FRED KAPLAN

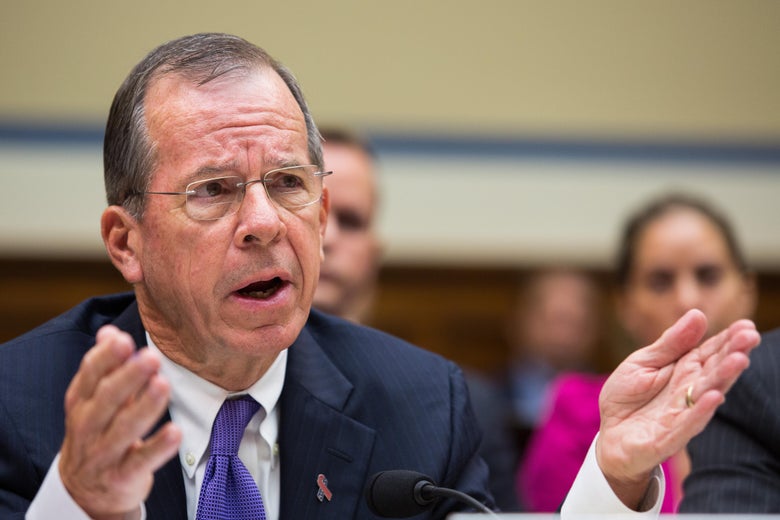

Retired Adm. Mike Mullen, the top U.S. military officer under Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama, who strongly supported the “nation-building” war policy in Afghanistan, now says we should have pulled out our troops a decade ago, soon after Osama bin Laden was killed.

Mullen is thus far the only senior officer from that period who has publicly admitted that the U.S. policy—and he personally—was deeply mistaken. “It’s hard to deny the evidence in front of you,” Mullen said to me in a phone interview Monday morning.

Mullen—who was chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff from October 2007 till September 2011—first admitted his mistake on this past Sunday’s episode of the ABC News show This Week. On the show, he also gave credit to then–Vice President Joe Biden, who at the time opposed the troop surge and a switch to a nation-building strategy. Biden “had it right back then,” Mullen said, and “I give him credit for that.”

In our phone conversation the next morning, Mullen acknowledged that, back in 2009, he and all the other top officers and officials advised Obama to send 40,000 more troops to Afghanistan and to adopt a nation-building strategy. Biden was alone in calling for merely an extra 10,000 troops and to restrict their activities to training the Afghan army and fighting terrorists along the Afghan-Pakistani border. “He got it right,” Mullen said of Biden. “It would be hard to argue that [Biden’s proposal] wasn’t the right way to go.”

Mullen said that he and his fellow officers got two big things wrong. First, he said, “We underestimated the impact of corruption.”

“Keeping al-Qaida at bay” was clearly in U.S. interests, but “it was not a reason to stay.”

Even at the time, Mullen stressed the importance of stopping corruption within the Afghan government. At a Senate hearing back in September 2009, a few months before Obama decided on a war policy, Mullen testified, “The Afghan government needs to have some legitimacy in the eyes of the people. The core issue is the corruption. … It’s been a way of life for some time, and it’s just got to change. That threat is every bit as significant as the Taliban.” Sen. Lindsey Graham, noting that the Taliban were gaining ground because of this corruption, asked, “We could send a million troops, and that wouldn’t restore legitimacy in the government?”* Mullen replied, “That is correct.”

The corruption never ended, yet Mullen continued to support the war effort. In our interview, he recalled a 2011 scandal at Kabul Bank, in which Afghan insiders embezzled $850 million—all U.S. taxpayers’ money—and spent it on personal luxuries. “We had the goods on them,” Mullen recalled. An anti-corruption agency, led by U.S. officials, had been created to go after these sorts of crimes. But the administration “chose not to prosecute,” he said. “I realized right then that this was politically going nowhere.”

And yet, he admits, he continued to support a war strategy that depended, among other things, on wiping out corruption in order to win the hearts and minds of the Afghan people.

The other big mistake, Mullen said: “We underestimated the significance of our presence, in all that we were doing.” First, American trainers created an Afghan army in their own image, heavily reliant on U.S. close-air support, intelligence, logistics, helicopter transport, repair, and maintenance. When this combat support was withdrawn, he said, collapse was almost inevitable. There was a more intangible side of this dependency as well—“the confidence they got by having us there.” He added, “Their soldiers fought—tens of thousands died.” When they saw that we were leaving, the wind went out of them, and so they made deals with the Taliban or simply fled.

And yet, Mullen admits, he sat at the pinnacle of the U.S. military machine back when this dependency was molded.

Most of Mullen’s colleagues from the Bush and Obama era have continued to defend the decision to escalate the war; none have taken responsibility for any strategic miscalculations. Retired Gen. David Petraeus, former commander of U.S. forces in Afghanistan, has said that, if we’d pull out the troops after killing Osama bin Laden, al-Qaida would simply have returned.

Asked about this claim, Mullen said that Petraeus, with whom he worked closely at the time, makes a “legitimate” point. But, he went on, by 2012, it was “widely believed that al-Qaida was pretty significantly diminished, and that’s where they’ve stayed.” Mullen added, “Keeping al-Qaida at bay” was clearly in U.S. interests, but “it was not a reason to stay”—that is, it was not a mission that required a continued U.S. combat presence, much less a sharp escalation.

Mullen, who now heads a private consulting firm, said that he’s received “tons of email,” much of it from people he barely knew, thanking him for his remarks in the ABC News interview. “A junior officer wrote me, saying how ‘refreshing’ it is, hearing someone in a senior position to admit he got it wrong.”

I asked whether he’d heard from any of his fellow senior officers. “The rest of the silent crew?” he said, with a slight chuckle. “No, I haven’t heard from them.”

No comments:

Post a Comment