By SYDNEY J. FREEDBERG JR.

WASHINGTON: What comes after the M1 Abrams, the Army’s massive Reagan-era main battle tank? “Everything is on the table at this point,” the service’s armor modernization director, Maj. Gen. Richard Ross Coffman, says. He didn’t give many details so I asked experts to speculate.

To my surprise, everyone we talked to, from retired Army tankers and industry experts to drone-loving futurists, agreed that manned armored vehicles of some kind will still have a place in future wars. Why? Human soldiers will still need a way to move about the battlefield under armor protection, and they’ll need it even – or especially – when killer drones swarm the skies. After all, it’s far easier for the enemy to build a drone that can kill an exposed human than one that can penetrate an armored vehicle.

Textron M5 Ripsaw unmanned mini-tank

Beyond that baseline, there was little consensus. Some of our sources felt that further upgrades to the M1 Abrams would suffice for the foreseeable future, arguing there’s not – yet – been any radical change in tactics or fundamental improvement in armored vehicle design that would call for an all-new vehicle. Others saw potential for a new kind of tank. And some thought the M1’s replacement shouldn’t be a new tank at all, but a whole family of different vehicles, manned and unmanned, working together as a networked wolfpack.

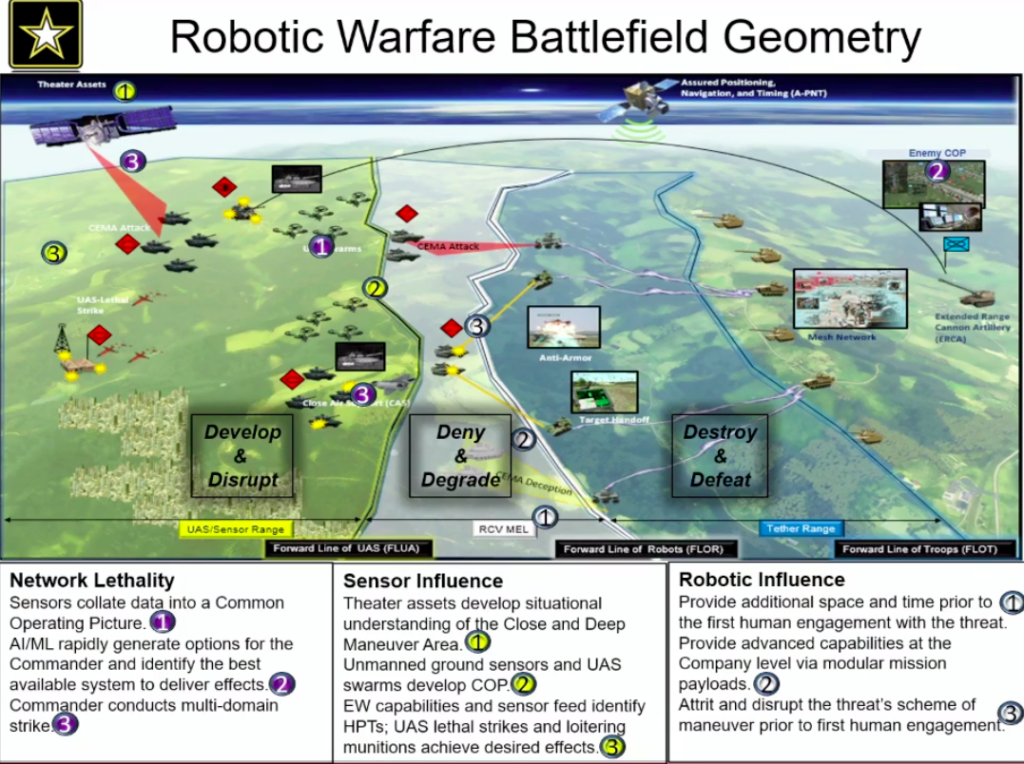

That concept of “manned-unmanned teaming” is already being explored by the Army’s Robotic Combat Vehicle program. It’s also central to the Air Force’s Loyal Wingman drones and the Navy’s unmanned “Ghost Fleet,” designed to support manned fighters and warships respectively.

There’s revolutionary potential here to disaggregate traditional weapons platforms. Instead of having gun, sensors, and crew all on one vehicle, you could put, say, your long-range sensors on a drone, your decoys on another (expendable) drone, your main gun on a ground robot, and your human controller in a small, well-armored command vehicle hidden some distance away.

“I would expect to see the bundled capabilities of the M1 gradually broken apart – the requirements and functions of the M1 being spread over multiple systems,” said Dan Patt, a former DARPA official now with thinktank CSBA. “Crewed armored vehicles will be with us for quite some time, [but] the bigger military impact comes from the ability to split apart weapon system functions, take more risks, and experiment with different force combinations in adaptable ways. These changes are ready now.”

Of course, this revolution depends on the network technologies actually working to keep all those humans and robots connected – even in the face of enemy hacking and jamming.

