European officials are still reeling after Beijing had to gall to impose sanctions on several EU parliamentarians, officials, and entities this week, in response to what were relatively paltry sanctions the EU itself had imposed on a handful of Chinese functionaries involved in the persecution and mass internment of Uighurs in Xinjiang province.

European officials are still reeling after Beijing had to gall to impose sanctions on several EU parliamentarians, officials, and entities this week, in response to what were relatively paltry sanctions the EU itself had imposed on a handful of Chinese functionaries involved in the persecution and mass internment of Uighurs in Xinjiang province.German Foreign Minister Heiko Maas even appeared a little discombobulated by the whole experience, unable to reason what exactly had just happened. “We sanction people who violate human rights, not parliamentarians, as has now been done by the Chinese side. This is neither comprehensible nor acceptable for us,” he said on Monday.

Perhaps Maas had skipped over his morning newspapers for the past 12 months, but China’s response is very compatible with its new way of foreign policy: punishing anyone who dares critique the Chinese Communist Party’s methods. All you need to know can be found in a short statement issued this week by foreign ministry spokesperson Hua Chunying after China sanctioned British officials, too. “For a lengthy period of time, the United States, the United Kingdom and others have felt free to say whatever they like without allowing others to do the same,” Hua said. Those days are over and the West will “have to gradually get used to it.”

Beijing’s Number 1 Obsession

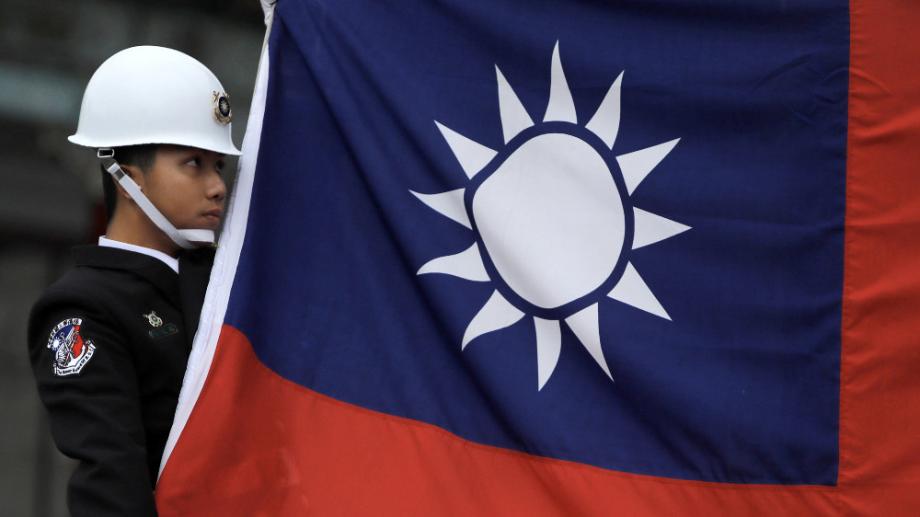

This is a serious escalation of tensions. It has to be remembered, though, that all of this is over the brutal repression in Xinjiang, which the United States calls a “genocide” while the EU does not. And Xinjiang isn’t the issue Beijing is most prickly over. That would be Taiwan, Beijing’s “number 1” obsession for decades. If the EU has generated so much aggro over Xinjiang—and is considered such an easy target that Beijing thought it worth the risk of sanctioning its representatives—how will Brussels cope when the conversation moves onto Taiwan, which it will?

Reinhard Bütikofer, a German MEP and one of the EU politicians sanctioned by China this week, noted in a tweet that Beijing’s new sanctions means he cannot travel to mainland China, but that doesn’t stop him going to Taiwan—a suggestion, perhaps, that the EU’s China hawks will now use the issue of sanctions to move the conversation onto Taiwan. And why not? That is the natural curve. If the EU wants to have a “values-led” foreign policy, Taiwan has to be a talking point. Here is a democratic vision of China, a country respected for its liberalism and, since 2020, for its competently-led government that has shown the world how to handle a pandemic.

The closest Europe got to starting a conversation about Taiwan came last August when the president of the Czech Republic’s senate, Milos Vystrcil (who belongs to a party in opposition to the government) paid a visit to Taipei to underscore the “values-based” foreign policy of the Czech political establishment. China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi, on a visit to Germany at the time, called it an “open provocation” and threatened: “We will make [Vystrcil] pay a heavy price for his short-sighted behavior and political opportunism.” This prompted even the German Foreign Minister Maas to come to Vystrcil’s defense, decrying the Chinese official for telling a European politician where he can or cannot travel to.

But after that episode the Taiwan question was swiftly swept back under the carpet. Debate could have arisen when the first EU-Taiwan investment forum was held last September but did not. Perhaps the most glaring example of how Europeans do not even want to talk about Taiwan came in September 2020, when Germany published its Indo-Pacific “guidelines.” There was a good deal of optimism that the EU’s kingmaker would finally reveal something about EU thinking on Taiwan, especially since many analysts predict the EU’s own Indo-Pacific strategy, which it promises to release soon, will be based upon the German one.

