Source Link

China’s global outbound investment hit a 13-year low in 2020: Concerns that the Covid-19 global pandemic slump might trigger another round of Chinese distressed asset-buying proved unfounded. Instead, China’s global outbound M&A activity dropped to a 13-year low, as completed merger and acquisition (M&A) transactions totaled just EUR 25 billion, down 45 percent from 2019.

China’s global outbound investment hit a 13-year low in 2020: Concerns that the Covid-19 global pandemic slump might trigger another round of Chinese distressed asset-buying proved unfounded. Instead, China’s global outbound M&A activity dropped to a 13-year low, as completed merger and acquisition (M&A) transactions totaled just EUR 25 billion, down 45 percent from 2019.

Executive summary

China’s global outbound investment hit a 13-year low in 2020: Concerns that the Covid-19 global pandemic slump might trigger another round of Chinese distressed asset-buying proved unfounded. Instead, China’s global outbound M&A activity dropped to a 13-year low, as completed merger and acquisition (M&A) transactions totaled just EUR 25 billion, down 45 percent from 2019.

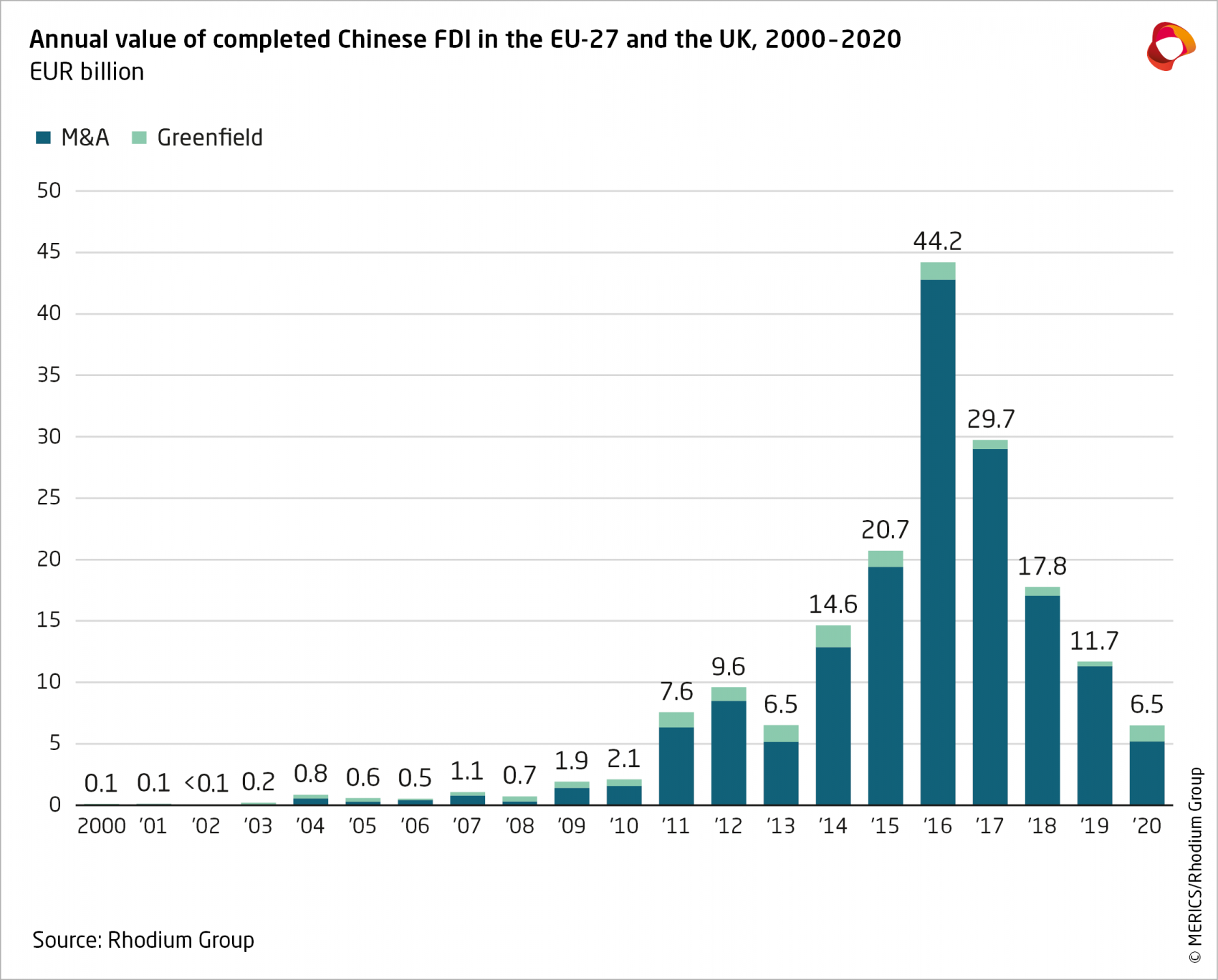

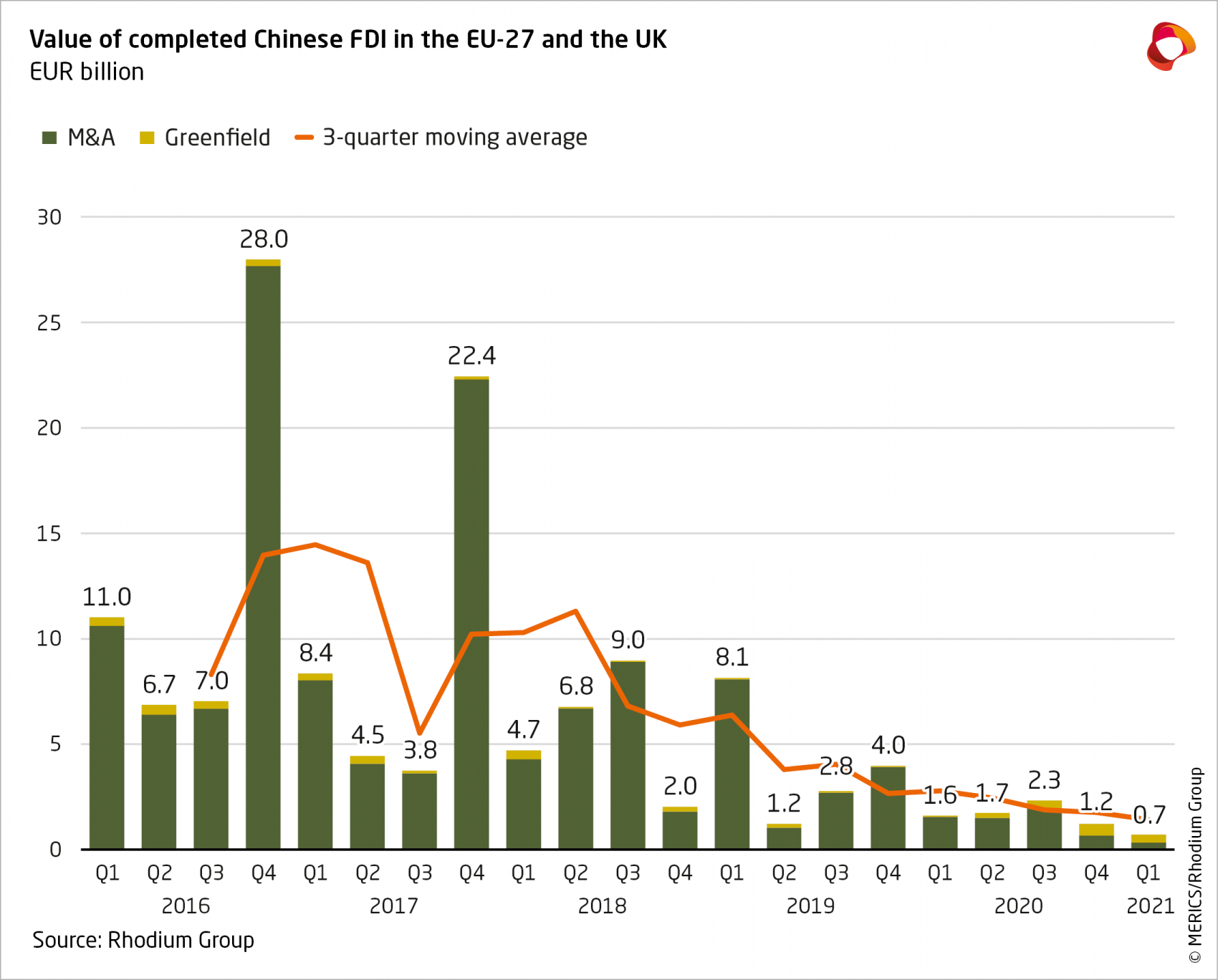

China’s global outbound investment hit a 13-year low in 2020: Concerns that the Covid-19 global pandemic slump might trigger another round of Chinese distressed asset-buying proved unfounded. Instead, China’s global outbound M&A activity dropped to a 13-year low, as completed merger and acquisition (M&A) transactions totaled just EUR 25 billion, down 45 percent from 2019.China’s FDI in Europe continued to fall, to a 10-year low: Shrinking M&A activity meant the EU-27 and the United Kingdom saw a 45 percent decline in completed Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) last year, down to EUR 6.5 billion from EUR 11.7 billion in 2019, taking investment in Europe to a 10-year low. However, greenfield Chinese investment reached its highest level since 2016 at nearly EUR 1.3 billion.

