Shumin Cao

October 1, 2019 was a markedly violent day. An 18-year-old was shot in the chest with a live bullet as protesters fought police with petrol bombs. In early November, a pro-Beijing lawmaker was stabbed in the street by a man pretending to be a supporter. Then, throughout December 2019 and January 2020, the intensity and frequency of protests decreased, corresponding to the phase of ceasefire and normalization in Ramsbotham’s model (2016, p. 11). While the pro-democracy camp achieved electoral success, the siege of the Polytechnic University led to mass arrests. In January 2020, the Hong Kong government imposed strict restrictions on gatherings to control the spread of COVID-19. Mass demonstrations have been halted since then, although small-scale protests are still ongoing.

The protests’ media coverage was largely polarized, especially on the issue of violence. Some criticized the Hong Kong government for oppressing citizens. Others emphasized the need to maintain law and order. This paper focuses on the British newspaper The Guardian and the Chinese newspaper People’s Daily. How do these two different media outlets narrate the violence integral to the 2019-20 Hong Kong protests?

Framework

Sociologist Erving Goffman (1974) conceived reality as a “schema for interpretation,” where “framings” are people’s interpretations of situations. Snow (2000) and Benford (2000) expanded the concept of framing into an approach for studying social movements. They posited three ways of constructing frames, calling them “core framing tasks” (2000, p. 615). The first – “diagnostic framing” – delineates “how the problem is defined”; it is, essentially, assigning blame. The second – “prognostic framing” – is about proposing solutions to the problem. The third – “motivational framing” – is the impetus to act and motivate the audience, including constructing the appropriate vocabulary (Snow & Benford, 1988). Accordingly, my analysis unravels the three phases of the Hong Kong protests through the concepts of diagnostic framing, prognostic framing, and motivational framing, with particular attention to the issue of violence.

I selected 20 news reports published in The Guardian and the People’s Daily from June 2019 to January 2020, that is, spanning the escalation and de-escalation of the conflict. Journalistic quality needs cultural understanding, that is, considering social, political, economic, religious, and historical factors when reporting on complex matters (Bebawia & Evans, p. 65). Accordingly, I only selected news reports written by local journalists, based in Hong Kong.

The Guardian is a newspaper based in London; it is generally regarded as left-leaning. The People’s Daily is an official newspaper of the Chinese Community Party. That being said, the analysis is – emphatically – not about pitting a Western democratic source against non-democratic Chinese state media. Rather, I seek to understand how an international, non-government source (The Guardian) on the one hand, and a domestic government source (People’s Daily) on the other hand, narrate a violent civil conflict.

Analysis

The analysis proceeds in two parts. First, I calculate the ratio of positive to negative coverage of the use of violence. I label reports as positive if they suggest that the use of violence is in some way linked to a positive outcome. Positive coverage generally refers to ideas such as: violence is inevitable; violence is a worthwhile sacrifice; violence is a means to an end – bringing peace.

For instance:

“We used to protest peacefully but it did not work, now we need to get out of this framework and tell them, we’re willing to try anything until you give us an answer.” (Verna & Christy, 2019.7)

“I accept revolution and bloodshed. Revolution is a war and no war are without violence … If our violence can bring about positive changes, I am willing to be involved.” (Verna, 2019.8)

Similarly, I label reports as negative if they suggest that the use of violence is in some way linked to a negative outcome. Negative coverage generally refers to ideas such as: violence is avoidable, violent protesters conceal their true motives, violence affects the lives of Hong Kong citizens and damages Hong Kong’s economy and international image.

