LAURA TYSON, JOHN ZYSMAN

BERKLEY – Semiconductors are an essential product. They are the foundation of everything from sophisticated weapons systems and critical infrastructure to a growing number of technologies used daily by consumers and businesses. Scarcities are thus felt widely, and the current semiconductor shortage has exposed gaps and vulnerabilities across the global supply system.

Today’s semiconductor shortage reflects a variety of factors – including significant pandemic-driven disruptions in both demand and supply and unilateral US trade restrictions with China. And any number of causes could trigger future shortages. For the sake of both national and economic security, the United States needs a multifaceted strategy for providing a competitive, resilient, secure, and sustainable (CRSS) supply of semiconductors. Such a strategy must address all parts of the industry, from design, fabrication, assembly, and packaging to materials and manufacturing equipment.

Each of these elements of the supply chain is critical. Competitive market conditions must prevail throughout the industry, because excessive market power in any one segment can jeopardize supply. The system must also be resilient to shocks like fires, droughts, earthquakes, and geopolitical tensions and upheavals. And it must be secure in two senses: the US must maintain reliable access to cutting-edge chips and the means of producing them, and chip supplies need to be protected from threats like counterfeiting, theft, cyberattacks, and espionage. Finally, the supply must be sustainable, accounting for the significant environmental and energy costs of chip production.

CRSS does not mean national autonomy in the semiconductor industry. That goal would be neither feasible nor economically rational, given the complex global supply system and the dispersion of industry knowledge, talent, and production. What CRSS does mean is that the US should cooperate closely with the European Union, Japan, Singapore, Israel, and others who form core parts of its secure supply base.

CRSS also does not mean preventing China from purchasing or selling semiconductors on global markets, or from developing its own semiconductor industry in ways that do not violate global trade and investment rules. Weaponizing trade and investment restrictions to thwart China’s long-run semiconductor ambitions will be costly and counterproductive. It will disrupt global supplies, increase semiconductor prices, exacerbate shortages, and strengthen China’s resolve to move faster to achieve autonomy.

A successful CRSS strategy does require the US and its allies to maintain a competitive edge vis-à-vis China, including through coordinated trade and investment policies to contain the mounting security threats that China poses within the semiconductor supply system.

The first step toward devising a CRSS strategy is to understand the semiconductor industry as it exists today. As a recent analysis by the Biden administration notes, although companies headquartered either in the US or in allied countries retain significant positions and leverage throughout the industry, most chip production has moved out of the US. For leading-edge chips, the US and its allies rely heavily on the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC), which has a dominant market position. For cheaper commodity chips, they increasingly rely on other producers in Taiwan, South Korea, and China.

With production so heavily concentrated in Asia, supply-chain resilience is threatened by mounting geopolitical tensions with China. A top CRSS priority therefore is to expand the competitive production capabilities of both US companies and foreign companies located in the US for both leading-edge and other chips.

Fortunately, there are already promising private-sector plans to do this. Intel, for example, has recommitted to leading-edge domestic production, and both TSMC and Samsung have announced plans to build production facilities in the US. The EU is also committed to expanding its own semiconductor production, which if successful would make the global system more competitive, resilient, and secure.

Beyond maintaining the chip supply, leading-edge foundries play a critical role in driving competition and innovation throughout the supply system. The current state of foundry production technology tells design companies what can be built now and what future capabilities they can anticipate.

