By Daniel Davis

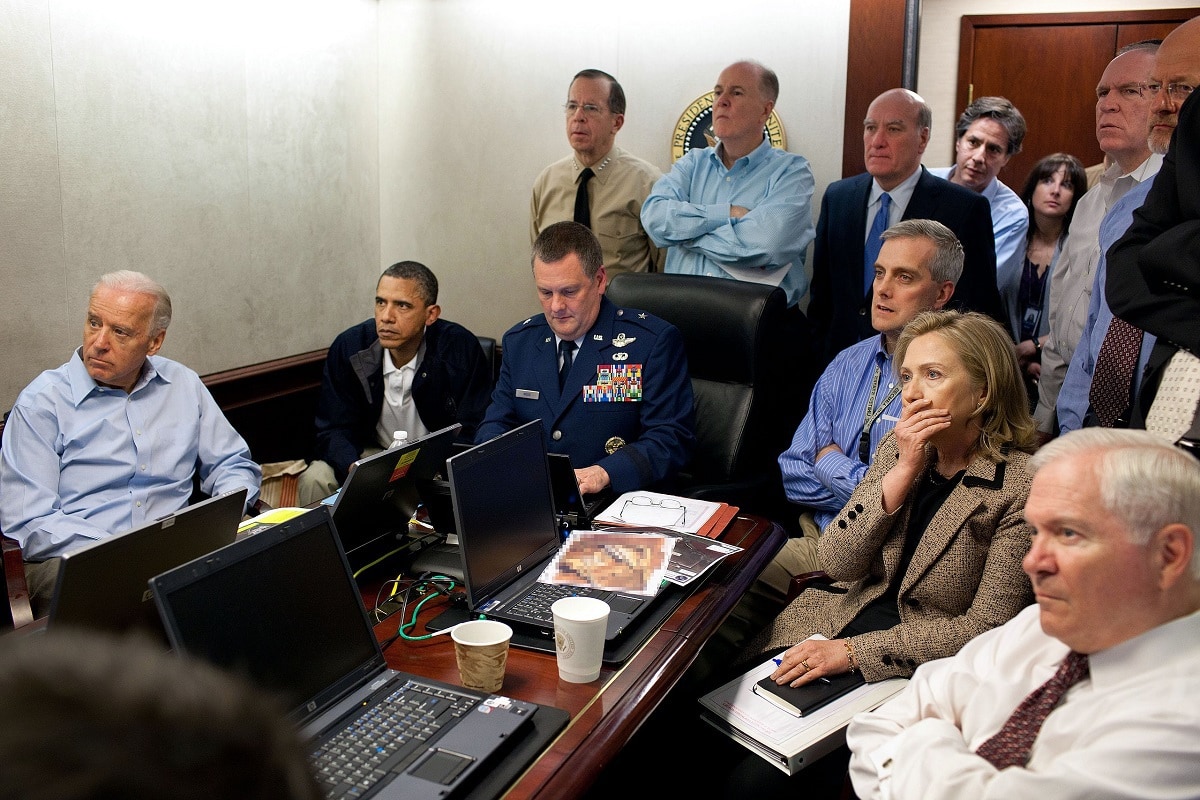

President Barack Obama and Vice President Joe Biden, along with with members of the national security team, receive an update on the mission against Osama bin Laden in the Situation Room of the White House, May 1, 2011. Please note: a classified document seen in this photograph has been obscured. (Official White House Photo by Pete Souza)..This official White House photograph is being made available only for publication by news organizations and/or for personal use printing by the subject(s) of the photograph. The photograph may not be manipulated in any way and may not be used in commercial or political materials, advertisements, emails, products, promotions that in any way suggests approval or endorsement of the President, the First Family, or the White House.

How fast time passes: Exactly 10 years ago on Sunday, President Barack Obama somberly addressed the nation to announce that Osama Bin Laden had been killed by U.S. Forces in Pakistan.

The terrorist’s death “marks the most significant achievement to date” in America’s quest to defeat al-Qaeda, Obama said. But a decade later, and almost 20 years since the 9/11 attacks, it is now clear that the killing had little more than symbolic meaning – and illustrates the importance of setting realistic objectives in the establishment of foreign policy.

President George W. Bush had tried for over seven years to hunt down and kill or capture the terror leader. When Obama finally succeeded, Bush congratulated him and said Bin Laden’s killing was a “momentous” accomplishment that marked “a victory for America.”

And yet, it marked nothing of the kind.