For instance:

Police have fired 10,000 canisters in protests, sparking health scare over possible harmful effects. “Police have thrown teargas all over the city – some of my friends say their children have come out in rashes,” Chan said. “I simply don’t know where to find a safe spot anymore.” (Verna, 2019.12)

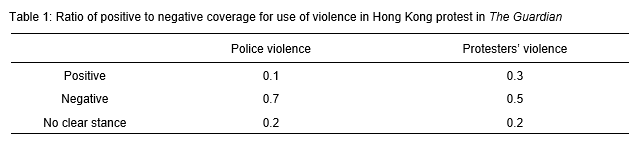

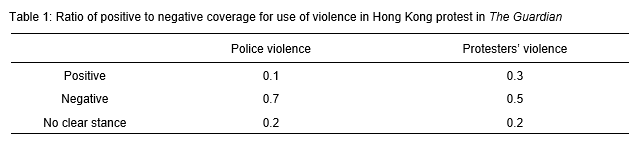

Concerning The Guardian’s reporting on police violence, 10% is positive, 70% is negative and 20% does not convey any clear stance. About protesters’ violence, 30% of the reporting is positive, 50% is negative and 20% does not convey any clear stance (see Table 1).

In addition, The Guardian’s positive reports on the use of the violence by protesters mainly focus on the early stage of the protest, corresponding to the “difference and contradiction phase” in the escalation and de-escalation model (Ramsbotham, 2005). While in the phase of violence and war, the reports hold negative attitudes toward both sides using the violence in conflict. This shows that when conflict becomes fierce, both parties are likely to be in an irrational state. For the overall judgment on the use of violence in The Guardian, whether it is for police violence or protest violence, the negative reports outweigh the positive ones.

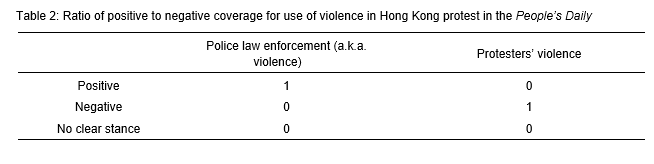

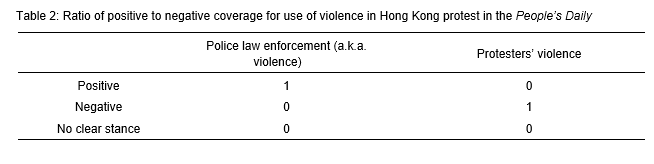

When referring to the police, the People’s Daily does not use the terms “violence” or “use of force,” but rather “law enforcement,” hence denying the possibility that the police could be violent. The People’s Daily has a clear stance and fully supports the lawful law enforcement of the Hong Kong police and unreservedly condemning any and all forms of violent protest: 100% of positive reports of the Hong Kong police in law enforcement, 100% of negative reports to protest violence, and 0% of no clear stance (see Table 2).

