Matthew T. Archambault

“Some people can read War and Peace and come away thinking it’s a simple adventure story. Others can read the ingredients on the back of a chewing gum wrapper and unlock the secrets to the universe.”

— Gene Hackman as Lex Luthor in Superman (1978)

Subordinates often ask leaders for suggestions on what they should read. In the Army, professional military reading lists from a range of sources exist, from the chief of staff of the Army to organizations like the Modern War Institute at West Point. Many of these lists’ recommendations are separated by rank or grade while others are separated by categories such as topics like strategy, technology, or operational art. Those lists contain fine suggestions, but a successful reading program, whether personal or organizational, requires purpose. Reading should be done with a purpose in mind. It should not simply be a checklist of what someone else recommended. Regardless of what that purpose is, the time spent should contribute to a goal and leaders have a duty to shape that goal.

Not everyone is a reader. Typically, those with a predilection for reading read while those without the predilection just say they read. Some are even honest and admit to not reading. Regardless of what type of reader you are, reading should be fun. It should be a personal quest to prepare for the next set of challenges that loom over the horizon. As an example, students at the School of Advanced Military Studies (SAMS) must read with a purpose if they are going to pass oral comprehensive exams at the end of the year and be successful planners on division- and corps-level staffs. Their purpose when reading—and it should be the purpose of every soldier who picks up a book, doctrinal manual, professional journal, or online article—is to figure out how that author’s argument fits into their current understanding and visualization of the operating environment, and whether they should alter or refine their understanding. That is the basis for critical thinking. You do not need to seek out the SAMS curriculum to do this. Instead, you, as a reader, must realize that mastering your profession requires, first, grasping the environment in which your trade exists and, second, an exploratory mindset bent on understanding the links between subjects related to that profession.

