By Steve Blank

We just finished our 6th annual Hacking for Defense class at Stanford.

What a year. With the pandemic winding down, it finally feels like the beginning of the end.

This was my sixth time teaching a virtual class during the lockdown – and for our students, likely their 15th or more. Hacking for Defense has teams of students working to understand and solve national security problems. Although the class was run completely online, and even though they were suffering from Zoom fatigue, the 10 teams of 42 students collectively interviewed 1142 beneficiaries, stakeholders, requirements writers, program managers, industry partners, etc. - while simultaneously building a series of minimal viable products.

At the end of the quarter, each team gave a final "Lessons Learned" presentation. Unlike traditional demo days or Shark Tanks, which are, "Here’s how smart I am, and isn’t this a great product, please give me money,” a Lessons Learned presentation tells the story of a team’s 10-week journey and hard-won learning and discovery. For all of them, it's a roller coaster narrative describing what happens when you discover that everything you thought you knew on day one was wrong and how they eventually got it right.

Here’s how they did it and what they delivered.

How Do You Get Out of the Building When You Can't Get Out of the Building?

This class is built on conducting in-person interviews with customers, beneficiaries and stakeholders, but due to the pandemic, teams now had to do all their customer discovery via a computer screen. This would seem to be a fatal stake through the heart of the class. How would customer interviews work via video? After teaching remotely for the last year, we’ve learned that customer discovery is actually more efficient using video conferencing. It increased the number of interviews the students were able to do each week.

Most of the people the students needed to talk to were sheltering at home, which meant gatekeepers didn't surround them. While the students missed gaining the context of standing on a navy ship or visiting a drone control station, or watching someone try their app or hardware, the teaching team’s assessment was that remote interviews were more than an adequate substitute. When Covid restrictions are over, we plan to add remote customer discovery to the students’ toolkit. (See here for an extended discussion of remote customer discovery.)

We Changed The Class Format

While teaching remotely, we made two major changes to the class. Previously, each of the teams presented a weekly ten-minute summary consisting of “here’s what we thought, here’s what we did, here’s what we found, here’s what we’re going to do next week.” While we kept that cadence, it was too exhausting for all the other teams to stare at their screen watching every other team present. So we split the weekly student presentations into thirds – three teams presented to the entire class, then three teams each went into two Zoom breakout rooms. During the quarter, we rotated the teams and instructors through the main room and breakout sessions.

The second change was the addition of alumni guest speakers – students who had taken the class in the past. They offered insights about what they got right and wrong and what they wished they had known.

Lessons Learned Presentation Format

For the final Lessons Learned presentation, each of the eight teams presented a 2-minute video to provide context about their problem. This was followed by an 8-minute slide presentation describing their customer discovery journey over the 10 weeks. While all the teams used the Mission Model Canvas (videos here), Customer Development, and Agile Engineering to build Minimal Viable Products, each of their journeys was unique.

By the end of the class, all the teams realized that the problem as given by the sponsor had morphed into something bigger, deeper and much more interesting.

All the presentations are worth a watch.

Team Fleetwise – Vehicle Fleet Management

Mission-Driven Entrepreneurship

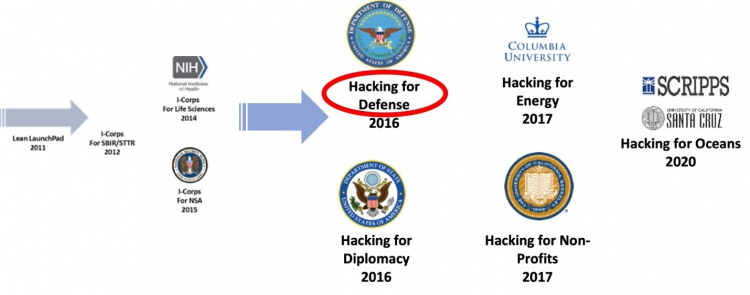

This class is part of a bigger idea – Mission-Driven Entrepreneurship. Instead of students or faculty coming in with their own ideas, we ask them to work on societal problems, whether they’re problems for the State Department or the Department of Defense or non-profits/NGOs or the Oceans and Climate or for anything the students are passionate about. The trick is we use the same Lean LaunchPad / I-Corps curriculum — and the same class structure – experiential, hands-on-- driven this time by a mission model, not a business model. (The National Science Foundation, National Security Agency, and the Common Mission Project have helped promote the expansion of the methodology worldwide.)

