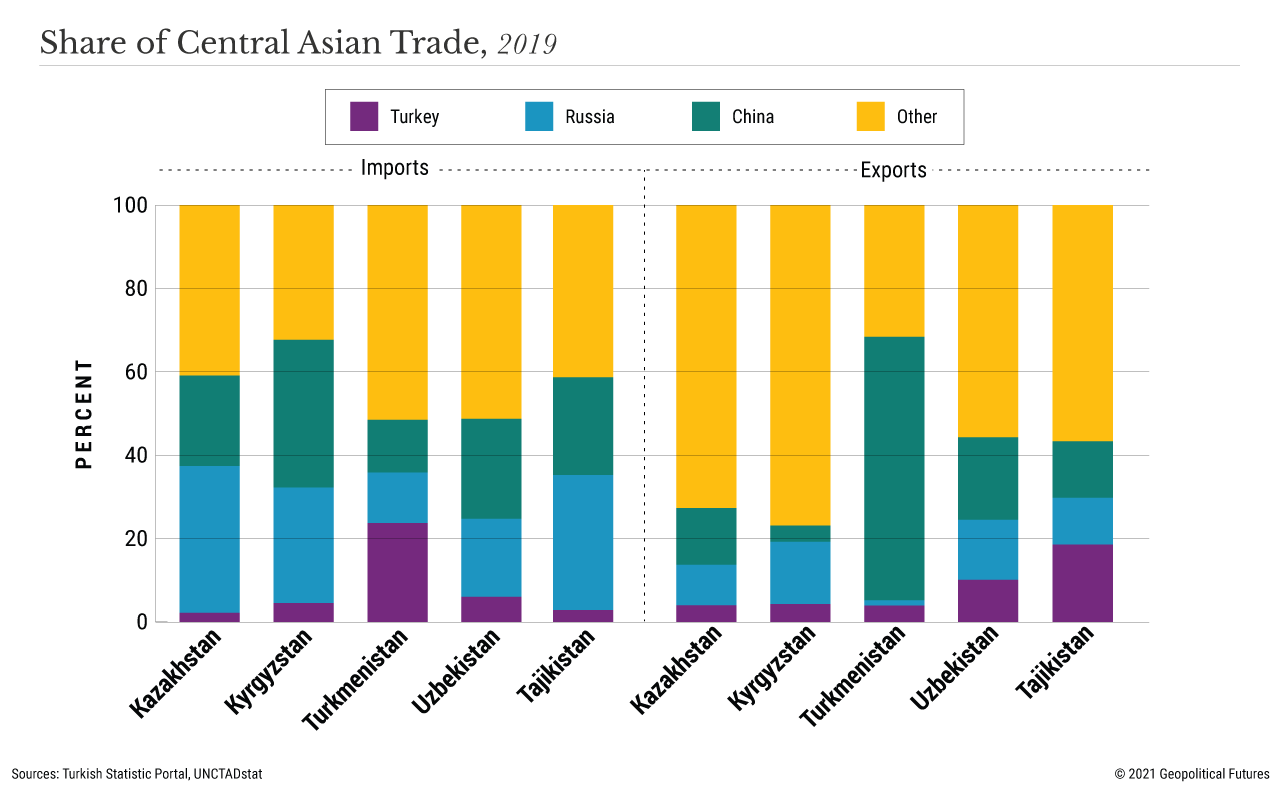

But Central Asia is still a critical region for Moscow. It forms a buffer separating Russia from China and the rest of Asia. Especially important is Kazakhstan, which has no natural barriers with Russia, meaning instability in the former Soviet republics of Central Asia can easily spread into Russia itself. It is also important for Moscow to protect its significant industrial potential concentrated along the Kazakh border, as well as communications linking the central part of Russia with Siberia and the Far East, which run either near or through Kazakhstan. Finally, Central Asia has the potential to become one of the most actively developing regions in the world for the production and transportation of oil and coal, attracting the attention of outside players like the United States, Iran, Turkey and China.

Yet, until the 2020s, Russia had no coherent strategy for Central Asia. Instead, its approach often looked chaotic and uncoordinated. In general, it has tried to maintain its influence by distributing loans and strengthening its military presence. In the first decades after the fall of the Soviet Union, Russia directed economic assistance and mostly unprofitable investment to the region – roughly $20 billion worth, about half of which (47 percent) went to the energy sector, with another 22 percent going to nonferrous metallurgy and 15 percent to telecommunications. Russia also continued to act as the security guarantor of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan within the Collective Security Treaty Organization, and built Russian military bases and facilities in the region.