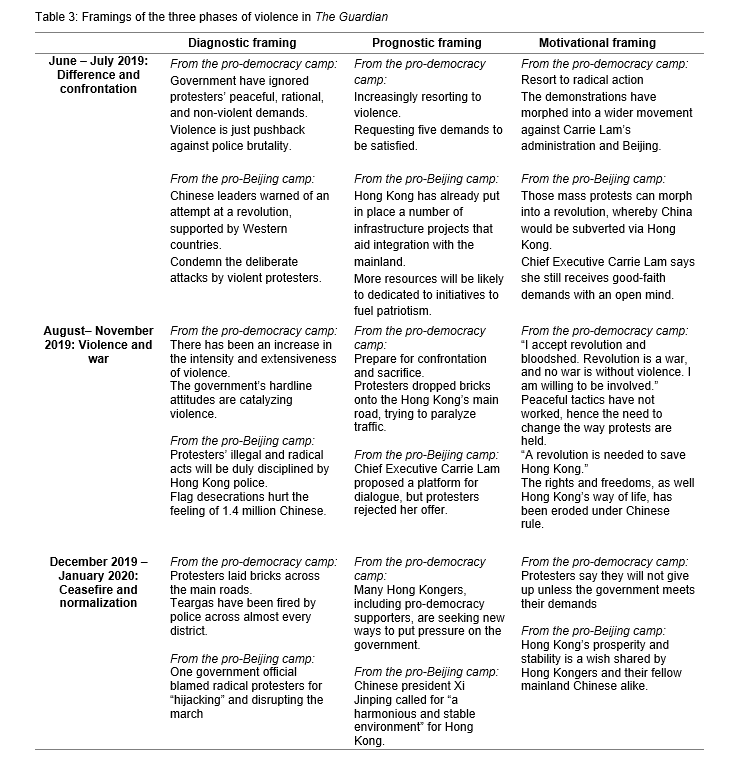

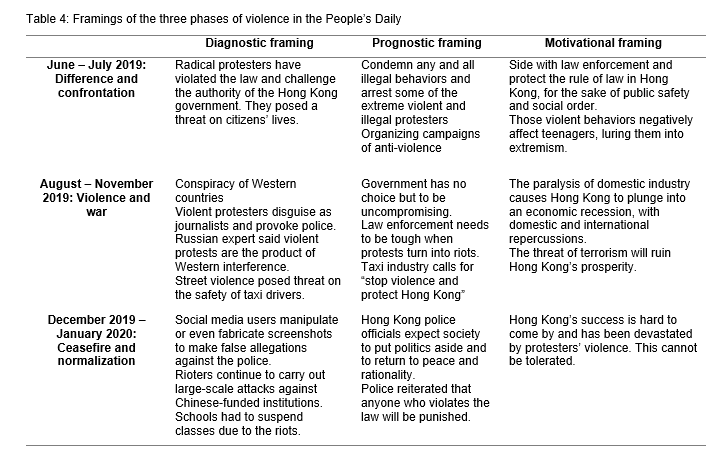

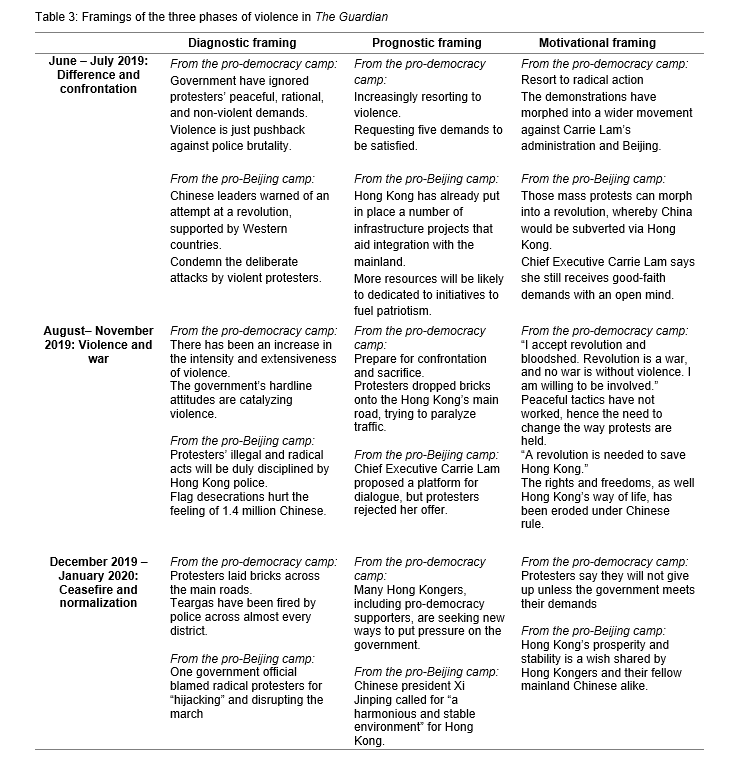

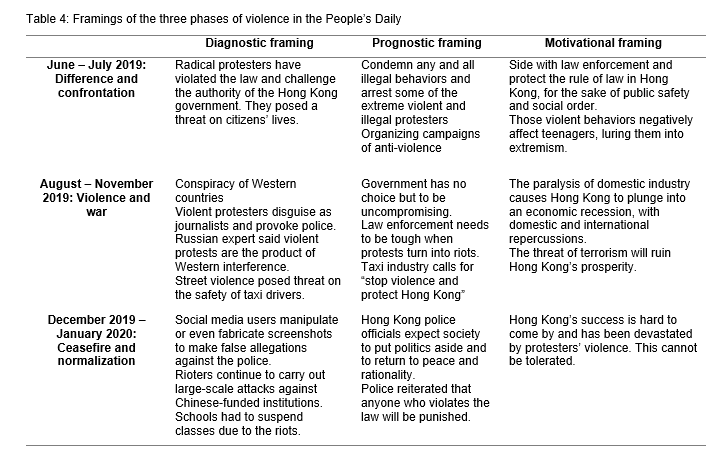

Second, I examine how the use of violence is framed, throughout the three phases of the conflict, in The Guardian (see Table 3 below) and the People’s Daily (see Table 4 below).

In the first phase, The Guardian slams the Hong Kong government for using violence illegitimately, which hits a key point of diagnostic framing: assigning blame. The Guardian calls out the government’s ignorance of protesters’ rational and peaceful demands, hardline attitude, and tolerance for police brutality. Characteristically, prognostic framing is about solutions and proposals: protesters propose plans varying from turning to peaceful tactics to intensifying violence. Per the motivational framing, protesters’ slogans emphasize the movement’s urgency and significance, and associate their individual behaviors to Hong Kong’s future.

For instance:

“Hong Kong needs a revolution and revolution requires blood, we are willing to sacrifice,” “We are fighting for the freedom and human rights of Hong Kong, which is the foundation of Hong Kong.”

The Guardian also reports the framings carried by the governments of China and the Hong Kong SAR. In the first phase, they condemn any form of protests and regard violence as part of an attempt at a revolution, and what is more, a Western conspiracy aiming to subvert Hong Kong and China. In the second and third phases, they continue to condemn violence and stress the need to punish lawbreakers. At the same time, the Hong Kong government showed more flexibility, even initiating dialogue with the protesters. Chinese president Xi Jinping gave a speech communicating the determination of mainland China to rebuild Hong Kong’s harmony, which observers interpreted as a will for closure.