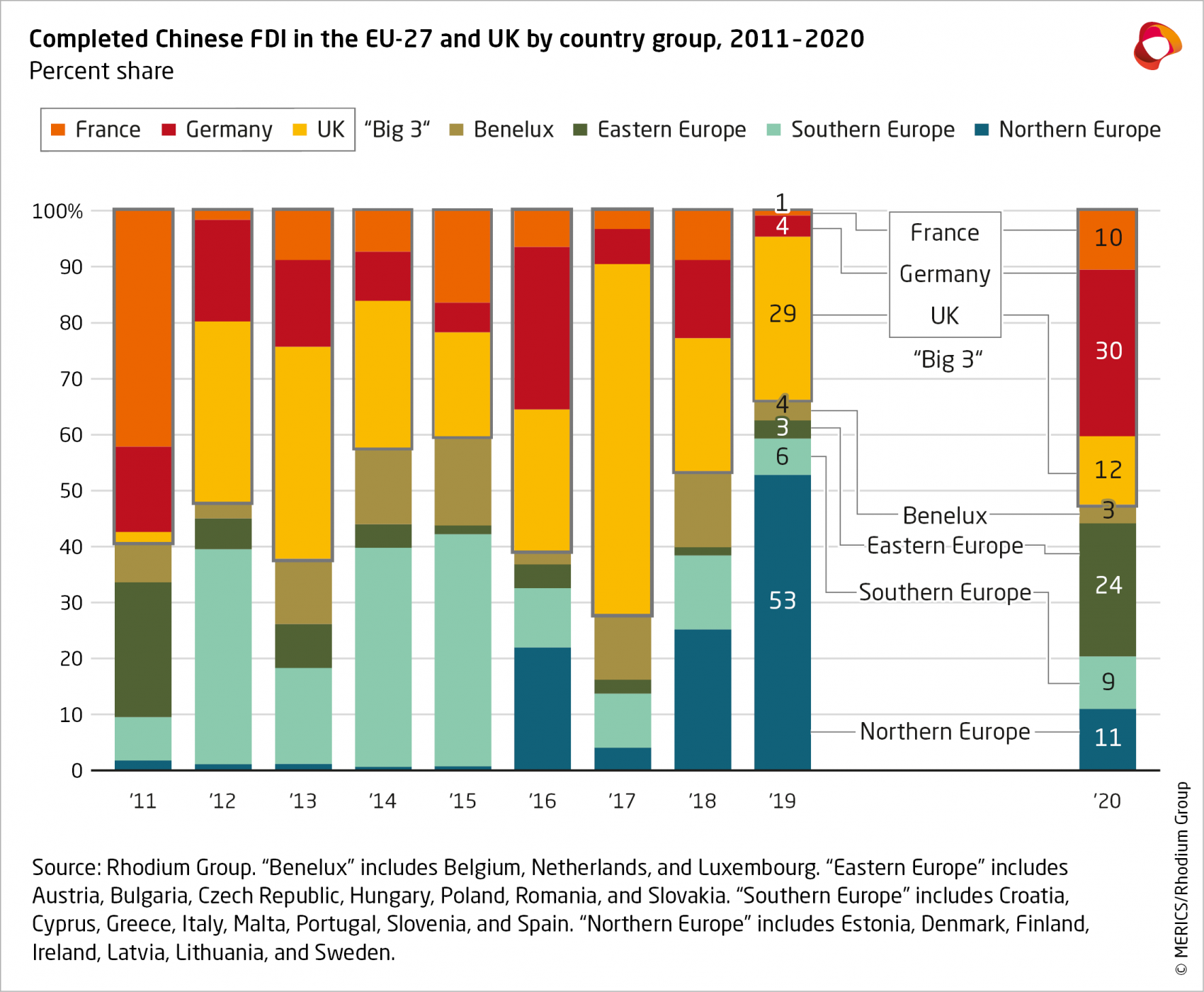

The “Big-3” reclaimed their top spot, Poland emerged as a key recipient: More than half of total Chinese investment in Europe went to the “Big Three” economies – Germany, the UK and France. However, the UK saw Chinese investment plummet by 77 percent. Poland rose to become the second most popular destination, though inflows of EUR 815 million were largely concentrated on one acquisition.

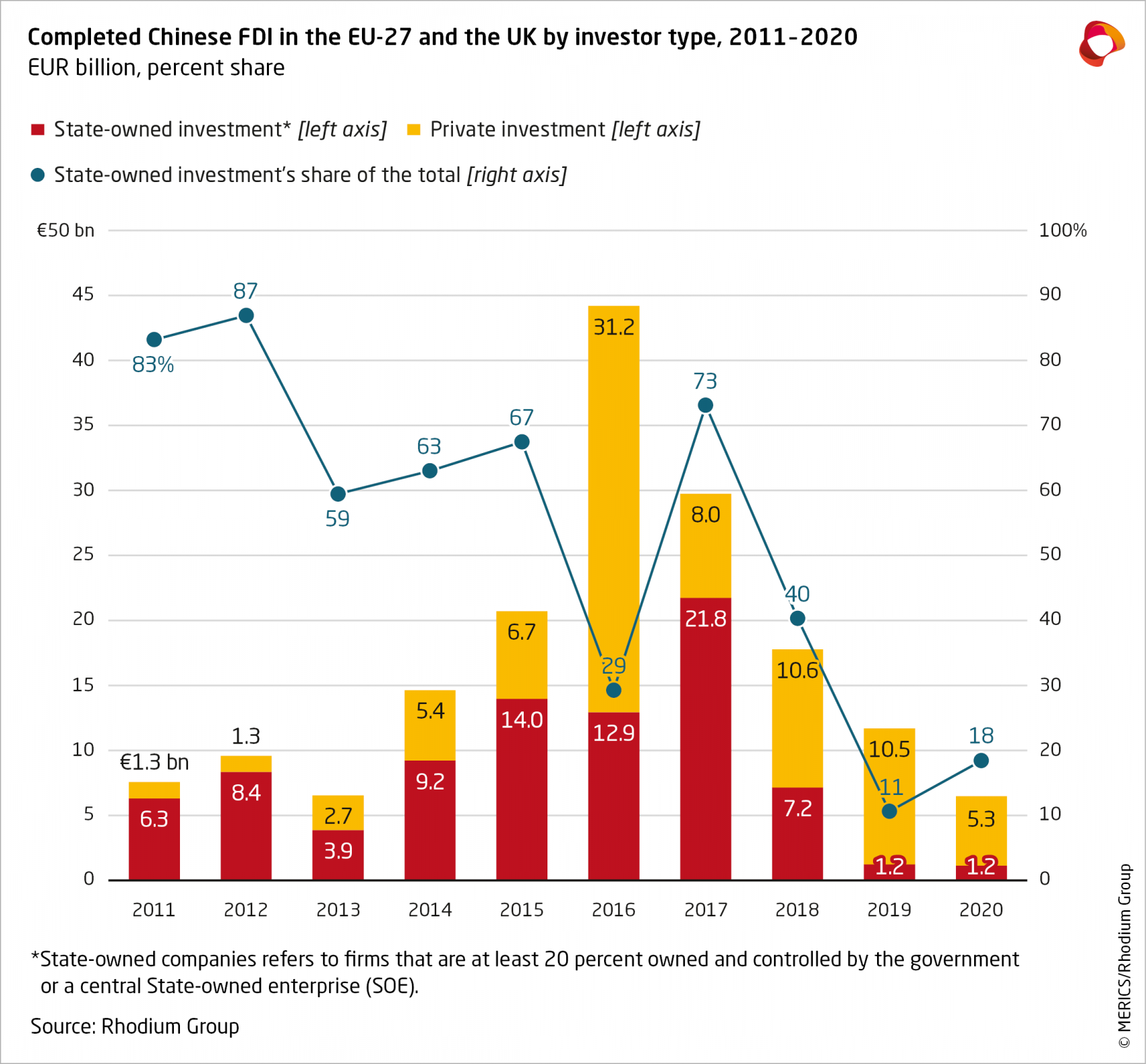

China’s state-owned enterprises (SOEs) took a higher share in a quiet market: SOEs were responsible for 18 percent of total Chinese FDI to Europe, higher than 11 percent 2019 but still significantly below historical averages. Their investment stayed relatively stable in absolute terms, however, concentrating in energy, infrastructure and basic materials. Private sector investment dropped by almost 50 percent.

