By SYDNEY J. FREEDBERG JR

Gen. John “Mike” Murray (left) with former Army Secretary Ryan McCarthy

WASHINGTON: The US must relearn the lessons of Cold War-era containment in order to compete strategically with China, the head of Army Futures Command told us. That means everything from better coordination among US government agencies — both military and civilian — to a robust deterrence based on forward-positioned forces.

In recent years, Army Cyber Command has been improving its information warfare capabilities so it’s not out-tweeted and outmaneuvered by online propagandists for China, Russia, ISIS, and other adversaries. The Army also has a long history of boosting friends and deterring adversaries with advisors, training missions and exercises. Those are both aspects of what’s variously called “information warfare,” “political warfare,” or “great power competition.”

The new HQ for Army Cyber Command, Fortitude Hall on Fort Gordon, Ga.

But the Army can’t solve this huge problem on its own, Gen. Mike Murray told me and BD’s Theresa Hitchens in an exclusive interview. (Click here for Part I and here for Part II). The whole US military isn’t enough: Civilian agencies have to act effectively too.

“This is not something that the Army can do. It’s not something the joint forces or the DoD can do on its own,” Murray said. “The competition has to be a whole-of-government effort.”

“The Chinese see competition as a whole of government effort, a whole of party effort,” he noted, “and I think they’re actually pretty good at it.”

Consider how authoritarians in Beijing are able to coordinate cyber espionage, propaganda, economic sticks and carrots, and multiple military and paramilitary forces. In the South China Sea alone, there’s the PLA Navy, Chinese Coast Guard, and the ostensibly civilian fishing boats of the “maritime militia.” Such a “whole of government” effort is something US agencies have struggled to put together for years, at least since the Cold War effort to contain the Soviet Union.

“If you go back to the Cold War era, we saw competition much differently,” Murray said. “We called it containment, but it was called competition with the Soviet Union. It’s just we’re way out of practice.”

Vladimir Lenin pores over the newspaper in his Kremlin office. Contemporary Russian and Chinese political warfare has its roots in Lenin’s strategy of the 1920s.

Now, the Chinese threat is admittedly very different from the Soviet Union. Revolutionary Communism had a global, idealistic appeal that Chinese state capitalism can’t match. But the Chinese economy is far stronger a competitor to the US – and far more able to sway neutrals to its side – than the USSR’s state-planned system ever was. And the US and China are far more intertwined today, by trade and the Internet and immigration, than the Soviet Union ever was with the capitalist world.

As the Army Chief of Staff puts it in a recent strategy paper: “One of the significant differences between current great power competition and the Cold War [is that] today, even some of the United States’ closest, most long-standing allies have significant relations with adversaries.”

But the fundamental logic of great power competition is universal, the Army argues. For example, positioning military forces forward – either in permanent bases or on temporary deployments — doesn’t just deter aggression by adversaries, it also builds relationships with friends and neutrals. That’s something the Army is heavily invested in, with specialized advisor brigades already competing with the Chinese in Africa, and extensive training programs both in the US and abroad.

“I want to be able to identify what [the threat] is, I want to be able to attribute it to whomever is the adversary that’s taken that shot, as an example, and then, I’ve got to be able to share that information,” says Maj. Gen. Leah Lauderback, who heads the ISR Directorate.

“A lot of people miss this: If you’re forward, it enables you to build relationships,” Murray said. Back stateside, the Army has “officers from other nations attending military schooling… from all over INDOPACOM region: [Again], you begin to build relationships. And relationships are going to matter in the future in terms of access and influence… That’s a piece of competition.”

While these “soft power” aspects of competition are important, Murray emphasized that the military hard power to deter aggression is non-negotiable.