However, Germany’s strategy did not even mention Taiwan and barely mentioned potential conflict relating to the Taiwan Strait. “How can Germany contribute to peace and security without taking a stand against Xi Jinping's threat to annex Taiwan by military means?” Andreas Fulda, author of The Struggle for Democracy in Mainland China, Taiwan and Hong Kong: Sharp Power and Its Discontents, asked in an article last September. Going out on a limb, I’d say we should expect the EU’s Indo-Pacific strategy to also overlook the Taiwan question entirely.

Intolerable Ambiguity

It is true that America’s stance on Taiwan is ambiguous. After Richard Nixon’s rapprochement with China in 1973, Taiwan was booted out of the United Nations, with the Chinese seat going to Beijing. US President Jimmy Carter then abrogated the 1954 mutual defense treaty with Taiwan. But US-Taiwan relations were thrown a lifeline by the 1979 Taiwan Relations Act, passed by Congress and binding Washington to the position that “any effort to determine the future of Taiwan by other than peaceful means, including by boycotts or embargoes, [constitutes] a threat to the peace and security of the Western Pacific area and of grave concern to the United States.” Writing in his Bloomberg column, the historian Niall Ferguson noted that, for Beijing, this “ambiguity—whereby the US does not recognize Taiwan as an independent state but at the same time underwrites its security and de facto autonomy—remains an intolerable state of affairs.”

The EU’s own stance on Taiwan, though, is so ambiguous it barely exists. In 2016, the EU committed itself to using “every available channel to encourage initiatives aimed at promoting dialogue, cooperation, and confidence-building between the two sides of the Taiwan Strait.” Really? When the European Commission and Beijing agreed terms on their CAI investment pact back in December, it certainly did not tie it to peace in the Taiwan Strait.

High Risks

To make matters worse, the EU’s policy (or lack of it) over Taiwan is deaf to the experts who are now warning that conflict over the island is closer than we think, and it engages in wishful thinking by not even planning for the eventuality of conflict. The real danger is that the EU is unprepared to know even its own stance should the EU’s political conversation indeed move onto Taiwan. If that happens, the fury from Beijing will be many magnitudes worse than its reaction this week to sanctions over Xinjiang.

As one recent article noted, more than 80 Chinese military aircraft entered Taiwan’s air defense identification zone in January, compared with 41 in November and 32 in December. The Council on Foreign Relations for the first time ranked conflict between China and the United States over Taiwan as a “tier-one” risk in this year’s CFR Preventive Priorities survey. Admiral Philip Davidson, the outgoing commander of the US Indo-Pacific Command, had previously suggested that conflict over Taiwan could break out within six years. His nominated successor, Admiral John Aquilino, told a Senate armed services committee last week that it may be much sooner. “My opinion is that this problem is much closer to us than most think and we have to take this on,” he said.

The Council on Foreign Relations’ Robert Blackwill and Philip Zelikow suggested in a major study published last month that the United States and its allies, chiefly Japan, should rehearse a “plan to challenge any Chinese denial of international access to Taiwan and prepare, including with pre-positioned US supplies, including war reserve stocks, shipments of vitally needed supplies to help Taiwan defend itself.” The US and its allies should also “visibly plan to react to the attack on their forces by breaking all financial relations with China, freezing or seizing Chinese assets.” Needless to say, there is no such planning by the EU.

Granted, any sign the Europeans or Americans are building up military support for Taiwan would panic Beijing, likely exacerbating tensions. And open statements by the EU in support of Taiwanese independence would elicit angry rebukes. Yet, more so for the EU than the US, the window of opportunity for action is shutting tight. Niall Ferguson speculated that a Taiwan Crisis could be the downfall of US global power. He warned that “the US commitment to Taiwan has grown verbally stronger even as it has become militarily weaker.” And he added that “losing—or not even fighting for—Taiwan would be seen all over Asia as the end of American predominance in the region we now call the ‘Indo-Pacific.’ It would confirm the long-standing hypothesis of China’s return to primacy in Asia after two centuries of eclipse and ‘humiliation’.”

Europe’s Loss

American failure would be shared by the EU, even if Brussels keeps away from the potential conflict. Any ambition by the West of forming an alliance of Asian democracies would be over. Japan and South Korea would shuffle into non-alignment. The Southeast Asian states, whom the EU is trying to woo, would swing frantically toward China, weakening the EU’s influence on economies and climate change in the region. US failure over Taiwan would also have implications in the EU’s backyard. If the United States fails to support Taiwan, Washington will lose all credibility in defending its allies. “This could in turn send the message to Moscow that the United States wouldn’t get involved militarily in the event of, say, a conflict in the Baltics,” reads a report by the Atlantic Council published this week.

Foreign policy chief Josep Borrell claiming the EU “has the option of becoming a player, a true geostrategic actor” may elicit wry smiles these days. Imagine, though, what would happen if it is left helpless as a Taiwan Crisis erupts. Therefore, as in the COVID-19 pandemic, the EU’s new mantra should be: prepare for the worst. Unfortunately, there does not seem to be much time left.

David Hutt is a political journalist based between the Czech Republic and the United Kingdom, covering European foreign affairs and Europe-Asia relations.

No comments:

Post a Comment