Itai Brun

Israel hit Hamas hard, but the Israeli public was frustrated by the ongoing rocket fire, the IDF's inability to prevent it, and the lack of a decisive and unequivocal Israeli victory. This dissonance is the outcome of three surprises experienced by the Israeli public in the course of the campaign: the fact that the political echelon chose (yet again) to deter Hamas and not to vanquish it; the inability of the IDF's offensive operations to stop the rocket fire; and the military’s difficulty in explaining and demonstrating its significant achievements. These surprises are the result of a continued failure by the political and military leadership to explain to the public both Israel’s chosen strategy and current nature of military conflicts. In advance of future confrontations, time now should be used to review and coordinate expectations with the public, clarify the rationale behind the chosen Israeli strategy, forge an effective way to explain military achievements, and openly discuss the characteristics of war in the current era.

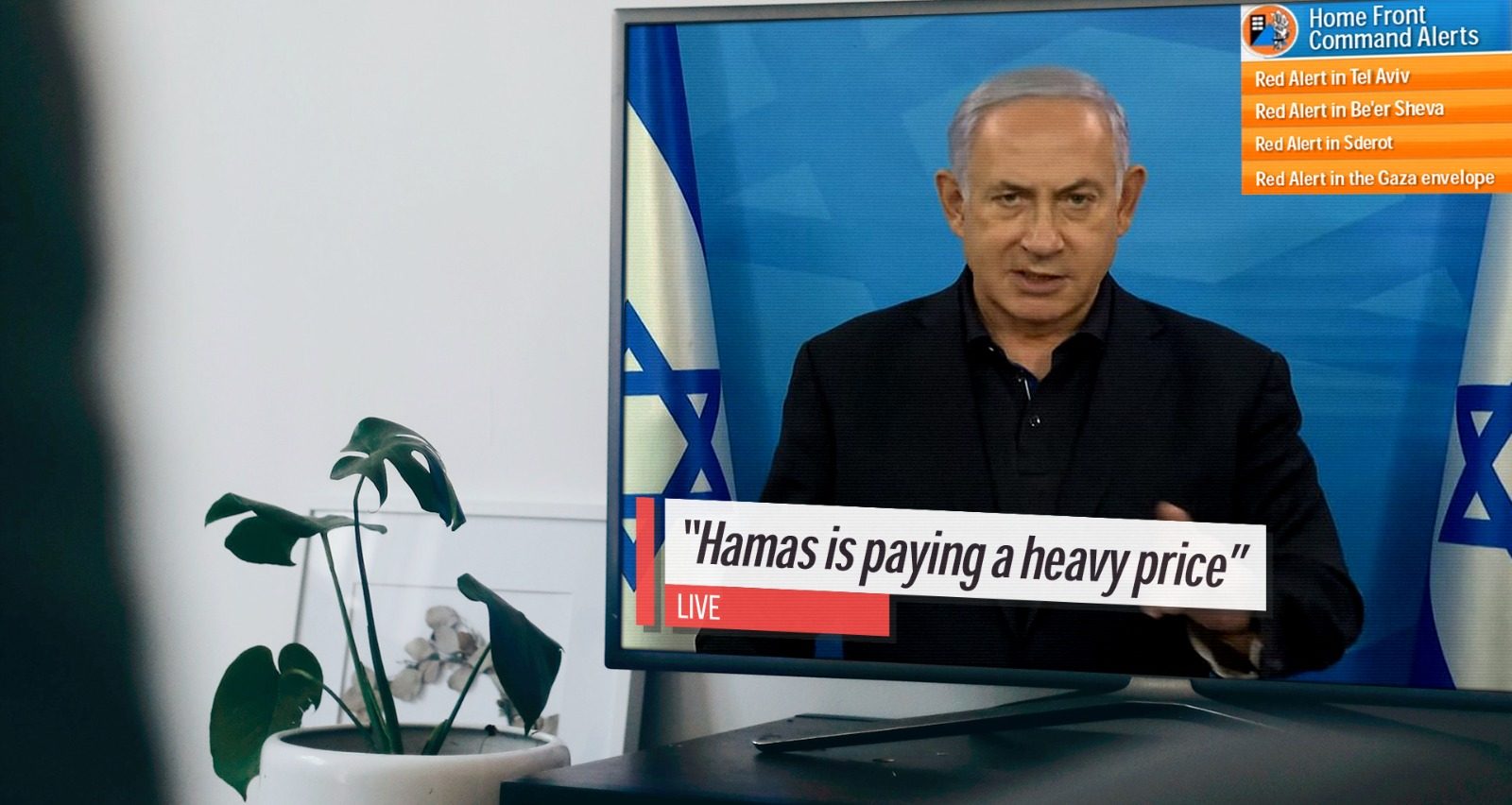

Throughout Operation Guardian of the Walls, Israel’s Prime Minister, Minister of Defense, Chief of Staff, and other senior IDF officers reiterated the massive, unprecedented damage inflicted on Hamas and estimated that by the end of the campaign it would lead to strengthened Israeli deterrence. In doing so, they conveyed strong satisfaction with how the operation was managed and the results of the IDF's offensive activity. And indeed, Hamas was hit hard, but the Israeli public was frustrated by the steady rocket fire, the IDF's inability to prevent it, and the lack of a clear and unequivocal Israeli victory. On all the media outlets, every additional rocket barrage from Gaza was perceived as a sign of the IDF's failed attack on Hamas. In the current conflict, the pace of events accelerated over that of previous conflicts, and therefore the familiar feeling of a wasted opportunity appeared earlier this time.

