The Pegasus Project affair brings back to the headlines Israel’s glorious status as the leader in cyber technology and champion of intelligence gathering. But the line separating glory from ignominy is often blurred and fragile in the Middle East. Israel is the region’s “cyber queen” and is ranked among the world’s top cyber powers. It is also considered a global “intelligence silo” based on the capabilities of the Mossad, the unbelievably creative technologies of the military’s famed unit 8200 and its national cyber expertise. Still, as we saw this week, things could get complicated.

Israel, as all of its allies know, leverages its intelligence assets in order to forge alliances and establish relations, security cooperation and even peace agreements. It not only shares intelligence with other countries (bar information damaging to its own interests), but it also helps other regimes and leaks tips and reports potentially helpful to various leaders. In Jordan’s case (according to reports in past years), it has helped the Hashemite family thwart assassination and other subversive plots against the monarchy.

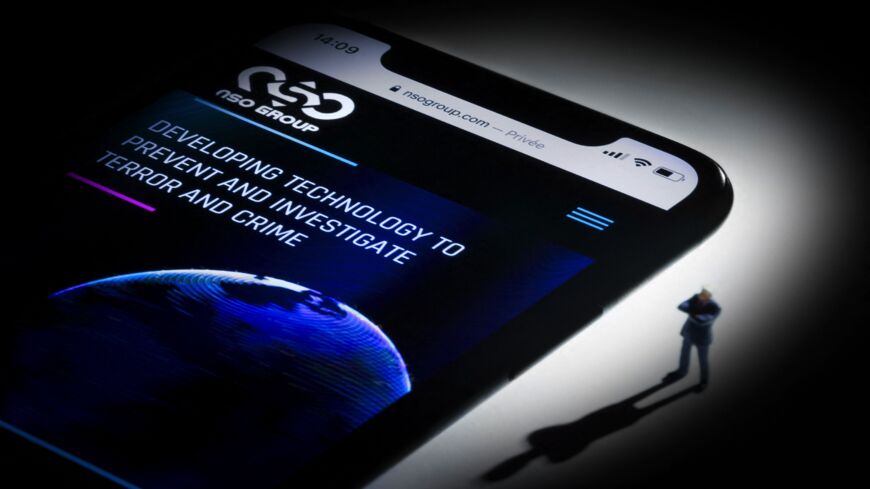

The new era offers a particularly powerful intelligence tool: cyber power. Senior Israeli cyber experts believe that distinct government footprints underpin the scandal rocking world capitals in recent days that involves the use of the Israeli spyware Pegasus, which was developed by Israel’s NSO cyber company. According to these experts, Israel leverages its cyber capacity and “traded” spyware tools, among them NSO’s Pegasus, with other countries in the Middle East.

A source in Israel’s cyber industry told Al-Monitor on condition of anonymity that former Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and his close associate, former Mossad director Yossi Cohen, “met with Middle Eastern leaders and hinted that they would permit them to buy the best attack cyber ware that Israel had to offer as a special ‘bonus’ for establishing full diplomatic relations with Israel.” The issue of Israel’s responsibility for abuse of these cyber tools by other states will undoubtedly feature prominently in discussions around the world.

For now, this boomerang has turned around and struck Defense Ministry headquarters in Tel Aviv with full force. French President Emmanuel Macron, for example, intends to demand explanations from Israel about the inclusion of his name on a list of 50,000 leaked phone numbers of leaders, officials, journalists and activists exposed in an international investigative journalism project that unveiled the use of Pegasus by various governments.

NSO co-founder and head Shalev Hulio adamantly denies claims in the expose about his company’s involvement in compiling the list of names, insisting NSO operates with full transparency, sells only to governments approved by Israel for use against criminals and terrorists, and rejects out of hand all accusations against the firm.

“This is the tip of the iceberg regarding the use of Israeli technologies for the benefit of such acts,” said Mickey Gitzin, executive director of the New Israel Fund, a social justice and human rights group. “Many of the technologies need the approval of the Defense Ministry, and the level of regulation in the area in Israel is almost zero.”

Media reports quote Amnesty International officials as saying that while the human rights organization views NSO as responsible for the abuse of its products, it is not solely responsible. Most of the responsibility, these sources argue, rests with the Israeli Defense Ministry’s export licensing authorities. Although these authorities are diligent and serious in their oversight, more stringent legislation is required to prevent attack cyber tools and Israeli weapons from reaching human rights violators, they contend.

“Clearly, their (NSO) actions pose larger questions about the wholesale lack of regulation that has created a wild west of rampant abusive targeting of activists and journalists. Until this company and the industry as a whole can show it is capable of respecting human rights, there must be an immediate moratorium on the export, sale, transfer and use of surveillance technology,” stated Amnesty.

Has the flourishing NSO cyber firm entangled itself and, worse, dragged Israel into a vortex of investigations and lawsuits around the world? That remains to be seen. Similar claims against the company’s spyware surfaced in 2018 following the murder of Saudi dissident journalist Jamal Khashoggi but failed to take off. Can a cyber developer be held to account for the use of its attack spyware by a state that bought it? Regulation of this issue is still in its infancy and the answer rests in a twilight zone, for now.

NSO director Hulio told Al-Monitor this week that his company only sells its software to governments, not to private groups, and had made a decision not to sell to just any country. “Some governments are not worthy of having such tools. We work with 45 states and refuse to work with 90 others. … The expose was amateurish; we have no connection with the list of phone numbers that was published and the media outlets that ran the list don’t know who compiled it. NSO does not have and will not have a bank of targets.”

Hulio added that unlike weapons, over which a seller has no responsibility once they are sold, “We have mechanisms that ensure that if a government abuses the software it bought, we can know it. Therefore, there are governments to which we sold in the past and found abuse, and we shut down their system. This is all written in a special transparency report we issued.”

Officially, Israel is trying to stay out of the fracas, but several closed-door discussions with multiple attendants have already been held, some in the office of Defense Minister Benny Gantz. The Israeli response will be determined by the extent of the crisis and depth of NSO’s and its own entanglement, should it arise. The Defense Ministry has a well-oiled supervision mechanism to oversee all defense-related exports. The problem is that by the same token that Israel finds it very hard to follow the use of every machine gun or rocket it sells to other countries, surveillance spyware or attack cyber ware is very hard to track.

“Everyone spies on everyone,” a senior Israeli security source told Al-Monitor on condition of anonymity. “In the past it was done by planting listening devices, then things moved to fiber optics and satellites, and today spyware planted in mobile phones is popular. It always existed; it always will. The principle is established. The only difference are the means used.”

No comments:

Post a Comment