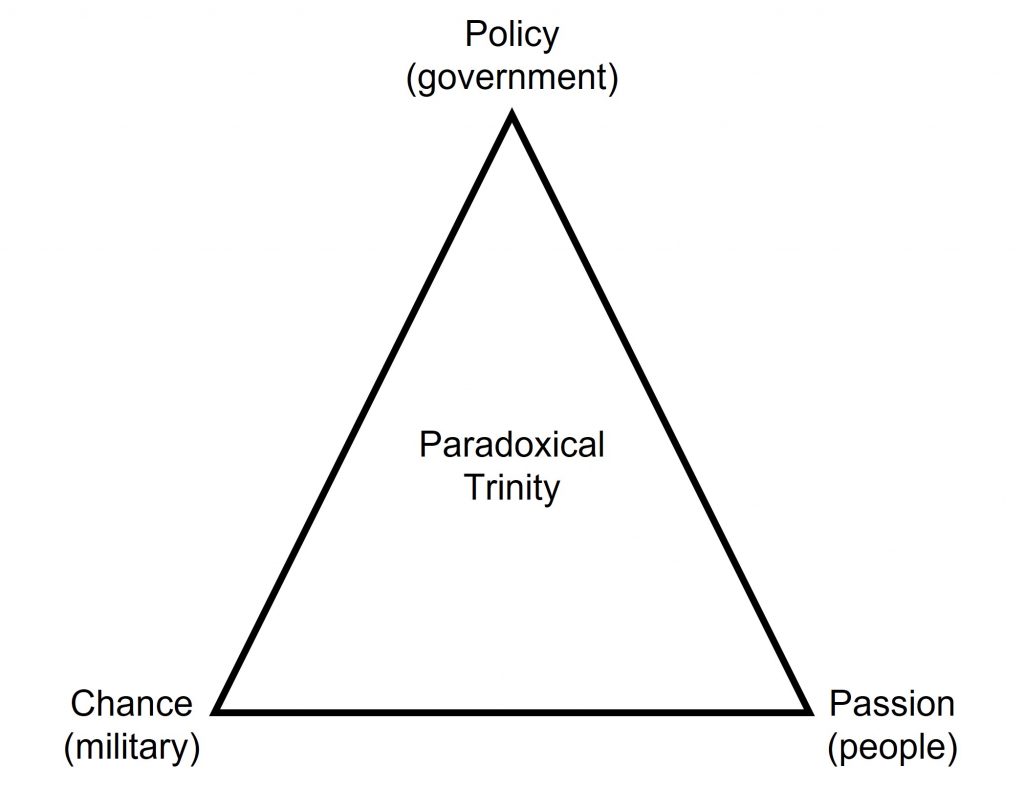

Prussian theorist Carl von Clausewitz showed us the operating environment of our profession when he described his paradoxical trinity. At the end of the first book of On War, he characterized war as “more than a true chameleon that slightly adapts its characteristics to the given case.” Clausewitz posits that no two wars are ever going to be the same. His implication is that the differences between wars are going to matter. The professional student of war must be constantly studying the characteristics of war in order to best anticipate how these characteristics might change and adapt. Clausewitz then proceeded with a description of the paradoxical trinity, composed of (1) “primordial violence, hatred, and enmity,” (2) “the play of chance and probability within which the creative spirit is free to roam,” and (3) “its element of subordination, as an instrument of policy.” He continued in the next paragraph to ascribe to each aspect the monikers of the people, the military, and government. Figure 1 is an illustration of his paradoxical trinity.

The argument is clear. Professional reading must encompass more than doctrine, more than purely military subjects. As Clausewitz’s paradoxical trinity depicts, the military is not an independent entity. These aspects, as Clausewitz called them, have changing relationships to each other. The reader requires a mindset to place the military and military topics into context with those other aspects as they affect the reader’s ability to win our nation’s wars. Anything that might affect the military or military effectiveness might populate the rest of the trinity. Soviet military theorist Alexsandr Svechin argued the same in Strategy, that “a strategist will be successful if he correctly evaluates the nature of a war, which depends on different economic, social, geographic, administrative and technical factors.” These factors populate the paradoxical trinity and should be studied by the professional soldier.

While Svechin offered categories for readers to explore, the reader needs to have an explorer’s mindset about the process. Explorers look to create links that will help professionals on their quest to be well rounded and, ultimately, more effective. To do this, one must see the book and how it connects across Clausewitz’s paradoxical trinity. For example, every officer and noncommissioned officer should read Arthur S. Collins Jr.’s Common Sense Training: A Working Philosophy for Leaders. Collins’s book provides a pragmatic and philosophic foundation for leaders to approach training. To the right reader, the book can serve as a gateway to the rest of the trinity.

Collins’s central themes of leadership and training are two topics vital to a leader’s professional growth. A myopic focus on the leadership or training subjects, though, stymies growth and intellectual exploration. Common Sense Training should lead the professional reader to other books and articles. Leadership requires subordinates, peers, and superiors. Training requires people, equipment, money, and an objective of how that training fits into achieving the goal.

Taking one aspect of the trinity, the soldiers that populate the Army come from society. Thus, the relationship between the military and society matters. The all-volunteer force (AVF) of 2021 trains differently than a conscripted force trained in the 1960s. Leadership concepts changed with the transition from a conscripted force to an AVF. The AVF is very dependent upon the health of the economy. The military, particularly the Army, struggles to recruit and retain when unemployment is low and the economy is good. Thus, an understanding of economics improves the reader’s ability to serve the nation.