Mock-up of the Israeli-made IAI Harop (Harpy) “suicide drone” used by Azerbaijani forces against Armenia in Nagorno-Karabakh

The Drones Of Nagorno-Karabakh

As for the individual armored vehicles, whatever they look like, their survival will increasingly depend on their defenses against enemy drones. That was the bloody lesson of both Russia’s 2014 invasion of Ukraine, in which scout drones pinpointed Ukrainian armored vehicles for devastating rocket barrages, and Azerbaijan’s 2020 offensive in Nagorno-Karabakh, in which armed and kamikaze drones decimated Armenian armor.

How big a change does this portend? Based on the bloody lessons taught Ukraine and Armenia, “I think we’re likely to see technology radically transform the ground warfare environment over the next several decades in ways not seen since World War I,” said Paul Scharre, a former Army Ranger who’s now vice president of the thinktank CNAS. “The persistence and accessibility of drones renders the contemporary – and future – battlefield much more transparent to aerial surveillance and, consequently, attack.”

But there are promising countermeasures already available today, argued Samuel Bendett, an expert on the Russian military at CNA.

“Had the Armenians prepared their tanks for the new type of war that took place last October, their losses would have been far fewer,” he told me. “Much of what we saw in the Nagorno-Karabakh involved older Soviet tanks in the Armenian service that were not well defended against loitering munitions, [which] actually do not pack a big punch.”

By contrast, modern Russian tanks routinely carry reactive armor tiles, which preemptively detonate in the path of incoming warheads; infrared dazzlers, which blind the sensors of anti-tank guided missiles; and active-protection systems, which physically shoot down inbound munitions like a miniaturized missile defense. The US finally began installing an active protection system – the Israeli Trophy – on its Abrams tanks in 2018.

Even without new technology, better tactics can make a difference, argued Thomas Spoehr, a retired Army three-star now at Heritage.

“Right now, UAS with smart munitions and kamikaze drones do seem to command the upper hand. But nothing lasts forever,” Spoehr told me. “Regaining freedom of maneuver for tanks might come more from changes in tactics versus technology.”

A historical parallel is how new man-portable anti-tank missiles savaged Israeli armor in the 1973 war, only to have the Israelis learn to flush the missile teams out with infantry. Likewise, the seemingly unstoppable threat of drones could be countered by new tactics aimed at their weak points, for example intensive jamming of their control links and sensors.

Nothing will make the tank invulnerable to drones – but it’s crucial to remember that tanks have never been invulnerable on any battlefield, popular mythmaking aside. Even in the early days during World War I, German artillerymen quickly learned that the new Allied tanks could be destroyed by existing field guns.

In fact, tanks have never even been the toughest target on the battlefield. (There’s actually a Marine Corps saying, “hunting tanks is fun and easy.”) Historically the hardest thing to kill has been deeply dug-in infantry, from the entrenched defenders of the Western Front to the Viet Cong in their tunnels. But trenches and tunnels are stationary, and once infantry gets out of cover and tries to move, it’s horrifically vulnerable to machinegun and artillery fire.

An early British Mark IV tank knocked out near Gaza in 1917.

So the tank was invented in 1916 to restore mobility to the battlefield. Its armor protection allowed it to advance under fire. Its tracks allowed it to cross trenches and other obstacles. Its guns allowed it to destroy enemy weapons that threatened its advance. The primitive tanks of World War I failed to break the deadlock of the trenches, not due to any fault in their armor or weapons, but because their engines proved too unreliable to sustain prolonged advances.

Ever since the blitzkrieg of World War II, however, tanks have been essential tools of battlefield mobility. Even in urban and jungle combat, tanks’ ability to smash through walls and trees while surviving improvised mines allows them to clear paths for the infantry.

Will tanks still be essential and decisive in future wars? Or will they be mere adjuncts to some other, newer weapons system like the swarming drone?

M1 Abrams tanks of the 1st Cavalry Division fire during a NATO Atlantic Resolve exercise in Latvia.

Command Vehicles Or Combat Vehicles?

Even Scharre, the most futuristic-minded expert we spoke to for this story, doesn’t see armored vehicles disappearing entirely. He just doesn’t see them as being the decisive weapon anymore, but a supporting arm.

“I suspect that tanks will not go away completely,” he told me, “but they are likely to go the way of the infantry — as a mopping up force for close-in engagements, rather than the central role tanks have played in ground combat since World War II.”

That central role will shift to ground robots, drones, and long-range missiles, Scharre believes, with the decisive clash often occurring before the humans on opposing sides ever lay eyes on one another. But armored vehicles will still be valuable, especially when humans have to survive maneuvering through a war zone.

“Soldiers will be needed on the battlefield to command-and-control the fight and secure terrain, and they will need to be in armored vehicles to remain protected,” Scharre said. “But the role of armored vehicles is likely to shift, over time, to predominantly command-and-control platforms for a distributed network of air and ground sensors, drones, and robotic platforms.”