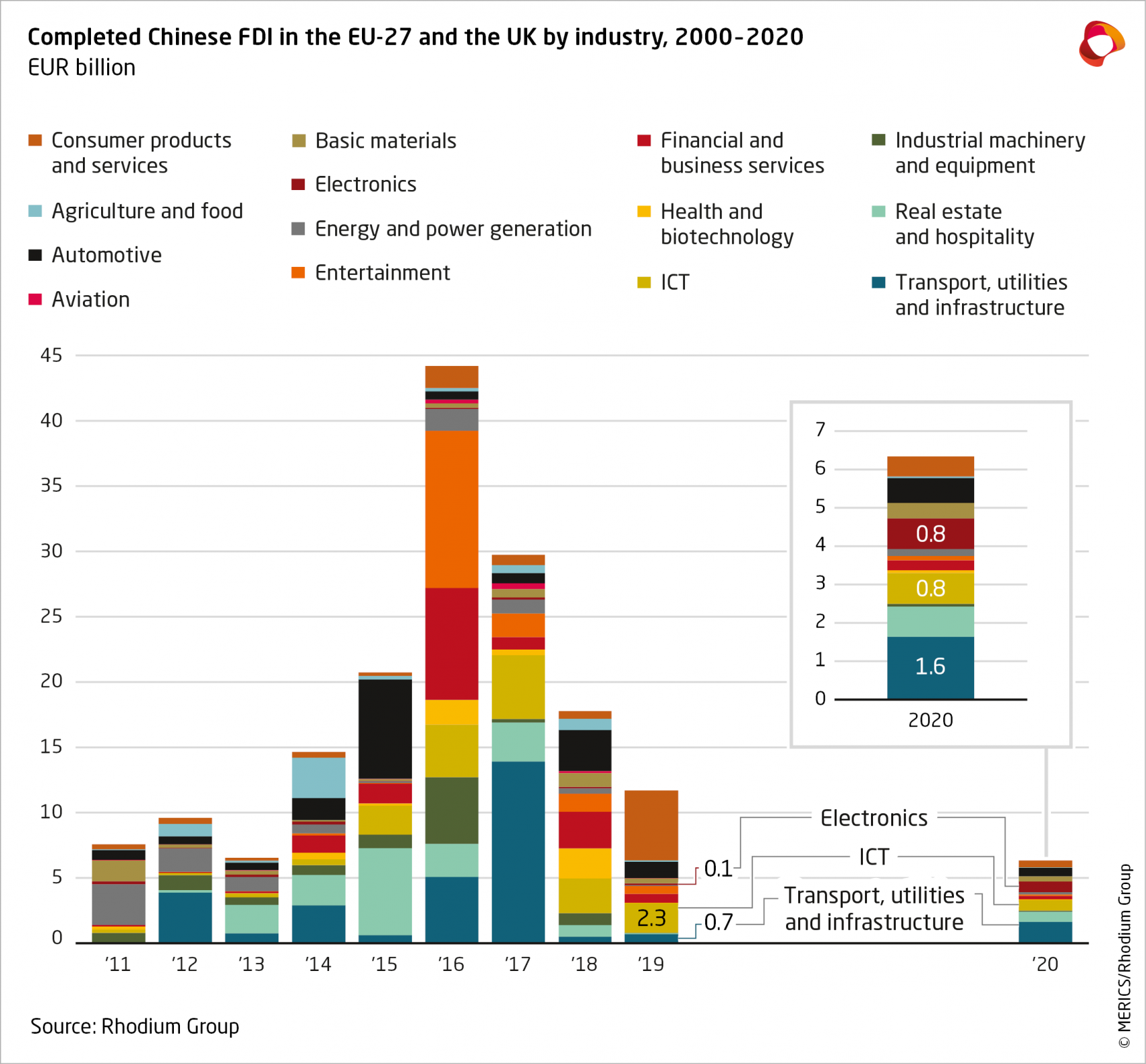

Chinese investment was spread more evenly across sectors: Small- and mid- size transactions dominated in 2020, with no major billion-dollar acquisitions as in 2019. As a result, Chinese investment was spread more evenly across sectors. Infrastructure, ICT and electronics were the top three sectors, attracting 51 percent of the total.

