Bobby Ghosh

By happy coincidence, my weekend shopping list included a new jar of salt: I needed rather more than a pinch to season the news of the 25-year “comprehensive strategic partnership” between Iran and China. The deal, announced with triumph in Tehran, was received with alarm in some quarters West, where it was interpreted variously as an act of Iranian defiance of U.S. sanctions and a sign that China is supplanting American influence in the Middle East.

In reality, it’s none of the above. For all the Iranian hype, the deal is not so much a “partnership” as a promissory note espousing better economic, political and trade relations between the two countries over the next quarter-century.

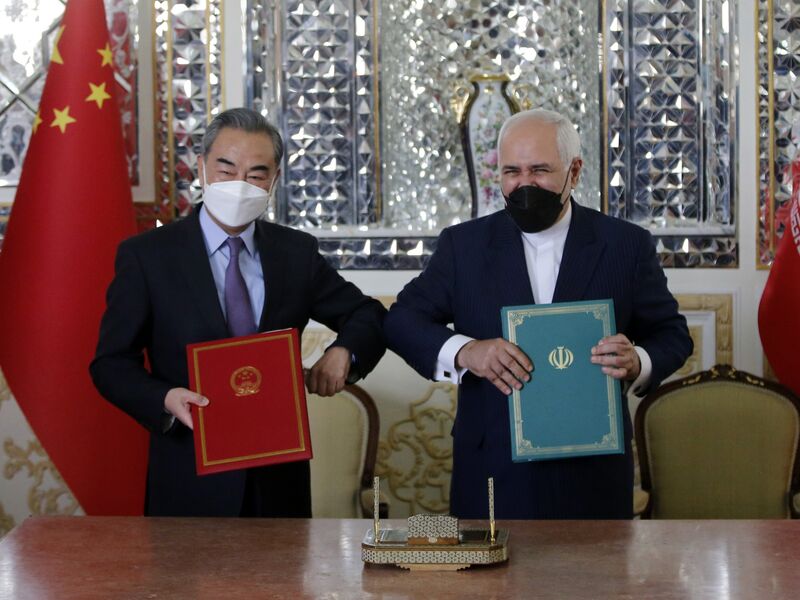

The optics of the announcement were in themselves a tell. China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi signed the formal papers on the Tehran leg of his six-nation tour of the Middle East. That suggests the deal carries less weight in Beijing than agreements with, say, Bangladesh: When President Xi Jinping wants to signal his interest in deepening Chinese influence somewhere, he puts his own signature on the paperwork.

Then, there’s the agreement itself, which is long on possibilities but short on specifics. China will invest in Iran, and in turn Iran will supply China with cheap oil. Neither side has released any information that carries dollar signs; an Iranian draft of the deal leaked last summer was so vague it led to speculation that Beijing was committing to investing anywhere from $400 billion to $800 billion, in sectors ranging from banking and infrastructure to health care and information technology.

But all this is pie-in-the-sky so long as Iran remains under the many economic sanctions imposed by President Donald Trump, not one of which has, as yet, been relaxed by his successor. President Joe Biden is keen to reverse Trump’s unilateral abrogation of the 2015 nuclear deal that Iran signed with the world powers, but Tehran has rejected all of his conditions for an American return to the agreement. (China, one of the original signatories to the nuclear agreement, has demanded that the U.S. return to the deal without any conditions.)

It is conceivable that Biden will loosen some shackles on the Iranian economy as an inducement for a resumption of nuclear talks. But most sanctions will likely stay in place while negotiations drag on; many restraints, imposed on grounds of Iran’s support for terrorism, will remain even if the two sides agree on nuclear questions.

It’s worth remembering that even after sanctions were lifted in 2015, foreign investors didn’t exactly rush into Iran, in part because of confusion over the restrictions that remained in force. The picture is, if anything, even murkier now because of the so-called “poison pills” the Trump administration inserted into the sanctions regime to prevent quick relaxation.

For Beijing, there are also geopolitical factors to consider. Xi is undoubtedly keen to acquire more influence in the Middle East: The region is critical to securing his country’s long-term supplies of hydrocarbons and to his ambition of creating a modern Silk Road. But China has been a cautious investor, focusing on a few big-ticket deals with state-owned entities.

Partnering with Iran exposes Beijing to the vagaries of regional enmities. So long as the Islamic Republic and the Arab states remain at daggers drawn, the Chinese must weigh investment opportunities in Iran against the anger they may provoke on the other side of the Persian Gulf.

And finally, there’s the matter of Iranian domestic politics, which are growing more heated in the run-up to this summer’s general elections. An agreement with the lame-duck administration of President Hassan Rouhani may not be worth very much more than the paper it is written on, especially if it confirms suspicions that Iran has forfeited its national interests in exchange for Chinese consideration.

There might yet be a run on salt in Tehran.

No comments:

Post a Comment