Mission-driven entrepreneurship is the answer to students who say, "I want to give back. I want to make my community, country, or world a better place while being challenged to solve some of the toughest problems.”

Project Agrippa – Logistics and Sustainment in Indo-Pacific

It Started With An Idea

Hacking for Defense has its origins in the Lean LaunchPad class I first taught at Stanford in 2011. I observed that teaching case studies and how to write a business plan as a capstone entrepreneurship class didn't match the hands-on chaos of a startup. Furthermore, there was no entrepreneurship class that combined experiential learning with the Lean methodology. Our goal was to teach both theory and practice.

The same year we started the class, it was adopted by the National Science Foundation to train Principal Investigators who wanted to get a federal grant for commercializing their science (an SBIR grant). The NSF observed, “The class is the scientific method for entrepreneurship. Scientists understand hypothesis testing” and relabeled the class as the NSF I-Corps (Innovation Corps). The class is now taught in 9 regional locations supporting 98 universities and has trained over 1500 science teams. It was adopted by the National Institutes of Health as I-Corps at NIH in 2014 and at the National Security Agency in 2015.

Team Silknet – Detecting Ground Base Threats

Origins Of Hacking For Defense

In 2016, brainstorming with Pete Newell of BMNT and Joe Felter at Stanford, we observed that students in our research universities had little connection to the problems their government was trying to solve or the larger issues civil society was grappling with. As we thought about how we could get students engaged, we realized the same Lean LaunchPad/I-Corps class would provide a framework to do so. That year we launched both Hacking for Defense and Hacking for Diplomacy (with Professor Jeremy Weinstein and the State Department) at Stanford.

Team Flexible Fingerprints – Improve Cybersecurity

Goals for the Hacking for Defense Class

Our primary goal was to teach students Lean Innovation while they engaged in national public service. Today if college students want to give back to their country, they think of Teach for America, the Peace Corps, or AmeriCorps, or perhaps the U.S. Digital Service or the GSA’s 18F. Few consider opportunities to make the world safer with the Department of Defense, Intelligence community, or other government agencies.

In the class, we saw that students could learn about the nation’s threats and security challenges while working with innovators inside the DoD and Intelligence Community. At the same time, the experience would introduce to the sponsors, who are innovators inside the Department of Defense (DOD) and Intelligence Community (IC), a methodology that could help them understand and better respond to rapidly evolving threats. We wanted to show that if we could get teams to rapidly discover the real problems in the field using Lean methods, and only then articulate the requirements to solve them, defense acquisition programs could operate at speed and urgency and deliver timely and needed solutions.

Finally, we wanted to familiarize students with the military as a profession and help them better understand its expertise and its proper role in society. We hoped it would also show our sponsors in the Department of Defense and Intelligence community that civilian students can make a meaningful contribution to problem understanding and rapid prototyping of solutions to real-world problems.

Mission-Driven In 50 Universities And Continuing To Expand In Scope And Reach

What started as a class is now a movement.

From its beginning with our Stanford class, Hacking for Defense is now offered in over 50 universities in the U.S., as well as in the U.K. and Australia. Steve Weinstein started Hacking for Impact (Non-Profits) and Hacking for Local (Oakland) at UC Berkeley and Hacking for Oceans at both Scripps and UC Santa Cruz. Hacking for Homeland Security was launched last year at the Colorado School of Mines and Carnegie Mellon University. A version for NASA is coming up next.

And to help businesses recover from the pandemic, the teaching team taught a series of Hacking For Recovery classes last summer.