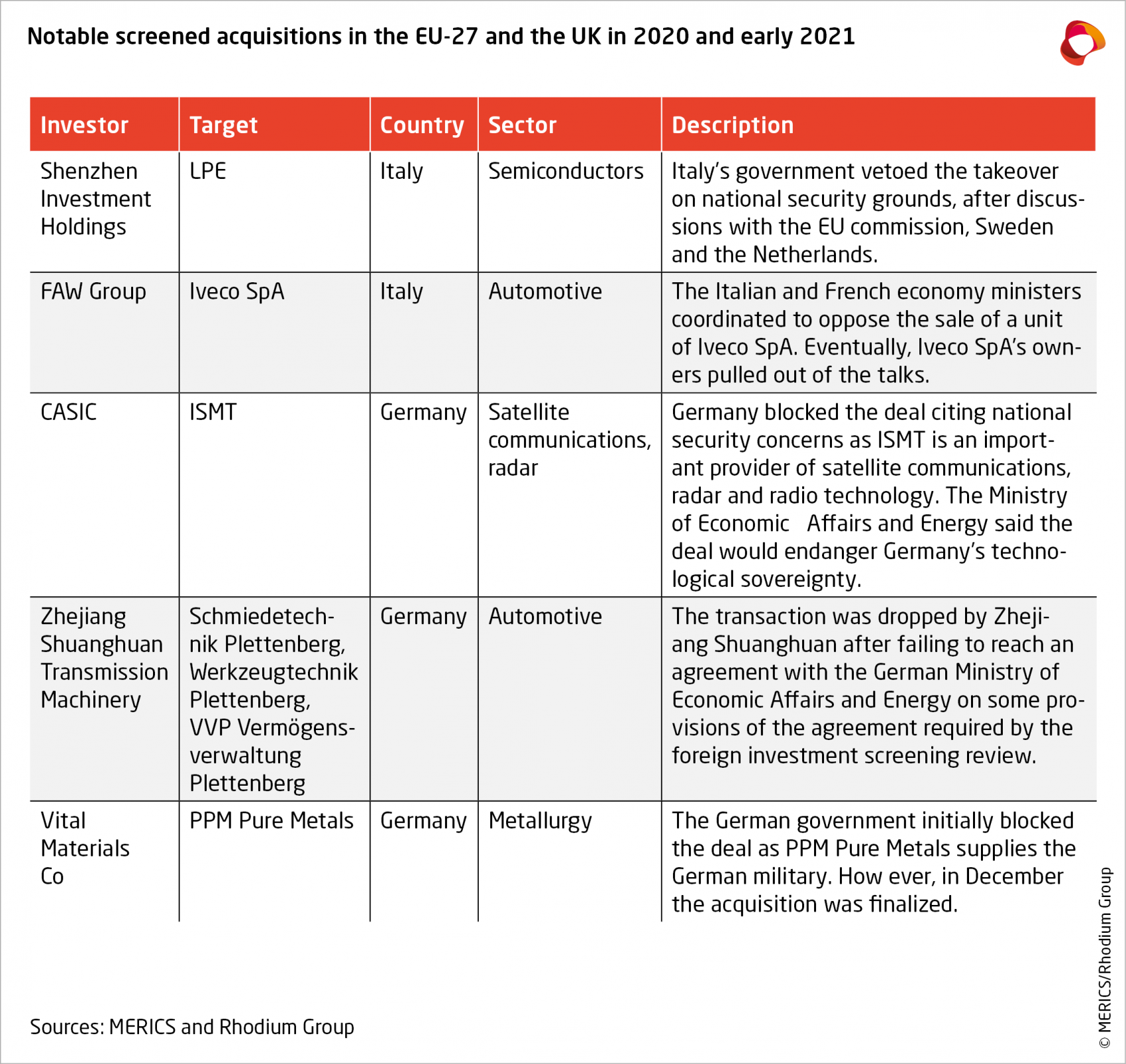

Chinese FDI faces greater scrutiny by EU member states: The Covid-19 crisis prompted the EU to issue guidelines stepping up scrutiny of FDI in Europe’s critical assets. 14 EU member states, including Italy, France, Poland and Hungary, have updated their FDI screening mechanisms last year. Member states have also moved to block several acquisitions by Chinese firms.

Headwinds to Chinese investment in Europe will grow in 2021: Chinese FDI activity into Europe continued to fall in the first quarter of 2021 and has remained weak elsewhere, even as global M&A activity has recovered and surged to a 10- year high of EUR 1.08 trillion. Europe remains an attractive investment location. However, continued disruption from Covid-19, high barriers to outward capital flows in China and rising regulatory barriers to foreign investment in Europe have all contributed to low levels of Chinese investments. Deteriorating EU-China relations will create additional headwinds for Chinese investors going forward.

1. Introduction

The Covid-19 pandemic triggered major global disruptions in business as well as societal activity. Foreign direct investment (FDI) was no exception. As travel restrictions halted ongoing and new deal-making, global FDI volumes plunged by 38 percent in 2020 set against the previous year, according to the OECD. It was the lowest level for global FDI activity since 2005.

Fears emerged in Europe (and elsewhere) that Chinese investors might engage in distressed asset buying, taking advantage of depressed equity values worldwide as the pandemic pushed countless countries into recession. However, there was no sign of an opportunistic buying spree. Instead, global investment activities by Chinese firms declined in 2020.