The People’s Daily elevates the views of the pro-Beijing camp, including the governments of China and the Hong Kong SAR, the Hong Kong police, citizens, and even Russian experts. All reporting shares a master narrative: opposing any and all forms of violence for the sake of public safety. By the same token, the People’s Daily does not make any mention of the protesters’ views, positing their behaviors as violent, illegal, and in need of correction.

In comparative perspective, The Guardian acknowledges that both police and protesters have behaved violently during the conflict, and judges whether such violence is positive or negative based on the conflict’s context. The People’s Daily does not think there is a phenomenon of police violence. It explains it as law enforcement: in response to escalating mob violence, the police maintained law and order.

As an international newspaper, The Guardian enjoys more flexibility in its reporting. The content mainly depends on the reporter’s own observation and judgment. By contrast, as a domestic source, the People’s Daily expresses a consistent stance, conveying the narrative of the Chinese Communist Party to the public opinion.

Conclusion

The narratives of The Guardian and the People’s Daily are markedly different. The Guardian’s reporting is based on specific events of the conflict. This usually entails describing events in detail, identifying all its actors, unraveling the conflict process, understanding points of contention, and discussing the use of violence by both parties. There are various views on the use of violence by both parties, views that are based on the incident itself and that are not predetermined.

The People’s Daily’s coverage is characterized by its grandness and comprehensiveness; It does not usually detail the ins and outs of the incident. It holds a single view on the use of violence: supporting police enforcement of the law against violent demonstrators. The People’s Daily holds a preconceived view on violence, arguing that any form of violence is wrong and should be condemned, whereas The Guardian tends to evaluate the violence based on original intent.

Tables

No comments:

Post a Comment