This policy often met with criticism from the Central Asian countries, which had just gained their independence and did not want to auction it off in exchange for Russian loans. It was also unpopular with many Russians, who were unhappy not only with the large number of Central Asian immigrants but also with the government’s allocation of support to the republics rather than Russia’s own sluggish economy.

New Direction

Almost 30 years later, the Kremlin recognizes the need for a more thoughtful and balanced policy. The countries of Central Asia are no longer lost pieces of the Soviet Union but fully independent states with their own foreign relations and no interest in giving up their sovereignty. There are several reasons for Russia’s change of heart.

First, there’s rising competition: Moscow is no longer Central Asia’s only important trading partner and creditor. Second, Russia is approaching or has reached the limits of its western strategy and is up against increased political pressure on that front. Over the past year, Russia has significantly bolstered its relations with Belarus, and its enormous military drills in and around Crimea last month demonstrated that Kyiv and Moscow understand their own limits and what to expect from each other. In the east, however, Russia still needs to develop its strategic depth and further open trading markets. Third, the Kremlin accepted that its previous policy toward Central Asia was just not very effective and actually ignored the territorial disputes in the region, which today are at risk of flaring up. Under its old policy, Russia had no mechanism for resolving potential military conflicts – like last week’s clashes between Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan – since Russian military involvement was impossible because Moscow prefers to maintain equally good relations with all parties. Also, the introduction of Russian peacekeepers in the region would likely cause a negative reaction from the West.

Other factors likely played a role as well. For example, the pandemic highlighted all manner of existing and potential dangers: economic inequality, massive hidden unemployment, reduced remittances due to social distancing measures, the risk of economic crisis and the ineffectiveness of political and administrative systems. Social and economic unrest could be a boon for the recruitment efforts of local terrorist groups. Also, the Biden administration returned to the so-called C5+1 (the five republics of Central Asia plus the U.S.) and began discussing the possibility of setting up military bases after the withdrawal of U.S. and NATO troops from Afghanistan. Turkey’s president, meanwhile, suggested formally upgrading the Cooperation Council of Turkic-Speaking States. Finally, the volatility of oil prices and the modest growth of the Russian economy were threatening Russia’s investment approach to the region.

Influence Over Control

The details of the new Russian approach still need to be worked out, but it will run through the Eurasian Economic Union, which is not just an economic bloc but also a political forum. Russia can no longer hope to dominate the region – at least not at a price it’s willing to pay. The Kremlin’s future influence will instead be based on psychological warfare and inducements, not direct intervention. To that end, it is important for Russia to show that cooperation with it or with Russian-led projects is a mutually beneficial process, and that its partners will not lose their independence but rather gain influence. The recent Tajik-Kyrgyz conflict is a vivid example of Russia using the EAEU as a platform to resolve a conflict instead of deploying its own peacekeepers or negotiating separately with both sides.

The military aspect is also changing. Moscow no longer seeks to build up Russian forces in Central Asia, but instead prefers to create a platform for burden-sharing and joint cooperation in which every participating country feels that it is an important and full-fledged member. For example, Russian Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu initiated the formation of an anti-Taliban front during his last visit to Uzbekistan. This is supported by the creation of a joint air defense system with Tajikistan and the new strategic partnership with Uzbekistan. The latter headed off an initiative from Washington, which hoped Uzbekistan would serve as a reserve base for countering terrorists in Afghanistan after the withdrawal of Western troops.

If its new strategy works, then Russia will be able to increase its importance in the region at minimal cost. More important, it will do so without triggering a backlash from third countries. China is unlikely to oppose it, since Beijing needs a stable Central Asia to implement its Belt and Road strategy. Moreover, if the countries of Central Asia represent one economic space, then the transportation of goods will encounter fewer bureaucratic obstacles. Iranian ambitions in the region can also be gently controlled by Russia, especially if Russia succeeds in attracting Iran to the EAEU, which could help Tehran circumvent U.S. sanctions. Turkey’s economic ambitions in the region will be forced into the background, and a strong Russian presence will reinforce Russian culture and block pan-Turkism from taking root. Finally, if the EAEU represents a platform for negotiations where countries are not dominated by Russia, then Western countries are also unlikely to find a reason to threaten the project with sanctions.

But such a strategy means that Russia will have to settle for increased influence rather than total control and make a number of concessions. Already Moscow has experienced the consequences of the introduction of consensus in the EAEU, when Armenia opposed Azerbaijan’s participation in a meeting of the bloc’s intergovernmental council, against Russia’s wishes. The Kremlin will have to get used to moving more slowly and not always getting its way. The only questions are whether the Kremlin will have the patience and time to implement its new strategy and, more important, whether the Central Asian countries will trust Moscow’s peaceful intentions.

No comments:

Post a Comment