This frustrating dissonance is the outcome of three surprises experienced by the Israeli public during the days of the operation, as well as (some) surprises related to Hamas's activities (the very opening of the operation, the rocket fire on Jerusalem, and the heavy salvoes to the center of the country). But as is often the case, the three main surprises were about ourselves: the Israeli public discovered that its government chose (again) to deter Hamas and not to vanquish it; that the IDF's offensive activity, despite its tremendous intensity, was unable to stop the rocket fire; and that the army was hard-pressed to explain and demonstrate its achievements during the operation. The surprises stem in part from a proclivity typical of the Israeli public not to look reality entirely in the face. However, they are mainly the result of the longstanding deliberate ambiguity by the political and military leaderships, combined with their continued failure to explain to the public the Israeli strategy and current nature of military conflicts.

Thus, when the confrontation began, Israelis once again discovered the clear priority given by their political and military leadership to deterrence operations based primarily on airpower and its aversion to decisive operations that require the use of ground forces maneuvering into enemy territory. This overt preference can be identified at least since the 1990s, with Operations Accountability and Grapes of Wrath, and has remained consistent, even during the Second Lebanon War and in the operations in Gaza. This time, too, Israel chose a vague goal of "strengthening deterrence," a choice that affects the nature of the operation and especially its results. It was clear to the decision makers that there would be no clear and unequivocal ruling and no victory image. They also estimated (and rightly so) that the operation had an appropriate purpose that would be achieved at a reasonable price. But the public, which has continued to hear in recent years the rhetoric of "decision" and "victory," was disappointed and surprised.

The second surprise relates to the difficulty of dealing with Hamas rocket launches. Over the years, Hamas has equipped itself with thousands of rockets, of various ranges, hidden among the heart of Gaza’s civilian population and underground sites. This arrangement allows Hamas to launch barrages almost without interruption, to the Gaza envelope communities, the medium range (Ashdod, Beer Sheva), and the center of the country. This matter is at the heart of its concept of warfare. Israel has built an exceptionally effective active defense system (Iron Dome), which demonstrated highly impressive achievements during the operation. The IDF also undertook major offensive efforts against the launch points. But it turned out again that the IDF could not prevent the launch of the barrages as well as a limited number of deadly hits. This state of affairs cannot be substantially changed in the near future. Rocket launches therefore have strategic significance and the ability to shape cognition surrounding the campaign.

The third surprise is related to the previous two. The IDF's offensive activity indeed inflicted very significant damage on Hamas that could affect its decision making process in the future. But most of all, the current confrontation revealed the huge gap in the visibility of the achievements of both sides during the confrontation itself. Hamas's achievements – the launches, the alarms, the damage to civilian buildings, and the human casualties – are clear, immediate, and understood in the context of the current conflict. The IDF's achievements are significant, but they are cumulative and much less tangible and overt. When this gap is combined with the growing recognition of the inability to stop the rocket barrages, a dismal result is obtained: the Israeli public simply did not experience the success of the IDF. The IDF built an idea based on deterring Hamas from the next conflict, but the public wanted a victory in the current conflict.

Operation Guardian of the Walls was conducted along two different dimensions. On one dimension, Hamas attacked the Israeli home front with an unprecedented number of rockets; and on the second, Israel attacked Hamas in Gaza with force and accuracy far greater than those of previous operations. In practice, however, only a loose connection was created between the two dimensions. In view of the continued rocket salvoes, Israeli civilians under continual fire were not overly impressed by the enormous destruction that the IDF inflicted on the enemy's weapons arrays and the number of its operatives injured. The IDF did not craft an effective way to explain to the public the achievements of the offensive activity. The use of data on the numbers of attacks and targets, the number of kilometers of damaged underground infrastructure, and the vagueness surrounding the military logic of the attacks on the high-rise buildings did not help in this matter.

In this sense, it seems that the top political and military leaders were surprised during the days of the operation. They found (again) that the desire to reach a clear and unequivocal result in a brief blitzkrieg still characterizes the thinking of the Israeli public about the desired outcome of military conflicts, and is the prism through which the public views the actual results. This is one of the reasons for the sense of frustration experienced by the Israeli public, which was intensified by the media, which gave clear priority to dealing with the ongoing rocket barrages and had difficulty explaining the IDF's achievements. The (unfulfilled) expectation of a targeted thwarting of one of the well-known figures in the Hamas leadership reflects a desire for a victory image, but it is doubtful whether the success of such an operation would have changed the basic situation.

Under the current strategy advanced by the political echelon, it is doubtful whether there is a better way than the one chosen by the IDF to deal with Hamas. Lessons learned from previous conflicts also show that in operations designed to achieve deterrence, the events and sentiments during the fighting must be separated from its effects in the medium and long terms. It is therefore to be hoped that this time, too, deterrence has indeed been strengthened and will be manifested in the form of a relatively long period of quiet. If so, it is better for the political and military leadership to take the time to review and coordinate expectations with the public, to underscore the basic logic of its strategy, and to openly discuss the nature of the future conflicts. All of this should happen before the coming war with Hezbollah, which will, of course, be much more problematic.

No comments:

Post a Comment