Dakota Cary

Executive Summary

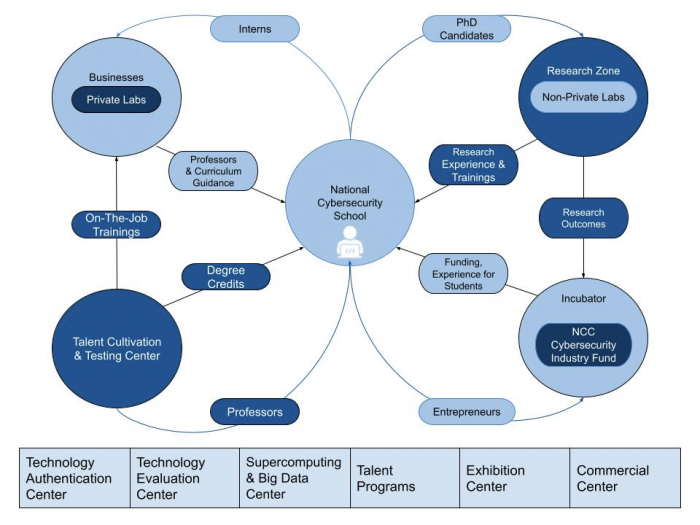

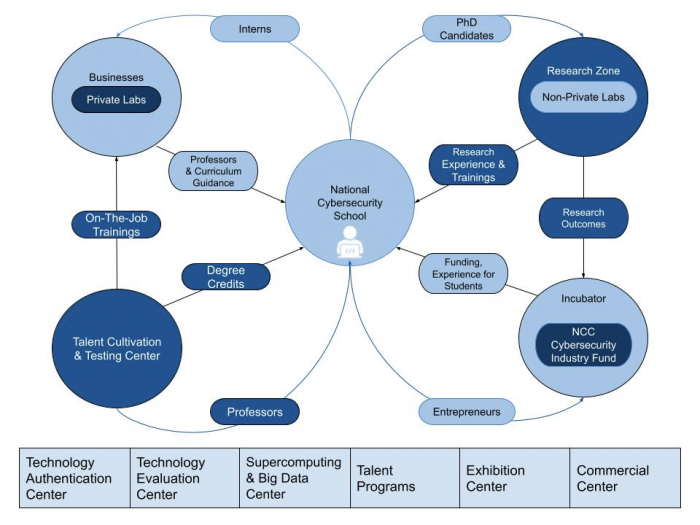

China wants to be a “cyber powerhouse” (网络强国). At the heart of this mission is the sprawling 40 km2 campus of the National Cybersecurity Center. Formally called the National Cybersecurity Talent and Innovation Base (国家网络安全人才与创新基地), the NCC is being built in Wuhan. The campus, which China began constructing in 2017 and is still building, includes seven centers for research, talent cultivation, and entrepreneurship; two government-focused laboratories; and a National Cybersecurity School. The NCC enjoys support from the highest levels of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). The Party’s Cyberspace Affairs Commission established a committee to oversee the NCC’s operations and policies, giving it a direct line to Beijing.

International competition forged China’s commitment to growing its cyber capabilities. Despite a deficit of 1.4 million cybersecurity professionals, China is already a near-peer cyber power to the United States. Still, the current shortfall leaves China’s businesses and infrastructure vulnerable to attack, while spreading thin its offensive talent. The NCC will likely bolster China’s capabilities, making competition in the cyber domain fiercer still. U.S. policymakers should expect that China’s increased capabilities will threaten the U.S. advantage in cyberspace.

China’s path to becoming a “cyber powerhouse” is not free of obstacles. Japan’s National Institute for Defense Studies identified three issues China’s military must overcome to build an effective cyber force: talent, innovation, and indigenization. These cyber-specific challenges likely extend to China’s civilian intelligence service, the Ministry of State Security, and its internal security agency, the Ministry of Public Security.