On the contrary, it had virtually no impact on either our strategic fight against al-Qaeda or on the tactical battles we were waging against violent extremists in numerous countries around the globe.

Why This Was No Game Changer Moment: My Experience on the Battlefield

I was deployed to Afghanistan as a liaison officer in 2005, to Iraq as a military trainer in 2009, and as the Army Rapid Equipping Force team chief to Afghanistan in 2010-11. I traveled literally thousands of miles throughout Iraq and Afghanistan on various types of counterinsurgency missions and throughout my entire career deployed in combat operations abroad, saw the same dynamic at play, whether at the tactical, operational, or strategic level: whenever a terrorist was killed or captured, he would be replaced.

Sometimes the replacement would take weeks, other times it would occur within days. On some occasions, the replacement would be of less capacity than the man he replaced, but there were other cases where the new fighter was even better than the one he replaced. But in virtually every case, there was no meaningful impact on the battlefield: so long as the insurgent group is committed to the fight, they will never wont for bodies to replace the fallen.

What Research Tells Us

A 2020 New York Times analysis of the Taliban way of fighting captured the spirit of the insurgent mindset. When trying to explain why the Taliban would continue fighting after tens of thousands of their coreligionists had been killed over the previous two decades, one fighter explained that “we see this fight as worship.” If a “brother is killed,” he continued, the next Taliban fighter will “step into the brother’s shoes” and the fight would continue.

In a 2015 analysis, the Washington Post reported that there were upwards of 20,000 Islamic madrassas in Pakistan alone. Between 10 percent and 15 percent of them are believed to be affiliated with extremist or violent groups. No matter how many insurgents the U.S. or NATO would kill, therefore, there would never be insufficient numbers of new recruits to replace them. That is one of the most fundamental reason the war was never militarily winnable for the United States. That shouldn’t have been a surprise to us.

Throughout the 10-year Soviet-Afghan war, the USSR always held a dramatic advantage over the mujahadeen fighters in technology, training, and killing power. The Soviets suffered a total of 15,000 troops killed while the Afghan people suffered approximately 1.5 million killed. No matter how many people the Soviets killed, more would always show up to the next battle. In the two decades of the U.S. war in Afghanistan the raw numbers were smaller but the ratios remarkably similar: 2,400 Americans killed, and 157,000 Afghans were killed.

One of the best traits of American culture is that we like to win and will spare almost no effort in an attempt to achieve victory; its also one of our worst traits. Barely a week after 9/11, Bush addressed the nation at a Joint Session of Congress and announced a “war on terror.” Problem is, “terror” is a tactic, not an enemy. Even when the mission was refined two years later and renamed “the global war on terrorism (GWOT),” the objectives given the Armed Forces were never militarily attainable.

In 2006 the Chairman for the Joint Chiefs of Staff issued the National Military Strategic Plan for the War on Terrorism. The document detailed several objectives in its mission to win the GWOT. Key among these were:

a requirement to attack to disrupt terrorist networks “so as to cause the enemies to be incapable or unwilling to attack the U.S.,”

deny terrorist networks the possession or use of weapons of mass destruction,

establish conditions “that allow partner nations to govern their territory effectively,” and to

contribute to the establishment of a global environment “inhospitable to violent extre3mists and all who support them.”

The problem with them all: the tasks were so vague as to be effectively impossible to define, much less accomplish. The list represented a set of policy aspirations and not a list of militarily achievable objectives.

The Reality

The ramifications of this ambiguity were demonstrated with Bush changed the military mission for Afghanistan in 2007 to outright nation-building, when Obama used military force on Libya in 2011, sent troops to Iraq and Iraq in 2015 and 2016, and when Trump refused to withdraw troops from Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan even though there were few if any American security interests at stake. Three presidents spent trillions of dollars, over two decades, killing thousands of enemy fighters, not only failed to make us safer, it actually made the security environment less stable.

It was emotionally satisfying for many Americans when Osama Bin Laden was killed in 2011; none shed a tear over his demise. But the best way to ensure the security of our country is not in fighting endless and unnecessary battles, but in fighting only when necessary – and even then only when there are militarily achievable tasks whose attainment can result in a safer America.

Daniel L. Davis is a former Lt. Col. in the U.S. Army who deployed into combat zones four times. He is the author of “The Eleventh Hour in 2020 America.” Follow him @DanielLDavis1. The views in the article do not represent the opinions of any other organization.

No comments:

Post a Comment