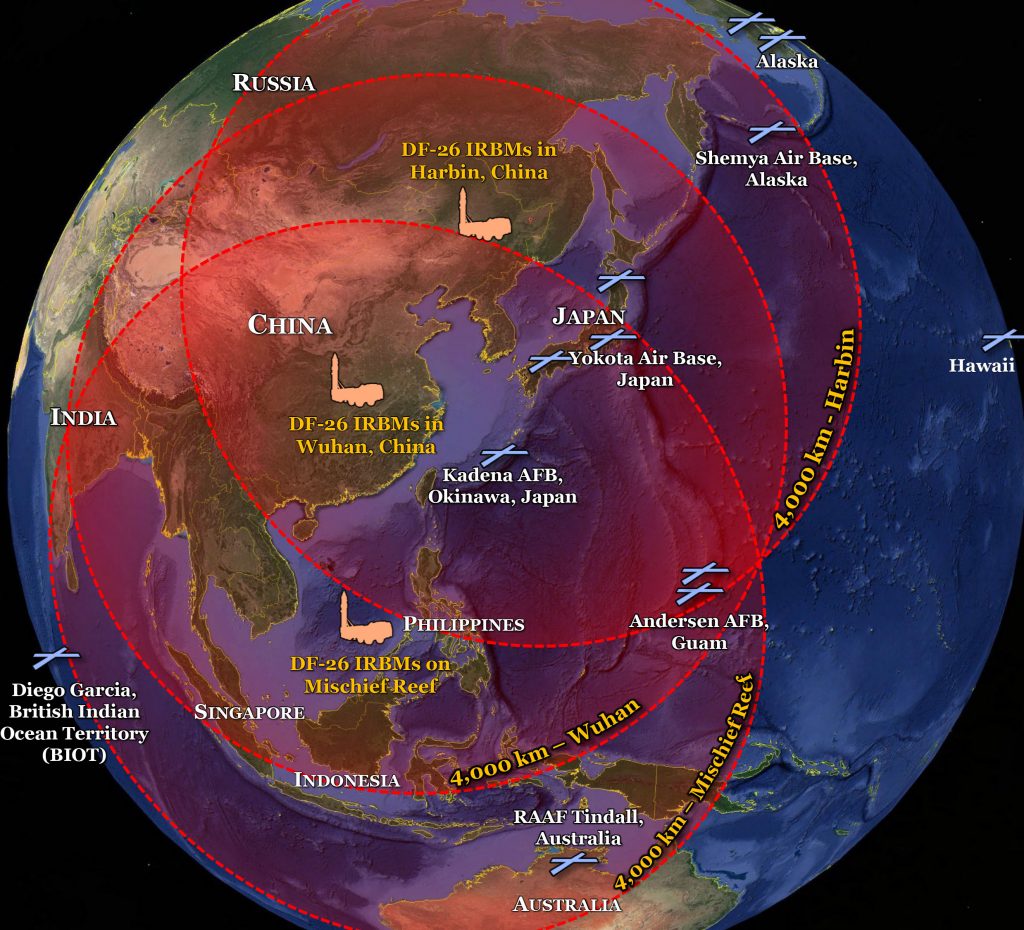

Ranges of Chinese land-based missiles. (CSBA graphic; click to expand)

What China has set up in the Western Pacific – and Russia in Eastern Europe, and Iran in the Gulf – is a layered defense of long-range sensors, precision missiles and other systems known in the trade as anti-access/area denial (A2/AD). The intent, as the name implies, is to keep US forces from intervening in a given region, giving the adversary free rein to bully its neighbors.

To deter such aggression, the US armed services are seeking ways to break down these A2/AD defenses. Even the Army, which historically relied on other services’ air- and sea-power to clear its path, is developing long-range missiles to help air-power break in – although where it’d base them in the Western Pacific is still unclear.

“How can we help the joint force penetrate that defense?” Murray said. “It’s not that you establish domain dominance over the entire area of operations all at once. But how can you take out pieces of it, achieve localized domain dominance, that the join force could exploit?”

Wherever a shooting war begins, however, it’s unlikely to stay localized, Murray and other generals warn.

“We look at this too narrowly,” Murray said. The Chinese Communist Party took power promising to deliver an end to the insecurity, corruption and national weakness of the “century of humiliation” from 1839 to 1949. A defeat by the United States would dangerously undermine the regime’s legitimacy.

Chinese President Xi Jinping inspects PLA troops

“What do you think the Chinese Communist Party, specifically President Xi, fears most?” Murray said. “It’s loss of power…. They won’t go to war with us unless they’re pretty sure they can win, because a loss would lead to, if not the loss of control for the Chinese Communist Party, it’d definitely end Xi’s regime.”

If Beijing does decide a war is worth the risk, then they will do everything in their power not to lose that war, Murray argued. “If the thing you fear most, if you’re at war, is loss of that war, why would you keep the Chinese army on the sidelines and why would you only confront us in the South China Sea in the Taiwan Straits?” he said. “I think we’d be challenged in a lot of different places – the Arctic, South America, Africa – because if you don’t do that, you allow us to concentrate [our forces].”

The best way to avoid this escalation is to avoid war in the first place, and that requires a strong US force to raise the risks of aggression too high for the adversary to bear. Or, as Murray put it: “That’s why we want to have an effective deterrence: to convince whoever it is, ‘not today — today’s not the day to take this step.’”

No comments:

Post a Comment