Hilal Khashan

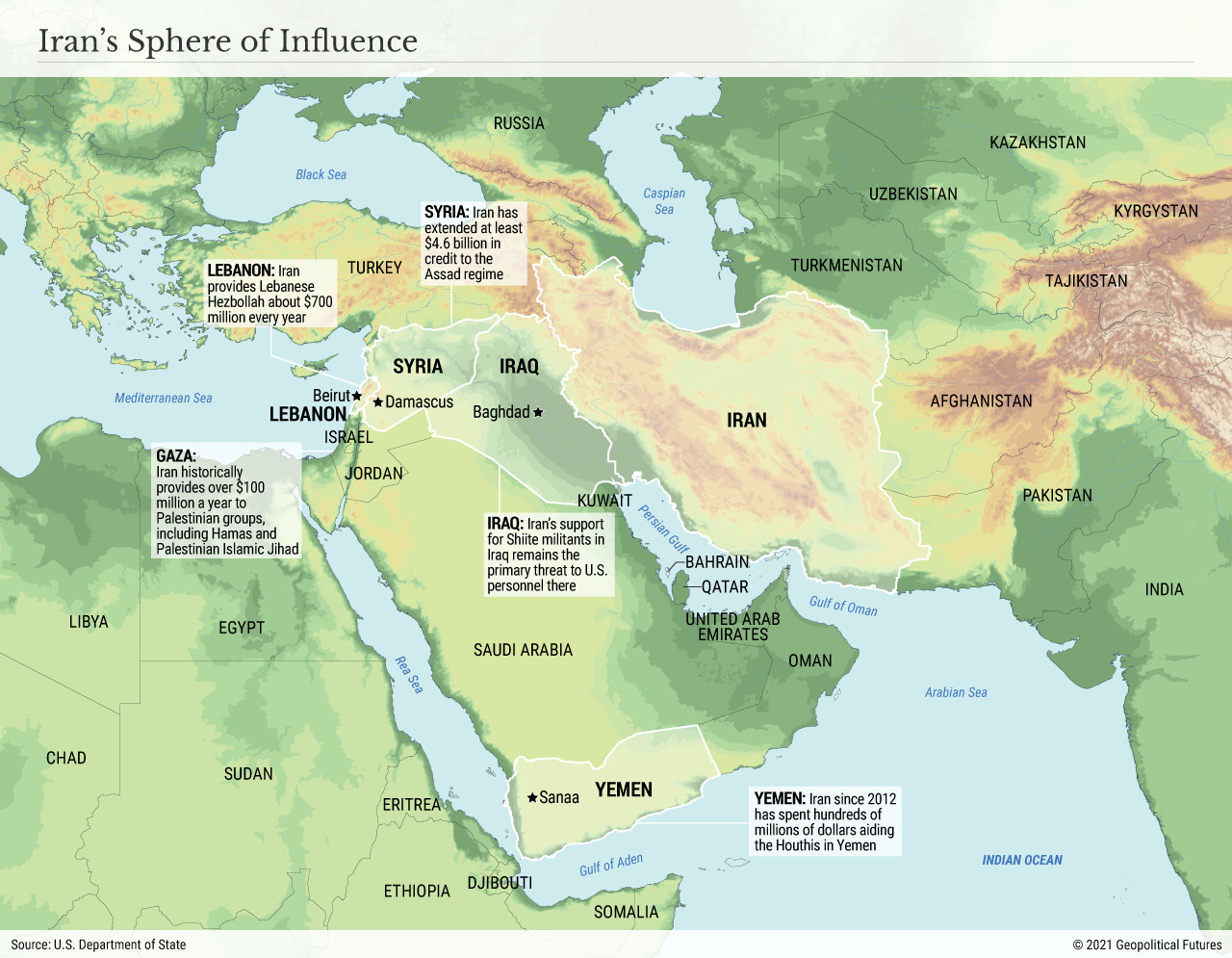

Iran presents itself to the outside world as the mighty Islamic Republic, built on strength, perseverance and independence. But in reality, Iran is a weak country. Its military hardware is obsolete, and its economy is hurting. It became a regional power only by default following Iraq’s loss in the 1991 Gulf War and the subsequent crippling blockade. The uprisings that shattered several Arab countries didn’t affect Iran, which then gained a modicum of power and influence in the region, despite its internal weakness. Iran thus succeeded in transforming its mediocre capabilities into assets in a turbulent Middle East, but this should not be confused with real strength. (click to enlarge)

Empty Rhetoric

Iranian officials often issue fiery statements against the West threatening violence and retribution for any moves targeting Tehran. A former commander of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, for example, threatened to level Tel Aviv and Haifa if Israel attacked Iran. In 2018, the IRGC’s commander-in-chief promised to annihilate Israel, saying, “If there is war, the result will be your destruction.” That same year, the head of the Iranian army predicted that Israel would disappear in 25 years. Former Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad also threatened to wipe Israel off the map.

But despite their aggressive rhetoric, the Iranians know that acting on their threats could provoke a response they’d rather avoid. Ayatollah Ali Khamenei described the killing of Qassem Soleimani, the commander of the IRGC’s Quds Force, by a U.S. drone in 2020 as a declaration of war and promised to have no mercy on his killers. But Iran’s retaliation – hitting two Iraqi bases housing U.S. troops and having its proxy Popular Mobilization Forces fire rockets at a military base near Baghdad – was a feeble response to the murder of the second-most powerful person in the country.