Our Hacking for Defense team continues to look for opportunities to adapt and apply the course methodology for broader impact and public good. Project Agrippa, for example, piloted a new “Hacking for Strategy” initiative inspired by their experience in Stanford’s “Technology, Innovation and Modern War” class that Raj Shah, Joe Felter and I taught last fall. This all-star team of 4 undergraduates and a JD/MBA developed new ways to provide logistical support to maritime forces in the Indo-Pacific region. Their recommendations drew on insights gleaned from over 242! interviews (a national H4D class record). After in-person briefings to Marine Corps and Navy commanders and staff across major commands from California to Hawaii, they received interest in establishing a future collaboration, validating our hypothesis that Hacking for Strategy would be a welcome addition to our course offerings. Its premise is that keeping America safe requires us to maintain a technological edge and use cutting-edge technology to develop new operational concepts and strategies. Stay tuned.

Team AngelComms – Rescuing Downed Pilots

Team Salus – Patching Operational Systems to Keep them Secure

Team Mongoose – Tracking Hackers’ Disposable Infrastructure

Team Engage – Preparing Aviators to Make Critical High-Stakes Decisions

What's Next For These Teams?

When they graduate, the Stanford students on these teams have the pick of jobs in startups, companies, and consulting firms. Most are applying to H4X Labs, an accelerator focused on building dual-use companies that sell to both the government and commercial firms. Many will continue to work with their problem sponsor. Several will join the new Stanford Gordian Knot Center, which is focused on the intersection of policy, operational concepts, and technology.

In our post-class survey, 86% of the students said that the class had an impact on their immediate next steps in their career. Over 75% said it changed their opinion of working with the Department of Defense and other USG organizations.

It Takes A Village

While I authored this blog post, this class is a team project. The secret sauce of the success of Hacking for Defense at Stanford is the extraordinary group of dedicated volunteers supporting our students in so many critical ways.

The teaching team consisted of myself and:

Pete Newell, retired Army Colonel and ex Director of the Army’s Rapid Equipping Force, now CEO of BMNT.

Joe Felter, retired Army Colonel; former deputy assistant secretary of defense for South Asia, Southeast Asia, and Oceania; and William J. Perry Fellow at Stanford’s Center for International Security and Cooperation.

Steve Weinstein, 30-year veteran of Silicon Valley technology companies and Hollywood media companies. Steve was CEO of MovieLabs, the joint R&D lab of all the major motion picture studios. He runs H4X Labs.

Tom Bedecarré, the founder and CEO of AKQA, the leading digital advertising agency.

Jeff Decker, a Stanford researcher focusing on dual-use research. Jeff served in the U.S. Army as a special operations light infantry squad leader in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Our teaching assistants this year were Nick Mirda; Sally Eagen; Joel Johnson, a past graduate of Hacking for Defense; and Valeria Rincon. A special thanks to the National Security Innovation Network (NSIN) and Rich Carlin and the Office of Naval Research for supporting the program at Stanford and across the country, as well Lockheed Martin and Northrop Grumman. And our course advisor, Tom Byers, Professor of Engineering and Faculty Director, STVP.

We were lucky to get a team of mentors (VCs and entrepreneurs) as well as an extraordinary force of military liaisons from the Hoover Institution's National Security Affairs Fellows program, Stanford senior military fellowship program, and other accomplished military affiliated volunteers. This diverse group of experienced experts selflessly volunteer their time to help coach the teams. Thanks to Todd Basche, Rafi Holtzman, Kevin Ray, Craig Seidel, Katie Tobin, Jennifer Quarrie, Jason Chen, Richard Tippitt, Rich Lawson, Commander Jack Sounders, Mike Hoeschele, Donnie Hasseltine, Steve Skipper, LTC Jim Wiese, Col. Denny Davis, Commander Jeff Vanak, Marco Romani, Rachel Costello, LtCol Kenny Del Mazo, Don Peppers, Mark Wilson and LTC Ed Cuevas

And of course a big shout-out to our problem sponsors: MSgt Ashley McCarthy, Jason Stack, Col Sean Heidgerken, LTC Richard Barnes, George Huber, Neal Ziring, Shane Williams, Anthony Ries, Russell Hoffing, Javier Garcia, Matt Correa, Shawn Walsh, and Claudia Quigley.

No comments:

Post a Comment