Patt, the ex-DARPA official, agreed. “The best replacement for the M1 is likely a customizable multi-domain force package,” he said, combining ground robots, aerial drones, and a manned vehicle “that can pull intel from space when needed, seamlessly call in backup fires, coordinate its own beyond-line-of-sight targeting, and rely on automation in targeting and navigation to multiply the effectiveness of the human crew.” Note that directly engaging targets with a 120mm cannon isn’t on that list.

The Army envisions drones and ground robots advancing ahead of humans in future wars. (Enemy forces are at the left of the chart, friendly forces are moving right to left).

Other experts saw the value both of robot swarms and of something resembling a traditional main battle tank, with a human crew, heavy armor, and big gun to engage the enemy’s toughest targets within line of sight.

“I see the need to diversify our holdings in [armor] to hedge against technology,” said Spoehr. “I think the replacement for the Abrams is not a single vehicle, but several platforms.”

“Some still look like tanks for direct force engagements, when the threat from UAVs is low or technology has found a better, more reliable counter-UAV solution,” he said. “Other, lightly armored manned platforms launch aerial drones and suicide missiles. Still others are fully autonomous platforms controlled by other manned, heavily protected platforms.”

Tactically, Spoehr said, such a force would operate in three waves: first the drones to take out enemy air defenses and command posts, then ground robots, then finally manned main battle tanks to take out the toughest targets.

But why put a human in your heavy tank? Because, bluntly, remote control remains awkward and autonomous robots remain stupid. Sometimes you need an experienced human in the vehicle, onboard. That way they can use all their senses to understand the situation – the smell of smoke, the sound of the guns, the vibration of the engine — instead of staring at a screen. That way, too, their input can’t be hacked, jammed, or otherwise disconnected.

Other functions can be automated in the near future, but not the ability to command a tank in combat, Bendett told me. “This is not something that can be replaced by a neural network or an advanced algorithm anytime soon, given that no one can truly replicate all the nuances of a tank commander’s experience that may span many years, and even decades.”

“The future replacement for an M1 should be a family of vehicles, [including] a manned, well defended tank … which in turn commands a team of mid-sized, heavily defended UGVs [Unmanned Ground Vehicles] for ISR and combat roles, [plus] drones,” he added. “If the UGVs are unable to accomplish their task for some reason, it would be up to a manned tank with a commander who has extensive experience.”

US Army M1 Abrams tank with Trophy Active Protection Systems (APS) and improved protection for machinegun operator.

Upgrade The M1 Or Replace It?

If a manned main battle tank remains necessary, can the M1 Abrams continue to fill that role, or does the Army need a new MBT?

The M1 Abrams could be the centerpiece of the future manned-unmanned armored force, said Bendett. Much as it’s been upgraded in the past multiple times since its introduction in 1980, it just needs to be upgraded again, with counter-drone defenses, electronic warfare, and a command system for the robots.

Lt. Gen. (retired) Guy Swan, vice-president for education at AUSA.

But there are only so many upgrades the old M1 can take, argued Guy Swan, a retired armor officer now with the Association of the US Army.

“One thing is for sure, we cannot continue to hang more on the M1 Abrams frame,” Swan told me. “The tank, while I believe it’s still the best in the world, is far too heavy to navigate regions of the world where ground forces may have to operate.”

“The future tank can and will indeed be less than 60 tons – a threshold for many roads and bridges – without losing crew protection,” he said, thanks to new active and passive protections. That must include sophisticated “masking” both of its visual appearance and of its infrared and radio-frequency emissions, he said, because in a world of drones, “traditional camouflage is not enough.”

A clean-slate tank design would allow for a new engine, Swan added, preferably a hybrid-electric one that puts less strain on supply lines than the M1’s gas-guzzling turbine. It would also allow for an improved turret, although Swan felt the existing 120mm cannon has plenty of potential with upgraded targeting systems and ammunition.

Others felt more firepower was needed for future wars. “55 to 65 tons, [with] a bigger gun or laser, on-board loitering munitions, [an] unmanned turret, [and] hybrid engine,” wrote one retired officer.

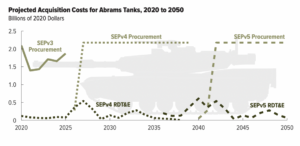

CBO projections for future spending on M1 Abrams tanks. SOURCE: Congressional Budget Office

Other sources were more skeptical of new technology – and of the Army’s ability to exploit it. “They are totally unwilling to accept what is doable in anticipation of some magic solution that never seems to become reality,” said one retired industry expert.“[So] they lose momentum and support — and then move on to the next shiny object.”

If you don’t trust the Army to manage a major program, then an upgraded M1 Abrams is the best you can expect. A recent Congressional Budget Office study projected Army spending on armored vehicles through 2050 and predicted that Abrams upgrades would eat a lion’s share of it. “CBO projects that more than 40 percent of the total costs would be for upgrading and remanufacturing Abrams tanks,” the study said, an average of $2 billion a year.

No comments:

Post a Comment