Douglas H. Paal

We are now six months into the new administration of President

Joe Biden, in the middle of his plans to “build back better” for the United States. But when it comes to policies related to China, there is not yet much to see that gives concrete meaning to that slogan.

Of course, we should remember that in his remarkably disciplined campaign for office, candidate Biden focused on first defeating the Covid-19 pandemic, jump-starting the American economy and dealing with social and racial inequities, not reversing or substantially changing Donald Trump’s erratic China policies.

In the early months, Biden has presided over remarkably successful

roll-outs of vaccines against the pandemic. You can feel America getting back to work, school and life as the virus loosens its grip.

Biden has legislated for aggregate huge financial relief for ordinary citizens. He has more legislative initiatives in the pipeline. And the new administration is more diverse in its composition than any predecessor’s.

But when it comes to dealing with China, the administration’s stated ambitions so far have been quite limited. Understandably, the Biden team wants to do the good work of repairing the alliances and partnerships with other capitals that Trump did so much to undermine.

This week’s foray through Europe is meant to underline that effort. The thinking appears to be that to deal with China ultimately from a position of strength, a lot of homework needs to be done first. It is difficult to fault that logic.

Meanwhile, Biden’s foreign policy team has been reinforcing many of the messages on China that were earlier sent by the Trump administration. Secretary of State Antony Blinken and National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan staged a showdown in Alaska with their Chinese counterparts, where they aired American concerns about sensitive topics such as

A presidential delegation visited Taiwan to show support in its long-running stand-off with mainland China, and new rules were issued loosening guidance on contact between Taiwanese and American officials. The Biden administration continues to refer to its adherence to the one-China policy, in hopes of avoiding provoking Beijing into an even more belligerent stance while giving greater rein to Washington’s “unofficial” dealings with Taipei.

More recently, it seems the Biden administration is trying to tighten the loose ends of competition, cooperation and contention left behind by the Trump administration.

For example, Trump issued executive orders limiting Chinese-owned apps, but did so in a haphazard fashion that was not standing up to legal challenges, so Biden issued a

new order this past week rescinding Trump’s earlier order and establishing what is likely to be a more robust legal basis for accomplishing the same objective.

Defence Secretary Lloyd Austin announced his acceptance of the recommendations – unspecified – from a task force formed to refocus the US military as a whole on threats from China and away from previous focal areas such as Iraq, Afghanistan and terrorism.

US Trade Representative Katherine Tai and Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen held their first conversations with Chinese Vice-Premier Liu He on the “Phase 1” trade agreement reached between Trump and Beijing in 2019, which is due for review. Ways forward were not disclosed and probably not discussed.

The Biden administration has not articulated how it plans to compete with China in the growing arena of multiparty trade agreements.

As all these preliminaries unfold, it is not at all clear whether Biden is heading towards something new or different in managing the major contours of the fractious and increasingly dangerous US-China relationship. Washington has yet to name its next ambassador to China, who would be expected to foreshadow Biden’s policies during confirmation hearings before the Senate.

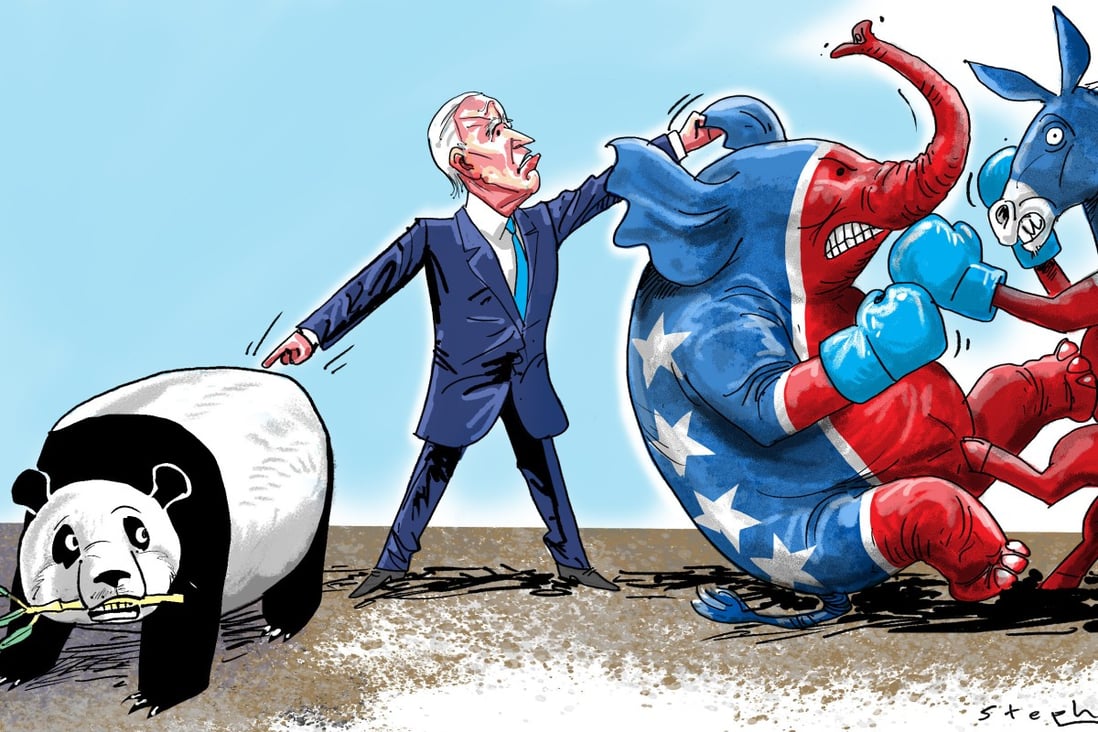

Behind this slow-motion unveiling of Biden’s China policy lies an important factor. In a capital where bipartisanship is close to non-existent, opposition to China is an important exception.

Indeed, the US Senate last week passed its version of the US Innovation and Competition Act (also known as the Endless Frontier Act) with support from both parties, dedicating

US$250 billion to competing with China.

A House version is likely to pass as well, and changes can be expected in the normal conference process between the competing bills. This, too, can be viewed as part of the effort to get stronger at home to prepare to deal more effectively with Beijing.

By keeping China policy details in the shadows, moreover, the Biden administration can continue to ride the wave of bipartisan hostility towards Beijing as it struggles in more partisan fights over taxation, infrastructure spending, international trade and the way forward on other domestic issues.

Biden’s Democratic predecessors, Bill Clinton and Barack Obama, both pushed strong domestic initiatives when they had Democratic Congressional majorities in the first two years of their terms, only to lose those majorities in the first midterm election.

It is hard to imagine that Biden and his advisers do not have preserving and enhancing Democratic majorities in the 2022 election very much in mind as they take their time getting around to how they are going to handle the very specific challenges China represents. Hostility to China is a stronger unifying political card than anything else out there today.

No comments:

Post a Comment