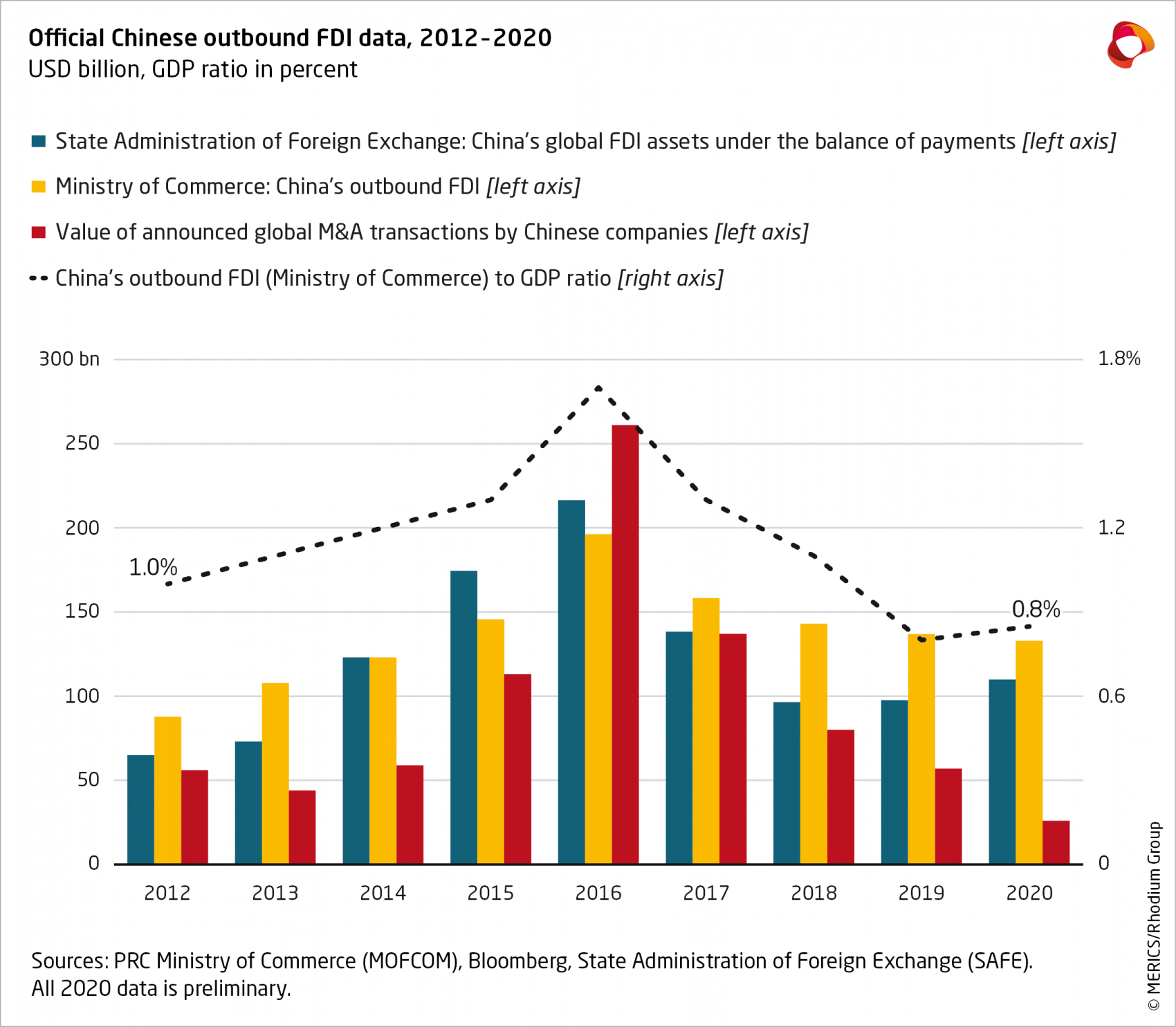

Official Chinese statistics show stable outbound investment at USD 132.9 billion (EUR 116.5 billion), likely boosted by intra-company flows and arbitrage. However, transaction-level data paints a different picture. According to our calculation, China’s global outbound M&A activity slipped to a 13-year low in 2020; completed deals totaled just EUR 25 billion, down from EUR 47 billion in 2019, a drop of 45 percent.

Exhibit 1

China’s overseas investment activity has been declining each year since 2016, due to domestic constraints on outbound capital flows and tighter scrutiny of Chinese investments abroad. The Covid-19 pandemic accentuated the fall in China’s outbound activity by hindering normal business activity.

This report summarizes China’s investment footprint in the EU-27 and the United Kingdom (UK) in 2020, analysing the fallout from the pandemic as well as policy developments in Europe and China. The research builds on the long-standing collaboration between Rhodium Group and MERICS.

2. Chinese FDI in Europe: 2020 Trends

2.1 Pandemic pushes Chinese FDI in the EU and the UK to its lowest value since 2010

As a result of the pandemic, completed Chinese FDI in the EU-27 and the UK fell to EUR 6.5 billion in 2020, from EUR 11.7 billion the previous year (Exhibit 2). Faced with a mix of travel restrictions and changed domestic economic circumstances, some Chinese investors decided against completing large transactions. For example, the giant automaker FAW Group discontinued talks to acquire Italian truck maker Iveco for EUR 2.6 billion, and Bank of China walked away from its EUR 132 million purchase of Ireland-based Goodbody Stockbrokers.

Exhibit 2

In both cases, the Chinese side cited Covid-19 related uncertainty. However, the pandemic was not the only force at work. Persistent outbound capital controls in China, heightened regulatory scrutiny of Chinese investments in Europe and deteriorating public sentiment towards China also created headwinds.

Diminished M&A activity pulled down total investment. However, Chinese greenfield investment jumped to its highest level since 2016, at nearly EUR 1.3 billion or 20 percent of total FDI, compared to an average of 6.5 percent over the past decade. Among the most notable greenfield investors were technology firms such as Huawei, Lenovo, and ByteDance, as well as consumer goods-makers Haier and Hisense. The most eye-catching of the large multi-year greenfield projects announced last year were SVolt Energy Technology’s EUR 2.1 billion battery plant in Germany to gear up for e-vehicles; telecoms giant Huawei’s EUR 1 billion investment on an R&D center in the United Kingdom; and a EUR 438 million deal to build data centers in Ireland for ByteDance subsidiary TikTok.