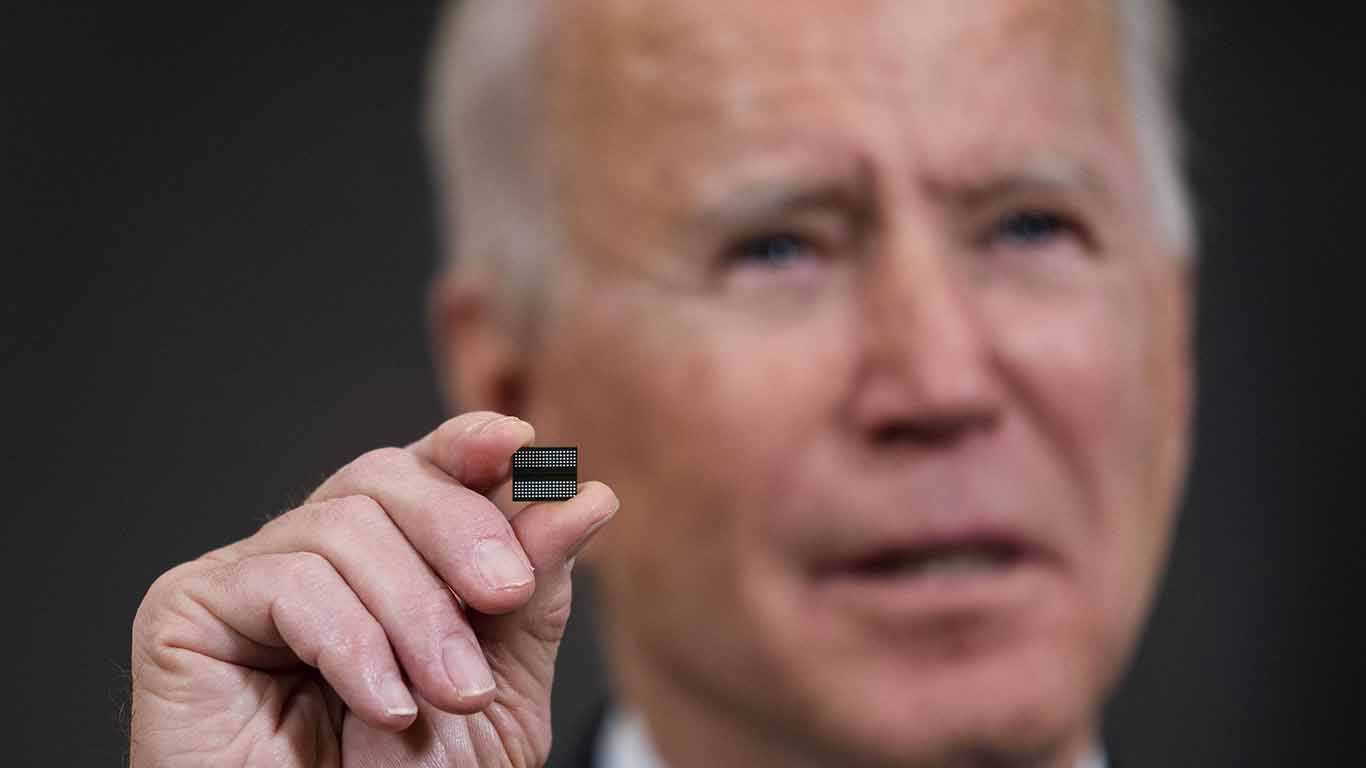

To help expand domestic production capabilities, US President Joe Biden has called for a $52 billion investment in the semiconductor industry, and the US Senate has passed a bill that includes generous refundable investment tax credits and a federal fund to match state and local fiscal incentives for investments in semiconductor production.

The effectiveness of these tools will depend on how the incentives are targeted and how the funds are allocated. There is a danger that generous fiscal support will end up subsidizing private investments that are already being planned in response to growing demand. We may find that conventional fiscal tools are not up to the task and that out-of-the-box approaches are needed. Assuring US production of chips designed and used for defense and military purposes will be a particular challenge.

Recognizing that CRSS depends on innovation in every segment of the semiconductor industry, the Biden administration and Senate plans also call for significant increases in funding for research and development. Both basic and pre-competitive research in semiconductors is an increasingly borderless process, which means that the effectiveness of US outlays will depend on cooperation with allies and participation by their companies.

Finally, it is important to note that while the US continues to lead in overall semiconductor R&D, its ability to prototype and scale innovations has been hampered by the “lab-to-fab valley of death.” Breakthrough projects that may be viable in research labs are often prohibitively expensive to demonstrate, leaving them starved of the private investment needed to achieve scale.

A promising approach to address this problem is a pre-competitive public-private R&D partnership to share equipment and other costs among participants. Perhaps a similar “commons” approach could be extended to chip production as well.

While the tactics of the policy response can be debated, the need for one is not in doubt. America’s prosperity and security depend on a comprehensive strategy for ensuring a competitive, resilient, secure, and sustainable semiconductor industry.

No comments:

Post a Comment