First, China’s military faces a shortage of cyber operators. The country’s deficit of 1.4 million cybersecurity professionals weighs on the military’s ability to recruit qualified candidates. In the same way a shortage of pilots would ground planes, China’s shortage of cybersecurity professionals prevents the military from operating effectively. Two of the NCC’s 10 components directly target talent cultivation. The NCC’s “leading mission” is the National Cybersecurity School, whose first class of 1,300 students will graduate in 2022. CCP policymakers hope to see 2,500 graduates each year. The length of time it will take to reach full capacity remains unclear. The Talent Cultivation and Testing Center, the second talent-focused component, offers courses and certifications for early- and mid-career cybersecurity professionals. The Talent Cultivation and Testing Center has the capacity to teach six thousand trainees each month, more than seventy thousand in a year at full capacity. Combined, both components of the NCC could train more than five hundred thousand professionals in a single decade. Even half that number would still help overcome the talent gap.

Second, China’s current system for innovation in the cyber domain will not meet its strategic goals. Chinese military strategists view cyber operations as a possible “Assassin’s Mace” (杀手)—a tool for asymmetric advantage over a superior force in military confrontation. Advanced militaries rely on interconnected networks to operate as a unified system, or “system of systems.” Chinese strategists argue that disrupting communications within these systems is key to deterring military engagement. No single tool will establish an asymmetric advantage. Instead, China must reliably produce attack types for each system targeted. There are no silver bullets, but a workforce capable of significant innovation is critical to implementing the strategy.

Three of the 10 components directly support innovation at the NCC. Students and startups can solicit business guidance and investment funds at the NCC’s Incubator. Besides supporting private-sector innovation, two other components of the NCC support government-focused research. The NCC hosts two non-private laboratories, the Combined Cybersecurity Research Institute and the Offense-Defense Lab. Both institutions likely conduct cybersecurity research for government use (see component analysis below). Other components indirectly support innovation. The NCC’s Exhibition Center, for example, hosts events that attract inventive talent from across the country. China’s Military-Civil Fusion strategy ensures that the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) can harvest new tools that come from the NCC, regardless of who develops it, which may help China develop asymmetric advantage.

Third, China aims to reduce its reliance on foreign cyber technology. The Snowden revelations reinforced PLA concerns that foreign technology facilitates espionage. Leaked documents revealed occasional close cooperation between the U.S. government and technology companies. The CCP wants indigenous replacements for foreign software to protect its military and critical infrastructure from foreign interference. Indigenization will also allow China to become more aggressive. If the PLA uses the same foreign-made software they are attacking, then their attack against that software leaves Chinese networks vulnerable to counterattack through replication. By attacking the software, they prove its vulnerability. If a capability is reciprocal, it is not asymmetric. Replacing foreign software would go a long way to remediate the Party’s concerns about foreign espionage and remove constraints on policy choices.

A local government report shows that policymakers intend to harvest indigenous innovation from the NCC. Citing important Party organs, the report states that “leaders have repeatedly made it clear that the National Cybersecurity Base must closely monitor independent innovation (主创新) of core cybersecurity technologies, promote Chinese-made independently controllable (主可控) replacement plans, and build a secure and controllable information technology system…” Local officials serve as a pipeline between the NCC’s ecosystem and the needs of the Party by targeting nascent technologies. If the NCC is successful at spurring innovation, the pipeline may ease adoption of indigenous products and facilitate the replacement of foreign technology.

The CCP has high expectations for the NCC, and policymakers and businesses are making the necessary investments to be successful. But the prospects for the NCC’s impact on China’s cyber capabilities are uneven. On talent cultivation, the NCC is surefooted. The National Cybersecurity School and Talent Cultivation and Testing Center already educates students and certifies trainees. Successive classes of NCC graduates and trainees will slowly fill the ranks of China’s state-backed hackers and private-sector defenders. The NCC’s impact on innovation will only become clear over the next decade. Key stakeholders are making investments in research and development (R&D) facilities, talent programs, and the NCC’s Incubator. But innovation is fickle. Following best practices, like concentrating talent and capital in a tightly defined area, creates a supportive environment but cannot guarantee the development of new technology. Over the long run, the NCC’s talent cultivation efforts will likely impact the dynamics of nation-state cyber competition. The tools these operators use may well be designed by NCC graduates, too. China’s competitors should be prepared to respond to these developments.

Figure 1: Concept Map for Components of the NCC

Source: CSET.

No comments:

Post a Comment