2.2 Germany is top destination for Chinese capital; interest in Poland grows

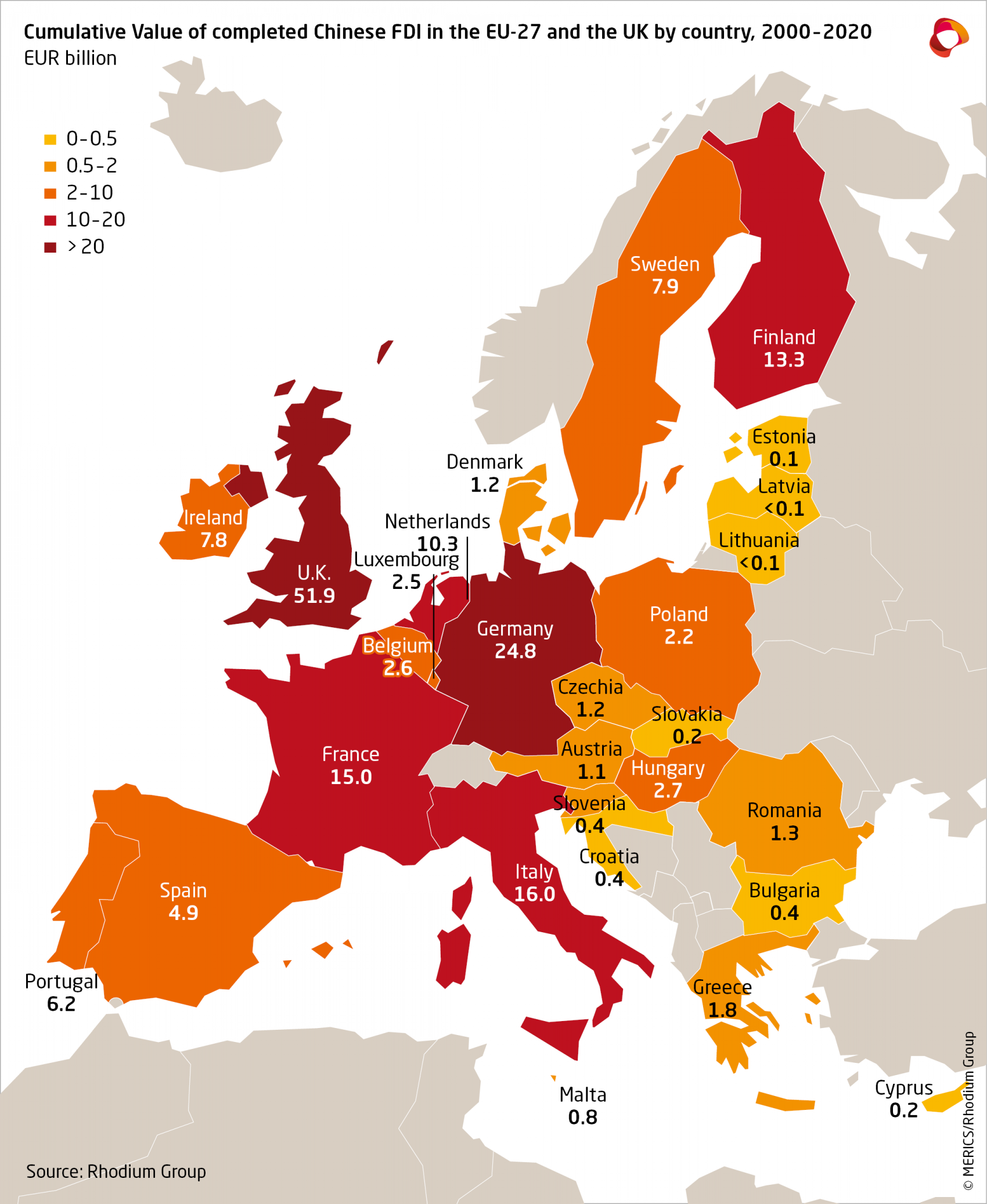

The “Big Three” European economies were back as the main destination for Chinese investment in 2020, receiving more than half of the total, or 53 percent (see Exhibit 3), which was a return to normal patterns after high levels of deal-making in the Northern Europe region (the Baltic states, Scandinavia and Ireland) the previous year.

Exhibit 3

Germany was by far the largest recipient of Chinese investment, most of which consisted of relatively small transactions. The UK, which ranked third overall, recorded a drop of 77 percent in inbound Chinese investment – the lowest level in nearly ten years.

Poland rose up the rankings to second overall as it attracted a record EUR 815 million in Chinese investment, much of it due to Poland’s share of GLP’s acquisition of the Goodman Group’s Eastern Europe logistics portfolio. The deal pushed the Eastern Europe region up to become the second preferred destination for Chinese investors in 2020, attracting a total of EUR 1.5 billion.

Exhibit 4

Investment in the rest of Europe was more evenly split, due to the small average size of transactions. Northern Europe’s share of China’s investment slumped from 53 percent in 2019 to 11 percent in 2020 (at EUR 703 million). Some major transactions occurred in the region including Evergrande’s acquisition of the remaining shares in Swedish electric vehicle-maker NEVS AB for EUR 333 million. Southern Europe and the Benelux countries both saw slight gains in their share of China’s FDI, as Southern Europe got 9.4 percent (EUR 598 million) and Benelux region attracted 3.3 percent (EUR 213 million).

2.3 Investment by China's state-owned companies remains at a 10-year-low

Historically, China’s state-owned enterprises (SOE) constituted the bulk of Chinese investment in Europe, averaging more than 70 percent of total investment between 2010 and 2015. The private sector’s share started to rise from 2014, helped by the liberalization of China’s outward FDI (OFDI) regime. Administrative controls were loosened and incentives for firms to invest overseas increased. By 2019, European investments by SOEs had fallen to 11 percent of total Chinese investment.

In 2020, SOE investment remained steady in absolute terms at EUR 1.2 billion (see Exhibit 5). However, private sector investment plummeted 49 percent to EUR 5.3 billion, so SOEs ended up with a bigger share – 18 percent – of the total. Increased scrutiny of Chinese state-owned investments in Europe has not impeded Chinese SOEs from making major acquisitions in the European transport, energy and infrastructure sectors. China Three Gorges bought an additional stake in Portuguese energy provider EDP for EUR 229 million. China Railway Construction Corp (CRRC) purchased Spanish construction company Aldesa for EUR 242 million. And CRRC Zhuzhou acquired German rail firm Vossloh Locomotive for EUR 44 million.