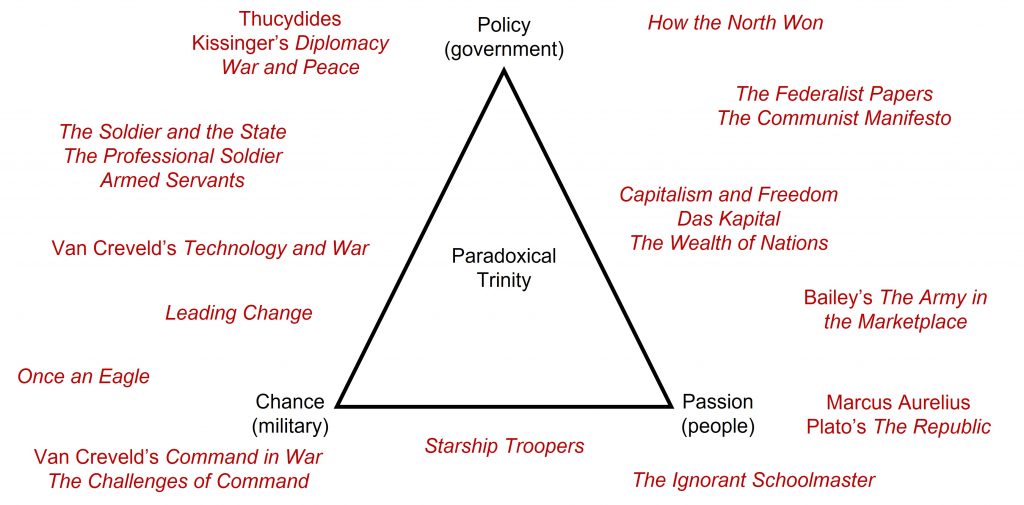

But economics are not the only potential topics that Common Sense Training should have a reader examine. Figure 2 illustrates an example of topic options available based on what else a leader should consider when reading Collins’s book. The topics shown are by no means exhaustive. The professional is responsible for determining how Collins’s forty-year-old message resonates in the current environment.

Pursuing Clausewitz’s reading strategy (i.e., making the decisions about reading the last paragraph described) requires an exploratory mindset that places the reader at the upper tiers of Bloom’s Taxonomy. The SAMS faculty cajoles students all year to go beyond regurgitation of someone else’s ideas. Professionals cannot take what they have read at face value. There are not only connections a reader must make, as described with Collins’s book, but also the author’s agenda to identify and assess. As John Keegan lamented in The Face of Battle, military history is a highly politicized subject and these skills of synthesis and evaluation are crucial if professional military readers are to use concepts effectively and creatively. Creativity and the freedom to intellectually roam, as Clausewitz described, exist at the top of the taxonomy because the reader is making connections and links between what might otherwise seem disparate topics. If only regurgitating what he or she has read, a reader lacks creativity and is a slave to another’s assumptions and intent.

Professional reading does not have to be boring doctrinal manuals or dry battle histories. There are a wide variety of options, both fiction and nonfiction, that are available to broaden the military professional’s perspective. Figure 4 provides some options for readings that flow from the topics identified when professionally reading Common Sense Training. These examples were identified when analyzing what impacted leadership and training as presented in Collins’s book. The possibilities are endless. A reader with such an exploratory mindset can generate his or her own book list by pursuing the questions posed during exegetical reading.

Heraclitus said, “No man ever steps in the same stream twice, for it’s not the same river and he’s not the same man.” Collins’s book is a must-read for every lieutenant or sergeant, but that leader does not remain a lieutenant or sergeant forever. The value of Common Sense Training to a platoon leader changes when that leader is at battalion, brigade, or corps. Rereading a book provides an opportunity for him or her to glean new insights based upon the experiences and learning of the intervening years. Through reflection and analysis, a professional reader who reflects on what has changed since his or her last reading of a book will succeed in contemplating issues from atop Bloom’s Taxonomy.

Finding things to populate one’s reading list should never be the issue. The challenge for the individual looking to read with a purpose, and for any organization seeking to foster such an approach to reading, is cultivating a mindset that facilitates strategic thinking. Clausewitz’s paradoxical trinity is helpful because he made clear that the military is not an isolated entity in war. War is a complex and societal activity. Thus, the military professional must explore as many of the aspects as possible when studying the nature of war. The very act of exploring and learning should be an exciting enterprise, which is its own reward. SAMS cultivates this exploratory mindset, but it requires more than just a booklist. The faculty facilitates discussions so students can make the connections themselves. They push students beyond the comfort zone of narrowly focusing on leadership and training. The US Army would benefit if more organizations, both in professional military education and in the operating force, took this approach with their leader development programs.

No comments:

Post a Comment