Indeed, Iran’s leadership understands the rules of the game, and it abides by them. It knows that U.S. President Joe Biden does not want war or regime change in Tehran. Former President Donald Trump committed to withdrawing U.S. troops from the Middle East and, in 2020, ordered that the number of soldiers stationed in Iraq be slashed by one-third.

The Iranians, meanwhile, have also learned lessons from past experience. In 1988, the USS Samuel B. Roberts frigate hit a naval mine laid by Iran in the Persian Gulf during the Tanker War. The U.S. then launched Operation Praying Mantis, which sank six Iranian ships and destroyed two oil rigs. In 2019, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu bragged about the Israeli Air Force’s ability to reach any target in Iran, which could not respond in kind. A year earlier, three Israeli F-35 fighter jets flew over Tehran and returned safely to base. Israel launched hundreds of airstrikes on Iranian convoys loaded with weapons for Hezbollah, and neither Iran nor Hezbollah dared to fight back. Last month, a former Iranian intelligence minister admitted that Israel’s Mossad intelligence agency has penetrated Iran and is increasing its influence, especially among Iran’s minority groups. Israel’s assassination last November of Mohsen Fakhrizadeh, known as the father of Iran’s nuclear program, revealed the extent of Iran’s vulnerability to Israeli subversion.

Hungry for Recognition

In 2014, when the U.S. assembled a coalition to try to oust the Islamic State from Mosul, Iraq’s second-largest city, Iran wanted to join it, in part to reduce its global isolation and in part to deflect attention from its nuclear program. The U.S., however, preferred to engage instead with Iran’s proxy group, the Iraq-based Popular Mobilization Forces.

For the anti-IS coalition, there was little direct collaboration with Iran. The U.S. Air Force provided support to an offensive that included Iraqi army troops, peshmergas and PMF units to oust IS from Amerli, a Shiite Turkmen town in northern Iraq some 100 kilometers (60 miles) from Iran’s border. But for the most part, the U.S. opposed Iran’s involvement. Washington’s view was that both the Islamic State and Iran presented serious threats. Its opposition drove Iran to denounce U.S. military action in Syria and Iraq as a violation of their national sovereignty and international law.

Iran claims it defeated IS and other radical Islamic movements in Syria and Iraq. But in Syria, government forces and their Iranian allies were on the defensive until 2015, when the Russian air force joined the fighting. And in Iraq, the decisive factors in the Islamic State’s defeat were the U.S. Air Force and the Kurdish troops on the ground.

Contrary to official claims, Iran is eager for Israeli recognition as an equal regional power. Israel, however, prefers to negotiate peace treaties with Arab countries, not Iran, which had no role in the Arab-Israeli conflict and recognized Israel as a de facto entity in 1950.

To make itself appear more powerful, Iran grossly exaggerates the value of its weapons industry. In 2007, it introduced a copy of the 1950s Northrop F-5 fighter, and in 2014, it replicated a U.S. RQ-170 drone that landed in Iranian territory in 2011. Aviation experts say the Iranian version is nothing more than a propaganda tool. Similar doubts shroud Iran’s Qaher 313, allegedly a fifth-generation stealth plane that looks more like a replica of the F-313 trainer.

Weak Retaliation

Despite their bombastic rhetoric, Iran and its allies regularly fail to retaliate against attacks on their personnel and assets. When Israel killed top Hezbollah military commander Imad Mughniyeh in 2008, Hezbollah chief Hassan Nasrallah said he would destroy the Israeli army, but of course that never happened. Similarly, the PMF condemned last month’s U.S. airstrikes against its bases in the Iraqi-Syrian border area but refrained from retaliating.

For the past two years, Israel has been attacking Iranian ships transporting strategic supplies for the Syrian regime and Houthi rebels in Yemen. Iran calibrates its reaction to avoid casualties or severe damage to Israeli ships. Iran has been exceptionally keen on not sliding into a full-scale war with the U.S. or Israel, cleverly using Iraq’s PMF and Yemen’s Houthis to wage asymmetric attacks on its behalf.

The PMF use unguided rockets and drones against U.S. bases in Iraq to avoid inflicting casualties and provoking retaliation. When firing rockets at the vast U.S. Embassy in Baghdad or military bases housing U.S. troops, the PMF makes sure they land outside the perimeter of the facilities. These attacks are a means of communication, not a serious attempt to inflict harm.

Meanwhile, U.S. sanctions on Iranian oil exports have severely hurt its already weak economy. Iran’s oil exports dropped from 2.8 million barrels per day in 2018 to 300,000 barrels per day in 2020. (They rose recently to 750,000 barrels per day.) Iran responded cautiously by attacking Saudi and Emirati oil tankers in the Persian Gulf because it knows that they would not retaliate, unlike the U.S. and Israel. The Houthis continue to launch frequent attacks on air bases and other military and infrastructure facilities in southwest Saudi Arabia. Members of the PMF in southern Iraq attacked oil facilities in Saudi Arabia’s Eastern Province in 2019. The Saudis do not respond to provocations from Iraq, and their airstrikes against the Houthis have not affected the Houthis’ control over most of Yemen.

Iran is a country engulfed in economic problems ranging from deep-seated corruption to debilitating U.S. sanctions to economic domination by religious institutions and IRGC-affiliated companies. Its conservative clerics and senior commanding officers have put up a facade of military prowess that has been less than convincing for critically minded Iranians. Still, the regime in Tehran remains secure, despite the occasional protest. The ruling elite seem convinced that Iran has a bright future ahead, while the reformists face an uphill battle to secularize the country.

No comments:

Post a Comment