Exhibit 5

2.4 Chinese investment was more evenly spread between sectors though infrastructure and ICT remained top targets

Chinese investment in Europe was more diverse in 2020 than the previous year, when more than 70 percent of it went into consumer products and services and ICT. The more even distribution profile was due mainly to the smaller average size of Chinese investments.

In 2020, the top target was the transportation, construction, and infrastructure sector, with 25 percent of the total (see Exhibit 6). The largest transaction was GLP’s acquisition of the Goodman Group’s warehouse portfolio in Central and Eastern Europe; it included transactions in Poland, Slovakia, Hungary, and the Czech Republic totaling roughly 1 billion EUR. Other high-value investments included CRCC’s EUR 243 million acquisition of construction firm Aldesa and China Three Gorges’ EUR 229 million purchase of an additional stake in energy provider EDP.

Nonetheless, the ICT sector remained popular, attracting 18 percent of the total. The striking feature of in 2020 was how much ICT investment was channeled into greenfield purchases; major examples include the already mentioned Huawei R&D centers in the UK and Hungary, and ByteDance’s TikTok data center in Ireland.

Electronics was the third largest sector by investment value. Transactions included: Universal Scientific Industrial’s acquisition of French Asteelflash Group (EUR 395 million), and Jiangsu Riying Electronics’ acquisition of Elektromechanische Schaltsensoren EMS GmbH in Germany (EUR 171 million).

Exhibit 6

3. Outlook

Global M&A activity (pending and completed) climbed back to EUR 1.08 trillion (USD 1.3 trillion) in the first quarter of 2021, a ten-year record. The jump was fueled by the broadening global economic recovery and low cost of capital due to stimulus measures deployed by governments worldwide.

However, China’s outward investment remained depressed. China’s global outbound M&A activity was hovering at 2020 levels in the first quarter of this year; monthly transaction counts remained low, at approximately 20 single deals. Within the EU-27 and UK, the value of completed Chinese FDI transactions continued to drop in the first quarter, dipping to one of the lowest quarterly amounts in at least a decade (EUR 707 million) (see Exhibit 7).

In March, there was a bounce in announced Chinese FDI into the EU (as opposed to pending or completed) to EUR 4.6 billion, compared to EUR 155 million in January and EUR 708 million in February. Most of it was accounted for by one single deal: Hillhouse Capital’s EUR 3.7 billion upcoming acquisition of Philips’ domestic appliances business.

Exhibit 7

Low investment levels in early 2021 reflected several factors, all of them likely to persist through the year:

Beijing’s strict capital controls continue to constrain Chinese FDI, despite the swift economic recovery. China’s government has retained its strong hold on capital outflows, unmoved by such positives as China’s rapid and broadly healthy economic recovery from the pandemic slump which brought strong inbound capital inflows to China in late 2020 and Q1 2021. This scenario could have given Beijing confidence to lift some of the current barriers to outward FDI. However, it has limited itself to lifting restrictions only carefully and in minor ways. For example, quotas for outward portfolio investments through the QDII (Qualified Domestic Institutional Investors) were marginally increased; the scope of the Southbound Hong Kong Connect Mechanisms which allow foreign investors to trade eligible mainland-listed stocks through Hong Kong was expanded. But few steps were taken that could bolster outward FDI. And most regulatory changes aimed to facilitate inflows rather than outflows. Many outward investors are also constrained in their access to capital, as Beijing has shifted its policy priorities away from stimulus to deleveraging and financial risk management.

The EU has tightened investment screening of Chinese investors. The EU FDI screening framework became fully operational in 2020. Investment screening regimes have been re- viewed by 14 EU countries, including France and Italy, since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic. Others, including Germany, are still finetuning theirs. In January, the German government announced plans to broaden investment screening rules to cover high-tech sectors including AI, semiconductors, autonomous driving and aerospace. In the short-term, new investment screening rules and their implementation may create some uncertainty for foreign investors, until a track record of implementation emerges. Transactions in sensitive sectors are more likely to be reviewed and potentially blocked (see Exhibit 8). However, transparent and consistent screening rules can help reduce uncertainty in the long run and limit the politicization surrounding certain transactions. The approval of CRRC Zhuzhou’s acquisition of Vossloh, despite strong public debate, is a case in point.

Exhibit 8

In addition to FDI screening, Brussels is upgrading defensive measures against perceived distortions from China that affect the EU single market. Some of these measures could raise barriers for Chinese investments in the next 12 to 18 months. The EU Commission published a proposal on May 5, 2021, for an instrument on foreign subsidies that would give it powers to review and block foreign investments that benefit from foreign subsidies. The EU has also resumed work on the International Procurement Instrument (IPI), which could limit the participation of Chinese firms in the EU’s public procurement markets if European firms face restrictions to participate in Chinese public tenders.

As EU-China relations enter a new phase, the greatest risk to China’s FDI into Europe is the souring political relationship. In March, following EU sanctions against Chinese officials and public entities for alleged human rights abuses in Xinjiang, Beijing retaliated with its own sanctions against EU individuals (including MEPs of all major political factions and individual researchers) and research organizations (including MERICS). China’s tit-for-tat sanctions led MEPs to pass a motion on May 20, 2021, to freeze parliamentary ratification of the EU-China Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI) unless sanctions were lifted. The CAI’s adoption by 2022 is now highly unlikely. Whatever the CAI’s short- comings, the failure to conclude it could lead to slower progress on true reciprocity and erode public tolerance towards Chinese FDI. Current political tensions could also be exacerbated by greater EU attention to issues surrounding the South China Sea and Taiwan, as well as China’s human rights record. Experience has shown that it was the souring of political relations, rather than FDI screening, that triggered drastic falls in Chinese investment into the US. Shifting relations could similarly become a key risk for Chinese investment in Europe going forward.

No comments:

Post a Comment